October 18, 2024

Capture the (red) flag: An inside look into China’s hacking contest ecosystem

Table of contents

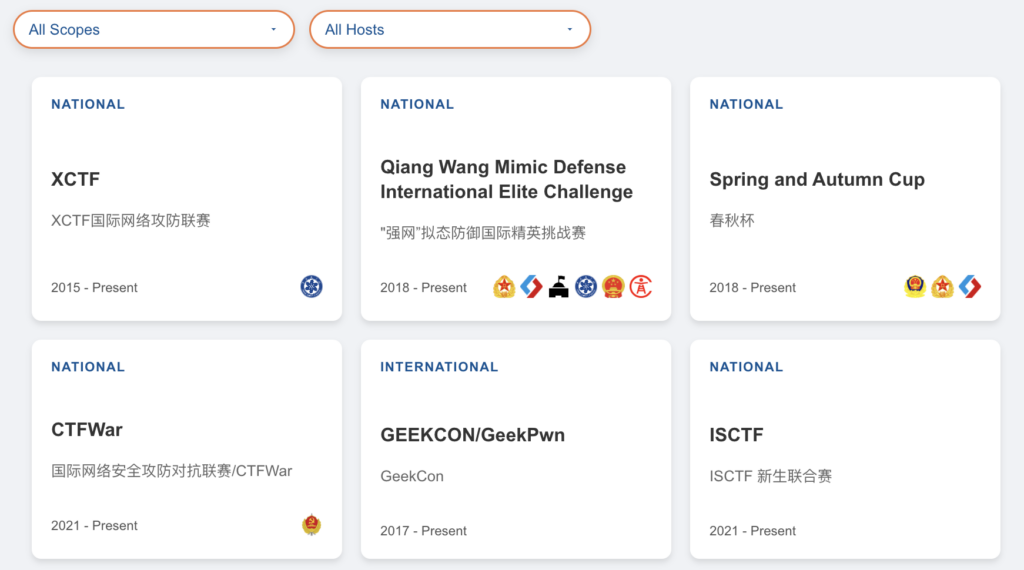

The China CTF competition tracker

The China CTF Competition Tracker presents data on 54 annually recurring hacking competitions in China. Each placard includes competition names in English and Mandarin, as well as logos of government sponsors of the competition. Users can click on each placard to reveal average number of annual participants, years of operations, hosts in both English and Mandarin, and links to competition write-ups from participants.

Executive summary

China has built the world’s most comprehensive ecosystem for capture-the-flag (CTF) competitions—the predominant form of hacking competitions, which range from team-versus-team play to Jeopardy-style knowledge challenges.

Our report finds that, pursuant to a government policy issued in 2018, many of China’s government ministries host recurring CTFs. These ministries support a handful of smaller competitions, especially through provincial or municipal governments, and one or two marquee national competitions each. These sponsoring government organs include the Ministry of Education, Cyberspace Administration of China, Chinese Academy of Science, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of State Security, and People’s Liberation Army. Over the past three years, China has hosted between forty-five and fifty-six competitions each year. In total, we identified 129 unique competitions since 2004, fifty-four of which have recurred at least once annually. Annual competition attendance can range from many hundreds to tens of thousands. The largest single-year attendance observed for the Ministry of Public Security’s Wangding Cup—which includes both companies and college students—exceeded thirty-five thousand participants.

The result of this widespread government support is an ecosystem that includes multiple national-level collegiate and professional hacking competitions. China’s CTF ecosystem is unparalleled in size and scope—something akin to four overlapping National Collegiate Athletic Associations, each with their own primary government sponsor, just for cybersecurity students to exercise their skills. We find evidence that many government-sponsored marquee competitions include talent-spotting mechanisms for recruitment.

Established practitioners also flourish in this ecosystem. Many of China’s best cybersecurity companies either host their own competitions or participate in the nationwide XCTF League. Elsewhere, foreigners are both brought into China or sought out abroad. Our report details a US college student visiting China to participate in Real World CTF who received a pitch from Chinese intelligence. On the other side of the coin, GeekCon is a private-sector competition from China that is hosted abroad and builds community with foreign hackers.

China’s CTF ecosystem should inspire policymakers outside China, but outright imitation should be avoided. Having so many national competitions in one country is wasteful. Still, Western countries should ensure the robustness of their CTF ecosystems. Each country will need to study its own systems to determine its goals, efficacy, and reach.

Introduction

Boxers do not train by reading books. Instead of in a library, they are found floating around the ring, throwing punches into bags, dodging their coach’s padded hands, and repeating their moves for hundreds of hours—all for a fight that lasts up to thirty-six minutes. Training in the ring is crucial for a fighter.

That same exposure to hands-on practice, in addition to classroom learning, is critical for cyber operators. While a degree from a prestigious institution can help someone land an interview at a tech company, companies screen candidates via coding interviews to check for actual, demonstrable capabilities. In cybersecurity, hacking competitions often serve this same role—letting students and experts prove their abilities in a safe, legal environment.

China has built the world’s most comprehensive ecosystem for CTF competitions. Hacking competitions build community, showcase talent, stimulate innovation, and allow participants to get hands-on experience.

Competitions help build communities and social bonds between hackers. In China, sector-specific competitions, like those for healthcare or public security bureaus, encourage coordination between participants in the same industry and their regulators. The social connections that result from these competitions can help participants coordinate quickly across organizations. Business in the same sector, such as hospitals, might see similar threats arise in close succession. Lessons learned by one hospital can be implemented in others if sharing mechanisms exist. Informal mechanisms, such as social relationships, allow information to spread quickly. The same is true for offensive teams—hackers struggling to hit a certain target might find a friend with access to the right tools to complete the job.

These competitions help the government spot talent for both regulatory and standard-setting roles, such as those under the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), or for offensive and defensive missions, such as those under the Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of State Security, and People’s Liberation Army. Some CTF winners receive admission to national talent programs; others are entered into a national database for cybersecurity talent. Many participants take home small sums of money. China also has a robust private-sector CTF ecosystem with a few national-level competitions that attract thousands of participants and support industry. Many of the competitions we cover in the “notable competitions” section of this paper have explicit talent spotting, recruitment, or talent programs in place.

Competitions also spur innovation. In some cases, this innovation can include new technologies. China’s Qiang Wang Elite Cyber Mimic Defense Competition helps the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) develop cyber mimic defense techniques. Participants come from industry, academia, and abroad to showcase their approaches to the PLA and its Purple Mountain Laboratory. Other forms of innovation are more subtle. When hackers exploit software, they do not all use the same strategy or tactics. A great hacker might take one step to achieve their objective, while an average hacker might take three steps. Once someone sees that great hacker’s attack path, their more efficient approach can be replicated by others. This transfer of knowledge is less glamorous and well-paid than zero-day (0day) vulnerability demonstrations but is just as impactful. China’s robust CTF ecosystem ensures that many participants learn from one another.

The hands-on experience from competitions is irreplaceable. Academia can use CTFs to check that students are not only grasping concepts in the classroom but are also ready to implement their education in the workplace. Students can use the opportunity to identify their own strengths and weaknesses, practice lackluster skills, and spot more capable classmates who can help them learn. Practitioners can keep their skills fresh on a variety of topics, even when their job only asks them to focus on a small subset of their capabilities.

This report aims to introduce and examine key components of China’s hacking contest ecosystem. To achieve this, we analyzed more than 120 China-based hacking contests since 2004, which we made available to the public. We display key information regarding more than fifty unique, recurring CTFs in our visualization, which you can access via this footnote. Key findings (see below) include the number of annual participants, total instances of participation, and most frequent competition hosts and cyber range providers in China. By integrating these data with an examination of relevant policy, key milestones within China’s hacking community, and the analysis of selected contests, we offer a comprehensive understanding of the evolution and strategic value of these events.

We anticipate that this analysis will be most useful to policymakers who are seeking to compare their countries’ promotion and use of hacking competitions to China’s system. This analysis should be considered in light of other efforts to improve cybersecurity education and job preparation.

CTF competitions

CTF competitions are simulated cybersecurity challenges and are divided into two main types: Jeopardy and Attack-Defense. Jeopardy CTFs challenge teams with tasks such as reverse engineering, web security, binary exploitation, and cryptography. Teams earn points by solving challenges and “capturing the flag,” a piece of data hidden throughout multiple challenges that proves a successful hack.

Attack-Defense CTFs involve teams attacking each other’s systems while defending their own. These systems are often virtual machines with pre-built toolkits, software, and flags provided by the hosts. Each team receives the same setup. To score points, teams must identify vulnerabilities, develop exploits, and capture opponents’ flags.

CTFs are hosted in cyber ranges, i.e., virtual environments simulating real-world networks, which provide a safe and legal space for participants to compete.

Exploit competitions focus on finding and exploiting 0day vulnerabilities. In contrast, CTF vulnerability-mining contests typically involve known vulnerabilities (n-days) in controlled environments. These competitions involving known vulnerabilities provide two benefits. First, participants exercise their exploitation capabilities in crafting code to take advantage of the vulnerability. Second, participants and organizers can learn new attack paths available against the targeted software. This knowledge provides enduring value to hackers who can replicate the same strategy in future attacks.

Background: China’s hacking competition policy

In 2014, President Xi Jinping pledged to transform China into a “cyber powerhouse.” Between 2015 and 2021, China took significant steps to improve its cybersecurity talent development and recruiting pipelines. The Ministry of Education revamped cybersecurity degree curricula, began building a National Cybersecurity Talent and Innovation Base in Wuhan, designated some universities as World-Class Cybersecurity Schools for their excellence in cybersecurity education, and identified the cybersecurity sector as an area for development in key policy documents. The US National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) inspired many of China’s efforts. In 2017, the China Information Technology Security Evaluation Center (CNITSEC, also called the MSS 13th Bureau) even selectively translated and republished a NICE report on cybersecurity competitions and their impact on workforce development.And while the United States also hosts many cybersecurity competitions for students and the public, China has excelled at this.

China set about creating its ecosystem in 2018 during its most intense period of cybersecurity talent policy reform. The Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission (CAC) and Ministry of Public Security (MPS) issued the Notice on Regulating the Promotion of Cybersecurity Competitions. The document serves as the country’s guiding policy for cybersecurity events from exploit competitions to CTFs. The authors reiterated the need for hackers to apply to the MPS to travel abroad for competitions, criticized some players’ “profit-seeking” behavior, and required vulnerabilities be disclosed to “public security and other relevant departments.” The last part is especially notable, as the policy to collect vulnerabilities at domestic competitions preceded the 2021 Regulations on the Management of Software Vulnerabilities, which mandated collection from industry. The notice also explicitly banned “the use of high-value prizes to attract participants,” a policy ignored by China’s most important exploit competitions, such as the Tianfu Cup. For all that the notice banned, the most impactful clause was its last, which encouraged relevant ministries for cybersecurity, education, information technology, and public security to promote cybersecurity competitions.

Today in China, hacking competitions have become essential components of cybersecurity capability development, aligning with key policy frameworks and serving as an integral part of educational curricula. Many websites for China’s hacking contests prominently display their commitment to aligning with Xi’s vision of transforming the country into a cyber powerhouse, presenting this alignment as their core purpose. They highlight cyber-related goals and objectives drawn from various iterations of the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, held every five years, as well as specific legislation such as China’s Data Security Law and the country’s Five-Year Plans.

In September 2023, under the guidance of China’s Ministry of Education, the Discipline Evaluation Group of the Academic Degrees Committee of the State Council released its “White Paper on the Practical Ability of Cybersecurity Talents—Talent Evaluation.” The report emphasizes that colleges and universities with undergraduate programs play a crucial role in cultivating cybersecurity talent, accounting for 90 percent of the new workforce. Additionally, 63 percent of surveyed institutions found hacking competitions effective for training cybersecurity professionals. Among competing students, 45 percent began their participation in their freshman year, and 32 percent in their sophomore year, indicating that “cybersecurity competitions have become one of the most effective methods for colleges and universities to assess the practical skills of cybersecurity talent.” To further encourage involvement, 75 percent of colleges offered financial incentives to students who excel in these competitions, and 75 percent have allocated budgets for attack and defense laboratories designed to enhance students’ practical abilities through required courses.

Promoting homegrown CTFs and keeping China’s best hackers at home offers a few advantages.

- First, policymakers viewed software vulnerabilities—flaws in code that allow attackers to exploit targeted systems—as a national resource. It would be years before China mandated their total collection but, in 2018, China settled on stopping researchers from participating in foreign exploit competitions and collecting vulnerabilities at domestic competitions.

- Second, security services can learn new exploitation paths for common targets by watching how competitors attack their targets. Even without finding new vulnerabilities, observing other people’s exploits can improve attack methodologies.

- Third, if marketed effectively, hacking competitions can inspire high school students to consider a relevant degree at university. Influential educational bodies in China consider cybersecurity competitions an important way to promote the field.

- Fourth, in addition to requirements for continuing education and certifications, a robust ecosystem of CTFs allows students and practitioners to engage regularly in events designed to keep their skills fresh.

- Fifth, successful Chinese CTF participants have joined top domestic tech companies’ vulnerability research labs or founded cybersecurity startups offering specialized services, such as cyber ranges and automated vulnerability discovery systems, to Chinese companies and government agencies.

- Sixth, the government created an environment in which it could more easily entice China’s hackers to support its efforts through vulnerability research or other means, by proactively screening their travel abroad and creating a competitive ecosystem at home. Key CTF contests analyzed in this report are affiliated with the Ministry of State Security (MSS), PLA, and MPS serving as crucial talent-recruitment pipelines for security services.

Methodology

This report collected data mainly from three websites that host information about cybersecurity competitions in China (ichunqiu, XCTF, and CTFtime), but also included smaller data contributions from GitHub accounts, blogs, and WeChat accounts. The data set includes CTFs (Jeopardy or Attack-Defense), vulnerability competitions, and two competitions for technology development.

Our data are subject to significant inflation. There is no way to disambiguate competition participants across years. If a team of ten college students participates in a competition, two graduate, eight return the following year, and two new freshmen replace the two graduating seniors, then only twelve individuals will have participated over two years, but total attendee numbers will show twenty. Without the ability to deduplicate attendees, our numbers are best thought of as instances of participation, rather than individuals participating.

Whenever possible, attendance figures are first derived from the official competition website for each event. The second-most authoritative sources are the competition listing websites whose data were used to identify many of these competitions. Finally, if neither preceding figure could be found, then media accounts covering the event were acceptable. In the event that any of the sources identified the number of teams, rather than participants, and there was no other available sourcing, the authors used the most conservative estimate of four-person teams to determine the number of participants.

Some competitions had data available for some years and for some rounds (preliminary versus finals), but not all. To estimate the number of attendees for each year without data, we averaged the number of attendees during years for we had data and applied that number for missing instances. In cases where data were available for some rounds and not others, especially across years, we favored the use of preliminary rounds to calculate average annual attendees and did not count final rounds toward the aggregate competition number, as those attendees were already counted in the preliminary round. Additionally, many competition numbers did not include 2024 participation data, as our data were pulled in the first half of 2024 and many annual competitions occur in the fall. To estimate the number of unique annual hacking contests in China (Figure 2), we filtered out the qualification and semifinal rounds, retaining only the final rounds to avoid duplication and more accurately reflect standalone competitions.

China has a handful of competitions specifically to urge college students to produce new ideas for products that address cybersecurity issues (National College Student Information Security Contest, 全国大学生信息安全国赛; National Cryptographic Technology Competitions, 全国密码技术竞赛决赛). We excluded these product-focused innovation competitions. However, we included two research-focused competitions related to improving cyber defenses and the automation of software vulnerability discovery, on the grounds that these competitions included many of the same universities’ teams that participated in CTFs, included the use of the technology in an attack-defense testing dynamic, and were not exclusively predicated on the judgment of a panel and the award of investment money into a product idea. Additionally, competitions that were held by a single university for its own class or students were not included, as they are less individually significant, too numerous, and too difficult to identify in a comprehensive manner. Competitions listed on Chinese websites but hosted abroad by international organizations with no overlap with Chinese organizations (e.g., Google CTF) were also scrubbed from the data.

Some notes on coding of provincial or municipal government offices.

- Local MIIT offices (天津市工信局) were counted toward the MIIT.

- Local CAC offices (天津市委网信办) were counted toward the CAC.

- Local Government (某市人民政府) were counted toward the local government.

- Any subordinate organization counted toward its ministry.

- The China Academy of Engineering (中国工程院) was counted toward CAS.

- China Institute for Innovation and Development (国家创新与发展战略研究会) = MSS.

On the webpage and visualization, we excluded events that occurred once, were hosted by a university for that university’s own students, or were corporate events meant to provide crowd-sourced security to a company through public testing (e.g., H3C and Didi Chuxing competitions).

Key findings on China’s hacking contest ecosystem

China’s ecosystem for collegiate CTFs is the best in the world. Multiple CTFs bring together hundreds of college teams across the country to compete annually, including the Information Security Ironman Triathlon, Qiang Wang Cup, Wangding Cup, and National University Cyber Security League. The system is so robust, it is as if there are multiple National Collegiate Athletic Associations for collegiate hacking. The MPS, PLA, MSS, and Ministry of Education all support one or more national-level collegiate events. For the United States, an equivalent ecosystem would see national collegiate-level competitions held by the Department of Defense, the Director of National Intelligence, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Department of Education.

The following sections will explore this ecosystem in greater depth, examining the factors enabling its growth, the organizations hosting these contests, participation rates, sector-specific competitions, the role of cyber range companies, and a preliminary overview of an online database we have developed based on our collected and analyzed data.

1. Growth enablers

The number of domestic hacking competitions in China soared since 2014, following the success of Chinese teams in prestigious international contests. In 2013, Tsinghua University’s Blue Lotus team became the first Chinese team to compete in the DEF CON CTF finals in Las Vegas. In 2014, China’s Keen Team triumphed at the Pwn2Own contest in Vancouver, following its strong performance in the previous year’s Mobile Pwn2Own in Tokyo. The Blue Lotus team’s achievements significantly influenced China’s CTF hacking culture, leading to the creation of Baidu CTF (BCTF) and the XCTF International League, China’s largest CTF tournament, between 2013 and 2015. Keen Team’s success also led to the establishment of GeekPwn in 2014, an event modeled after Pwn2Own and now known as GeekCon. GeekPwn emerged during a time when Chinese tech companies and manufacturers were wary of hackers, often refusing to participate in competitions out of fear of reputational damage. Some hackers even attempted to disrupt GeekPwn’s inaugural event.

As Chinese teams’ successes abroad began to challenge previous taboos at home and highlight the strategic importance of cybersecurity talent, companies like Baidu, Tencent, and Qihoo 360 began sponsoring events, acquiring teams, and recruiting top talent. As a result, the number of hacking competitions in China proliferated. We found that China has hosted at least 129 unique events since 2004, with most occurring after 2014. Our dataset includes 554 rounds of competition (preliminary, semifinal, and final, as applicable) for these events. From 2017 to 2023, the number of hacking contests stabilized, with roughly thirty-seven to fifty-six unique events held annually during this period (see Figure 1). For a comprehensive list of specific events conducted each year between 2004 and 2023, refer to Appendix A.

In summary, the growth and prominence of China’s hacking contest ecosystem have been significantly encouraged and supported by the state, as noted in the policy section of this paper. However, the findings from this section also indicate that this ecosystem has been organically driven by China’s dynamic and highly skilled hacking community. This community has embraced the opportunities provided by government initiatives and fostered a culture of innovation and collaboration, creating a thriving ecosystem that combines state support with grassroots engagement.

2. Main annual events

Among the 129 unique events we have identified, fifty-four are annual competitions—fifty-one CTF contests, two exploit contests, and one combining both. An overview of these recurring competitions can be found in an online database we developed from our collected and analyzed data (see Figure 2 for a preview). Each competition features a placard that reveals additional details upon clicking, as illustrated in Figure 3. This information includes years of activity, average and total participation numbers, host organizations, and links to detailed competition write-ups.

Figure 2: CTF online database dashboard

Figure 3: CTF online database placard

3. Host organizations

While many of the fifty-four annual competitions are organized by private companies or universities, they also involve state institutions, as detailed in Figure 4. Competitions frequently have more than one sponsor, so sponsor association is not an exclusive quality (e.g., a competition might have MPS and CAC as sponsors).

4. Participation rate

Participation in China’s contests varies widely. Of the fifty-four recurring events identified, most attract between a few hundred and two thousand participants annually. The top ten contests draw from five thousand (in the case of the Huawei Cup) to more than thirty-five thousand (for the Wangding Cup), as shown in Figure 5.

5. Sector-specific contests

China’s CTF landscape is set apart by its wide range of sector-specific CTF contests, such as those for healthcare, law enforcement, mobile applications, cryptography, vehicles, and smart cities. These competitions are tailored to address the distinct cybersecurity challenges of each sector. For example, the National Health Industry Cyber Security Skills Competition (全国卫生健康行业网络安全技能大赛) tests participants’ cybersecurity skills in medical contexts. Competitors typically include information-technology (IT) and cybersecurity professionals from hospitals and healthcare organizations. Similarly, the National Industrial Control System Information Security Competition (全国工控系统信息安全攻防竞赛) and the National Industrial Internet Security Technology Skills Competition (全国工业互联网安全技术技能大赛) focus on industrial control systems, featuring attack and defense scenarios that include physical systems. The Blue Cap Cup (蓝帽杯), centered on law enforcement, draws participants from police academies nationwide and emphasizes electronic forensics and case investigation challenges alongside traditional CTF tracks.

6. Cyber ranges

Among the fifty-four recurring competitions identified in this report, most rely on either Beijing Integrity Tech (永信至诚) or Cyber Peace (赛宁网安) as their cyber range providers, while others develop in-house or ad hoc solutions tailored to specific contests.

In September 2024, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) announced that it had seized control of a botnet run by Integrity Tech in connection with the activities of the Chinese government-linked hacking group Flax Typhoon. This group targeted critical infrastructure in the United States, Taiwan, and globally, including corporations, media outlets, universities, and government agencies. Following the FBI statement, a joint advisory from the FBI, Cyber National Mission Force, and the National Security Agency (NSA) accused Chinese cybersecurity company Integrity Tech of compromising hundreds of thousands of Internet of Things (IoT) devices since 2021, with more than 260,000 devices affected by June 2024, spanning North and South America, Europe, Africa, Southeast Asia, and Australia. This is significant not only as a rare public outing of a company involved in state-sponsored malicious activities, but also due to Integrity Tech’s key role in China’s talent pipeline, both as a leading cyber range provider and through its active involvement in CTF contests.

Cyber ranges for at least twenty-six of the fifty-two recurring CTF hacking contests identified in this report are operated by Integrity Tech. These contests include some of the country’s most prestigious in terms of complexity, payouts, participation rates, and geographic reach. They are organized by both private companies and leading universities, such as the Matrix Cup, alongside government-sponsored events, such as the Information Security Ironman Triathlon, XCTF, Xiangyun Cup, Wangding Cup, and Qiang Wang Cup. Notably, competitions like the Wangding Cup and Qiang Wang, organized by the MPS and the PLA respectively, focus on IoT devices and vulnerability mining, reflecting the targets and activities for which Integrity Tech has been accused in the U.S. advisory.3031 Each of these events is analyzed in detail in the following sections.

As they provide simulated digital environments, cyber ranges collect and store performance data that state security services can leverage to gain insights into network configurations, vulnerabilities, and defenses, potentially informing real-world targeting strategies. Attackers can use these stored simulations and exercises to refine their techniques, reverse engineer attacks, and develop exploits, while also learning how defenders respond to craft strategies that bypass security measures. Although the extent is unclear, Integrity Tech’s capabilities as a leading cyber range provider likely enhanced its operational effectiveness in conducting cyber operations.

Notable competitions

We selectively highlight some competitions from our dataset. These were selected for their apparent ties to the military or security services, their relative size within China’s CTF ecosystem, or their association with efforts to develop technology. They are not provided in any particular order.

The Information Security Ironman Triathlon (信息安全铁人三项赛)

The Infosec Ironman Triathlon is designed to improve ties between industry and academia, and likely supports talent spotting by the MSS. The 2024 edition enters anyone qualifying for the semifinals into the National Cybersecurity Talent Database (国家网络安全人才库).

Jointly established by CNITSEC (MSS 13th Bureau) and the Ministry of Education in 2016, the Infosec Ironman Triathlon attracted more than three hundred universities for its 2024 edition. The competition is held annually, with subnational competitions around the country producing teams that qualify for the finals, called the Great Wall Cup (长城杯). The three legs of the triathlon include: Personal Computer Confrontation (个人计算环境安全对抗), which includes personal computers (PCs), smartphones, and wearables; Corporate Environment Confrontation (企业计算环境安全对抗), which includes penetration testing, large-systems management, and setting up defensive technology; and Information Security and Data Analysis Confrontation (信息安全数据分析对抗), which focuses on incident response and management.

The competition tightens relationships between universities and the cybersecurity industry by pairing the two on teams. Team structure requires one teacher from the university and another from industry (assigned by lottery), along with four competing students and two alternates.Organizers designed the structure of the teams specifically to encourage a feedback loop between what industry needs and expects from students, what universities teach, and what the competition demands of participants. To this end, the organization’s oversight structures are populated by China’s most influential cybersecurity companies, universities, and government organizations.

The Infosec Triathlon has also supported talent spotting since its inception. The inaugural competition selected ninety students to join a three-month “closed session” training camp (封闭集训), which included lectures from corporate sponsors, among others. At the end of the camp and after examination, a “talent committee” recommended students to be hired by members of the China Information Industry Trade Association.

Talent spotting has evolved since 2016, however. The 2024 Infosec Ironman Triathlon regulations—hosted on the MSS 13th Bureau’s website—state that “teams which reach the semi-finals and finals will receive certificates, prize money, and be entered into a National Cybersecurity Talent Database (国家网络安全人才库).” There are few mentions of this database available online. The earliest available mention is from press coverage of 2022 Nation Cybersecurity Week. That coverage suggests the database was founded by the National Cybersecurity Education and Technology Industry Fusion Test Zone (国家网络安全教育技术产业融合发展试验区), which has five locations throughout China and was also launched in 2022. The test zones are overseen by the CAC, MIIT, Ministry of Education, and Ministry of Science and Technology. The only other specific mention of the database is from the MSS’s National Cybersecurity Talent Cultivation Base website (国家网络空间安全人才培养基地, see discussion in CTFWar). If the database is meant to facilitate hiring into the private sector, it should be easy to find, readily searchable, and promoting the success of its talent placement into industry. The database is none of these things. The database might be privately maintained by the government, or it might be a project that has failed to launch and remains aspirational.

National Collegiate Cybersecurity Attack and Defense Competition “Zhujian Cup” (全国大学生网络安全攻防竞赛, “铸剑杯”)

The National Collegiate Cybersecurity Attack and Defense Competition may pit college students against actual intelligence-collection targets. There are a few state media pieces about the event, which was first held on New Year’s Eve 2023, and the language and images are tightly scripted. The competition appears normal at first glance. A piece from People’s Daily states that two hundred students from twenty-nine universities participated in the event. Images show speakers giving talks to the students in attendance.

The Zhujian Cup, as the competition is also known, is hosted by Northwestern Polytechnical University alongside known vulnerability suppliers to the Ministry of State Security and the Shanxi Provincial CAC. The university conducts defense-related work and is one of the “Seven Sons” universities of National Defense overseen by the State Administration of Science, Technology, and Industry. Eighteen months before the Zhujian Cup, state propagandists named the university an alleged victim of US hacking. The competition is also supported by the Shanxi branch of the National Cybersecurity Education and Technology Industry Fusion Test Zone (国家网络安全教育技术产业融合发展试验区), which hosts the National Cybersecurity Talent Database associated with the aforementioned Infosec Ironman Triathlon.

But unlike almost every other competition examined in our dataset (see also CTFWar below), there are no write-ups by participants. There are no posts on Twitter, Weibo, LinkedIn, Bilibili, or any other social media site about the competition. This secrecy is legally enforceable.

Prior to participating in the Zhujian Cup, students are required to fill out three documents. The first collects typical information, such as name, sex, picture, and competition history. But the second document is atypical. The “political examination form (政治调查表)” asks students to recount their “political and ideological work performance” and asks: “Have you received any awards or punishments, if so when and where?” “Do immediate family members have any significant problems?” and “Are there any problems in your main social relationships?” The questions and title of the document make clear it is intended to serve as a background check. Readers unfamiliar with China may reasonably question the severity of the background check, which does not probe for personal moral defects the way checks from Western governments do. But the competition’s political examination form aligns with what is understood about the political background-check process for PRC government employees.

The third document requires the student’s name, student number, and a signature. The content of that document, translated below, indicates that students are participating in a secretive competition and suggests that the target students are attacking is an actual intelligence-collection target. Critically, students promise not to disrupt the availability of the system they are attacking, nor cause a destructive impact to it; both are important stipulations if they are trying to conduct espionage undetected. Students affirmatively commit to “assist in deleting and removing the acquired data, and deleting and removing backdoor programs uploaded to the target system, and will not privately retain any data or backdoors.” The document continues, stating that various electronic and paper media will not be kept by the students, that such content should not be made public, and that the students are legally responsible for maintaining the secrecy of the information. If a leak occurs, students agree in Section 9 to bear responsibility for damages caused to the “competition host and the country.”

None of these requirements are standard for CTFs. Competitions typically occur entirely on a network established specifically for the competition, which functions as a cyber range. There are no data to delete and no backdoors to delete during regular competitions.

But swearing to secrecy, filling out a background check, accepting responsibility for damages to the nation, and promising to remove acquired data and delete backdoors on targeted systems are not the only atypical indicators of the Zhujian Cup’s activity. First, the Northwestern Polytechnical University website for the event lists the date of the competition as December 30–31, 2023. In parenthesis, the authors clarify that this date is for the “public environment actual confrontation competition (公开环境现场实战比赛),” begging the question of why it clarifies that this part of the competition is public. Second, the date itself—the weekend of New Year’s Eve—is an excellent time to attack foreign targets whose defenders are frequently either on holiday, inebriated, or both. Third, the university named this section of the competition the “public network-target, actual combat attack competition.” Finally, none of the organizations sponsoring the competition are known for offering cyber range technologies. Most competitions identified either Beijing Integrity Tech or Cyber Peace as their range provider. The Zhujian Cup has no such provider, raising further questions about the nature of the competition.

We acknowledge that there is no conclusive proof that the Zhujian Cup prompted students to attack an actual intelligence target. However, we note that such a competition is likely not without precedent. Intrusion Truth tied APT40 to hacking competitions at Hainan University, showing they were used to find vulnerabilities and recruit students. Years later, the Financial Times reported that the Hainan MSS bureau had hired students to translate stolen documents. Separately, infrastructure associated with a competition at Southeast University overlaps with infrastructure from the hack of Anthem Insurance, and the timeline of the university’s competition aligned with attacks against a US defense industrial base company. The connections between that competition infrastructure and the timeline of the attempted hack create circumstantial evidence that the competition targeted the company. Finally, Northwestern Polytechnical University holds a Top Secret clearance, allowing it to undertake sensitive work.

Translation:

2. In the course of executing an authorized attack, I commit: to launching attacks on authorized attack targets according to the rules regarding constraints and without affecting service availability, such that the attacks will not have a destructive effect on target systems; and to assisting in deleting and removing the acquired data, and deleting and removing backdoor programs uploaded to the target system, and will not privately retain any data or backdoors.

3. I commit not to reproduce (or photocopy) without permission any materials, documents and electronic data, disk or paper media files, images, video materials, etc. used for completing assigned tasks and, if doing so is truly necessary for the work, to ask the competition organizer for approval.

4. I commit to properly storing the materials, documents and electronic data, disk or paper media files, images, video materials, etc. provided by the organizer for completing the assigned tasks, so as to prevent loss and theft.

5. I commit not to publicize or report the content of the tasks in any way within the unit or externally, and not to disseminate to third parties in any way the materials, documents and electronic data, disk or paper media files, images, video materials, etc. provided by the organizer for completing the assigned tasks.

6. I promise that, if the organizer imposes corrective requirements for matters of non-compliance with the terms of confidentiality, I will promptly conduct self-inspection and self-correction and cooperate in any investigation and penalties without delay or concealment.

7. I commit not to disclose or exploit data related to critical information infrastructure and system vulnerabilities discovered during the competition, and not to provide or publish externally any vulnerabilities or any information from the competition process.

8. I commit to promptly reporting to the organizer any loss or theft, regardless of the cause, of information provided by the organizer or of information generated by myself or jointly with others, and will actively cooperate with the organizer and local public security authorities in their investigation.

9. I promise that if any information disclosure incident (or case) occurs due to personal reasons, causing loss or harm to the organizer and the country, I, as an individual, will bear legal responsibility in accordance with the relevant laws and regulations.

CTFWar (国际网络安全攻防对抗联赛)

CTFWar is both a cybersecurity competition and a website with practice material and user profiles that likely enable talent spotting by the Ministry of State Security. Since 2021, CTFWar has been hosted under the guidance of the MSS’s own National Cybersecurity Talent Cultivation Base (国家网络空间安全人才培养基地), an institution formed by the Ministry of State Security’s 13th Bureau (CNITSEC, 中国信息安全测评中心) and Beijing University of Chemical Technology (北京化工大学). Beijing Hua Yun (Vul.AI, 华云信安(深圳)科技有限公司), a Tier 1 supplier of vulnerabilities to the MSS, helps administer CTFWar. The competition hosts six regional competitions across China, which feed into the final competition. CTFWar participants are likely subject to constraints regarding discussing their participation or the event online. As with the Zhujian Cup above, there are no write-ups available about the content of the competition, though we did not find any nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) online.

The CTFWar website has a plethora of resources for training and practicing common cybersecurity skills, vulnerability discovery, and attack and defense. Registered users of the training platform maintain their own profiles with competition history, learned skills, and points earned along the way (see below). For any government administrators sitting on the other side of the website, a list of high-performing users could serve as a talent-recruitment pool.

Figure 6: The loading page of a blank profile.

Figure 7: CTFWar provides its users learning opportunities and content across six categories (web, pwn, mobile, crypto, reverse, and miscellaneous) and organizes that content by difficulty.

Figure 8: This screenshot shows the “vulnerability discovery range.” The range’s content includes classes and demonstrations organized by product, difficulty, and vulnerability types. Here users can practice identifying known vulnerabilities (n-days) that have been reintroduced to products.

But CTFWar is not the National Cybersecurity Talent Cultivation Base’s only focus. The base, established in 2019, has facilitated at least three other one-time competitions, partnered with several universities for training, and participated in forums on cybersecurity and talent cultivation. Elsewhere, the base focuses much of its efforts on the promotion of, and the testing to qualify for, a number of cybersecurity certificates issued by CNITSEC. A handful of universities partner with the base to serve as a talent transport centers (人才输送中心), which suggests the university is certified to administer official tests for those certifications.

Wangding Cup (网鼎杯)

The Ministry of Public Security, China’s domestic security and intelligence agency, uses the Wangding Cup to identify potential recruits for its Cybersecurity Thousand Talents Program (网络安全千人计划). The talent program signals to potential employers that the recruit is exceptional, and likely provides direct financial benefits and indirect awards, though the award program’s benefits are not public.

Hosted by the State Cryptographic Administration (国家密码管理局) and the National Cyber and Information Security Information Bulletin Center (国家网络与信息安全信息通报中心), an organization subordinate to the MPS, the competition drew more than fifty thousand participants in a single year at peak participation. Based on our data, the Wangding Cup is the largest annual competition in China. Teams from across society participate. A list of 2020 competition winners shows teams affiliated with universities, critical-infrastructure operators, MPS offices, and private-sector firms among its champions.

Figure 9: Ministry of Public Security Periodical on the Wangding Cup, stating competition types include vulnerability discovery, exploitation, and patching, as well as integrating artificial intelligence for its Robot Hacking Games competition.

Besides typical competition structure, the Wangding Cup also integrates a Robot Hacking Game competition. This competition type, modeled off the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s Cyber Grand Challenge in the United States, tests competitors on their ability to utilize artificial intelligence (AI) for vulnerability discovery and exploitation. Its inclusion demonstrates China’s commitment to developing and deploying such tools.

Qiang Wang Cup (强网杯)

The Qiang Wang Cup is co-hosted by the PLA Information Engineering University and receives support from China’s World-Class Cybersecurity Schools—a group of universities recognized by the government for their excellence in cybersecurity education. If a comparable event were to take place in the United States, it would include all the service branches’ cyber training academies, like US Air Force Cybersecurity University, and the universities certified as Centers of Academic Excellence (CAE) in Cyber Operations by the jointly run National Security Agency and Department of Homeland Security CAE program. Despite the proximity between the PLA and these elite universities, we did not find evidence of formal recruitment programs seeking participants. However, it is unlikely the military would forgo such an opportunity.

The Qiang Wang Cup has an online qualifying round, an in-person round, and an elite round. The cup’s elite round pays out more than most other competitions in our dataset. After qualifying for the elite round, teams compete to successfully “answer” (相应) challenges (赛题) for a number of “fields of study” (科目). Each challenge is worth somewhere between 20,000 and 200,000 renminbi (RMB). Such payouts are typically offered at exploit competitions, in which competitors burn valuable vulnerabilities for cash. We were unable to find details about what constituted a challenge for the elite competition round.

The teams qualifying for the finals each year are a diverse set of critical-infrastructure operators, private-sector companies, or top-tier universities. Military institutions are also frequently listed among the thirty-two teams qualifying to participate in the finals each year, such as the PLA’s National University of Defense Technology.

Qiang Wang International Elite Competition for Cyber Mimic Defense (“强网”拟态防御国际精英挑战赛)

The Competition for Cyber Mimic Defense is a PLA-run competition that supports the development of cyber mimic technology, a state priority identified by past development plans. Competitions are an effective way to jumpstart research into a specific technology, and this competition betrays significant interest in the technology by the PLA. Although the competition name also includes Qiang Wang, this competition is held separate from the competition discussed above.

Wu Jiangxing, a Chinese Academy of Engineering member and father of cyber mimic defense in China, is the progenitor of this competition. Cyber mimic defense is a technique used by defenders to introduce randomness and redundancy into the architecture of computer systems. Randomness creates a lack of predictability that forces attackers to spend more time and resources, while redundancy enables the detection of attacks. The technique is uncommon in commercial cyber-defense products and is hard to execute well. Since 2018, the PLA’s Purple Mountain Laboratory, the Chinese Academy of Engineering, and the Nanjing government have hosted the Competition for Cyber Mimic Defense every year. Both Purple Mountain Lab and the Chinese Academy of Engineering would be able to act on innovations brought to the competition.

The development of cyber mimic defense technology is a priority for China. A publication by the State Key Laboratory for Information Security credits Wu with positing the possibilities offered by cyber mimic defense in 2008. That same publication states the 863 Development Plan—a high-tech development plan—began prioritizing the technology in 2016, two years before the start of the competition. Governments frequently use competitions to stimulate innovation of a technology’s development; the Competition for Cyber Mimic Defense falls into this camp. Participants are not only directly demonstrating advances in techniques to the competition’s organizers—including the PLA’s Purple Mountain Laboratory—but are also forming social relations that last after the competition concludes. These relationships are often the most important intangible boosters of scientific research.

The competition’s first and second years saw the most international participation—attracting teams from Japan, Russia, Ukraine, and the United States. Since then, foreign participation—or qualification—has seemingly dropped. Although the name indicates the competition is open to international participants, recent lists of the competition’s top performers include only Chinese teams.

RealWorldCTF

RealWorldCTF draws foreign hackers into China and has facilitated at least one initial contact by Chinese security services to an American attendee. That person’s story, recounted below, indicates that competition staff was involved in the pitch. We find it likely that such pitches continue today. Real World CTF occurs annually, continues to draw foreign participants, and is sponsored by Beijing Chaitin—a company that is a Tier 2 Technical Support Unit of the MSS.

After the first day of the competition, Matt and his team had been chatting with a team from the UK. With different interests in dinner between the eight of them, four decided to head downtown for dinner, and the remaining two UK players, Matt, and another American stayed near the hotel instead. They walked as a group towards a shopping center near the conference center. Because the subway stop at the facilities had not been built yet, the area was only populated with conference attendees and people working at the shops.

Shortly after sitting down for hotpot, Matt noticed two women from the conference walk past the front of the restaurant. “I recognized one of them because she was involved in the Real World CTF organization. She had been walking around with a microphone and directing people.” The women ended up eating dinner in the same restaurant in the back corner of the room. When Matt and his crew tried to pay their bill for dinner, a cook came out from the kitchen and told the four guys the meal had already been paid for, gesturing towards the women in the back of the seating area.

On cue, the women came over to the table and tried to chat up the four attendees. Their questions were the kind of short and stilted questions that someone repeating rehearsed sentences in a second language might say after a short period of study. After a few awkward moments and seemingly without good reason, the women offered Matt a torn scrap of notebook paper. On it, there were the words “phone number, telegram, whatsapp, and email,” each with a line next to it—the women, whoever they were, clearly hoped to stay in touch. Matt jotted down a Google VOIP phone number he had created and nothing else. The women thanked the four and were on their way.

After the competition and back home in the United States, Matt checked his VOIP number on his laptop. The phone number had received an MMS image file. He never opened it and deleted the number from his Google account.

We don’t know how many other attendees received free meals or had their contact information collected that year or in the years since.

GeekCon (previously GeekPwn)

If RealWorldCTF draws foreigners into China for hacking competitions, GeekCon goes abroad to seek them out. Created by members of the elite Keen Team, GeekCon was originally hosted as GeekPwn within China from 2014 to 2021.

The competition inside China hosted both conference talks and 0day demonstrations. Instead of creating a list of target systems as is standard at exploit competitions like Pwn2Own and Tianfu Cup, GeekPwn invited applicants to submit their own 0days of interest. A panel then picked the most compelling submissions. An archived version of the GeekPwn website from 2021 states that, in order for a GeekPwn vulnerability contest winner to receive their award money, the participant must provide a detailed explanation of the “security issue and technical methods” associated with the vulnerability. The organizers go on to state that they respect individuals’ privacy and will not expose the vulnerability information to the outside world. Effectively, the organizers would have the information all to themselves for the cost of the award. A 2014 post on Twitter shows the organization offering $100,000 for pwning a Tesla.

After a year off from competitions in 2022, GeekCon was reestablished in Singapore in 2023. With the same structure as inside China, GeekCon invites conference talk submissions, as well as 0day submissions.

GeekCon’s website suggests the competition, despite operating abroad, abides by Chinese regulations. The sixth rule for the event states, “As the top 1 security geek IP operator in China, we always advocate a reward mechanism that emphasizes both honor and moderate bounty.” Providing a “moderate bounty” is exactly what is required by the Cyberspace Administration of China’s 2018 Notice on CTFs (see the background section above).

We do not know if GeekCon submits the vulnerabilities of its participants into the mandatory reporting system run by the MIIT and introduced in 2021. Under a strict reading of the law, the competition’s participants are required to tell the company whose product is vulnerable, and no one else, until a patch is made public. In practice, some members of the cybersecurity community in China report into the new system out of fear. Additionally, if GeekCon attendees from China are applying to the MPS to leave China for the competition, they might already be providing their GeekCon submissions to the government. Darknavy, the company behind GeekCon, claims to have facilitated the responsible disclosure of more than one thousand severe software vulnerabilities. It is entirely possible that GeekCon is hosted overseas to escape China’s claim to the software vulnerabilities disclosed at its competition. The year reprieve from hosting the competition occurred just after the new regulations on software vulnerabilities went into effect. GeekCon did not respond to the authors’ request for comment to clarify its process. Still, the competition’s emphasis on “moderate bounty” suggests the organizers are a rule-following bunch.

XCTF League (XCTF国际网络攻防联赛)

Tsinghua University’s Blue Lotus team founded the XCTF League in 2014, one year after it made history as the first Chinese team to reach the finals of DEF CON CTF. XCTF was the first Attack-Defense CTF competition established in China and has since grown into the largest CTF league in the country. According to XCTF’s own website, it is the largest contest brand in Asia and the second globally, likely referring to DEF CON CTF as the first. As such, it serves as a crucial platform for identifying and nurturing high-end cybersecurity talent.

The competition is now organized annually by Cyber Peace, a company founded in 2013, and is co-organized by the Blue Lotus team and the China Institute for Innovation and Development Strategy (CIIDS, 国家创新与发展战略研究会). Although CIIDS presents itself as a non-profit organization, it maintains close ties to the MSS and is led by former MSS officers who previously handled front organizations and influence campaigns, as outlined by Alex Joske in Spies and Lies.

The MSS 12th Bureau, also known as the Social Investigations Bureau, is responsible for influence operations against individuals and facilitating elite capture. In short, the 12th Bureau aims to shape the views of thought leaders, business executives, and politicians in foreign countries. As a cover organization, CIIDS sponsorship of XCTF is aligned with its attendant work under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, rather than its association with the MSS.

The XCTF League operates more like a tournament than a single event, consisting of a series of selection rounds that span several months leading up to the final stage. The qualification stage includes multiple regional Jeopardy-style competitions that vary annually. These partner competitions are typically organized by university hacking teams and private research laboratories across the country. Between 2014 and 2023, approximately five to ten regional competitions annually have served as XCTF qualifiers, including prestigious events like 0CTF/TCTF. The XCTF finals adopt an Attack-Defense format, in which participants compete for the championship, runner-up, third place, and other prizes. In the 2023 XCTF edition, the rewards amounted to nearly $14,000 for first place, $7,000 for second place, and $3,500 for third place—amounts higher than those of other domestic CTF competitions.

Although primarily focused on China, XCTF has a strong international reach. Since 2019, its qualifying contests have included the CyBRICS and BRICS+CTF contests, organized by Russian CTF teams and aimed specifically at participants from BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) countries. In 2018, it partnered with Hack in the Box (HITB) to host XCTF international iterations in cities such as Dubai and Singapore. As in previous editions, the 2024 XCTF qualifying rounds attracted a massive number of participants: 2,987 teams consisting of more than eleven thousand contestants, with twenty-four domestic and international teams qualifying for the finals, according to a write-up by China’s National University of Defense Technology.

The Matrix Cup (矩阵杯网络安全大赛)

The Matrix Cup is China’s newest exploit competition. The inaugural Matrix Cup, held in Qingdao, Shandong Province from May to June 2024, was organized by 360 Digital Security Group and Beijing Huayunan Information Technology Co. (VUL.AI). The event’s scope was significant, combining three main competition styles into five challenges: three vulnerability mining challenges, one Attack-Defense CTF, and one AI challenge. With a prize pool totaling $2.75 million, the Matrix Cup exceeded the rewards offered by both Pwn2Own’s $1.1 million (2024) and the Tianfu Cup’s $1.4 million (2023). More than 90 percent of the prize money was allocated to vulnerability-related challenges, targeting both Western and Chinese systems.

Unlike the Tianfu Cup, the Matrix Cup did not disclose its targets and results. However, SecurityWeek reported a list of targets more than a month before the event. These included Windows, Linux, and macOS operating systems; Google Pixel, iPhone, and Chinese smartphone brands; and networking devices. A post-competition write-up by 360 Digital Security revealed that around one hundred vulnerabilities were discovered, with significant findings in virtualization platforms and mobile operating systems. Teams from Tsinghua and Zhejiang Universities excelled, with Tsinghua students securing top rankings in all five challenges, as highlighted in a university blog post.

The high rankings of university teams and the strong presence of Generation Z participants highlighted strong participation from academia over industry. Zhou Hongyi, founder of 360 Group, highlighted that the Matrix Cup focuses on talent development, aiming to discover, train, and recruit top cybersecurity talent.

Figure 10: Final ranking of the general products contest.

https://web.archive.org/web/20240708061854/https:/360.net/about/news/article66836ac56ddf08001f91a723#menu.

Vulnerabilities discovered during the Matrix Cup were likely reported to the MSS. Chinese hacking competitions, such as the Tianfu Cup, have been linked to state-sponsored activities in the past. In addition, the event’s organizers, 360 Digital Security Group and VUL.AI, are Tier 1 MSS vulnerabilities suppliers, while co-organizers Cyber Peace and Beijing Integrity Tech are Tier 2 suppliers.

The Xiangyun Cup (祥云杯)

The Xiangyun Cup warrants additional scrutiny. Jilin provincial government and the local MSS13th Bureau (中国信息安全测评中心吉林分中心) co-sponsor the competition. Started in 2020, the Xiangyun Cup has two tracks—one for the public and one for college students. The public CTF track provides significantly above-average payouts for winners—grand champions take home 200,000 RMB (approximately $28,000) for the team. Most competitions we observed pay far less, typically around 50,000–100,000 RMB (approximately $7,000–14,000). The award amount even exceeds the 2023 Tianfu Cup bounty for local privilege escalation vulnerabilities on Windows 11 (150,000 RMB, or approximately $21,000). Besides flashy graphics and coverage by the Jilin provincial education department, there is little information available about the competition that would indicate why its award is above average.. The local government may be flush with cash, unaware of the going price of CTF championships, trying to attract high-end talent for political points, or attempting to boost attendance for other reasons.

Conclusion

Following its 2018 policy document on hacking competitions, China’s CTF ecosystem flourished. Our data from the ten most popular competitions show more than one hundred thousand instances of participation annually. Further research is needed to quantify the size of the ecosystem outside China. We suspect China outstrips any individual country in annual participation, but might find itself on par with the United States and its treaty allies if numbers are evaluated together. Regardless of how the rest of the world fares, it is clear that China’s policymakers and ministries have successfully built a comprehensive system for hacking competitions.

CTF contests serve as powerful tools to identify and recruit top cybersecurity talent, enhance skill development, and drive innovation. Key CTF contests analyzed in this report, including the Information Security Ironman Triathlon, CTFWar, Qiang Wang Cup, and Wangding Cup, are affiliated with the MSS, PLA, and the MPS, serving as crucial talent-recruitment pipelines for security services. RealWorldCTF and GeekCon facilitate China’s interaction with foreign hackers—RealWorldCTF brings them to China and GeekCon meets them abroad in Singapore. As China’s largest and most prestigious CTF contest, the XCTF League stands out as the country’s premier talent-development platform, with multiple qualification rounds held nationwide throughout the year. Other competitions, such as X-NUCA, specifically rally college students to practice their skills. Elsewhere, the Qiang Wang International Elite Competition demonstrates how contests can foster the development of cutting-edge technologies like cyber mimic defense.

China’s system should inspire policymakers outside the country to catch up. A diverse group of ministries and private companies host hacking competitions. The result is a cohort of potential hires across economic sectors who have regular, hands-on practice with some key tenets of cybersecurity. Some competitions are purposefully designed to improve coordination between academic curricula and the private sector (e.g., Infosec Ironman Triathlon), while others simply allow college students to hone their skills outside the classroom.

Sector-specific contests, like those focusing on healthcare, offer a compelling example. Companies facing common threat actors and operating under a single regulatory regime may benefit from closer cooperation and communication among defenders. Relationships with other line-level defenders across industry will likely yield better cooperation than conferences for managers and C-suite of the same industry. Some Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) in the United States have already started hosting such competitions; others should follow suit.

We hope our report serves as the first of many delving into competitions in China. The data we made available with this report should enable follow-on research. Specifically, future studies could examine the various types of CTF competitions in greater detail, including their organization and structure, and explore how these formats might be adapted to different national contexts. Furthermore, innovation-focused competitions—those in which students present ideas for new technology or businesses—fell outside the scope of our review; these should be studied for their impact on the development of China’s cybersecurity industry. China spent the five years from 2014 to 2019 recreating the US cybersecurity education system in the hopes of copying its success. Now, we think it is time for the United States to take a page from China’s playbook.

Key recommendations

The following recommendations include ways for other countries to draw on China’s CTF ecosystem to enhance talent identification and development, as well as to implement security measures to protect against the potential threats highlighted in this report.

1. Policymakers should promote the integration of CTF contests into academic curricula, as they effectively assess practical skills through rankings, prizes, and specialization. This approach can also align education with industry needs and strengthen the capabilities of the cybersecurity workforce. In the United States, this could be achieved by changing the criteria for the US Centers of Academic Excellence in Cyber Defense to include participation in CTFs or similar practical modules.

2. National critical infrastructure agencies should host CTFs for their sector. This approach would enhance sector-specific defenses and improve capabilities. This sector-specific approach would yield tangible benefits by way of hands-on skills and familiarity with tooling. Intangible benefits would result, too. Competition between companies in the same sector would help chief information security officers benchmark their security teams against one another, improve relationships between defenders in the same sector, and increase interaction between regulators and their sector. In the United States, sector risk-management agencies should host CTFs.

Appendix A

Hacking Contests in China by Year (2004–2023)

About the authors

Eugenio Benincasa

Senior Researcher, Cyberdefense Project, Risk and Resilience Team

Center for Security Studies, ETH Zurich

Explore the program

The Global China Hub researches and devises allied solutions to the global challenges posed by China’s rise, leveraging and amplifying the ’s work on China across its sixteen programs and centers.

Image: Shutterstock