Somewhere on the Chinese internet there is a science fiction novel that has been in the works since 2009 and will probably never be finished. It is titled ‘Illumine Lingao’ (临高启明, translatable as “The Morning Star of Lingao”) and accumulates millions of words distributed over thousands of chapters. It does not have a single author: it has been written collectively by hundreds of people, mostly engineers, technicians and military history fans who have been contributing chapters, technical corrections and secondary plots over almost two decades. It has generated more than 1,400 derivative works. And it has never been translated into any Western language.

What is it about? The premise is simple: more than 500 21st century Chinese citizens, armed with modern technical knowledge, travel back in time through a wormhole to the year 1628, to the death throes of the Ming Dynasty. They settle in Lingao County, on the island of Hainan, and from there they unleash an industrial revolution that alters the course of history. The goal: make China reach modernity before Europe.

How it arises. The text began to take shape in 2006 as a discussion on SC BBS, the oldest military-themed forum in China, from a question that struck a chord: “What would you do if you could travel to the Ming dynasty with modern knowledge?” The debate crystallized three years later in a collective writing project led by a user known as Boaster, whose real name is Xiao Feng. The first installment was published in 2009 on Qidian Chinese Network, the country’s largest web literature platform. In 2017, China Radio, Film & TV Press published the first volume in print format.

What makes it special. What sets ‘Illumine Lingao’ apart from other time travel fantasies is its obsession with technical detail. The chapters include long discussions on how to make nitric acid from scratch, what materials are needed to build chemical synthesis towers, or how many tons of industrial equipment would be needed to begin mechanization without prior machines or tools. Chinese readers have dubbed it “the encyclopedia of time travel.” Some critics consider it “a unique phenomenon of contemporary Chinese literature.” But… what sensitive chord does this work touch?

el puzzle de needham. In 1942, the British biochemist Joseph Needham traveled to China as a diplomatic envoy. During those three years he discovered that the Chinese had developed techniques and mechanisms that preceded their European equivalents by centuries. The printing press, the compass, gunpowder, paper money, suspension bridges, toilet paper… all had emerged in China long before Europe even conceived of it. Needham returned to Cambridge and documented this in ‘Science and Civilization in China’, 25 volumes that asked why modern science and the industrial revolution developed in Europe and not China, if China was so far ahead.

This question, known as “Needham’s puzzle”, touches the most sensitive nerve of Chinese historical consciousness. Historians have proposed dozens of answers. Some point to geographical factors: while Europe competed fragmented into rival states that stimulated military and commercial innovation, China remained unified under a bureaucratic system that did not need change to survive. Others point to philosophical reasons: Confucianism valued social harmony over disruption. And some say that the key difference was European access to the resources of the American continent.

For Chinese intellectuals, the “Great Divergence”, the moment when Europe overtook China, is not an abstract problem for historians. It is the question that explains the “century of national humiliation” (1839-1949), the opium wars, the burning of the Summer Palace and the Japanese occupation. That is why in ‘Illumine Lingao’ we travel to the Ming dynasty: 1628, sixteen years before the dynasty collapsed due to the Manchu invasion. For these Chinese intellectuals, the Ming dynasty represents the fateful fork: it is the moment when China chose the wrong path and Europe took the lead.

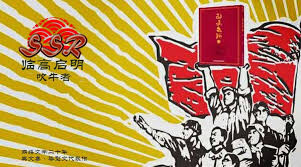

Rewrite history. ‘Illumine Lingao’ belongs to a literary genre that is enormously popular in Chinese web literature: chuanyue (穿越), time travel stories in which contemporary protagonists use their modern knowledge to alter the course of history. In China, this genre has an implicit nationalist charge. It is not about looking at the past or resolving temporal paradoxes, but about correcting it, giving China a second chance. ‘Illumine Lingao’ takes this premise to the extreme: the documentation of each step with obsessive technical rigor turns the novel into something more than entertainment. It is a manual and a manifesto. A manifesto of a specific party.

More than entertainment. As has been analyzed in academic circles, ‘Lingao’ reorganizes the historical narrative of Chinese socialist construction around the framework of industrialization and technological progress, with a clear nationalist sense. Its roots are in the so-called Industrial Party, which is not a real party, but rather a label to designate a current of thinkers, online commentators and influencers who share a vision of the world based on industrialization as a supreme value.

For them, the material transformation produced by industrialization is an objective measure of national success. At the beginning of this century, its area of theoretical development was the Internet, going against the grain at a time when the Chinese economy was betting on low-cost manufacturing and foreign direct investment. At the time, the idea that China could manufacture advanced semiconductors sounded like science fiction. The Industrial Party made the leap to public influence in 2012, when the news website Guancha began to include party members among its editors, defending the Chinese government from ultra-nationalist positions.

Cultural battle. ‘Lingao’ has also largely become a political tool. When in 2011 a high-speed train hit another convoy from behind, causing 40 deaths and 192 injuries, the Government wanted to manage the information so that the idea of prosperity at any cost was not clouded. But on social networks, negative opinions about the accident surpassed even the state censors and cast doubt on the idea of ”progress” that the government maintained. Was the speed of development exacting an unacceptable Price in human terms?

‘Illumine Lingao’ became a reference text in the ensuing cultural battle. The post-Wenzhou debate gave new relevance to the text: the book demonstrated with technical rigor how a group of Chinese with engineering knowledge could build an industrial civilization from scratch. As the ideologues of the Industrial Party defended, if 500 people could industrialize 17th century China, how could 21st century China be stopped by a railway accident? It is a complex issue that books such as ‘Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future’, published in 2025 by Dan Wang, attempt to analyze its multiple variables.

A monstrous project. Perhaps the most interesting thing about ‘Lingao’ is not the results (there are dozens of endings that contradict each other, and it is far from being a closed project), but its very existence: a mirror of the aspirations and anxieties of contemporary China, and an exorcism of numerous historical traumas. The novel does not reflect the contradictions and potholes that China has gone through and is going through, as happens to any regime of this magnitude, with millions of small pieces in simultaneous movement. Perhaps that is the next challenge for the 500 experts who traveled to the past: to continue expressing the concerns of Chinese society in the novel, and for it to become an entity as infinitely complex as the country that serves as its model.

Photo by Xi Wang on Unsplash

In WorldOfSoftware | 200 drones in the hands of a single soldier: China is advancing very quickly in a type of war that seemed like science fiction