The concentration of wealth in a few hands that we see today in technological billionaires is not a new phenomenon. More than two thousand years ago, Ancient Rome faced exactly the same dilemma that today worries governments around the world: a few rich people accumulated land and resources, while the majority of citizens became impoverished to the point of bordering on misery.

A young politician named Tiberius Sempronius Playo He thought he found a solution to redistribute the wealth accumulated by the Roman patricians: his idea cost him his life.

By the mid-2nd century BC, after destroying Carthage and Corinth, Rome had become the dominant power in the Mediterranean. However, this expansion did not enrich everyone equally.

For the humblest Roman peasants, it brought a devastating social crisis. The small landowners, who for centuries had cultivated their lands and served in the Roman legions, were displaced by large estates exploited with slave labor brought from the new conquered territories.

The long military campaigns had prevented the soldiers peasants return in time to harvest their lands, which affected the economies of their families. Furthermore, upon their return they discovered that their lands had been expropriated by millionaire aristocrats from Rome.

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, grandson of Scipio Africanus, the general who defeated the Carthaginian Hannibal, and heir to one of the most powerful families in Rome, was guaranteed a brilliant political future. However, in 133 BC, being elected tribune of the plebs, he decided to propose an agrarian reform with which he attempted to redistribute the enormous fortunes that Roman landowners had accumulated. Something similar to what California is trying to do and other countries all over the world.

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus

With this measure, Gracchus was directly confronting his own people since he himself came from a wealthy family. Its law established that no citizen could own more than 500 acres (about 125 hectares) of public land, the so-called public field.

The plots that exceed that limit will be expropriated and handed over to landless peasants. A measure that, de facto, ended with the large estates in the hands of the richest Romans. The goal of the measure was twofold: to restore economic solvency to the Roman people and to ensure that Rome had enough citizens with assets to nourish its legions, since only property owners could serve as soldiers.

Making friends among the richest

According to Plutarch’s ancient sources, written between 96 AD and 117 AD, Tiberius was not seeking to start a revolution against the rich, but rather to restore old republican laws that had fallen into disuse.

To defend his reform, Tiberius gave speeches in front of the impoverished people of Rome. In one of his most famous, which was recorded by Plutarch, the young tribune declared: “Their generals deceive them when, in battle, they encourage them to fight for the temples of their gods and for the tombs of their fathers. This is because, of a large number of Romans, not one has his own domestic altar or family tomb. They fight and die to feed the opulence and luxury of others, and, when they claim to be masters of the whole world, they do not even own a piece of land.”

The Senate, dominated by large landowners, tried to block the reform by all means. They persuaded another tribune named Octavius to veto the proposal, but Tiberius responded with a bold and unprecedented maneuver: he called for the assembly to remove Octavius from office for acting against the interests of the people.

The reform was finally approved and applied by distributing the large estates of the landowners among the Roman peasants. However, when Tiberius attempted to run for a second term as tribune, a practice then considered contrary to Roman tradition, the aristocracy decided he had gone too far.

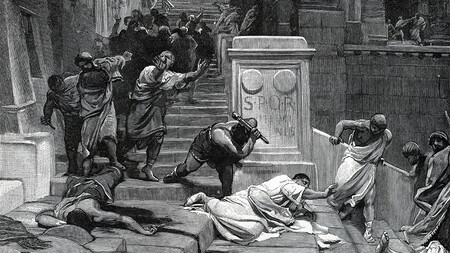

According to the historical documentation, during the elections in the Capitol, a group of senators led by the maximum pontiff Scipio Nasica, a relative of Tiberius himself, burst in with a group of followers armed with clubs and with the legs of chairs torn from the Curia. In the sacred place, where swords were not allowed, They beat Tiberius to death and about 300 of his followers. His body was thrown into the Tiber River without allowing his family to bury him.

Death of Tiberius Gracchus

Ten years later, in 123 BC, Tiberius’s brother, Gaius Sempronius Gracchus, took up the cause started by his brother with an even more ambitious program.

Gaius approved the Lex Frumentaria, which obliged the State to distribute wheat to the common people at below-market prices, laying the foundations for the system of food subsidies that would last for centuries.

He also proposed extending Roman citizenship to the Italic peoples who fought in Rome’s wars but did not enjoy its benefits. The Senate used populist tactics, warning that Italian foreigners would reduce aid to Roman citizens, and when Gaius lost popular support, he was pursued to the Aventine Hill near Rome, where he ordered his faithful slave Philocrates to assassinate him. Nearly 3,000 of his supporters died with him.

The legacy that survived violence

Although the Senate murdered both brothers, it could not erase their legacy. The reforms that the Gracchi had proposed would finally be implemented decades later by order of Julius Caesar, who had a powerful army that protected him from suffering the same fate.

The historians Plutarch and Appian recorded what happened to the Gracchus brothers centuries later. Both agreed to portray Tiberius as a politician with solid ideas who looked to Rome’s past to find solutions to the problems suffered by his people.

Paradoxically, although the story of the Gracchus brothers happened more than 2,000 years ago, we could find very similar references today with just a quick look at the news.

In WorldOfSoftware | Mark Zuckerberg is going to change the California sun for Miami. You have 11 billion reasons to do it.

Image | Wikimedia Commons (Lodovico Pogliaghi, Guillaume Rouille, Eugène Guillaume)