He did not study mathematics, nor did he enlist in the army: Elizebeth FriedmanShe simply fell in love with Shakespeare and that love embarked her on an adventure that led her to uncover Nazi spy networks in World War II, lock up Al Capone’s lackeys, and lay the foundations of the modern NSA.

This is the story of how, with the only help of a pencil and paper, a poet from the American Midwest became one of the most important cryptographers in the United States. It is also the story of how they hid their work and we forgot about it for decades.

Although she was the youngest of new siblings and grew up in a Quaker family in rural Illinois, Elizebeth graduated in English literature from Hillsdale College in Michigan. Almost immediately she began working as a teacher. That seemed like it would be his vocation until Shakespeare crossed his path again.

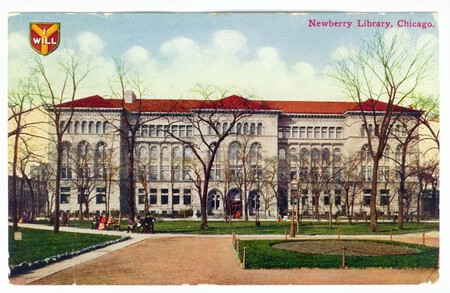

The Newberry, a Chicago research library, was looking for an assistant. It was nothing too striking except for the fact that, it was said, an original by the Stratford-upon-Avon playwright was kept in the library’s holdings. That was enough for Elizebeth.

It was there, working at Newberry, that he met George Fabyan, a millionaire convinced that Shakespeare’s works had been written by Francis Bacon. It is not a very strange belief, for centuries the confusing past of the English poet has generated rivers of ink about who William Shakespeare really was. What had not happened until then was that an eccentric billionaire decided to put his fortune at the service of the idea.

In 1916, at the age of 23, Elizebeth began working at Fabyan’s think tank, a private laboratory, Riverbank, where things as varied as genetic engineering or they worked on the development of weapons. Now, he would also have a team dedicated to finding the clues that Bacon ‘had left’ in works like ‘Hamlet’ or ‘Romeo and Juliet’.

That Riverbank was surely one of the first modern cryptography laboratories. There Elizebeth met her husband, William Friedman. Together, and unintentionally, they would shape modern American cryptography and play a very important role in the next 50 years of American defense.

‘We few, we happy few, we band of brothers’

It all started because, in the middle of the First World War, the army decided to turn to Riverbank to help them with code breaking. It was such a great success that the Secretary of War signed them and took the couple to Washington, DC.

Shortly after arriving, Elizebeth began working for the Treasury: the eighteenth amendment (the famous Prohibition) and alcohol trafficking networks were rampant throughout the United States. Elizebeth was terribly productive. It is estimated that, between 1926 and 1930, he deciphered an average of 20,000 smugglers’ messages a year, dismantling hundreds of ciphers in the process.

And the Second World War. The role of American cryptographers “was not very important”, but among them the Friedmans shined especially. Elizebeth’s skills were already known and served to dismantle a complex network of Nazi spies in Latin America that tried to promote fascist revolutions and weaken the “backyard” of the United States. Despite this, resources were very scarce and recognition even less.

Surely her most impressive work was that which led to the arrest and imprisonment of Velvalee Dickinson, the “doll woman”, a spy arrested in 1942 for passing all kinds of information to Japan (hidden in letters about patent leather dolls) during World War II.

“His abilities were so unusual that he became indispensable,” explained Jason Fagone, who has written a spectacular book about Friedman ‘The Woman who smashed codes’. “She was called on repeatedly to solve problems that no one else could solve. A secret weapon.” However, and despite the publicity of these cases, the Friedman surname did not transcend.

It was not an forgetfulness. Hoover, the famous and controversial director of the FBI, wiped the Friedmans off the map and awarded the merits of each of the cases to his Agency. Nothing surprising in a figure, that of Hoover, key in much of the American 20th century, capable of creating the largest research office in the world and, at the same time, using it as if it were his ‘private army’.

Although Elizebeth’s work and that of her husband were the seed of what would later become the NSA, their figure was forgotten, relegated and, until very few years ago, remained unrescued in the drawer of history. In 1999 he entered the NSA Hall of Fame and in 2002 a building was dedicated to him. He is another of those ‘hidden figures’ without whom we could not understand today’s world.

In WorldOfSoftware | In 1925, procrastination was already a problem and someone found the definitive solution: the isolation helmet.

In Xatka | Scotland remains almost a fiefdom in the 21st century: half of its land is owned by 421 owners