Someone might object to the term “eternal life” because this would be physically impossible in our universe: the Sun will one day engulf the Earth and the cosmos itself will stretch so much that matter itself will disintegrate. We are going to allow ourselves the luxury of talking about “eternal life” to refer to not dying from natural causes and thus be able to talk about other objections. Those that are done from ethics.

The debate has been reopened by Stephen Cave, a researcher at the Institute for Technology and Humanity, at the University of Cambridge. Cave has recently published his free ‘Should You Choose to Live Forever?‘ (which we could translate as ‘Would you choose to live forever?’).

In an interview published last week in the newspaper The Timesthe researcher outlined two of his arguments against this indefinite extension of eternal life. One ecological and the other social.

Cave argues that even relatively small advances in life expectancy could increase pressure on this planet’s resources. “If you think that the planet has reached its carrying capacity due to humans, or perhaps has already exceeded it (…), then this could be absolutely catastrophic,” explained the expert.

The second argument has to do with the possibility that any treatment that would allow us to extend our life indefinitely would not reach the entire population but only a small elite that could afford it. “We have this terrible scenario, of this incredibly rich and powerful gerontocracy, which watches generations of us ordinary people pass by like flies.”

They are two common reservations between those who consider themselves critically something that at first would seem like a wonderful idea. So much so that we can find in newspaper archives those who have postulated their counterarguments.

Against living forever

For example, in an article published in 2018 in The ConversationJohn Davis, professor of philosophy at California State University in Fullerton, is in favor of life extension, offering counterarguments to these considerations.

Davis instead debates the inequality argument, put forward before by thinkers such as John Harris, of the University of Manchester. For Davis, the fact that an advance cannot reach all of humanity is no reason why it cannot be taken advantage of by a few. The opposite would be, he explains, “equalizing ourselves downwards.”

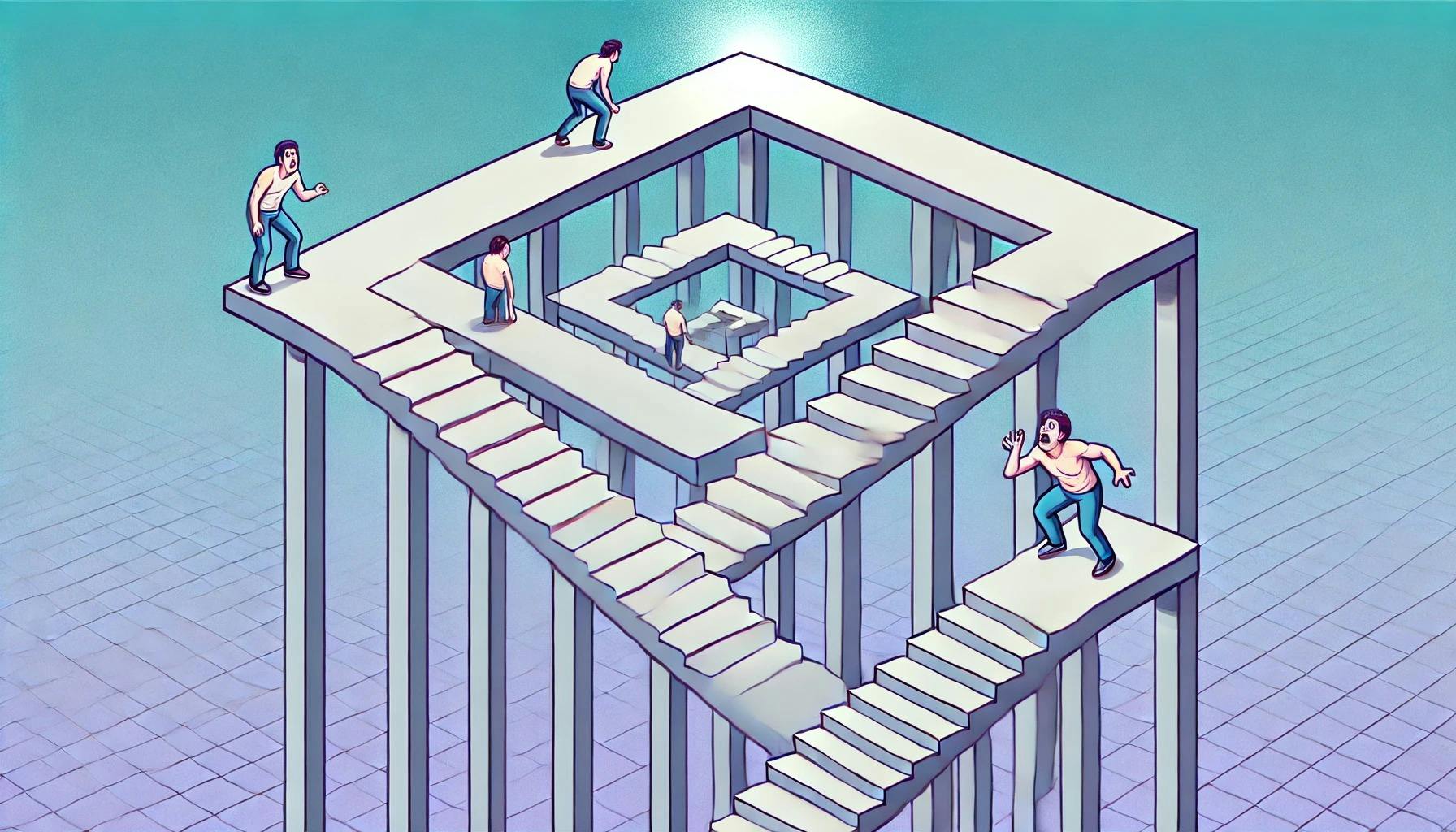

![]()

Regarding the environmental pressure argument, Davis argues that it would be possible to introduce measures such as control of birth rate to avoid overpopulation. This ban would be difficult to implement, he explains, “but trying to ban life extension would be equally difficult.”

Despite showing his disagreement with these two central arguments, Davis does admit that there would be problems derived from life extension: “dictators could live much longer than necessary, society would become too conservative and risk-averse, and pensions would have to be limited.”

Another advocate of extending life who draws attention to some ethical aspects to take into account is Brian Patrick Green, gerontological biologist and co-founder of the aging research center SENS. “There is nothing inherently wrong with extending healthy human lifespan, even to a large extent,” he explains.

However, he points out some of the arguments seen so far: ecological limits, justice and access, emergence of a risk-averse society immersed in “stasis”… Green also reminds us that, although human life is valuable in itself, for many it is not the ultimate “moral good”: many They are those who give their lives for other objectives, perhaps therefore there are other priorities.

This is an issue that has been of interest to philosophers and scientists for some time. In 2007, researchers Martien Pijnenburg and Carlo Leget, from Radboud University in the Netherlands, wrote an article in the journal Journal of Medical Ethics in which they also showed an unfavorable position regarding living forever.

The authors base themselves on three arguments, starting with that of justice. The second is that of the relational dimension: a critique of the “individualistic” dimension of life extension. The third has to do with the search for fulfillment, for the “meaning of life,” a search that could be affected for those who live life without waiting for its end.

The criticism of “individualism” serves as a reminder that this is a debate that overlaps with othersperhaps more current, such as that of euthanasia. As Davis argues in his own article, in a world of longevity, would we be morally or legally obligated to extend our lives? For many, the answer may depend on something as variable as how we ask the question.

Regardless of the negative considerations that may be raised, the scientific struggle to achieve “eternal life” continues, and much of the funding that fuels the research machinery comes from large donors.

Cave pointed out in his interview that scientific research often generates complementary benefits. It is possible that one day these advances will translate into small improvements in the hope and quality of life of the rest. Perhaps in science the spillover effect is more than a myth. We will have to wait, how much time we still have left.

In WorldOfSoftware | What will the world be like when those of us who have not turned 40 live to be 100 years old?

In WorldOfSoftware | If the question is how to reactivate birth rates, China believes it has the answer: finance painless births

Image | Matteo Vistocco

*An earlier version of this article was published in December 2023

*Due to a technical error, the author of this article appears as Andrés P. Mohorte. Actually its author is Pablo Martínez-Juárez