The train is the backbone of many countries. In Europe we know it well, in Latin America they are catching up and today’s China and Japan would not understand each other without it. Another country where it is vital is Australia, although more than for the movement of the population, for the transport of goods. And, in 2001, in the heart of Western Australia, the BHP Iron Ore made history by becoming the longest train in the world.

More than seven kilometers long that have not yet been equaled.

Necessary. One of the most powerful industries in Australia is mining, so much so that there are even mining influencers who recruit workers from any country. In the late 90s, mining companies faced a challenge: an increasing amount of mineral had to be transported from the source to the export ports. It was a challenge because logistics costs had to be kept under control so that prices did not skyrocket.

Traditionally, we would have chosen to put more trains into operation, but it would not be efficient because we would have to pay for more fuel, for the use of the infrastructure and the salaries of a larger crew. BHP, the Australian giant that is one of the largest mining companies in the world, comes into play with an idea: what if we set up a huge train to load iron? This is how the Iron Ore train was born.

The BHP Iron Ore train. Its dimensions were extraordinary: a convoy made up of 682 wagons, 5,648 wheels, a loaded weight of almost 100,000 tons and a length of 7,353 kilometers. Imagine 22 Eiffel Towers lying down and aligned, like this. To pull such a monster, eight GE AC6000CW locomotives (each with 6,000 HP) with 16-cylinder engines were distributed along the vehicle.

Apart from the front, the rest were within a kilometer of each other and managed to complete a 275 kilometer Yandi journey, with a cargo of Newman mines, to Port Hedland in just ten hours. The pace was slow, yes, but the important thing about this was not the Guinness record it achieved, but the test of a technology called Distributed Power.

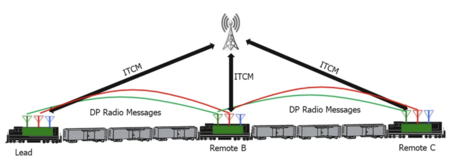

Distributed Power. This was BHP’s goal, to prove that the technology worked. And it basically consists of what we have said: distributing the locomotives along the train instead of concentrating them in the front so that the traction and braking force is greater, more uniform and, also, more efficient. Everything worked like a Swiss clock thanks to great precision and harmony between the locomotives, which were controlled by a single driver in the front system.

It’s long, and there’s no train

If Distributed Power was the technology, the control system was LOCOTROL. The leading locomotive communicated with the remote ones through a radio frequency system that synchronized all acceleration and braking operations. This allowed lateral forces and friction to be drastically reduced when cornering, which reduced both wheel wear and the risk of derailment and, in turn, it is estimated that between 4 and 6% less fuel was consumed.

Pilbara. The BHP Iron Ore was a technical prodigy that set the record for the longest train in the world in 2001, but if you are a train enthusiast, don’t pack your bags yet to see it in action: it was a one-time event, so much so that there is very little material about it. Once the technology was proven, what BHP did was apply it to smaller trains.

The Pilbara is the region in which much of its operations are concentrated, and what the company currently operates are several regular trains with formations of about four locomotives with about 270 carriages. It is still impressive, since the length of these trains is close to three kilometers and they have a loaded weight of about 40,000 tons.

The company’s next steps are to electrify these trains to reduce emissions, and one trick will be to use regenerative braking to recharge the batteries in sloped areas. It is something that other companies are also testing in the country.

Similar attempts. Thus, the BHP Iron Ore was a prodigy, but also something unique that has not been matched, not even close, more than 20 years after its launch for that test. In August this year, Indian Railways put into operation the Rudrastra, a 354-car, 4.5-kilometer-long train powered by seven locomotives (two at the front and one every 59 cars). And in Europe, tests are also being carried out with distributed power trains, but for kilometer and a half trains.

In the end, they are all very far from the Iron Ore both in length and weight, but beyond the record in 2001 it was shown that this distributed power technology was a solution for trains longer than conventional ones. We’ll see if at some point someone needs to create a longer train, but it seems complicated.

Images | Wabtec, BHP

In WorldOfSoftware | The longest train journey in the world: more than 18,000 kilometers between Portugal and Singapore without changing transport