Spain has a problem with housing. That is an (almost) objective fact. The CIS says it, which places it as the great concern of the Spanish people, but a quick review of the newspaper archive comes to confirm it. In recent months, few topics have generated more political debate or brought as many people onto the streets as the difficulties in accessing a home. What is no longer so clear is how to solve this residential “crisis” recognized by the Government itself.

Should we build more houses? Does Spain suffer from a housing deficit? Do we need more land to build? Usually the answer to those three questions is a strong ‘yes’. Now a new study signed by two professors from the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) and published in a magazine linked to the Ministry of Housing indicates that perhaps we were wrong.

What has happened? That two professors from the Higher Technical School of Architecture of Barcelona (ETSAB), Blanca Arellano-Ramos and Josep Roca-Cladera, have published a study on the problems that Spain is facing in terms of housing. The report in question is titled ‘Five theses about housing policy in Spain’ and is included in a monograph of CyTETa magazine published by the Ministry of Housing. So far nothing exceptional.

The curious thing is that the text questions many of the ideas rooted in the real estate sector, such as that our country suffers from a housing deficit or needs more land to build. While the Bank of Spain (BE) estimates the imbalance between supply and demand at 700,000 homes, the study questions whether there really is a ‘hole’ in the market or whether prices will fall if we build more.

Is there a housing deficit? As already indicated in its title, the article is structured around five theses. And the first addresses precisely that point: Does Spain suffer from a housing deficit? The question is interesting because it is one of the most deeply rooted ideas in the sector. The Bank of Spain itself has calculated that 700,000 houses would be needed to cover residential demand.

For Arellano-Ramos and Roca-Cladera the reality is quite different. In his opinion, one cannot talk about a deficit without first taking into account the excess of housing accumulated between 2011 and 2021 and the stock of vacant properties.

The researchers remember that between 2011 and 2021 the housing stock exceeded the growth in the number of homes by 959,554 units, generating a considerable pocket. In fact, they assure that in 2021 the “accumulated excess” was close to 8.1 million properties, a “‘cushion’ more than enough to absorb temporary housing deficits such as those produced during the 2021-2024 period,” recalls the UPC in the statement in which it reports on the study.

What does that mean? That for researchers it is not so obvious that Spain suffers from a shortage of new housing. In their analysis they also remember that a good part of the excess of houses and apartments corresponds to second homes and empty homes. The INE itself estimates that at least in 2021 there were 3.84 million uninhabited properties, 14.4% of the real estate stock.

This percentage far exceeds what most experts consider “desirable” (5%), but at least the UPC statement does not address another fundamental aspect: the distribution of these wasted properties, if they are located in stressed markets, such as Madrid, Barcelona or Malaga, or in areas where demand is minimal or even non-existent, in the case of emptied Spain.

What if we build more? That is the second question the researchers address. What if we build more homes? Would prices be reduced? Their response is once again skeptical to say the least: increasing buildings will not lead to greater social equity nor will it serve to soften prices.

“On the contrary,” the UPC note slips. “According to the authors of the study, the solution is not to build more new homes so that the laws of the market balance prices. In addition to having serious environmental effects, what favors is the real estate bubble like the one that occurred around 2000.”

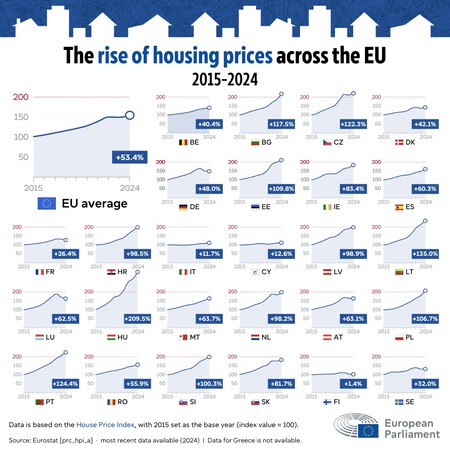

What happens in other neighboring countries? Among other arguments, Arellano-Ramos and Roca-Cladera recall that the rise in prices is not a problem exclusive to the Spanish market, but rather something widespread on the continent. So the question is obvious: if the increase in prices is due to the imbalance between supply and demand, do the majority of EU countries share that same problem?

“Is there simultaneously a restriction of supply in relation to demand occurring throughout Europe in relation to demand that explains the increase in residential prices? It does not seem that this is plausible. Therefore it is not reasonable, prima facieturning to the low construction of new housing as the main cause of housing prices”, the authors reflect before remembering that Spain has invested a higher percentage of GDP in construction than the European average.

Do we need more land? The researchers also question whether in Spain the problem of lack of accessibility to housing can be explained by the scarcity of land. And to prove it, they go to the newspaper archive: between the late 90s and the early 2000s, buildable land was made available in the country, which allowed for “massive construction” of residential housing. This boom was not accompanied, however, by a reduction in the Price of the square meter. Quite the opposite: residential prices increased, as in other parts of Europe.

If Spain saw housing prices rise between 1996 and 2008, it was not because there was no land on which to build or build new homes. “Spain became more urbanized than ever and the result did not represent a reduction in prices, on the contrary,” underlines the UPC in its statement, which recalls that between 2000 and 2012 Spain was the European country with the greatest “consumption” of land: more than 2,400 square kilometers (km2), almost as much as France and Germany combined and more than what Poland, Italy and the United Kingdom added during that same period.

Buy a house alone” width=”375″ height=”142″ src=”https://i.blogs.es/e77fa8/photo-1759401389425-77e3c4592ba0/375_142.jpeg”/>

And what is the solution? The study dedicates its fourth and fifth sections to this, to propose solutions for the residential crisis that (there is unanimous consensus on this) Spain is suffering. The researchers’ recipe is clear: the country needs to work on accessibility, which involves building more social housing.

According to UPC researchers, Spain suffers a deficit in this type of construction, which during the first months of 2024 did not represent even 8% of total property transfers. There has been a legislative effort to reverse that situation, true; But in the opinion of experts, the construction of protected housing has continued to remain at “insufficient levels.”

“The direct benefits are diverse, by facilitating access to the housing market for the most disadvantaged sectors. Correlatedly, it facilitates the emancipation of young people and helps vulnerable groups meet their housing needs,” claim Arellano-Ramos and Roca-Cladera. Its analysis of prices from 2004 to 2023 has in fact confirmed that reserving land for VPO has helped to “moderate” prices on the free market. “It is urgent to take a step forward in terms of promoting the construction of protected housing on urban land.”

That’s all? No. The researchers also advocate boosting rents and point out the “convenience” of regulating prices in those areas considered stressed. According to their analysis, there is no evidence that such a measure reduces supply, but rather there are other factors that stress the market, such as seasonal rentals or tourist and empty apartments.

Images | Gab Audiovisuel (Unsplash) and European Parliament

In WorldOfSoftware | The housing market is so broken that it has found an unlikely place for express purchases: Telegram