January 8, 2025 • 10:13 am ET

What’s behind Egypt and China’s ‘golden decade’ of partnership

The beginning of 2025 marked the end of the “Year of the Egyptian-Chinese Partnership” and closed out the “golden decade”: A ten-year period during which Egypt and China grew their bilateral relationship as part of their efforts to deepen their comprehensive strategic partnership. Given the trajectory of the relationship over the past ten years, expect to see a larger Chinese presence in Egypt—a country that has long been one of the United States’ most important allies in the Middle East.

The 2024 partnership year ended with Egyptian Foreign Minister Badr Abdelatty visiting Beijing on December 13 for a meeting with his counterpart, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi. This came shortly after Egyptian Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly’s visit to Beijing in September to attend the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. While there, a delegation from the Suez Canal Economic Zone (SCZone) signed one billion dollars’ worth of contracts and memoranda of understanding with Chinese companies.

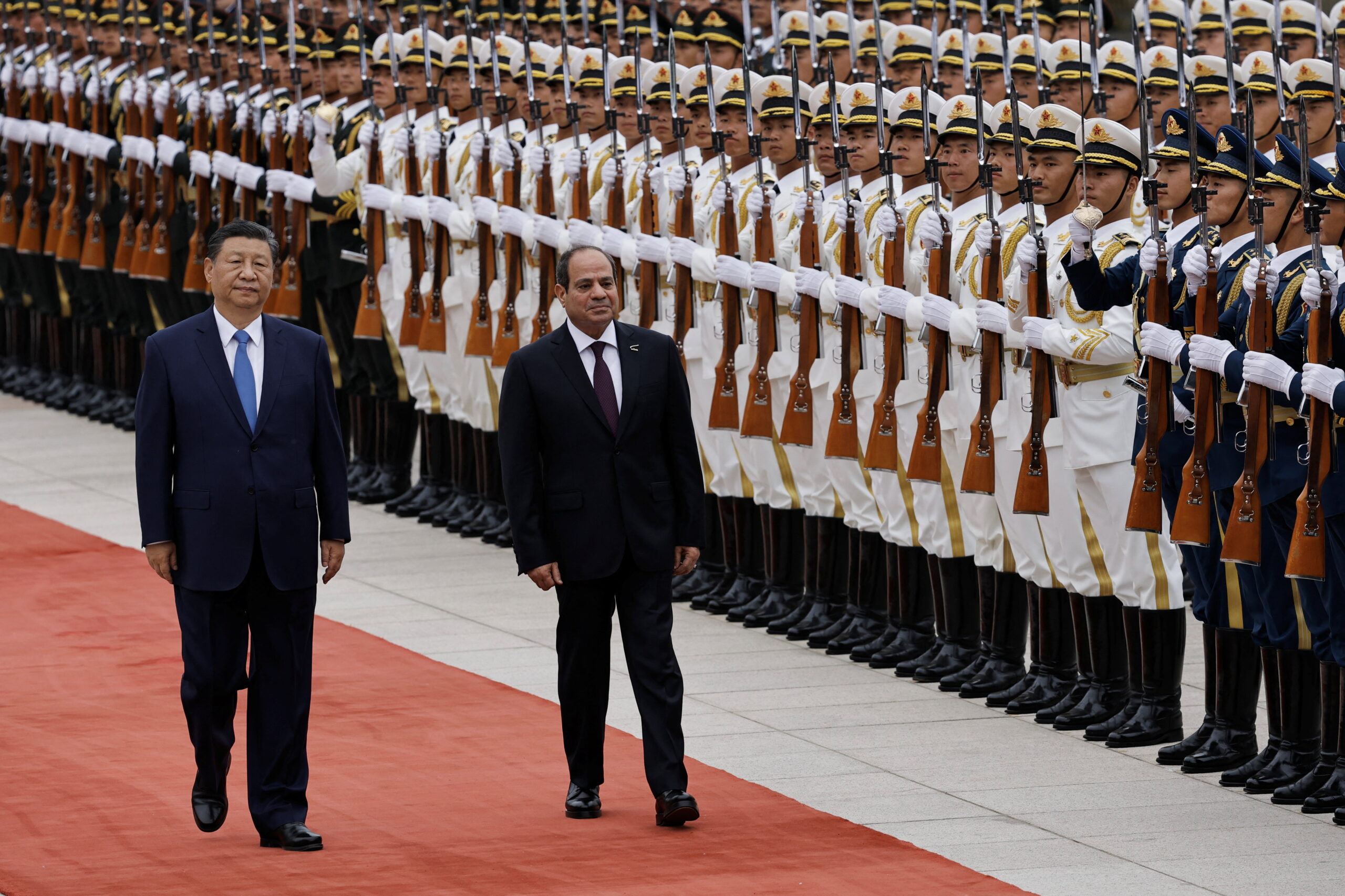

The most significant visit of the year, however, was from Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi in May, when he was in Beijing for the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum as well as a China-Egypt summit. During the summit, Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Sisi discussed deeper cooperation in information and communications technology, artificial intelligence, renewable energy, food security, finance, and cultural exchanges, demonstrating how broad the relationship has become.

This was Sisi’s eighth visit to China since becoming president in 2014. For comparison’s sake, former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak went to China six times during his thirty years in office. This shift under Sisi—this “golden decade”—is an outlier in China-Egypt relations; there has never been so much engagement between the two. From the China side, this can partly be explained by a surge in international partnerships after the Belt and Road Initiative was announced in 2013. Since then, China has established some form of partnership agreement with nearly every country in the Middle East and North Africa (except Lebanon, Sudan, and Yemen).

It is also a reflection of a more robust Chinese presence in the Middle East in general, as the region assumes an increasingly important role in China’s energy security, trade, and contracting. In 2014 Xi outlined a “1+2+3” cooperation framework for developing ties with Arab countries, focusing on energy cooperation, trade and infrastructure construction, and renewable energy and high tech. In 2016 China released its first ever Arab Policy Paper. China’s outreach to Egypt has not happened in a vacuum but rather as part of a larger strategy to make Beijing a more important actor in the Middle East and North Africa.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

For Egypt, the motivation for closer ties to China can likely be explained by a combination of political and economic necessity. Before taking office, Sisi—in an interview with the Washington Post—complained about the United States: “You left the Egyptians. You turned your back on the Egyptians, and they won’t forget that.” Resentment over the Obama administration’s abandonment of Mubarak during the Arab Spring in February 2011 convinced many in Cairo that the United States was a less reliable partner, making a broader set of extra-regional relationships an important means of support for a government on shaky ground.

That this coincided with China’s regional ambitions made Beijing look like a good bet: It’s not easy to find a great-power partner with deep pockets and no interest in Egypt’s domestic politics. As one Egyptian told the Financial Times in 2018, “there are economic powers who have the ability to help us but not the desire, and others who have the desire but not the ability . . . China tops the list of those who have both the ability and the desire.”

Over the course of the “golden decade,” China has consistently ranked as Egypt’s top trade partner, Chinese companies have tendered several major contracts, and there has been a rise in investment, and with it, jobs for Egyptians.

Much of this has been centered on Egypt’s ports, especially the SCZone, which was expanded in 2016 with investment from TEDA Investment Holding Co., a state-owned enterprise based in Tianjin. Within this area is the China-Egypt Suez Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone, an industrial park where over 160 Chinese companies operate, providing over seventy thousand jobs for Egyptians. Throughout the SCZone, China’s presence is growing; SCZone Chairman Walid Gamal El-Din said in December 2024 that Chinese investment there had reached three billion dollars and accounts for 40 percent of foreign direct investment over the past two years.

This is important given the state of Egypt’s economy. Inflation was at 25.5 percent in November. Egypt’s revenues from the Suez Canal were down by 60 percent last year as a result of Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping. Before making a $35-billion deal with the United Arab Emirates last February and then receiving an eight-billion-dollar loan from the International Monetary Fund last March, Egypt’s economy was facing a looming crisis. In this context, a strong partnership with the world’s second-largest economy is significant for a government without a lot of good options.

Look closer though, and it appears to be less of a partnership and more of an asymmetrical relationship that tilts heavily in China’s favor. The trade numbers are telling. In 2022, volume of trade was just over $13.2 billion. However, of that total, Chinese exports were valued at just under $11.5 billion, while Egyptian exports to China were $1.8 billion. This imbalance was not an anomaly. In fact, it was the most favorable year for Egypt throughout the decade. In 2023, Egyptian exports to China plummeted to $834 million.

The type of trade is troubling too. Egyptian exports to China are almost all commodities, and of that, the majority is consistently energy. This trend has not improved throughout the “golden decade”: In 2014, 31 percent of Egypt’s exports to China were energy, and in 2022, energy made up 56 percent. Since China has said that it aims to reach a peak in its carbon emissions by 2030 and that it plans to be carbon neutral by 2060, Cairo needs to find something else to sell to its top trade partner.

Looking at other indicators of economic engagement since the comprehensive strategic partnership was announced is equally interesting. From 2005 to 2013, Chinese companies earned $3.34 billion from contracts in Egypt. In the decade since, that jumped to $16.62 billion. Clearly, the comprehensive strategic partnership has been a bonanza for Chinese companies.

Beyond the economic side of the relationship, defense cooperation was also on the rise in 2024, albeit from a very low starting point. The two held a joint naval exercise in the Mediterranean Sea in August, training in communications coordination, formation maneuvering, and maritime replenishment positioning. This was the first joint exercise since 2019, when they trained on counterterrorism and piracy, transportation signaling exercises, and several sailing formations. In late August 2024, the Chinese Air Force sent eight planes to an Egyptian air show.

Most interesting was a persistent rumor that Egypt would purchase Chinese J-10C fighter jets as replacements for their aging F-16s, a move one analyst explained as Egypt “diversifying its military suppliers to reduce reliance on the West, particularly the US.” Another analyst said that the move is likely Egypt’s attempt to secure a bargaining chip after the United States froze a deal regarding twenty F-35s which US President Donald Trump verbally committed to sell to Egypt in 2018. Another opinion is that the J-10C, costing between forty to fifty million dollars, is a much more cost-effective option for Egypt.

Whatever the case, the sale remains unconfirmed and there are several reasons why it may not materialize. For one, the J-10C is a fourth-generation jet and the Egyptian air force wants fifth generation. Fourth generation jets don’t address Egypt’s need for aerial superiority to secure the gas field in its exclusive economic zone in the eastern Mediterranean, and they don’t address its concerns with Ethiopia.

Most importantly, purchasing Chinese fighter jets would likely affect the Foreign Military Financing that Egypt gets from the United States—financing that must be approved by the US Congress. In 2024 this totaled $1.3 billion. In an era of US-China competition, Washington would not look favorably on Egypt bringing Chinese fighter jets into its air force. At this point, the J-10C rumor looks like an attempt to trigger the United States’ competitive instinct, but with Trump’s upcoming return to the White House, Cairo might see a path to the long-coveted F-35s.

At the start of Sisi’s decade in power, the China relationship looked like the best option available to a government without a lot of options. Since then, it has become a more serious partnership. China’s power and influence in the Middle East has increased and Egypt has emerged as a useful partner. At the same time, when I ask Egyptians about China, they do not describe the relationship as comprehensive or strategic—they call it transactional. Few see China as a country with the willingness or capacity to play a leading role in the Middle East. If the coming decade follows the same pattern as the previous one, however, China could be a much more influential actor in Cairo, making a much more complex Middle East for US diplomacy.

Jonathan Fulton is a nonresident senior fellow for ’s Middle East Programs and the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative and an associate professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi.

Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi review the honour guard during a welcome ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China May 29, 2024. REUTERS/Tingshu Wang/Pool

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25824245/Gg1_aHrWcAAkRXE.jpeg)