Authors:

(1) Diwen Xue, University of Michigan;

(2) Reethika Ramesh, University of Michigan;

(3) Arham Jain, University of Michigan;

(4) Arham Jain, Merit Network, Inc.;

(5) J. Alex Halderman, University of Michigan;

(6) Jedidiah R. Crandall, Arizona State University/Breakpointing Bad;

(7) Roya Ensaf, University of Michigan.

Table of Links

Abstract and 1 Introduction

2 Background & Related Work

3 Challenges in Real-world VPN Detection

4 Adversary Model and Deployment

5 Ethics, Privacy, and Responsible Disclosure

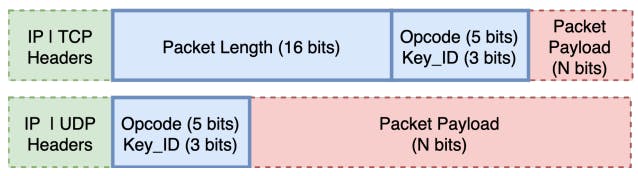

6 Identifying Fingerprintable Features and 6.1 Opcode-based Fingerprinting

6.2 ACK-based Fingerprinting

6.3 Active Server Fingerprinting

6.4 Constructing Filters and Probers

7 Fine-tuning for Deployment and 7.1 ACK Fingerprint Thresholds

7.2 Choice of Observation Window N

7.3 Effects of Packet Loss

7.4 Server Churn for Asynchronous Probing

7.5 Probe UDP and Obfuscated OpenVPN Servers

8 Real-world Deployment Setup

9 Evaluation & Findings and 9.1 Results for control VPN flows

9.2 Results for all flows

10 Discussion and Mitigations

11 Conclusion

12 Acknowledgement and References

Appendix

5 Ethics, Privacy, and Responsible Disclosure

Raw network traffic that contains real users’ data is highly sensitive, and this is especially true for traffic related to privacy oriented services such as VPNs. Here we describe how we consider the security and privacy risks and ethical issues raised by our work, and we detail the procedural and technical steps we take to mitigate the risks.

Foremost among the ethical concerns associated with this work is our Filter deployment inside Merit’s network to analyze user traffic. Merit, which has extensive previous experience collaborating with universities and has well-defined ethics and privacy rules to govern such projects, supervised the deployment. We also cleared our research plan with our university legal counsel and IRB. Although the IRB determined that the work is not regulated, we take extensive measures to minimize potential risks for end-users.

Our framework is fine-tuned on both real and lab-generated traffic data, and it is evaluated on live ISP traffic. For controlled fine-tuning, a small traffic snapshot (the ISP Dataset in section 7) was used to calibrate parameters, e.g., the size of observation window. The traffic snapshot, sampling 1/30 of all flows for 45 minutes on July 28, 2021, was generated and analyzed entirely on Merit systems, with security mechanisms limiting access to select members of the team. As with the design described in Section 6, Filter analyzed only the first payload byte, completely ignoring the remainder of the payload, and it recorded only the observed degree of variation. The raw snapshot was never inspected by humans and was deleted after the fine-tuning concluded.

For deployment and evaluation on live ISP traffic, the Filter architecture is designed to minimize risks of disrupting or modifying user traffic. The Monitoring Station only receives a copy of the traffic, so even if our software were to malfunction, network service would be unaffected. In addition, to reduce privacy risks, the Filter collects only the minimum information necessary for the subsequent probing operation. It records only the server IP addresses and ports of matching connections, which are bucketed into 5-minute internals to inhibit time correlation. These logs are stored and analyzed on a server that is securely maintained by Merit and is accessible only to a few members of our research team on a least-privilege basis. Merit reviewed our source code prior to deploying it on their network. During deployment and evaluation, no packet payloads or client IP addresses are ever recorded to disk or inspected by humans.

Based on the Filter log, the Probers send probes to candidate VPN servers. To minimize the risk of disrupting server operations, we design the probes to be non-invasive and make

information available to assist operators in debugging any problems we inadvertently cause. Each server receives only 2– 10 innocuous connection attempts, similar to those commonly used in Internet measurement tools like Nmap. The probes originate from two dedicated machines that we provisioned with web pages that explain the nature of the experiment and provide our contact information. We did not receive any inquiries, complaints, or problem reports. Since the server IP addresses themselves may sometimes be non-public, we only report aggregate statistics (e.g., the false positive rate) and will not publish any of the addresses that we collect. Any data requests will be referred to Merit.

As with all attack-oriented research, there is a risk that our work developing VPN fingerprinting techniques will be adopted by real attackers. To minimize this risk, we are in the process of responsibly disclosing our findings to the VPN operators whose obfuscated servers we successfully identified in our evaluation. We believe that the security of the VPN ecosystem is best advanced by having these problems surfaced by responsible researchers. Our work will help accurately inform users about the VPN services they rely on, and we hope it will enable more robust countermeasures to be developed and deployed.