ANDREA BARTZ, CHARLES GRAEBER, and KIRK WALLACE JOHNSON v. ANTHROPIC PBC, retrieved on June 25, 2025, is part of

B. THE COPIES USED TO BUILD A CENTRAL LIBRARY

Recall that Anthropic purchased millions of print books for its central library and pirated millions of digital books for its central library, too. It used specific sets and subsets of books for training specific LLMs. And, it then retained all the copies in its central library for other uses that might arise even after deciding it would not use them to train any LLM (at all or ever again). Anthropic seems to believe that because some of the works it copied were sometimes used in training LLMs, Anthropic was entitled to take for free all the works in the world and keep them forever with no further accounting. There is no carveout, however, from the Copyright Act for AI companies.

Because the legal issues differ between the library copies Anthropic purchased and pirated, this order takes them in turn.

(i) The Purchased Library Copies Converted from Print to Digital

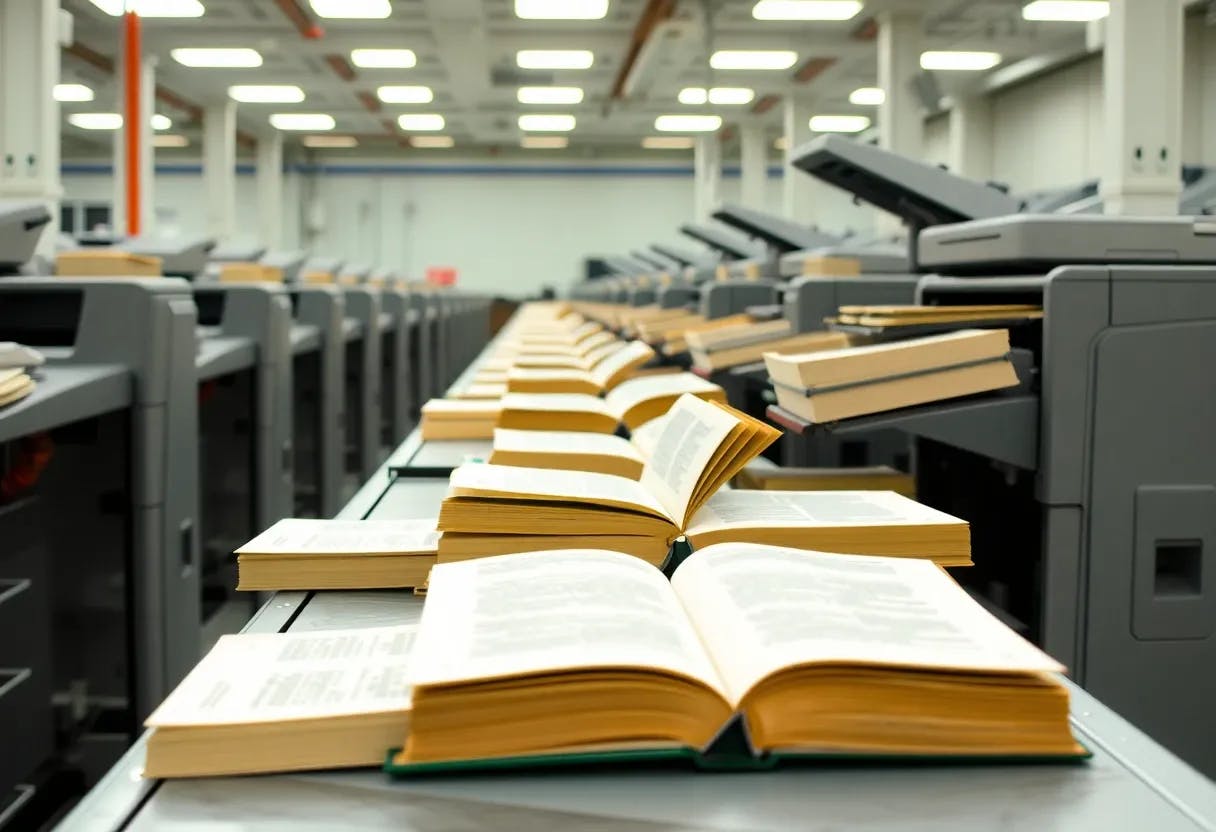

Anthropic purchased millions of print copies to “build a research library” (Opp. Exh. 22 at 145, 148). It destroyed each print copy while replacing it with a digital copy for use in its library (not for sharing nor sale outside the company). As to these copies, Authors do not complain that Anthropic failed to pay to acquire a library copy. Authors only complain that Anthropic changed each copy’s format from print to digital (see Opp. 15, 25 & n.14). On the facts here, that format change itself added no new copies, eased storage and enabled searchability, and was not done for purposes trenching upon the copyright owner’s rightful interests — it was transformative.

Anthropic purchased its print copies fair and square. With each purchase came entitlement for Anthropic to “dispose[ ]” each copy as it saw fit. 17 U.S.C. § 109(a). So, Anthropic was entitled to keep the copies in its central library for all the ordinary uses. Yes, Anthropic changed the format of these library copies from print to digital — giving rise to the issue here.

All agree on the facts of the format change. Anthropic “destructively scan[ned]” the print copies to create the digital ones. Anthropic or its vendors stripped the bindings from the print books, cut the pages to workable dimensions, and scanned those pages — discarding each print copy while creating a digital one in its place. The digital copy was then housed in the “research library” or “generalized data area” in place of the print copy (Opp. Exh. 22 at 145– 46, 193–94). Authors do not allege and our record does not show that Anthropic provided its converted digital copies of print books to anyone outside Anthropic.

The parties disagree about the legal consequences of the format change. Was scanning the print copies to create digital replacements transformative? Anthropic argues it was because it was reasonably necessary to training LLMs. Authors argue it was a distinguishable step requiring independent justification.

Here, for reasons narrower than Anthropic offers, the mere format change was a fair use.

Storage and searchability are not creative properties of the copyrighted work itself but physical properties of the frame around the work or informational properties about the work. See Texaco, 802 F. Supp. at 14 (physical), aff’d, 60 F.3d at 919; Google, 804 F.3d at 225 (informational); Sony Corp. of Am. v. Universal City Studios, Inc. (“Sony Betamax”), 464 U.S. 417, 447 (1984) (rightful interests). In Texaco, the court reasoned that if a purchased scientific journal article had been copied “onto microfilm to conserve space, this might [have been] a persuasive transformative use.” 802 F. Supp. at 14 (Judge Pierre Leval), aff’d, 60 F.3d at 919 (reducing “bulk[ ]” “might suffice to tilt the first fair use factor in favor of Texaco if these purposes were dominant“). In Google Books, the court reasoned that a print-to-digital change to expose information about the work was transformative. Google, 804 F.3d at 225 (Judge Pierre Leval). And, in Sony Betamax, the Supreme Court held that making a recording of a television show in order to instead watch it at a later time was copying but did not usurp any rightful interest of the copyright owner. 464 U.S. at 447, 455. Important to the Supreme Court’s reasoning was the expectation that most such copiers would not distribute the permanent copies of the work. Finally, in A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc., our court of appeals recognized the reasoning just explained, and therefore rejected by contrast a digitization effort that was touted as space-shifting but in fact resulted in the multiplication of copies shared with outsiders through a file-sharing service. 239 F.3d 1004, 1019 (9th Cir. 2001), aff’g in this part 114 F. Supp. 2d 896, 912–13, 915–16 (N.D. Cal. 2000) (Judge Marilyn Hall Patel) (citing Sony Betamax and Texaco).

Here, every purchased print copy was copied in order to save storage space and to enable searchability as a digital copy. The print original was destroyed. One replaced the other. And, there is no evidence that the new, digital copy was shown, shared, or sold outside the company. This use was even more clearly transformative than those in Texaco, Google, and Sony Betamax (where the number of copies went up by at least one), and, of course, more transformative than those uses rejected in Napster (where the number went up by “millions” of copies shared for free with others).

Yes, Anthropic is a commercial outfit. And, this order takes for granted that Anthropic in fact benefited from the print-to-digital format change — or it would not have gone to all the trouble. But the crux of the first fair use factor’s concern for “commercial” use is in protecting the copyright owners and their entitlements to exploit their copyright as they see fit (or not). See, e.g., Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enters., 471 U.S. 539, 562 (1985). That the accused is a commercial entity is indicative, not dispositive. That the accused stands to benefit is likewise indicative. But what matters most is whether the format change exploits anything the Copyright Act reserves to the copyright owner. Anthropic already had purchased permanent library copies (print ones). It did not create new copies to share or sell outside.

Yes, Authors also might have wished to charge Anthropic more for digital than for print copies. And, this order takes for granted that Authors could have succeeded if Anthropic had been barred from the format change. “But the Constitution’s language [in Clause 8] nowhere suggests that [the copyright owner’s] limited exclusive right should include a right to divide markets or a concomitant right to charge different purchasers different prices for the same book, [merely] say to increase or to maximize gain.” See Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 568 U.S. 519, 552 (2013); see also U.S. CONST. art. I., § 8, cl. 8. Nor does the Copyright Act itself. Section 106 sets out exclusive rights that fair uses under Section 107 abridge. Section 106(1) reserves to the copyright owner the right to make reproductions. But on our facts we face the unusual situation where one copy entirely replaced the another. And, Section 106(2) reserves to the copyright owner the right to make derivative works that add or subtract creative material — as occurs in a “translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, [or] condensation” of a book, 17 U.S.C. § 101 (definitions). For some “other modification[ ]” of a book to constitute a “derivative work,” it must itself “represent an original work of authorship.” Ibid. But on our facts the format was changed but no content was added or subtracted. See Mirage Editions, Inc. v. Albuquerque A.R.T. Co., 856 F.2d 1341, 1342, 1343– 44 (9th Cir. 1988) (yes where elements added to create new decorative ceramic) (4).

Section 106(3) further reserves to the copyright owner the right to distribute copies. But again, the replacement copy here was kept in the central library, not distributed. Cf. Fox News Network, LLC v. TVEyes, Inc., 883 F.3d 169, 176–78 (2d Cir. 2018) (enabling searching for “information about the material” can be transformative use, even if some distribution results); Lewis Galoob Toys, Inc. v. Nintendo of Am., Inc., 964 F.2d 965, 968, 971 (9th Cir. 1992) (using nifty converter to “merely enhance[ ]” audiovisual displays emitted from purchased videogame cartridge was fair use of those displays partly because no surplus copies of cartridge or displays were ever created).

As a result, Anthropic’s format-change from print library copies to digital library copies was transformative under fair use factor one. Anthropic was entitled to retain a copy of these works in a print format. It retained them instead in a digital format, easing storage and searchability. And, the further copies made therefrom for purposes of training LLMs were themselves transformative for that further reason, as above.

To be clear, this print-to-digital conversion involved a different and narrower form of transformative use than the broader one advanced by Anthropic. Anthropic argues that the central library use was part and parcel of the LLM training use and therefore transformative. This order disagrees. However, this order holds that the mere conversion of a print book to a digital file to save space and enable searchability was transformative for that reason alone. Therefore, the digital copy should be treated just as if the purchased print copy had been placed in the central library.

In sum, the first fair use factor favors fair use for the digital library copies converted from purchased print library copies — but these do not excuse the pirated library copies.

(4) Even if print-to-digital format change did infringe the right to prepare derivative works, Authors have conceded that “Plaintiffs’ infringement claims are predicated on Anthropic’s unauthorized reproduction (17 U.S.C. § 106(1)); Plaintiffs are not alleging infringement by Anthropic of any right to prepare derivative works (id. at § 106(2))” (Dkt. No. 203 at 2 (citations original)). Whether this concession had consequence for copies tokenized and used for training or “compressed” into the trained LLMs is not reached by this order because Anthropic does not rely on Authors’ concession and those copies were here used transformatively.

About HackerNoon Legal PDF Series: We bring you the most important technical and insightful public domain court case filings.

This court case retrieved on June 25, 2025, from storage.courtlistener.com, is part of the public domain. The court-created documents are works of the federal government, and under copyright law, are automatically placed in the public domain and may be shared without legal restriction.