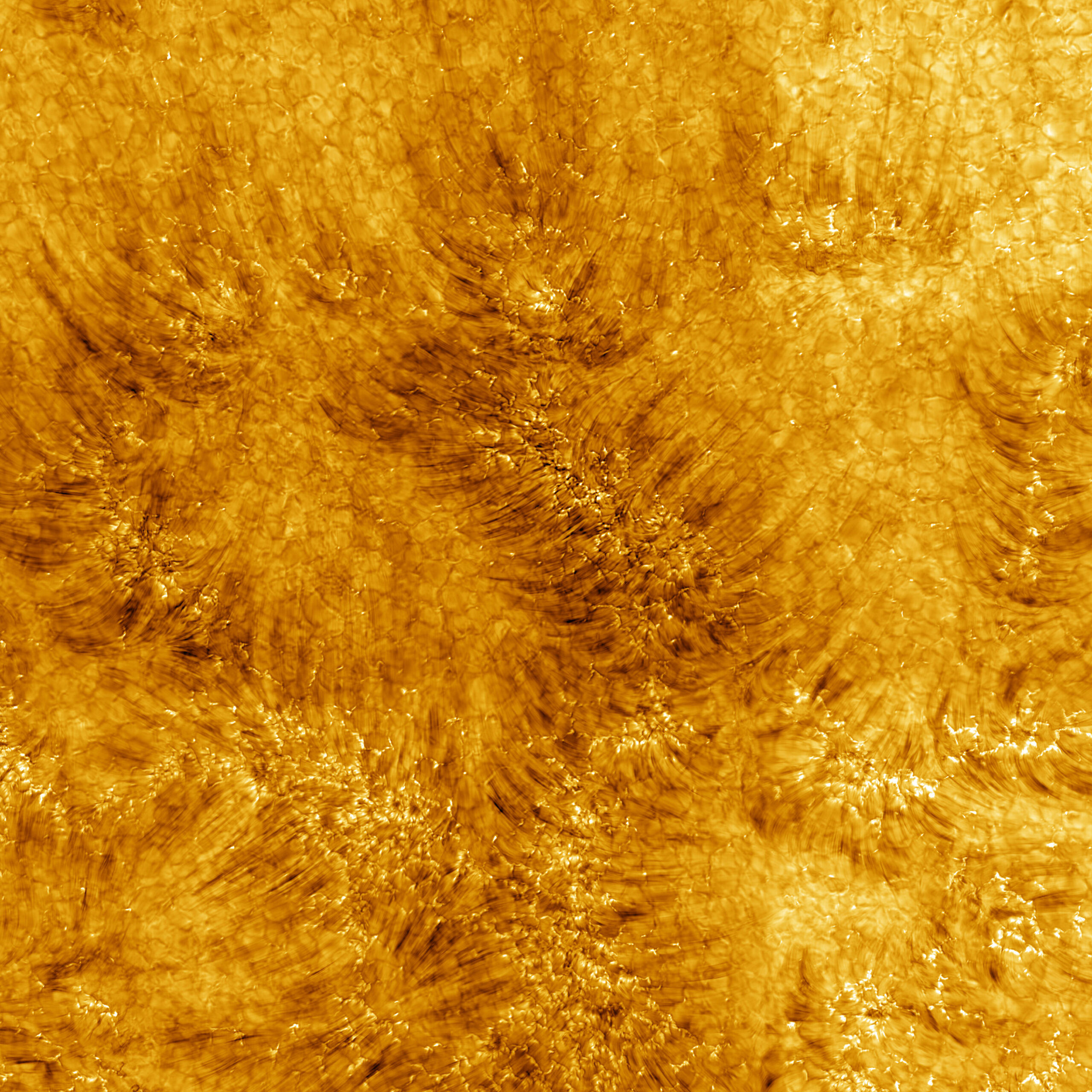

NASA has been slowly working the Parker Solar Probe closer and closer to the Sun ever since its launch in 2018. The probe, which is heralded as the fastest object humans have ever made, has broken several records along the way. Now, it looks like NASA has used the probe to take the closest images of the Sun ever taken.

Each year since its launch, the Parker Solar Probe has been inching closer and closer to the star at the center of our solar system. While it has essentially touched the Sun at this point, the probe has now passed even closer, coming within just 3.8 million miles of the center of our solar system back in December. On this historically close flyby, the probe took more images of the Sun’s atmosphere.

At this point, the probe is basically traveling inside the Sun’s corona. It has touched the Sun and continues to fly without issue. It’s not only a testament to human invention and innovation, but it’s also to how far humans will go to learn more about the universe. There are, of course, myriad reasons why taking the closest images of the Sun possible is important. Most of all, though, they could help us better understand our Sun’s volatile activity.

One of the big hopes with Parker’s continued success is that we’ll be able to learn more about the solar atmosphere. This could help us eventually discover new ways to predict solar activity like coronal mass ejections (CMEs), solar flares, and more. Furthering this research could help us mitigate the effects of those dangerous solar eruptions, and perhaps even come up with better protections against the energy as a whole — something vitally important for any future spacecraft traveling outside the protection of Earth’s magnetic field.

These new images were taken by Parker’s Wide-Field Imager, which has proven to be a incredibly useful for capturing stills around our Sun. The imager views space in visible light, which means it sees things exactly the same way the human eye would. This removes any possibility for incorrect interpretation of the visuals seen in the images it takes.

But what makes the imager especially effective is that it isn’t pointed directly at the Sun. Instead, Parker’s Wide-Field Imager captures solar material as it comes off the Sun. This allows scientists to get an up-close-and-personal look at the origin of the solar wind that fills our solar system.

3.png-e1695200541979.png)