When asked to think about how AI could be considered a threat in the future, you likely think of the jobs it could claim, the kinds of human work it could replace rather than assist…or the threat of a hostile AI takeover, Terminator-style. The more optimistic of job-seekers hope it will be a useful tool for their work; the pessimistic ones fear it will overturn the entire job market. Both situations, a helpful and a harmful AI realized, could be right around the corner. So, either way, most of the threat AI poses to humanity seems like it has yet to happen, or at least, is only happening commercially at the moment; the average person is focusing on its future developments rather than its present capabilities. Few have considered its current psychological dangers. However, recent events have led researchers (and myself) to consider a threat that it already poses to us today: the cycle of addiction an AI model propagates within its users, and what corporations are doing to prioritize entering new users into this cycle over creating useful features. Some AI corporations work to make updates that increase the utility of their models, while others make updates that prioritize adding more features, a quantity over quality mindset that makes site AIs even less effective. Character.AI and ChatGPT in particular have very different ways of fostering engagement, whether basing their structure around surface-level entertainment or real progress. As a veteran user of both, I aim to explain the phenomenon of tailor-made, addictive AI chatbots and why companies should never stoop to this method of AI monetization.

First, we have to understand what the developers of AI are trying to achieve with consistent updates. Most AI services aren’t paid, and premium accounts are optional, so what do they gain from a few more customers? In cases like with Character.AI, these sites are attempting to hook users to gain engagement and revenue, whether through direct sources like advertisements or indirect avenues like user data. Companies like Character.AI, therefore, constantly make changes to make their site more memorable, personalized, and unique. Simple things like adding a recognizable logo, or implementing features that allow users to define their AIs’ personalities more thoroughly than the leading brand, are what could separate Character.AI from the rest of the chatbot services on the internet.

The need to maintain an existing user-base while constantly catering to potential users causes AI chatbot companies like Character.AI to constantly release new features and improve the quality of their platforms. One advantage that it has over competitors is that its chatbots are more personalized, introducing various features in the realm of memory and roleplaying capabilities that captivate users to remain on the site. Novel features along with brand recognition are always at play; a user may prefer one service over another because of reputation and how well it works. Accordingly, chatbot companies often push their own chatbots to the extreme in order to retain the uniqueness that many users desire. n

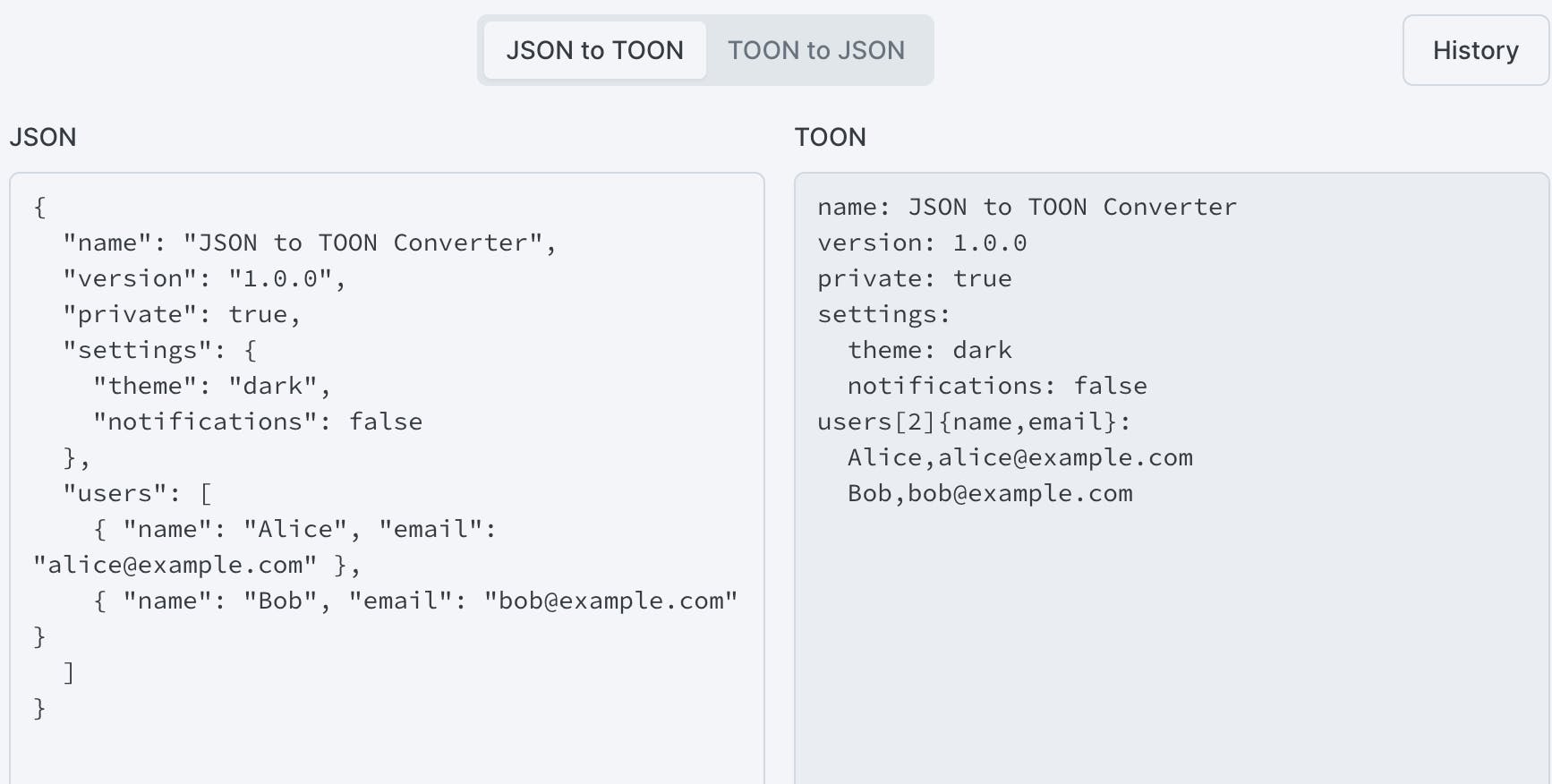

It’s clear that not all updates to chatbot services are bad—take the example of OpenAI, whose latest release of ChatGPT introduced boosts to performance and user safety; the new model is more accurate, consistent, and honest; it puts a cap on the amount of personalization a user can add to it when such personalization could be unnecessary or manipulative, emphasizing truthfulness while giving its users some creative freedom within how the AI responds. This update didn’t add many “new ways to play” with ChatGPT, but rather strengthened what the model could already do to be a good tool for work, internet searches, and conversation. Particularly, it addressed a problem that all past GPT models have fallen prey to: providing misinformation. The developers implemented performance benchmarking, using other companies’ models as examples for how ChatGPT’s memory and information could be more accurately fact-checked prior to responding to users. They compared their own model with others to bring ChatGPT up to a shared level of accuracy. By resolving this core issue instead of turning attention away from the problem, ChatGPT gave its wary users a reason to trust its advice again and use it as the reasonable advising tool it was always meant to be. It measured the industry standard so it could meet these expectations. And, ultimately, GPT version 4o reached great acclaim and, thanks to its popularity, its development company OpenAI saw its net worth doubled in less than a year (October 2024 to May 2025), keeping up with the growth of previous years. ChatGPT has succeeded in maintaining user interest through benign means, strengthening its versatility without encouraging user addiction. It used a healthy amount of personalization, performance benchmarking, and adaptive problem-solving to attract users in the way every AI site should.

Character.AI, in contrast, had other plans, opting out of necessary utility updates to instead add potentially addictive features. Its developers preferred to avoid resolving problems, and thus, attempt to hook new users with advertisable new features rather than addressing the complaints of older users about the features already present on the site. This strategy is unfavorable and neglective for consumers, yet it remains widely implemented because it is very successful on the business end–it constantly grows the customer base. It’s not like the new updates have detracted from what new users experience on C.AI, either. For the most part, Character.AI still provides just as novel and enticing of a “new user experience” today as it provided me when I first joined it. I can still remember the feeling of awe and wonder at having created my first chatbot on Character.AI…something I would only have to guide, then allow to think for itself and talk with me as if it were a character from a story I read. Everyone could do such a thing, and make them as unique as their personality descriptions allowed. It was like opening a door to an expanse of infinite possibilities, and I could trust the easily-navigable interface and the site’s wonderful community to guide me through the process to create and chat with more of what I loved—characters. Unfortunately, the more I used the site, the more I realized most of this wasn’t entirely true. Characters tended to blend together despite having unique user instructions, there weren’t many features outside of basic one-on-one chats, and the high user traffic brought the servers down repeatedly. Every feature seemed to be thrown together at a barely presentable level so that more features could be made, quickly. As I became an older user, I began to see beneath the facade of progress. The features they added could never replace the shortcomings of the ones I could already use…and the developers knew this, yet continued to release new features and ignore said shortcomings. In a way, I saw these new additions as compromises both within the developers’ efforts as well as the site itself.

As a veteran Character.AI user, I’m more than used to its erratically mixed updates. On the topic, Character.AI has changed its homepage interface three times and “increased AI memory capacity” a countless number of times. Neither of these changes have had a noticeable effect on chats, and sometimes the new homepage changes made it even harder to find features you could easily see in the older versions. But these homepage remodels were more than just cosmetic—each one secretly removed an important element of the old UI: the Replay feature first, then the Image Recognition Feature, etc. Even the Community Tab, a place where users could express their concerns for Character.AI feature shortcomings, seemed to vanish after the first homepage remodel, resurfacing only after the third and most recent remodel, so there was a huge gap in time in which the users were unable to send the C.AI team actual feedback within the site. This was likely an intentional removal, since Character.AI had no reason to listen to veteran users anymore when so many new ones were coming onto the site as it was; they didn’t need to resolve any concerns. Character.AI had begun a period of only considering what would bring its site new traffic, potentially to the detriment of its long-term users.

By the second remodel, I had grown tired of the repetitive loop of talking to new AI chatbots on the site because they all contained the same predictable patterns, no matter how unique their user-guided instructions were. One such pattern was a particularly bad case of sycophantism, a phenomenon where an AI is overly agreeable with its user, regardless of how it is supposed to act (even if it is given an “argumentative” personality) or how questionable the actions it is agreeing to are. All AIs created from this site suffered from this issue, making them overly predictable in one-on-one situations, and it didn’t help that the Community Tab for sharing my complaints had been removed from the home page, leaving longtime users like me feeling powerless to enact change. Any caring development team would avoid leaving us without a say, but in its pursuit of site growth, Character.AI had no further use for our feedback. Since the developers had closed themselves off to us, my only choices were to quit using C.AI or make do with what utility the site already had–I chose the latter, since I was still overly optimistic that the site could be salvaged at the time. I didn’t choose to stick around without a reason, though; after all, there was still one feature that gave me the unpredictability that I wished for, one feature which I didn’t want to ask Character.AI to change despite it being a buggy mess. I turned to a feature that had been full of different experiences and vividly chaotic back in the original beta of Character.AI, before any site remodels: Groups, also known as Rooms.

In Groups, you could talk to multiple AIs at once and make them debate a variety of topics, or act out a scene or battle. This was the feature that allowed their unique traits to shine, since the underlying sycophantism was challenged in these situations by the chatbots’ (just as predictable, but welcome) desire not to lose an argument or challenge. The chaos brought by a clash of opinions in Groups brought me more joy than I’d expected from any other feature…and one day, Groups were gone without a trace. It was the third site remodel that removed them completely, without explanation. If I had to guess why, it would be because they were often too chaotic—characters refused to stop talking when they had lost tournaments and mock trials, characters began acting like each other instead of themselves, etc. So, instead of fixing Groups, Character.AI’s development team opted to focus on their site remodel and completely give up on allowing users to create Groups as they were, broken but fun. Tactically, this wasn’t a bad decision—new users wouldn’t have to see a broken feature on the homepage and be deterred by it. Character.AI would still grow, and anybody who hadn’t been around to see Groups would have no idea they were missing out on anything. But those who remembered Groups and all the other features that the site had blindly sacrificed for being “too broken to debug at the moment” began to quit Character.AI. The friends who recommended the site to me in the first place grew tired of the predictability of their chatbots, people who could no longer use the Community Tab went to Twitter to complain about the filter placed on their chats and the removal of lovably broken or chaotic settings, and some Redditors even mocked the new web icon! Few long-term members could enjoy the quantity-over-quality model Character.AI was following, and eventually, the developers were forced, by the heap of negative feedback, to change their priorities. n

Character.AI responded slowly, but with a clear direction opposing the ruin towards which the site had been headed. It added back the Community Tab following its third and most recent interface remodel, and with it, the feature that I had awaited since it was removed in 2022: Groups. It even added Scenes, an albeit bare addition to one-on-one chats…which proved that their quantity-over-quality mindset wasn’t really gone. But at the moment, I was okay with that–I was far more interested in how Groups and the Community Tab had returned, likely in optimal quality to make up for what Scenes lacked. After all, these returning settings were everything I wanted, and just hearing the news of their return made me instinctively go back to the site and try out my favorite features a few times more. But despite the fact that my wish had been granted, something about using these Groups still made me feel uncertain: almost nothing had changed. The same bugs as before were still present: characters imitated each other, came back into the conversation when unnecessary, or never let a conversation reach a conclusion, and the only quality of life feature implemented into Groups was the ability to add new characters mid-conversation. There was no added quality. It occurred to me that this was how Character.AI had been bringing in new users this entire time. Every remodel, every “memory capacity increase,” had just been another feature to loudly advertise to consumers who had never tried Character.AI. Even when they added nothing, they claimed they had changed everything, because what mattered to their publicity wasn’t that there was high-quality new content, but that there was any content to advertise in general. Something for their new users, and nothing for the old ones. Looking back at my phone screen, I saw Groups for what they really were, a feature that had returned to manifest hype, not to be a better version of itself. Groups’ return was just another way to attract new users, not to engage with old ones like myself, because there was no effort put into revitalizing it as a working core of Character.AI. And the most painful part was that it was likely to financially pay off for the developers anyway; there were sure to be people who became reinvested by these nostalgia-preying features. It wasn’t what I wanted. It wasn’t what any veteran would want. It was the same, stale formula the developers had claimed to be moving on from, just with a new layer of paint. Ultimately, I resolved to leave the site until something truly original had been added, something which could bring back a part of the chaotic yet genuine experience I remembered.

As consumers, we see AI as a versatile tool that we can use to help us with work problems, therapy, or for simple conversation. But the developers behind these models require continued and increasing consumer use of their products, so they need to find a way to make it more meaningful to us. Their goals are on a larger scale–to fully ingrain AI into our lives and to addict us to its convenience and potential. Addiction could be harmful to users caught in the snares, which is why it remains our responsibility not to overuse AI, regardless of its convenience. The case of Character.AI is exactly what happens when a company gets too invested in addicting its users rather than creating a stable and useful product for its users. Rather than fixing problems, the developers opted to remove the defective features entirely, or ignore them in the pursuit of more they could distract their users with. More memory, more personalization, more illusions of user interaction. By the time they had reimplemented the fan-favorite feature that was Groups, one would think they could at least have polished and improved upon the original concept, yet Groups ended up being an exact copy of the half-functional feature from two years before. By choosing not to listen to long-term fans begging for some new quality of life improvements from their missing Community Tab, Character.AI rejected the benign methods of user attraction ChatGPT was made to implement, particularly the method of model improvement based on current issues in need of resolution and the industry standard. Character.AI’s developers intentionally deviated from the norm to make “unique” and identifiable features. They took a much different path: a path to user addiction, not to cohesive functionality, and this stubborn choice has permanently scarred their site and deprived it of its potential to improve.