The promise of digital freedom has always been central to the internet’s identity. Yet today’s internet is dominated by a handful of tech giants, often feels more like a series of digital cages than the open frontier it was meant to be. These centralized platforms control what we see, who we can reach, and how we express ourselves online.

In this article, we’ll examine how the centralized internet has created comfortable chains of dependency that users willingly accept. We’ll look at Web3 technologies that promise to break these chains through decentralized infrastructure and user-owned identity. Finally, we consider whether true digital freedom is possible or if some form of governance will always emerge.

History of Digital Control: From Open to Closed

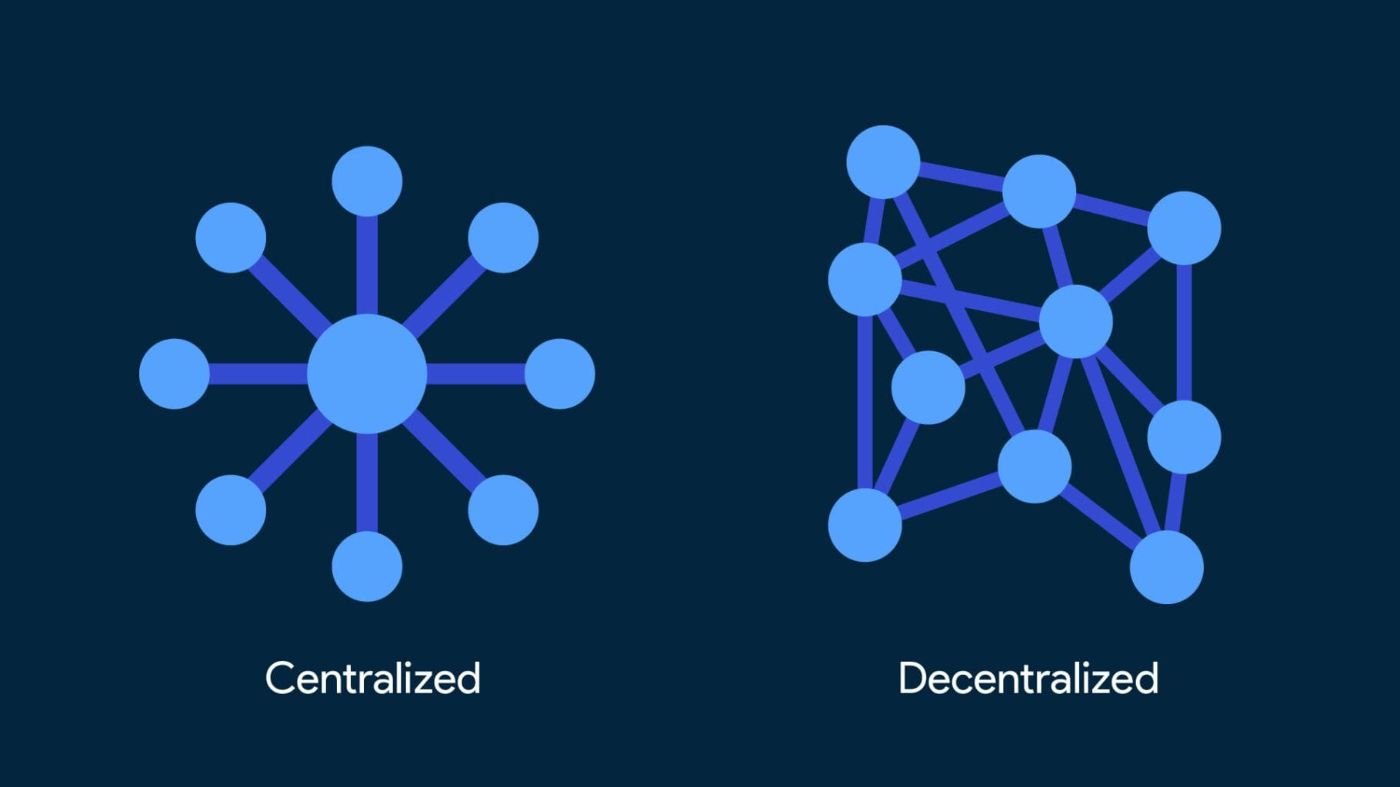

Although the internet began as a decentralized network designed to resist control, its evolution tells a different story. The transformation from an open communication system to today’s centralized platforms reveals how convenience and efficiency gradually replaced freedom and autonomy. Generally, most experts would agree that we can trace this evolution through three distinct eras: the early decentralized web, the rise of platform capitalism, and the emerging Web3 response.

The Early Internet: Distributed by Design

When the internet first became widely accessible in the 1990s, it embodied genuine decentralization. Users ran their own websites, email servers, and discussion forums. No single company controlled access to information or determined whose voice could be heard.

Another important characteristic of this early internet was its resistance to censorship. Information lived on thousands of independent servers worldwide. Shutting down one website or server had minimal impact on the overall network. Users communicated directly through protocols like email and IRC without corporate intermediaries monitoring or filtering their conversations.

This was essentially the “wild frontier” of digital communication. There were few rules imposed by platforms because platforms as we know them today didn’t exist. Although the technology was more complex to use, it offered genuine digital autonomy. Users controlled their own data, chose their own software, and participated in truly open networks.

Web 2.0: The Platform Trap

The shift toward centralized platforms began in the early 2000s with the rise of social media and cloud services. These platforms offered unprecedented convenience, professional-looking websites without technical knowledge, instant global communication, and free access to powerful tools.

However, this convenience came with hidden costs. Users gradually surrendered control over their data, communications, and digital identities in exchange for ease of use. The platforms produced no content themselves but captured enormous value by controlling access to user-generated information.

The biggest concern is that this centralization created single points of failure and control. A few corporations now determine what billions of people can see, say, and do online. Platform policies can silence voices, algorithms can bury information, and service disruptions can break entire sectors of the digital economy. As one researcher notes, this has created “single points of failure” that threaten both individual freedom and societal stability.

Moreover, the economic model underlying these platforms depends on surveillance and manipulation. Companies collect vast amounts of personal data to target advertising and influence behavior. Users become products to be optimized rather than customers to be served. The promise of “free” services masks the true cost: surrendering digital autonomy and privacy.

The Web3 Response: Reclaiming Digital Sovereignty

Web3 represents a direct response to the limitations and risks of centralized platforms. This new generation of internet technologies aims to return control to users through cryptographic protocols, decentralized storage, and blockchain-based identity systems.

The core innovation lies in eliminating trusted intermediaries. Instead of relying on companies to store data, facilitate transactions, or verify identities, Web3 systems use cryptographic proofs and distributed networks. Users can interact directly with each other through protocols that no single entity controls.

However, Web3 technologies face significant adoption challenges. The user experience remains complex compared to centralized alternatives. Transaction costs can be high, and the technology requires users to understand concepts like private keys and smart contracts. These barriers limit Web3 to early adopters and technically sophisticated users.

Centralized Internet: The Soft Cage

Modern internet platforms have perfected the art of creating dependency while maintaining the illusion of choice. They offer undeniable benefits like instant communication, vast libraries of content, powerful tools for creativity and productivity that make them difficult to abandon even when users recognize their limitations.

The Convenience Trap

Centralized platforms succeed by reducing complexity and friction. Creating a social media account takes minutes. Storing files in the cloud requires no technical knowledge. Video calls work seamlessly across different devices and networks. This convenience creates powerful network effects that entrench platform dominance.

Users gradually integrate these services into their daily routines, professional workflows, and social relationships. The switching costs both technical and social become prohibitive. Moving to alternative platforms means losing access to friends, abandoning years of content, and learning new systems. The platforms become essential infrastructure rather than optional services.

The psychological dimension of platform dependence runs even deeper. Algorithms are designed to capture attention and drive engagement through carefully calibrated rewards and notifications. Users develop habitual behaviors around checking for updates, seeking validation through likes and comments, and consuming algorithmically selected content. Breaking these patterns requires conscious effort that many users find difficult to maintain.

Data as Chains

Perhaps the most insidious aspect of platform dependence involves data ownership. Users create enormous amounts of valuable information: photos, messages, creative work, social connections, behavioral patterns that platforms claim ownership over through terms of service agreements.

This data becomes a form of digital hostage. Users cannot easily export their complete social graphs, message histories, or content libraries to competing platforms. The platforms use this data lock-in to maintain their market position and extract economic value from user activities. The more data users contribute, the stronger their chains become.

Additionally, platforms use this data to build detailed profiles for advertising and manipulation purposes. Users have little visibility into how their information is processed or shared. They cannot correct errors, delete unwanted inferences, or prevent their data from being used in ways they find objectionable. The platforms know their users better than users know themselves, creating fundamental power imbalances.

The Web3 Proposition

Web3 technologies offer several mechanisms for breaking free from centralized control. By distributing power across networks of users rather than concentrating it in corporate entities, these systems promise to restore digital autonomy and resist censorship.

Immutable Ledgers and Censorship Resistance

Blockchain technology provides the foundation for censorship-resistant communication and content storage. Once information is recorded on a distributed ledger, removing it requires coordinated control over the majority of network participants. This makes takedown requests and content suppression much more difficult to implement.

Web3 hosting systems distribute website data across networks of nodes rather than centralized servers. Each node stores encrypted fragments of the total information. Users access content by querying multiple nodes simultaneously. This architecture eliminates single points of failure that governments or corporations can pressure to remove content.

Decentralized storage systems like IPFS (InterPlanetary File System) use content addressing to ensure that identical files remain accessible even if some hosting nodes go offline. The content itself determines its network address rather than depending on specific server locations. This makes content both censorship-resistant and highly available.

User-Owned Identity

Traditional internet identity depends on accounts created and controlled by platform companies. Users cannot transfer their identities between platforms or maintain consistent personas across different services. Web3 systems introduce self-sovereign identity that belongs to users rather than platforms.

Decentralized identifiers (DIDs) enable users to create and manage their own identities using cryptographic keys. These identities work across multiple platforms and applications without requiring permission from any central authority. Users can prove their identity, establish reputation, and maintain relationships independently of platform policies.

Web3 domains represent another form of user-owned identity. Unlike traditional domain names controlled by registrars and subject to government seizure, Web3 domains are owned through blockchain smart contracts. Users can create censorship-resistant websites, simplify cryptocurrency transactions, and establish consistent online identities across the decentralized web.

Verifiable credentials allow users to prove specific attributes about themselves without revealing unnecessary personal information. For example, users could prove they are over 18 years old without disclosing their exact birthdate or identity. This enables privacy-preserving interactions while maintaining the verification capabilities that many applications require.

Control in New Forms

Despite the promise of decentralization, Web3 systems face several challenges that could reproduce centralized control in different forms. The technology may distribute power more broadly than current platforms, but it cannot eliminate power imbalances entirely.

Validator Oligopolies and Infrastructure Monopolies

Most blockchain networks rely on validators or miners to process transactions and maintain consensus. Although these roles are theoretically open to anyone, practical requirements for technical expertise, hardware resources, and economic stakes create barriers to participation. Large operators often dominate network governance through their control over validation infrastructure.

The geographic distribution of validators creates additional vulnerabilities. If most validators operate in specific jurisdictions, governments could potentially influence network behavior through regulatory pressure. The Tornado Cash sanctions demonstrated how traditional legal systems can impact decentralized technologies by targeting the infrastructure and service providers they depend on.

Cloud computing providers represent another potential chokepoint for Web3 applications. Many decentralized applications actually run on Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, or Google Cloud platforms. These centralized providers could terminate services or implement filtering at the infrastructure level, undermining the censorship resistance that Web3 systems promise to provide.

Protocol Governance and Developer Control

Decentralized protocols require ongoing development and maintenance to remain functional and secure. The small communities of core developers who control protocol upgrades wield enormous influence over network behavior and user capabilities. Changes to consensus mechanisms, fee structures, or governance procedures can fundamentally alter how networks operate.

Fork decisions; where networks split into competing versions, reveal the political dimensions of supposedly neutral technical systems. These splits often reflect disagreements about censorship policies, scalability trade-offs, or economic models. Users must choose between different visions of how their networks should function, potentially fracturing communities and dividing resources.

The complexity of protocol governance often excludes ordinary users from meaningful participation. Technical proposals require specialized knowledge to evaluate. Governance tokens may concentrate voting power among wealthy holders or early adopters. The promise of democratic control over digital infrastructure may prove illusory if most users cannot effectively participate in governance decisions.

Economic Gatekeeping

Web3 systems frequently use token-based mechanisms to allocate resources and govern behavior. These economic approaches can create new forms of exclusion based on wealth rather than institutional position. Users with more tokens can influence network policies, access premium features, or extract economic rents from network activities.

The high transaction costs on some blockchain networks effectively exclude users who cannot afford to pay fees for basic operations. This creates tiered access where wealthy users enjoy full functionality while others face significant limitations. The promise of financial inclusion may be undermined by the economic barriers that Web3 systems themselves create.

Additionally, the volatility and speculation surrounding cryptocurrency markets can make Web3 systems unstable platforms for essential communication and commerce activities. Users may face unpredictable costs and service quality as token prices fluctuate and network congestion varies with market conditions.

Between Freedom and Responsibility

The debate over Web3’s potential for digital freedom raises fundamental questions about the relationship between technological architecture and social governance. Should online spaces have minimal rules to maximize individual liberty, or do some forms of collective control remain necessary to prevent abuse and protect vulnerable users?

The Moderation Dilemma

Traditional platforms employ content moderation policies to address harassment, misinformation, fraud, and other forms of harmful behavior. These policies are imperfect and often controversial, but they serve legitimate purposes in maintaining civil discourse and user safety. Web3 systems must somehow address these same challenges without centralized enforcement mechanisms.

Community-based moderation represents one approach to this problem. Users can create shared blocklists, reputation systems, and social norms that discourage unwanted behavior. However, these informal mechanisms may prove inconsistent, biased, or vulnerable to manipulation by coordinated groups.

The immutable nature of blockchain records complicates efforts to remove genuinely harmful content like harassment, doxxing, or illegal material. What seems like a feature for censorship resistance becomes a bug when users need protection from persistent abuse or want to remove regrettable posts from their permanent record.

Ethical Boundaries in Decentralized Systems

Even the most libertarian web users generally acknowledge some need for boundaries around clearly harmful activities like child exploitation, terrorist recruitment, or financial fraud. The challenge lies in implementing these boundaries without creating systems that can be abused for broader censorship purposes.

Technical solutions like zero-knowledge proofs might enable selective disclosure of information for law enforcement or safety purposes without compromising general privacy. However, implementing these systems requires cooperation between developers, users, and traditional institutions that may have conflicting interests and priorities.

The global nature of Web3 networks also creates jurisdictional challenges. Different countries have varying laws and cultural norms around acceptable speech and behavior. A truly decentralized system cannot easily accommodate these differences without fragmenting into separate networks or creating complex regulatory compliance mechanisms.

Shaping the Next Chapter

The future of digital freedom will likely depend more on social and political choices than on technological capabilities alone. Web3 tools provide new options for organizing online communities and resisting centralized control, but they cannot automatically create the democratic and equitable digital society that many users desire.

Community-Driven Evolution

Successful Web3 platforms will need to develop governance mechanisms that can adapt to changing user needs and social conditions. This requires more than just technical decentralization — it demands new institutions and practices for collective decision-making that can operate across diverse and distributed communities.

Users and developers must actively resist the tendency toward re-centralization that emerges naturally in complex systems. This means making conscious choices to support smaller validators, use diverse service providers, and participate meaningfully in governance processes even when it requires additional effort or cost.

The challenge lies in creating systems that combine the efficiency and usability of centralized platforms with the autonomy and resilience of decentralized networks. This may require hybrid approaches that use centralized services for convenience while maintaining decentralized alternatives for critical functions.

Maintaining Digital Sovereignty

True digital freedom requires users to take responsibility for their own security, privacy, and data management rather than outsourcing these concerns to platform companies. This involves learning new skills, accepting additional complexity, and making trade-offs between convenience and control.

Educational initiatives can help users understand the implications of their technology choices and develop the capabilities needed to participate effectively in decentralized systems. However, widespread adoption will ultimately depend on improving the user experience to make Web3 tools accessible to non-technical audiences.

The goal should not be perfect decentralization which may be neither possible nor desirable, but rather systems that distribute power more broadly and give users meaningful choices about how they interact with digital technologies. Freedom online, like freedom offline, requires constant vigilance and active participation to maintain.

Conclusion

The question of whether Web3 can break the chains of online censorship has no simple answer. While these technologies offer new tools for resisting centralized control, they introduce their own challenges and limitations that could undermine their liberating potential.

The centralized internet succeeded by offering genuine value to users, convenience, connection, and capabilities that were previously impossible. Web3 alternatives must match or exceed this value proposition while providing the additional benefits of user ownership and censorship resistance. This remains a significant technical and user experience challenge.

Moreover, the social and political dimensions of digital freedom cannot be solved through technology alone. Building truly free and democratic online spaces requires ongoing attention to governance structures, community norms, and power dynamics that extend far beyond protocol design and smart contract code.

The internet we create will reflect the choices we make today about how to balance individual liberty with collective responsibility, efficiency with resilience, and innovation with stability. Web3 technologies expand our options for making these choices, but they do not make the choices for us.

Users who value digital freedom must be prepared to sacrifice some convenience and accept additional responsibility for their online lives. The alternative, continued dependence on centralized platforms, may preserve comfort in the short term but ultimately threatens the open and democratic internet that so many users claim to desire.