More than a kilometer underground, in an old gold mine in a small Australian town, a group of scientists is building a laboratory that aims to look where no one has been able to look before. Its name is SABER South, and its mission sounds simple but borders on the impossible: detect the particles that make up dark matter, that mysterious component whose existence, until now, we only intuited.

The search begins. To understand how we got here, we have to travel back to 1998. That year, an experiment in the Gran Sasso underground laboratory in Italy recorded a strange signal that some interpreted as a clue to dark matter. That observation, known as DAMA/NaI, ignited a scientific career that has not stopped since.

Now, Australia enters that global race. According to ABC News Australia, SABER South will be the southern hemisphere’s first dark matter detector and will begin collecting data next year. Its director, physicist Phillip Urquijo, explains that the objective is to reproduce the Italian observations and check whether these signals are real or the product of interference from the environment.

Currently, three other teams – in Italy, Spain and South Korea – are still trying to replicate the original experiment. However, the Australian project has a unique advantage: its location in the southern hemisphere will allow the data to be compared with those from the north and rule out seasonal or local effects.

The enigma of the invisible universe. Promoted by the University of Melbourne and the ARC Center of Excellence for Dark Matter Particle Physics, it seeks to understand the nature of a substance that surrounds everything, but that no one has ever seen.

The Standard Model of physics accurately describes the particles and forces we know, but it still leaves too many gaps unfilled. One of the biggest is this: why don’t galaxies disintegrate? What holds them together if everything we see—planets, stars, gas, dust—barely adds up to 5% of the universe? The rest is hidden from view. Physicists calculate that around 27% would be dark matter and another 68% would be dark energy. Physicist Elisabetta Barberio, director of the ARC Center of Excellence for Dark Matter Particle Physics, puts it bluntly: “Between 75% and 80% of the universe is made of something we can’t see or touch. This experiment brings us closer to discovering what most of the cosmos is really made of.”

Therefore, if SABER South manages to detect WIMPs—those hypothetical massive particles that interact weakly—we would be facing a new form of matter and, perhaps, facing physics that goes beyond the Standard Model. Simply put: it would demonstrate that almost everything that exists has a tangible structure. And every time humanity has understood a new force or particle, technologies that previously seemed like science fiction have appeared: semiconductors, lasers or magnetic resonance.

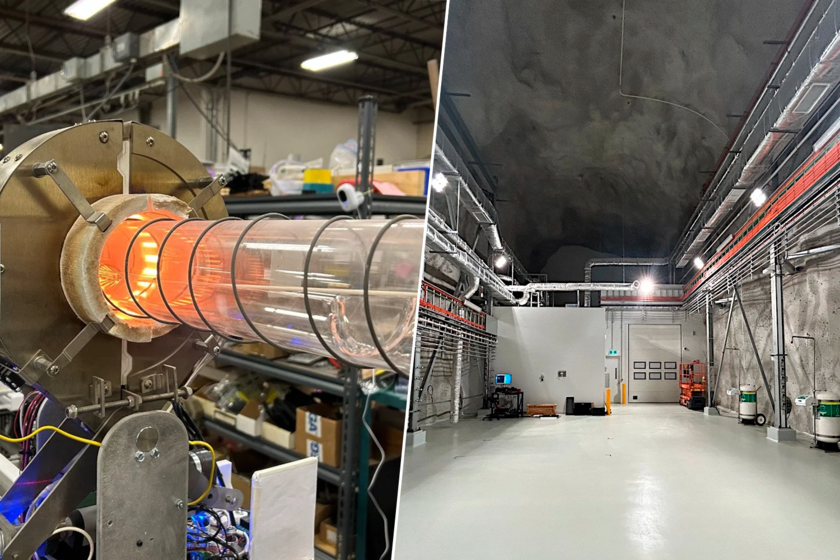

A mine converted into a cosmic laboratory. The experiment is carried out at the Stawell Underground Physics Laboratory (SUPL), excavated at a depth of 1,025 meters, a distance that is equivalent to a protection of almost three kilometers of water, enough to block cosmic rays and natural radiation that could interfere with the measurements.

The laboratory is air-conditioned, has filtered air and has data connections linking to the University of Melbourne. At its heart, a room-sized detector houses ultrapure sodium iodide (NaI) crystals. When a WIMP particle collides with an atom in the crystal, it produces a tiny flash of light, so weak that it lasts just a few nanoseconds. These flashes are captured by photomultiplier tubes (PMT), devices capable of transforming light into measurable electrical pulses.

The crystals are immersed in a scintillating liquid—linear alkylbenzene (LAB)—which acts as a “veto”: if the LAB detects light at the same time as the crystal, the event is discarded as background noise. The entire system is sealed inside a low-radioactivity stainless steel tank, surrounded by alternating layers of steel and polyethylene, and monitored from above by a muon detector.

A machine that listens to itself. SABER South will operate almost autonomously. According to the technical reports of the project, the system records in real time the temperature, humidity, voltage of the detectors, the flow of nitrogen gas and even the vibrations of the mine. If something goes out of normal values, it generates an automatic alert. In addition, human presence will be minimal: scientists will monitor the data remotely and will only access the laboratory for specific maintenance tasks.

Even before its construction, the operation of the detector was simulated with the GEANT4 software, a tool also used by NASA and CERN. These simulations allowed us to estimate the background radiation levels and optimize the sensitivity of the system. Each light pulse captured will be analyzed with programs designed to distinguish between noise and possible real signals.

Some are not optimistic. In a study by the University of Ottawa, physicist Rajendra P. Gupta suggests that what we think we see as dark matter could be just a mathematical effect. Their model suggests that the fundamental constants of the universe could vary with time, and that the so-called “tired light”—the loss of energy of photons as they travel through space—would explain the observations that until now we attribute to an invisible mass.

Waiting for the flash. For years to come, SABER South’s crystals will remain in the shadows of the mine, waiting for a flash so faint it could barely illuminate a speck of dust. If that signal is confirmed, it would be the first direct trace of dark matter, the invisible glue that holds galaxies together. But if it doesn’t appear, it will also be an answer: a sign that perhaps the universe works in a way we don’t yet understand.

As theoretical physicist Nicole Bell, from the University of Melbourne, detailed: “This project represents the definitive quest to understand the world in which we live.” And perhaps, in that tiny spark beneath the ground, humanity will find the answer to a question it has been pursuing for decades: what is the universe actually made of?

Imagen | SABRE South

WorldOfSoftware | The strangest event that humanity has witnessed occurred in 2019 under a mountain in Italy