For years, many of us have thought of insects as something foreign to our table, but they have been part of space history for much longer than we imagine. Even before the first astronauts reached orbit, these small species had already demonstrated that they could withstand the conditions of flight. Today, with long-duration missions on the horizon, the conversation has changed. Europe wonders if these animals, so nutritious and easy to maintain, could become a real option to feed those who live far from Earth.

Why insects. Although they are still a culinary rarity in Spain, insects are part of the regular diet of billions of people. The FAO estimates more than 2,000 species consumed on different continents, valued for their contribution of protein, iron, zinc and beneficial fats. Their ability to develop with few resources and transform waste into useful biomass makes them an attractive candidate for controlled food systems. That is why several European teams are analyzing its nutritional potential and its viability in environments where every gram counts.

What we know about microgravity. Insect research in space has accumulated decades of data, from early suborbital flights to tests at orbital stations. During this journey, different species have been tested, with very different results: some managed to complete essential phases of the life cycle in microgravity and others showed sensitivity to factors such as movement or radiation. This contrast has been useful to understand what biological mechanisms remain stable outside of Earth and what processes are altered even in very resistant organisms.

What the ESA is looking for. The European team is working with a specific idea: to know in detail how these organisms behave in key phases of their development when they spend prolonged time in orbit. The agency has brought together diverse profiles to study their ability to recycle nutrients and produce protein under controlled conditions, a line that already has candidate species such as the common cricket and the mealworm. This research aims to clarify what biological requirements should be met before considering its production in long-duration missions.

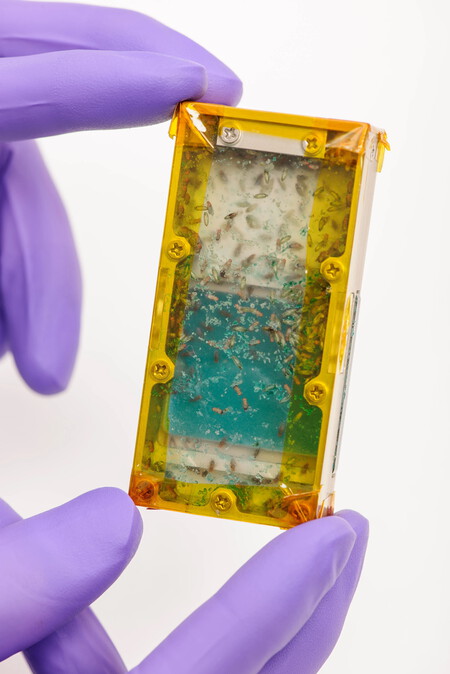

Fruit fly habitat used for scientific research in space

Although there is an extensive history of testing with insects, much of the results are scattered and come from short missions. The majority of experiments did not reach times that would allow the complete life cycle of a species to be followed, an essential requirement to evaluate its use in long missions. Furthermore, many of these investigations are old and used different methodologies, making it difficult to compare them. That is why ESA is preparing new studies specifically aimed at measuring changes in reproduction, development and behavior in orbit.

Drosophila model. NASA’s experience with Drosophila melanogaster has demonstrated its usefulness as a model organism for understanding physiological changes in space. The agency highlights that it shares a good part of the genes related to human diseases and that its accelerated reproduction facilitates the analysis of several generations. The Fruit Fly Lab, installed on the International Space Station, makes it possible to follow their behavior and freeze samples for study on the ground. It also incorporates a centrifuge that helps distinguish which effects depend on gravity and which are linked to space radiation.

Astronaut James D. “Ox” Van Hoften examines a bee experiment

From the laboratory to the menu. For now, the food use of insects in space missions continues to be a line of study and not an immediate application. Researchers need to check how they behave in prolonged phases and what it would mean to stably grow them in inhabited modules. Added to this is the challenge of transforming this biomass into safe, manageable and acceptable products from a nutritional and sensory point of view. Everything is moving in the direction of exploring options, not automatically incorporating them into the astronauts’ menu.

Images | ESA | POT

In WorldOfSoftware | Astronauts’ food is not appetizing at first, especially in China