In the summer of 2016, streaming TV was still figuring itself out. Netflix had been producing original series for a few years, with occasional company from Amazon, Hulu, Yahoo and the like. Disney+, Apple TV and HBO Max were still gleams in some billionaires’ eyes.

Would the future of streaming be in wild, form-breaking experimentation, like Netflix’s “Sense8”? Would it be nonlinear storytelling, like its revival of “Arrested Development”? Would it be in prestige comedies, like “BoJack Horseman,” or prestige-flavored dramas, like “House of Cards”?

I’m not sure anybody was expecting the answer to come from a popcorn horror thriller that premiered that July. But the success of “Stranger Things,” which is about to end its run after nearly a decade, told us that the future of streaming TV was largely in the past. (The first four episodes of the final season arrive on Wednesday night.)

I don’t mean merely that the series is a period piece, though its evocation of the 1980s in small-town Hawkins, Ind., is a big part of the appeal; you can almost smell the hair spray and taste the Orange Julius. I mean that the series is an entertainment machine built by repurposing vintage pop-culture parts — something that streaming would come to specialize in.

There is the Spielbergian coming-of-age through-line, familiar from movies like “E.T.” (in which Dungeons & Dragons also played a character-establishing role); the horror and adolescent bonding of Stephen King; the chills (and typography) of ’80s supernatural tales; the mean jocks and soulful goths of John Hughes; the well-curated pop-culture quotations, from Kate Bush to “The NeverEnding Story” to the casting of Winona Ryder of “Heathers” and “Beetlejuice.” It’s a big Halloween bowl of retro candy that invites you to remember when, one sugary bite at a time.

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade 1989

Season 3, Ep. 6 2019

Jurassic Park 1993

Season 3, Ep. 7 2019

Firestarter 1984

Season 1, Ep. 4 2016

The Fog 1980

Season 3, Ep. 2 2019

The Goonies 1985

Season 2, Ep. 5 2017

This is not to say that “Stranger Things” is merely derivative. Pastiche can be its own kind of art, and what Matt and Ross Duffer created was fun and fresh, especially in its early seasons.

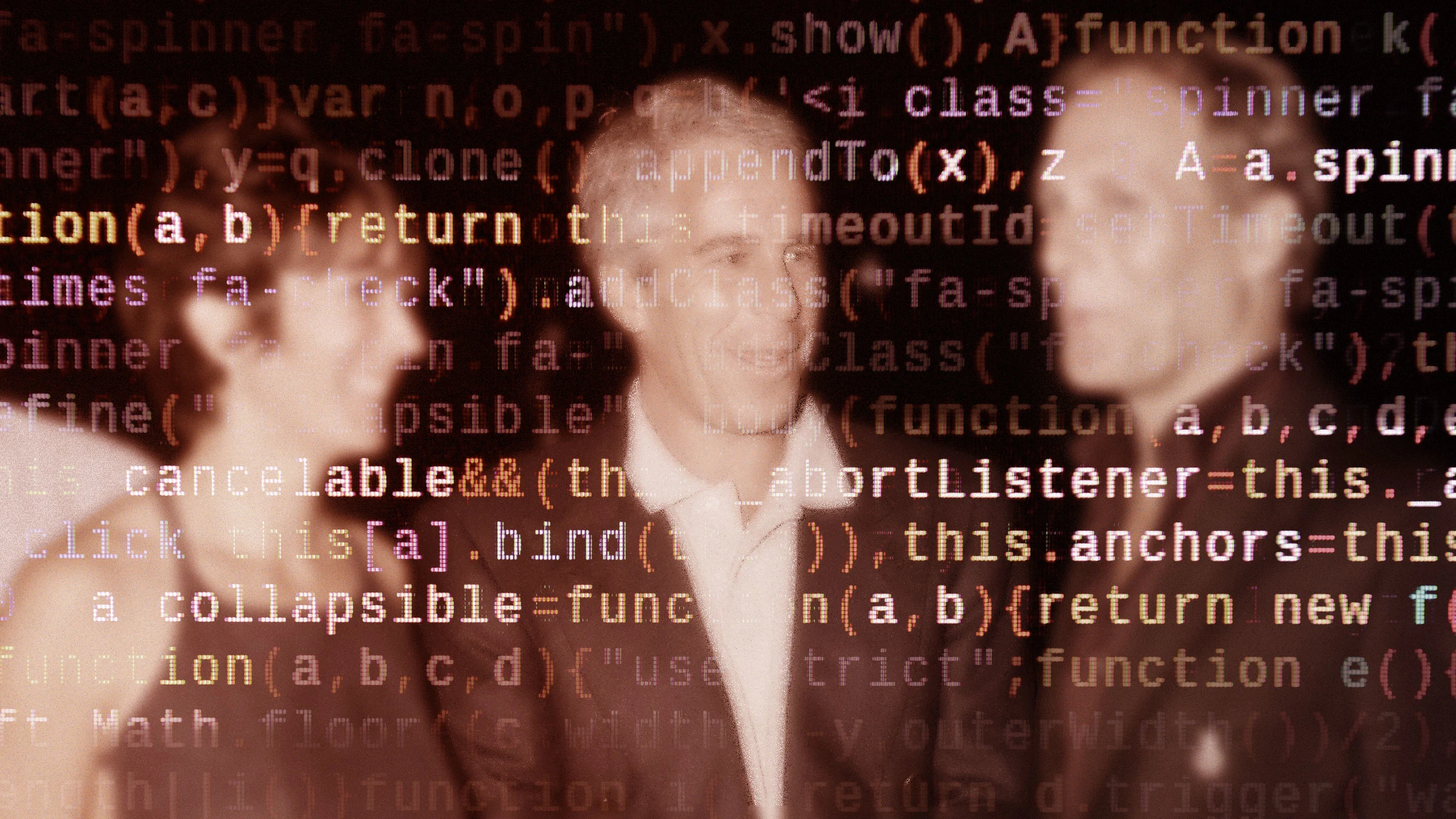

But this is to say that “Stranger Things” succeeds in part because of how well it evokes pop culture that audiences already love. It is, in other words, a human-made equivalent of the algorithm, the software engine that has come to define the experience and the aesthetic of streaming.

Late in 2015, I tried to define in this newspaper what streaming was and how it differed from TV as we’d known it. “Streaming,” I wrote, “has the potential, even the likelihood, to create an entirely new genre of narrative.” As has always been true in TV, the way you watched shows on streaming would in part determine the kind of shows you would watch on streaming — their shape, their pace, their style.

I certainly didn’t predict “Stranger Things.” Even now, it’s a show that I find it hard, as a critic, to entirely get a grip on. It’s not exactly TV and it’s not exactly film; it’s entertaining but baggy; it never met a subplot it could do without.

But in retrospect it is the show of the past decade that best fits the mechanisms that make streaming streaming.

What are those? The medium encourages binge-watching and immersion. The viewing experience isn’t bound to a calendar schedule (thus new “Stranger Things” seasons come around like a comet with an irregular orbit). It assumes an audience with time to burn (see the last season finale, which ran a butt-numbing two hours and 22 minutes). Above all, its viewers found new shows through recommendations of the mighty algorithm.

“If you liked that, you’ll like this next” is the guiding philosophy of streaming. And “Stranger Things” — a pop-culture phenomenon made from the spare parts of a generation’s worth of pop-culture phenomena — was that philosophy embodied.

It’s not that Netflix invented the idea of copying TV success (we all know that imitation is the sincerest form of television), but the algorithm supercharged it, automated it and made it part of the creative operating system.

It’s why you see a menu of similar thumbnail recommendations once you finish streaming a favorite series, encouraging you not to discover but to replicate. But the spirit behind it also explains why so much original streaming TV feels like the creative product of an algorithm. Consider the recent Netflix drama “The Beast in Me,” which pairs familiar prestige-TV stars (Claire Danes of “Homeland” and Matthew Rhys of “The Americans”) in a grim, upscale thriller that vaguely recalls something you might have seen on early 2010s Showtime or FX.

Creating the new by swallowing and regurgitating the old is also the signature move of generative A.I., which may be why that medium is so effective at creating works of burnished nostalgia. On Instagram and TikTok, accounts with names like “Maximal Nostalgia” serve up honeyed, uncanny images and videos that testify to how much better life was in a 1980s and 1990s that never existed.

In a video scored to Alphaville’s “Forever Young,” teens with poufs of feathered hair hang on the street and tell us, “Face-to-face connection is just so much better.” In another, a girl brandishes video-arcade tokens in a hand that has at least six digits. A post imagines small-town life in 1986 Indiana, where kids walk on a train track, an image that was itself a signifier of nostalgia in the 1986 movie “Stand By Me.” One of the top comments says, “Yesss! I love the ‘Stranger Things’ vibe.”

Stand by Me 1986

Season 1, Ep. 5 2016

Aliens 1986

Season 2, Ep. 1 2017

The Terminator 1984

Season 3, Ep. 7 2019

St. Elmo’s Fire 1985

Season 2, Ep. 1 2017

The Exorcist 1973

Season 2, Ep. 9 2017

These videos tell you how much purer and more authentic the old times were, even if they are the opposite of authentic. They are, like “Stranger Things,” constructed from ideas of the past borrowed from shows and movies and advertisements. They make wistful fogies of us all, even, or especially, those who were too young to experience the real-life version.

“Stranger Things” is a cut above A.I. slop. At its best it is funny and charming. The kids have a reasonable amount of fingers. But it starts from a similar nostalgic impulse. Whatever affection it earns for itself, it starts by borrowing the affection you had for its influences. And however spooky its supernatural horrors, it trades on warm feelings for bygone, analog times. (Indeed, the premise of the Upside Down — military experiments open up a dreadful parallel dimension that layers onto our physical world — is not a terrible metaphor for the arrival of the internet.)

Soon, “Stranger Things” will itself be pop history, added to the cultural library to be remixed and mined for references. I don’t know if streaming TV will create anything else like it, but I can bet that it will try to. There must always be something, similar to something you liked before, for you to Play Next.