On October 10-11, 2025, the Cyber Statecraft Initiative and Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and Digital and Cyber Group held the tenth annual Cyber 9/12 competition virtually in New York City. The competition welcomed over twenty teams from ten different states across the United States. Stepping into their new roles as government policy advisors, students were tasked with providing insights and recommendations for the Principals Committee of the US National Security Council on how to respond to a complex cyber crisis threatening US national security and global stability.

Each team was presented with a fictional scenario focused on a cyber operation in which a Chinese state-sponsored cyber group, Volt Typhoon, had breached multiple US electric utilities, impacting critical military infrastructure, including US Air Force bases in Illinois, Missouri, California, Hawaii, and Guam. What started as a localized infiltration quickly escalated due to the interconnected nature of the power grid, and the fictional breach plunged large portions of the central United States into darkness. This development exposed how the grid’s interconnectivity and the use of outdated systems (such as legacy Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition and Industrial Control System equipment, as well as unpatched public-facing appliances such as older VPNs and firewalls) create major vulnerabilities, which allow one cyber intrusion to trigger cascading impacts, posing a national security risk.

The increased connectivity of critical infrastructure has improved efficiencies, but it has also opened new pathways for malicious actors, making cybersecurity essential for protecting the systems on which everyone depends. This is where competitions like the Cyber 9/12 Strategy Challenge come in. Cyber 9/12 provides students with a platform to develop and showcase their skills in policy analysis, strategic thinking, and crisis communications while critically evaluating and proposing solutions to simulated cyber crisis scenarios, preparing them for real-world challenges. It also offers valuable networking opportunities with experienced professionals in the cybersecurity community, further developing the next generation of cybersecurity leaders. Mid-career professionals who serve as judges in the competition also benefit by gaining fresh perspectives on current cyber challenges and potential solutions from students.

To gain a clearer understanding of how the New York City Cyber 9/12 Strategy Challenge is building cyber talent and crowdsourcing solutions to pressing cyber challenges, we asked teams from this year’s competition, as well as judges and organizers, about their experiences and the lessons learned.

If you were advising a new team preparing for a Cyber 9/12 competition, what strategies would you recommend?

Participating in the Cyber 9/12 competition was an invaluable experience in applying cybersecurity and policy knowledge to a complex, fast-evolving scenario. Our team learned about the importance of being thoroughly familiar with every detail of the situation and considering potential impacts from all angles, whether it be technical, political, economic, or diplomatic, to anticipate the judges’ questions and defend our recommendations.

Future competitors should be prepared to simulate the role of 24/7 cyber crisis advisors, which involves late nights of distilling urgent details into briefs within a short time frame.

Also, future competitors should focus on developing a clear, unified strategy and should practice communicating their analysis under time pressure to present a confident, well-rounded briefing. For example, teams should practice their oral briefing to get their timing down, adapt to any kinks in their presentation, get comfortable with the subject matter, and even consider alternative policy options. Teams should recognize the value of participating in this competition, as the scenario and work product we produced felt very real and reflected current challenges in cyberspace.

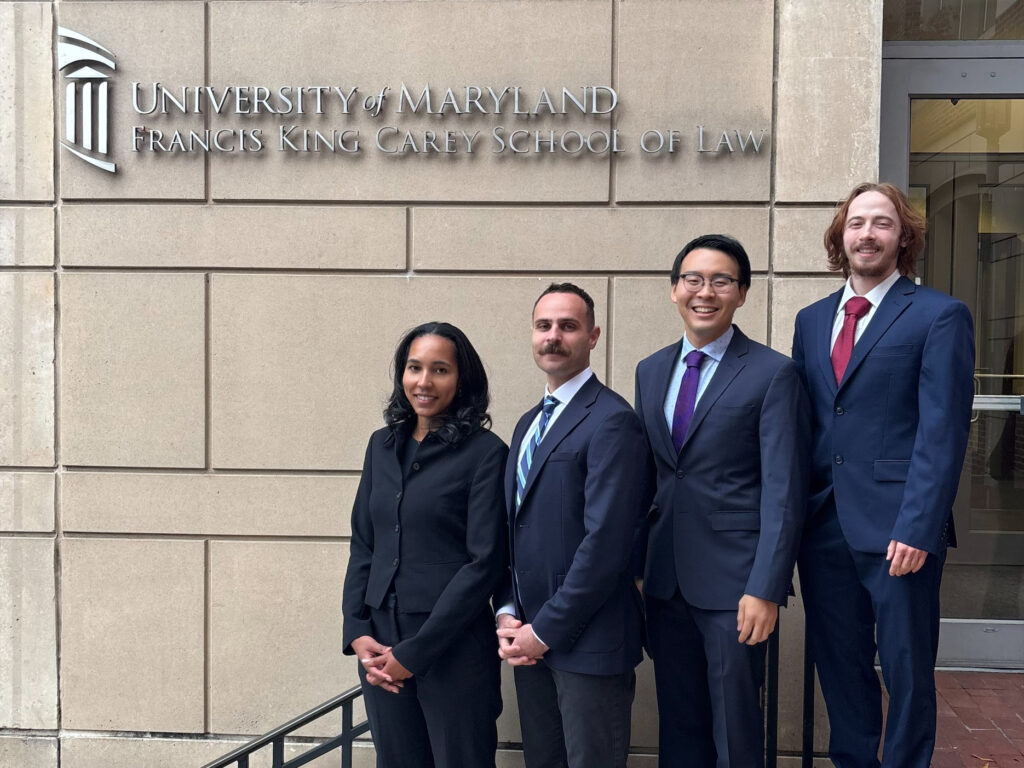

—The Cache of Amontillado of the University of Maryland

When the scenario first unfolded, what was your team’s immediate reaction, and how did you prioritize developing your policy responses?

When we were first presented with the scenario, we were shocked. We all had limited knowledge of the tensions in the South China Sea, and as we did our research and became more informed, our surprise did not wane. Our team was adamant about doing thorough research about the situation, and with our diverse backgrounds, we were able to compile a comprehensive situation report.

We prioritized our policies by focusing on a holistic perspective. We wanted to address the immediate issues and halt those that would have cascading effects, no matter how menial. My team also used a temporal approach to list our priorities. We highlighted what our immediate, short-term, and long-term goals were.

—UAlbany Cyber Danes of the University of Albany

Did the scenario force your team to rethink assumptions about the impact of cyberattacks on energy infrastructure?

While competing, our team viewed the cyberattacks on energy systems primarily through technical and operational lenses, with the attacks’ disruptions to power, fuel supply, and critical services. However, the scenario pushed us beyond that. We quickly realized how attacks on energy infrastructure can serve as strategic pressure points in geopolitical crises, shaping diplomacy, public perception, and coordination with allies and partners long before physical impacts fully unfold.

The simulation highlighted how adversaries may target energy assets not just to disable them but to create uncertainty, economic anxiety, and political friction. We found ourselves thinking about the cascading effects: emergency response strain, regional security implications, misinformation risks, and the need for clear public communication to maintain confidence and avoid panic.

Real-world examples like the Colonial Pipeline ransomware incident proved useful in grounding our assessment, reminding us that even short disruptions can trigger outsized reactions on a national scale.

Competing also reinforced lessons in decision-making during a crisis: managing incomplete information, prioritizing actions, and balancing rapid response with strategic restraint. When one teammate had unexpected technical issues during our presentation, we had to adapt on the spot, a small but fitting reminder that resilience is not only about technology; it’s about teamwork, preparation, and the ability to continue operating under pressure.

Overall, the competition broadened our understanding of cyber-energy crises as multidimensional problems that blend national security, diplomacy, technology, and public trust. It challenged us to think like policymakers, not technicians, and taught us how critical a coordinated, cross-sector strategy is in defending modern energy infrastructure.

—Rutgers Cybersecurity Club of Rutgers University

Were there any real-world events or policy frameworks that helped inform your team’s approach to the fictional scenario?

Our team’s approach was influenced by real-world events and existing policy frameworks around international cyber incidents and crisis management. When developing recommendations for the scenario, we drew on actual US government playbooks such as response protocols from the Department of Energy and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, which emphasize containment, segmentation, and rapid restoration of infrastructure during cyber emergencies.

We modeled our strategies on past major incidents like the SolarWinds and NotPetya attacks, implementing lessons learned such as network isolation and zero-trust upgrades. International cooperation frameworks—such as those used by countries in Five Eyes, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, and the Group of Seven—inspired our emphasis on cross-border intelligence sharing, joint cyber exercises, and coordinated responses with allies. We also incorporated legal structures for escalation and attribution, referencing US law and multilateral tools in our recommendations. Ultimately, our approach balanced technical resilience, diplomatic caution, and alliance building to reflect best practices from global experience with cyber crises.

—Phish Finders of Columbia University and Fordham University

What was the most complex or unexpected challenge your team faced during the simulation, and how did you navigate it?

This was our first year competing in Cyber 9/12, so we were very nervous when submitting our decision document and written brief. As a team, the most unexpected challenge was quickly adapting our strategy to the new intelligence report that dropped ahead of the semi-final round. After the first round, we received useful feedback about how we should consider international collaboration to mitigate the Volt Typhoon. Therefore, we were ecstatic to move on to the semi-finals and have a chance to apply the feedback we were provided. Our team had both technical and policy-focused members, so we were interested in weaving together our experiences in incident response and governance.

Although challenging to balance the fast-moving and multifaceted nature of policy with the intricacies of cybersecurity, we confronted this challenge head-on by discussing and rethinking existing paradigms. Through collaboration and innovative thinking, we were able to put our best foot forward at the competition.

—Cyber Cats of Northwestern University

As a Cyber 9/12 judge and alumna, what advice would you offer to future teams preparing to compete in a Cyber 9/12 competition?

Cyber 9/12 can feel a lot bigger than it actually is. Before I participated in 2021, I didn’t think I had the know-how to compete. My first inclination was to participate as a volunteer, not a competitor. I believed that I needed to have all the technical and policy expertise first before I could sign up to join a team. Now, as both a former first-place winner and three-time judge, I realize that Cyber 9/12 is, at its core, a team sport. Like on any team, success in this competition is found when a team demonstrates a diversity of skill sets and roles.

The cybersecurity industry works like this, too—it is an amalgamation of technicians, engineers, communicators, policymakers, and program managers. Starting with the right team will make it possible to break up the competition based on each team member’s unique skill sets.

Looking at the strategy as an accumulation of its smaller parts will help a competitor weave together the narrative and then coherently deliver the story to the judges. For example, teams should consider delegating the technical risk factors to the computer science student to analyze and present and having the communicator or marketer present opening and closing remarks for the judges. At the end of the day, the most prepared teams are the ones who perform together the best.

—Danielle Neftin Errant, Cyber 9/12 Strategy Challenge judge and alumna; senior associate at JP Morgan and Chase

In your view, what specific skills are becoming most essential for future cyber leaders, and how can universities, faculty, and mentors better prepare and support students to develop those skills through experiential learning opportunities like Cyber 9/12?

One of the most essential, and often overlooked, skills for future cyber leaders is the ability to discern what they don’t know. Exercises like Cyber 9/12 sharpen that discipline by forcing students to make policy recommendations under pressure, with the perceived weight of national-level consequences attached.

In real decision environments, senior leaders want three things: first, “the situation” and what is known to be fact; second, “the analysis,” which is an interpretation of what those facts mean; and third, “the known unknown,” covering what is not known, which often defines the uncertainty that must be weighed in the decision making process.

Academic settings rarely expose students to that dynamic, yet it mirrors how decisions are actually made by senior leaders in geopolitics and national security.

Universities, faculty, and mentors can better prepare students by creating experiential learning environments like those created in Cyber 9/12 that reward discernment as much as technical precision. When students learn to separate fact from assumption, truth from influence, and confidence from overconfidence, they develop the judgment needed to recognize misinformation, foreign manipulation, and cognitive traps that risk leading to strategic miscalculation. I was fortunate to serve as a judge for two of the top three teams in the New York City competition, and one commonality between them stood out: both teams excelled at diagnosing the situation and clearly articulating what they knew to be true, what was unconfirmed (or, in some cases, possibly conjecture from biased sources), and what they did not know. That level of clarity under pressure reflects exactly the kind of discernment and communication that defines effective decision-making in cyber leadership.

—Fred Bailey, Cyber 9/12 Strategy Challenge judge; managing director at Gideon Arktos

Having transitioned from a competitor to an organizer, what insights have you gained about how scenario design and event structure can best prepare students to think critically under real-world policy and technical pressure?

Transitioning from a competitor to an organizer for Cyber 9/12 completely reshaped my understanding of what the challenge is meant to teach. When I was competing in March 2025, my team was hyper focused on crafting the best decision documents, reviewing and analyzing various frameworks that could guide our response, and anticipating judges’ questions. But once I became an organizer, I realized that the ethos of the competition does not lie in defending one’s recommendations, but instead, it is a test to see how critically one’s team can think on their feet, adapt in a fast-paced environment, and collaborate. The competition is ultimately about making consequential choices in times of uncertainty, and as a student, there’s no better skill to practice than that.

Moreover, the challenge is a logistical feat that few participants have ever seen. I have a deep appreciation for just how much effort it takes to run the show. What looks seamless from the outside (the timed intelligence reports, the brilliant judges, the smooth transitions over Zoom) is, in reality, the product of relentless coordination.

When I speak to Cyber 9/12 alumni, what strikes me most is how many describe the competition as life-changing. They talk about how it opened doors by helping them land jobs, navigate complex policy roles, and even simply think more critically in their professional lives. I can affirm the same now—Cyber 9/12 really is life-changing.

—Amiya Kumar, president, Digital and Cyber Group, Columbia University

About Cyber 9/12

The Cyber Statecraft Initiative’s Cyber 9/12 Strategy Challenge is an annual cyber policy and strategy competition where students from across the globe compete in developing policy recommendations tackling a fictional cyber catastrophe.

Explore the Program

The ’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative, part of the Technology Programs, works at the nexus of geopolitics and cybersecurity to craft strategies to help shape the conduct of statecraft and to better inform and secure users of technology.

Image: Photo by Benjamin Ashton on Unsplash