If someone today wanted to build something like a new Hubble, it would make sense to think of years of reports, reviews and committees before the first piece of hardware is even manufactured. However, that logic has just been broken with an unexpected announcement: Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google, and his wife Wendy have put their own money on the table to promote not one, but four telescopes, including a large-scale space observatory.

The move not only challenges the sector’s inertia, but raises a question deeper than budget or technology: what exactly is a former Silicon Valley executive pursuing by wading into the heart of modern astronomy. This is a project promoted by the Schmidt Observatory System, it seeks to cover everything from the deep sky to the detailed study of transient phenomena.

A change of model. Currently, telescopes are generally in the hands of public agencies and academic consortia. Building ever-larger mirrors and then putting instruments into orbit turned astronomy into a matter of national budgets. The Schmidts’ entry into this arena suggests that, with new technologies and another way to finance risk, that historic balance could be starting to shift again.

Risk, speed and open science. The approach behind the observatory system is not to compete with space agencies, but to cover the space left by their own processes, which are long, conservative and highly conditioned by public budgets. The Schmidts seek to finance concepts that have already been imagined by the scientific community, but that rarely overcome the barrier of official financing due to their level of risk or the deadlines they require.

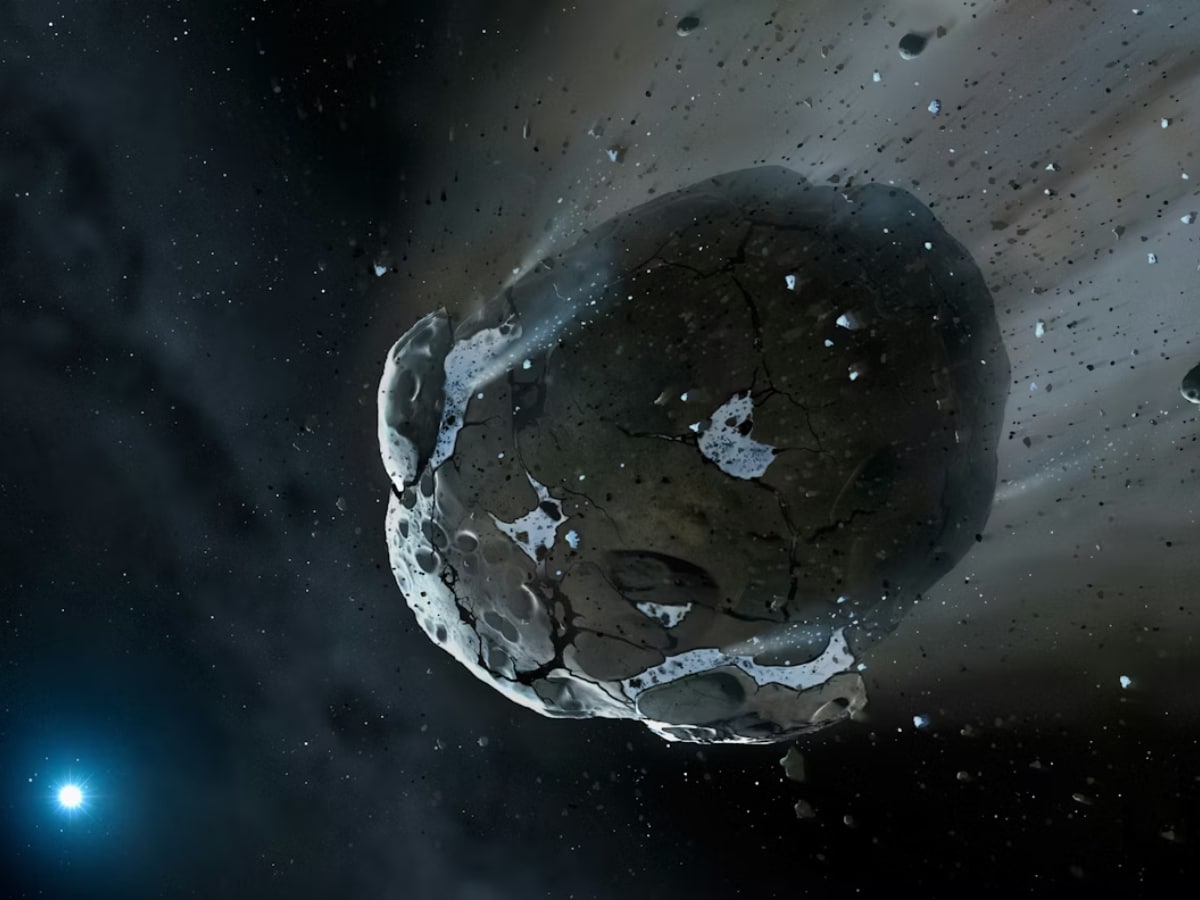

The piece that gives meaning to the whole and that really makes the difference is Lazuli, the only one of the four projects that will leave Earth. It aims to cover a wide range of science, from transient events lasting minutes or hours to the detailed study of exoplanets, with a level of flexibility that large public observatories cannot always offer.

Further, more agile. One of the clearest breaks between Lazuli and Hubble is where it will operate and how. While NASA’s telescope orbits about 500 kilometers from Earth, Lazuli will be placed much further away, in an elliptical orbit that should give it a clearer view and allow for fast and continuous data linking.

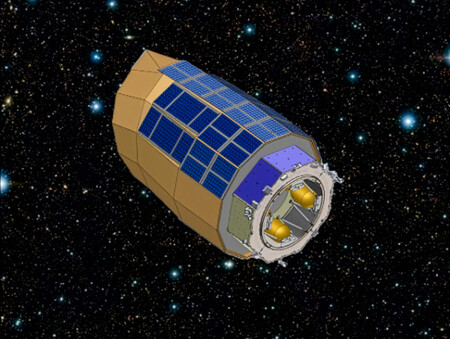

Lazuli Space Observatory

In the official description, Schmidt Sciences frames this operation in a “lunar-resonant” orbit. Added to this is a larger mirror, 3.1 meters compared to Hubble’s 2.4 meters, and an observation philosophy designed to react quickly to unexpected phenomena.

One platform, several instruments. Lazuli is designed as a unique platform that integrates three instruments designed to cover everything from wide-field observations to the detailed study of exoplanets and transient phenomena.

- Wide-field optical imager with high cadence for photometric time series, 30′×15′ field of view and filters between 300 and 1000 nm

- Integral field spectrograph continuously covering 400–1700 nm, optimized for stable spectrophotometry and rapid sorting

- High contrast coronagraph to directly observe exoplanets and circumstellar environments, with contrasts of 10⁻⁸ and up to 10⁻⁹ after processing

The era of array telescopes. Argus, DSA and LFAST are not traditional telescopes, but distributed systems that take advantage of recent advances in computing, storage and automated analysis. Instead of concentrating everything in a single structure, they distribute the collection of light or radio signals among tens or thousands of modules that are then digitally synchronized. This modularity aims to accelerate deployments and opens the door to observing the sky almost in real time, something fundamental for the astronomy of fleeting events.

Render of the Argus Array (left), Deep Synoptic Array (right)

Argus Array will bring together 1,200 optical telescopes in Texas to observe the northern sky almost continuously, with the idea of being able to “rewind” what happened minutes or hours before an event such as a supernova. DSA, in Nevada and under the direction of Caltech, will deploy 1,600 radio antennas to map more than a billion sources and update its view of the sky every fifteen minutes. LFAST, for its part, will be installed in Arizona as a system of 20 80-centimeter mirrors aimed at large-aperture spectroscopy and the search for biosignatures, with a prototype planned for mid-2026.

What the Schmidts have launched is, at its core, an experiment on the scientific system itself. Lazuli and his three colleagues on land aim to show that it is possible to build large-scale observatories more quickly and with an openness of data that does not always fit into traditional models. Whether that vision materializes will depend on factors yet to be determined, such as the final contractors, real costs or the feasibility of the schedules, but if it goes well, the impact will not only be measured in new discoveries, but in a new way of deciding what science is done.

Imágenes | Village Global | Schmidt Observatory System

In WorldOfSoftware | China has just resolved one of the biggest doubts about going to Mars with the birth of six space mice