In addition to denying X and xAI’s demand, the judge also decried the case’s excessive discovery requests and disputes. Here are the details.

Court’s patience wears thin

Last year, X and xAI filed a lawsuit against Apple and OpenAI, following Elon Musk’s claim that their partnership to integrate ChatGPT into iOS was preventing competing AI apps from succeeding in the App Store. The accusation was promptly debunked by X’s own users.

Following Apple and OpenAI’s failed attempts to dismiss the lawsuit, the case moved into discovery, the pretrial phase in which the parties exchange documents and evidence.

In the weeks that followed, X and xAI issued multiple motions to compel Apple and OpenAI to hand over troves of documents, while also sending document requests to at least eight foreign companies behind so-called “super apps.”

In one of these motions, X and xAI asked the court to force Apple and OpenAI to hand over what is loosely referred to as “source code”.

Many documents related to this dispute have yet to be made public. But in essence, based on documents that have been made public, OpenAI argued that there are technical aspects that make it impossible for Grok to be integrated into Apple Intelligence.

This, in turn, made X and xAI ask for “source code” in an attempt to disprove that argument.

Which brings us to today. In a decision signed by U.S. Magistrate Judge Hal R. Ray Jr., the request for source code was denied because the court found it was neither relevant to the antitrust claims, nor proportional to the needs of the case.

From the decision:

The Court concludes that OpenAI’s source code is not relevant to Plaintiffs’ claims and is not within the scope of discovery under Rule 26. […] Although OpenAI’s source code certainly would be of great interest to Plaintiffs, Rule 26 does not require its disclosure. Before the Court would order production of any party’s sensitive, confidential information such as the source code at issue here, the requesting party would have to show that it had attempted to gather the necessary information for developing the claim or defense underlying its request without reference to that highly sensitive information. Plaintiffs have not done so here, though they still have ample opportunities to develop evidence in discovery regarding the feasibility of integrating Grok into Apple iPhones and other products without having unfettered access to OpenAI’s source code.

In other words, while the court knows that X and xAI would love to see OpenAI’s proprietary code, it also believes that there are less intrusive ways to try to disprove OpenAI’s technical claims as to why Grok can’t be integrated into iOS.

The judge also pointed out that “while this case is not yet five months old, the docket contains more than one hundred thirty-five entries and is replete with countless discovery disputes,” underscoring its impatience with what it sees as X and xAI’s overly aggressive and disproportionate discovery tactics.

The judge didn’t stop there, as he also rejected X and xAI’s implication that if OpenAI refused to produce its source code, it would be admitting that Grok could indeed be integrated into Apple Intelligence:

“[…] Plaintiffs present their competitor OpenAI with a choice: hand over its most sensitive proprietary information or admit that Grok could have been integrated into the iPhone operating system. The Court does not order OpenAI to produce its source code. […] And even if the source code requested were potentially relevant, which the Court does not find, its production is not proportional to the needs of the case.”

Today’s decision isn’t the only recent setback for X and xAI in this case. Last week, South Korea’s government denied the companies’ request for documents from the Kakao super app, also citing that the scope of the request was disproportionate and overly broad.

What’s your take on X and xAI’s strategy? Let us know in the comments.

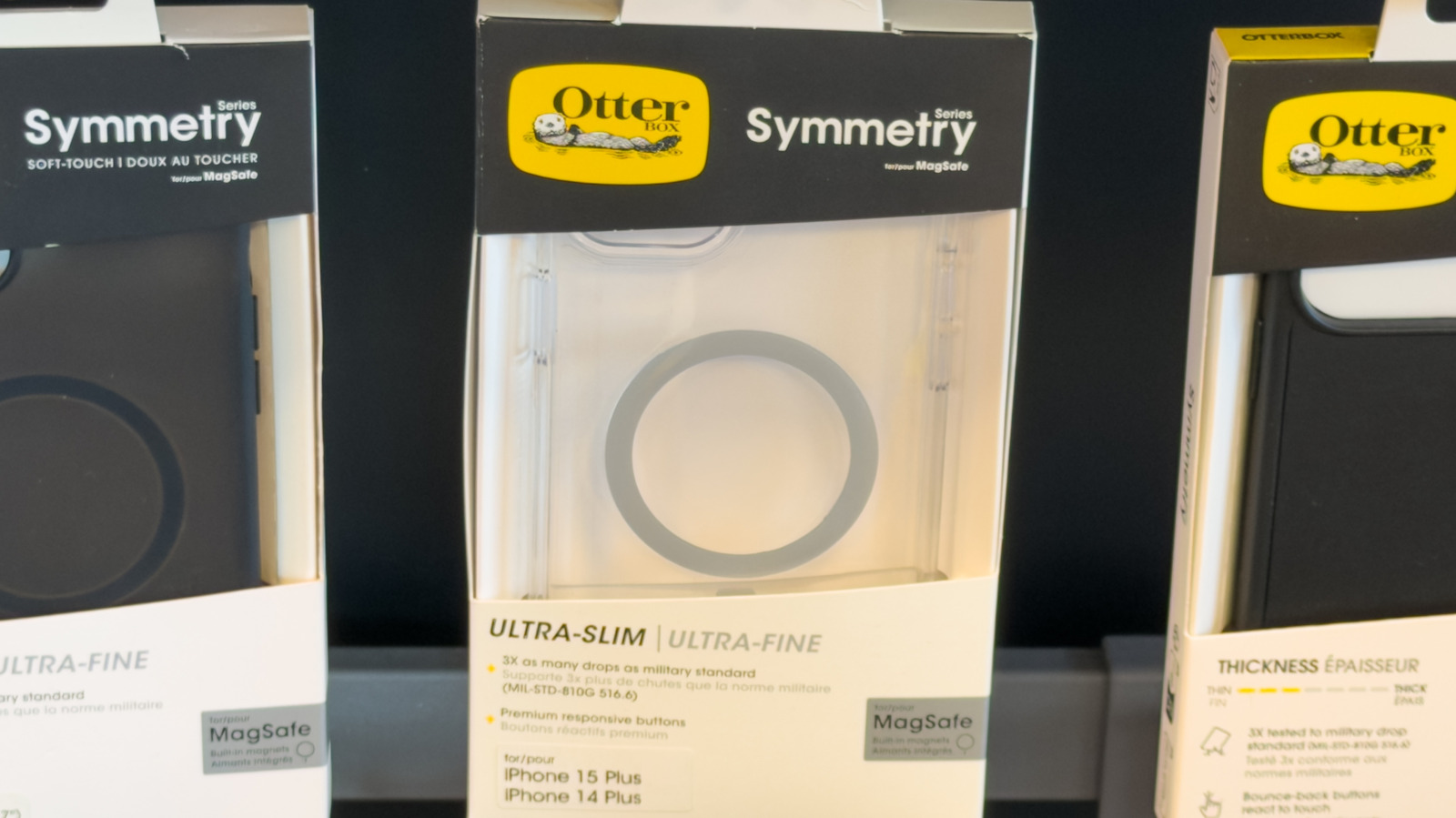

Accessory deals on Amazon

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.