GetEquity, a Nigerian fintech platform that functions as a digital marketplace for private capital, began in the venture capital boom in 2021. Its mission to democratise venture capital for everyday Nigerians felt not just timely, but inevitable. Retail investors filled a $50,000 startup round in an hour, and growth charts climbed.

But by 2023, the narrative had fractured. A historic naira devaluation and a continent-wide venture capital freeze threatened to erase the blueprint. GetEquity’s startup journey would not be about scaling a dream, but engineering a survival, one that would force it to abandon its original thesis and discover a more fundamental truth about the African investment landscape.

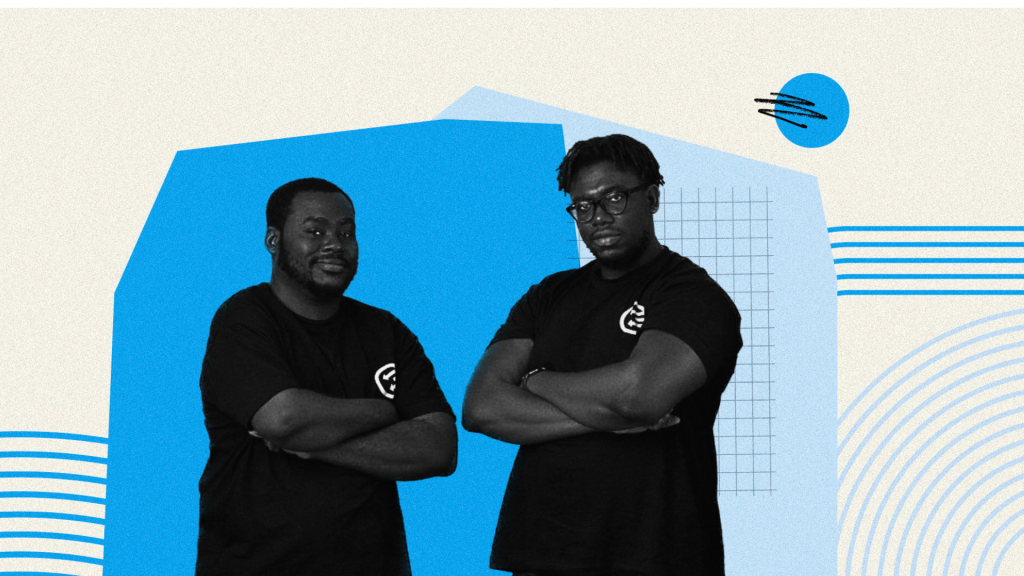

Day 1: The accidental neighbours

Jude Dike and Temitope Ekundayo first connected online in 2020. Dike, a blockchain engineer, was trying to build an exchange for startup investments. Ekundayo was working on a business intelligence tool. They were chasing different problems, access to market data and startup fundraising, but saw the same market gap.

After speaking virtually for months, they decided to meet.

“I asked Jude for his address,” Ekundayo recounts. “He tells me, and I’m like, ‘You’re my neighbour.’” They lived on the same street.

That serendipity cemented their partnership. Joining forces, they merged ideas and entered the Mozilla Builders Accelerator, an incubator program that focused on technologies that shaped the internet, in 2020, building the first version of GetEquity.

The premise was bold: to let retail investors fund African startups the same way people participated in crypto token sales. The company secured a $100,000 pre-seed from Greenhouse Capital in early 2021 and launched that July.

The timing seemed perfect.

“We launched in 2021, and that was a really good year; we were growing at 15 to 20% month on month,” Dike says.

Their first deal, a $50,000 raise for a startup, was filled in under an hour. It was a venture capital fantasy. But in the world of startups, the story is never a straight line.

The early success of 2021 masked a growing structural problem. GetEquity had built what Dike calls “technical hubris”: a suite of products like Employee Stock Option (ESOP) portals and stock management tools.

“We built a tool, but really, it’s not what people would want at that time,” Ekundayo admits. It was a ‘vitamin,’ not a ‘painkiller.’ When the naira devalued in 2023, the risk of funding US-based assets with local currency became a hole they couldn’t ignore.

“2023 was our worst year ever,” Dike states bluntly. The platform was built for a venture ecosystem that had suddenly evaporated. Revenue from startup deals dwindled as the cost of everything soared. Their original thesis was crumbling.

It was a moment of brutal clarity that many founders face. They had built a sophisticated engine, but the fuel—VC deals and investor appetite for them—was gone. They had to find a new fuel or the machine would stop. Their participation in the 2023 Techstars accelerator, an ARM Labs Lagos program, provided the framework for a desperate experiment.

Day 500:

Forced to look beyond startups, the team began testing new asset classes with their user base. They started small: a trade note, a debt note for motorcycle financing. The results were encouraging but modest. The breakthrough came with an idea so conventional that, in its context, it was radical: commercial papers.

These short-term debt instruments from large, blue-chip corporations are staples of traditional finance but were largely inaccessible to the average Nigerian investor. In early 2024, they ran a test with a Dangote Sugar Refinery commercial paper. They estimated interest of about ₦10.5 million ($7,400). The result stunned them.

“By the first day we put that out, we had done about 4 million. By the fifth day, we had crossed 27 million,” Dike explains. The product-market fit was explosive. By the end of 2024, they had facilitated nearly ₦300 million ($200,000) in commercial paper investments. The experiment was no longer an experiment; it was their new business.

This pivot changed everything. Partnering with established asset managers who sourced and vetted these deals meant GetEquity no longer needed a large internal due diligence team. The company had to restructure, painfully. In 2024, GetEquity laid off 40% of its workforce after a shift in operational strategy.

“It was an amicable departure,” Ekundayo explains, noting that the staff themselves had hinted at downsizing because they saw the roles becoming obsolete as the model shifted.

The layoff, coupled with the capital-light partnership model, achieved a critical goal: profitability. GetEquity had traded the high-risk, high-cost VC model for a leaner, more sustainable brokerage engine.

The pivot also revealed a hidden superpower. The digital infrastructure they’d built for startup syndicates, the portals, the dashboards, the investment flows, was perfectly repurposable.

“GetEquity is actually a customer of its own product,” Dike notes, using its own platform to distribute deals to its retail community. They had accidentally built a white-label solution for the entire private capital market.

Day 1000:

For GetEquity, the breakneck growth of 2021 has been traded for calculated scaling from a position of operational efficiency. The company is now working to formalise its new path, seeking a digital asset custodian licence from Nigeria’s Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to solidify its standing. This move aligns with a key lesson from their turnaround, as Dike notes, “Your regulators actually want to see you thrive.”

GetEquity’s focus is on the Nigerian market; Dike and Ekundayo have shelved expansion plans for Kenya. Their roadmap involves introducing more private capital asset classes with asset managers like ARM.

Although built for one purpose, the company has found a more sustainable fuel, and the founders’ mission has shifted from disrupting the system to becoming a vital, digitised part of it.