:::info

Authors:

- Karan Singhal (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Shekoofeh Azizi (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Tao Tu (Google Research, DeepMind)

- S. Sara Mahdavi (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Jason Wei (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Hyung Won Chung (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Nathan Scales (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Ajay Tanwani (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Heather Cole-Lewis (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Stephen Pfohl (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Perry Payne (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Martin Seneviratne (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Paul Gamble (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Chris Kelly (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Nathaneal Schärli (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Aakanksha Chowdhery (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Philip Mansfield (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Blaise Agüera y Arcas (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Dale Webster (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Greg S. Corrado (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Yossi Matias (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Katherine Chou (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Juraj Gottweis (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Nenad Tomasev (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Yun Liu (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Alvin Rajkomar (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Joelle Barral (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Christopher Semturs (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Alan Karthikesalingam (Google Research, DeepMind)

- Vivek Natarajan (Google Research, DeepMind

:::

Large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated impressive capabilities in natural language understanding and generation, but the quality bar for medical and clinical applications is high. Today, attempts to assess models’ clinical knowledge typically rely on automated evaluations on limited benchmarks. There is no standard to evaluate model predictions and reasoning across a breadth of tasks. To address this, we present MultiMedQA, a benchmark combining six existing open question answering datasets spanning professional medical exams, research, and consumer queries; and HealthSearchQA, a new free-response dataset of medical questions searched online. We propose a framework for human evaluation of model answers along multiple axes including factuality, precision, possible harm, and bias.

In addition, we evaluate PaLM (a 540-billion parameter LLM) and its instruction-tuned variant, Flan-PaLM, on MultiMedQA. Using a combination of prompting strategies, Flan-PaLM achieves state-of-the-art accuracy on every MultiMedQA multiple-choice dataset (MedQA, MedMCQA, PubMedQA, MMLU clinical topics), including 67.6% accuracy on MedQA (US Medical License Exam questions), surpassing prior state-of-the-art by over 17%. However, human evaluation reveals key gaps in Flan-PaLM responses. To resolve this we introduce instruction prompt tuning, a parameter-efficient approach for aligning LLMs to new domains using a few exemplars. The resulting model, Med-PaLM, performs encouragingly, but remains inferior to clinicians.

We show that comprehension, recall of knowledge, and medical reasoning improve with model scale and instruction prompt tuning, suggesting the potential utility of LLMs in medicin

This paper is available on arxiv under CC by 4.0 Deed (Attribution 4.0 International) license.

n

e. Our human evaluations reveal important limitations of today’s models, reinforcing the importance of both evaluation frameworks and method development in creating safe, helpful LLM models for clinical applications.

1 Introduction

Medicine is a humane endeavor where language enables key interactions for and between clinicians, researchers, and patients. Yet, today’s AI models for applications in medicine and healthcare have largely failed to fully utilize language. These models, while useful, are predominantly single-task systems (e.g., classification, regression, segmentation), lacking expressivity and interactive capabilities [21, 81, 97]. As a result, there is a discordance between what today’s models can do and what may be expected of them in real-world clinical workflows [42, 74].

Recent advances in large language models (LLMs) offer an opportunity to rethink AI systems, with language as a tool for mediating human-AI interaction. LLMs are “foundation models” [10], large pre-trained AI systems that can be repurposed with minimal effort across numerous domains and diverse tasks. These expressive and interactive models offer great promise in their ability to learn generally useful representations from the knowledge encoded in medical corpora, at scale. There are several exciting potential applications of such models in medicine, including knowledge retrieval, clinical decision support, summarisation of key findings, triaging patients’ primary care concerns, and more.

However, the safety-critical nature of the domain necessitates thoughtful development of evaluation frameworks, enabling researchers to meaningfully measure progress and capture and mitigate potential harms. This is especially important for LLMs, since these models may produce generations misaligned with clinical and societal values. They may, for instance, hallucinate convincing medical misinformation or incorporate biases that could exacerbate health disparities.

To evaluate how well LLMs encode clinical knowledge and assess their potential in medicine, we consider medical question answering. This task is challenging: providing high-quality answers to medical questions requires comprehension of medical context, recall of appropriate medical knowledge, and reasoning with expert information. Existing medical question answering benchmarks [33] are often limited to assessing classification accuracy or automated natural language generation metrics (e.g., BLEU [67]), and do not enable the detailed analysis required for real-world clinical applications. This creates an unmet need for a broad medical question answering benchmark to assess LLMs’ response factuality, use of expert knowledge in medical and scientific reasoning, helpfulness, precision, health equity, and potential harm to humans accepting model outputs as facts.

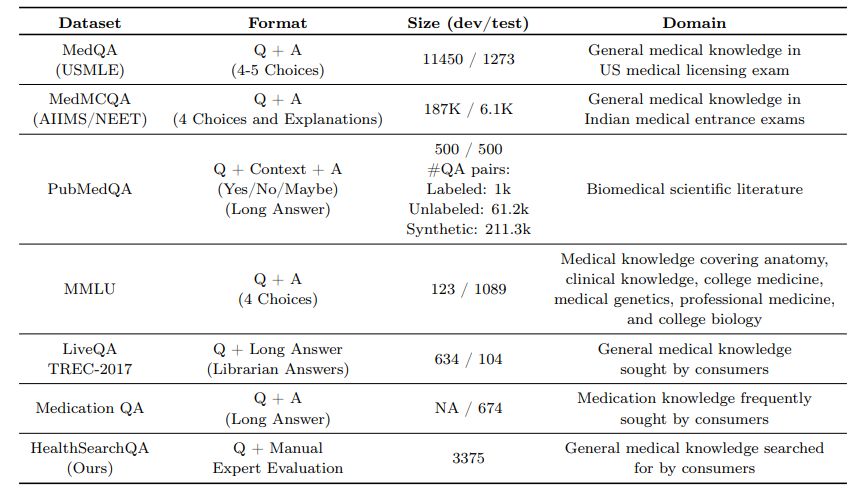

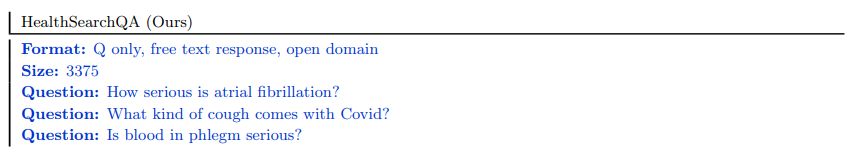

To address this, we curate MultiMedQA, a benchmark comprising seven medical question answering datasets, including six existing datasets: MedQA [33], MedMCQA [64], PubMedQA [34], LiveQA [1], MedicationQA [2], and MMLU clinical topics [29]. We newly introduce the seventh dataset, HealthSearchQA, which consists of commonly searched health questions.

To assess LLMs using MultiMedQA, we build on PaLM, a 540-billion parameter LLM [14], and its instruction-tuned variant Flan-PaLM [15]. Using a combination of few-shot [12], chain-of-thought (CoT) [91], and self-consistency [88] prompting strategies, Flan-PaLM achieves state-of-the-art (SOTA) performance on MedQA, MedMCQA, PubMedQA, and MMLU clinical topics, often outperforming several strong LLM baselines by a significant margin. On the MedQA dataset comprising USMLE questions, FLAN-PaLM exceeds previous SOTA by over 17%.

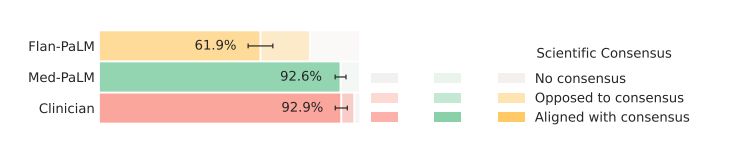

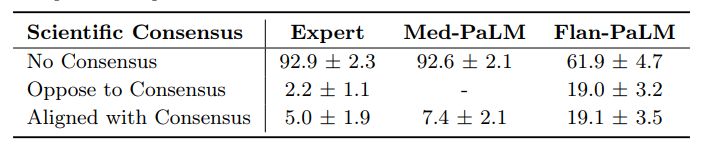

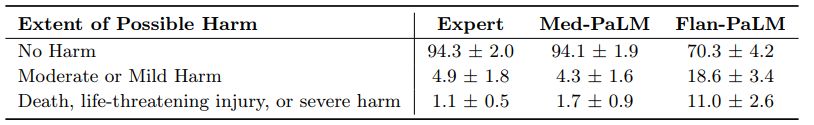

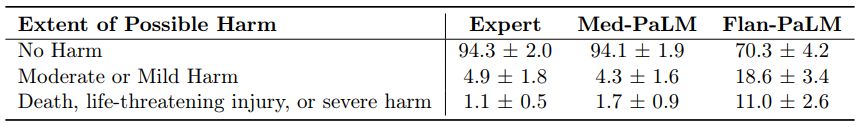

Despite Flan-PaLM’s strong performance on multiple-choice questions, its answers to consumer medical questions reveal key gaps. To resolve this, we propose instruction prompt tuning, a data- and parameter-efficient alignment technique, to further adapt Flan-PaLM to the medical domain. The resulting model, Med-PaLM, performs encouragingly on the axes of our pilot human evaluation framework. For example, a panel of clinicians judged only 61.9% of Flan-PaLM long-form answers to be aligned with scientific consensus, compared to 92.6% for Med-PaLM answers, on par with clinician-generated answers (92.9%). Similarly, 29.7% of Flan-PaLM answers were rated as potentially leading to harmful outcomes, in contrast with 5.8% for Med-PaLM, comparable with clinician-generated answers (6.5%).

While these results are promising, the medical domain is complex. Further evaluations are necessary, particularly along the dimensions of fairness, equity, and bias. Our work demonstrates that many limitations must be overcome before such models become viable for use in clinical applications. We outline some key limitations and directions of future research in our study.

Our key contributions are summarized below:

- Approaches for evaluation of LLMs in medical question answering

– Curation of HealthSearchQA and MultiMedQA We introduce HealthSearchQA, a dataset of 3375 commonly searched consumer medical questions. We present this dataset alongside six other existing open datasets for medical question answering, spanning medical exam, medical research, and consumer medical questions, as a diverse benchmark to assess the clinical knowledge and question answering capabilities of LLMs (see Section 3.1).

– Pilot framework for human evaluation We pilot a framework for physician and lay user evaluation to assess multiple axes of LLM performance beyond accuracy on multiple-choice datasets. Our evaluation assesses answers for agreement with scientific and clinical consensus, likelihood and possible extent of harm, reading comprehension, recall of relevant clinical knowledge, manipulation of knowledge via valid reasoning, completeness of responses, potential for bias, relevance, and helpfulness (see Section 3.2).

- State-of-the-art results on medical question answering benchmarks On the MedQA, MedMCQA, PubMedQA and MMLU clinical topics datasets, FLAN-PaLM achieves SOTA performance via a com-bination of prompting strategies, surpassing several strong LLM baselines. Specifically, we reach 67.6% accuracy on MedQA (more than 17% above prior SOTA), 57.6% on MedMCQA, and 79.0% on PubMedQA (see Section 4).

- Instruction prompt tuning to align LLMs to the medical domain We introduce instruction prompt tuning, a simple, data- and parameter-efficient technique for aligning LLMs to the safety-critical medical domain (see Section 3.3.3). We leverage this to build Med-PaLM, an instruction prompt-tuned version of Flan-PaLM specialized for the medical domain. Our human evaluation framework reveals limitations of Flan-PaLM in scientific grounding, harm, and bias. However, Med-PaLM significantly reduces the gap (or even compares favorably) to clinicians on several of these axes, according to both clinicians and lay users (see Section 4.5).

- Key limitations of LLMs revealed through our human evaluation While our results demonstrate the potential of LLMs in medicine, they also suggest several critical improvements are necessary in order to make these models viable for real-world clinical applications. We outline future research directions and mitigation strategies to address these challenges (see Section 6).

2 Related work

Large language models (LLMs) Over the past few years, LLMs have shown impressive performance on natural language processing (NLP) tasks [12, 14, 15, 30, 69, 70, 73, 89, 91, 99]. They owe their success to scaling up the training of transformer-based models [84]. It has been shown that model performance and data-efficiency scales with model size and dataset size [37]. LLMs are often trained using self-supervision on large scale, using general-purpose text corpi such as Wikipedia and BooksCorpus. They have demonstrated promising results across a wide range of tasks, including tasks that require specialized scientific knowledge and reasoning [17, 29]. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of these LLMs is their in-context few-shot abilities, which adapt these models to diverse tasks without gradient-based parameter updates [12, 40, 43, 89]. This allows them to rapidly generalize to unseen tasks and even exhibit apparent reasoning abilities with appropriate prompting strategies [14, 47, 79, 91].

Several studies have shown that LLMs have the capacity to act as implicit knowledge bases [29, 35, 79]. However, there is a significant risk of these models producing hallucinations, amplifying social biases present in their training data, and displaying deficiencies in their reasoning abilities. To examine the current limitations of LLMs and to quantify the large gap between human and LLM language capabilities, BIG-bench was introduced as a community-wide initiative to benchmark on tasks that were believed at time of publication to be beyond the capabilities of current language models [78].

LLMs for science and biomedicine Recent studies, such as SciBERT [5], BioNLP [46], BioMegatron [76], BioBERT [44], PubMedBERT [25], DARE [66], ScholarBERT [31], and BioGPT [56], have demonstrated the effectiveness of using curated scientific and biomedical corpora for both discriminative and generative language modeling. These models, although promising, are typically small in scale and scope compared to LLMs such as GPT-3 [12] and PaLM [14]. While the medical domain is challenging, specific proposals for LLMs have already included examples as varied as augmenting non-critical clinical assessments to summarisation of complex medical communications [3, 41, 75].

The closest precedents to our work are Taylor et al. [79], who introduced a LLM for science named Galactica, and Liévin et al. [50], who studied the reasoning capability of LLMs in the medical question answering context. In particular, Liévin et al. [50] used Instruct GPT-3, an instruction-tuned LLM [63], and applied chain-of-thought prompting [91] on top to improve the results on the MedQA, MedMCQA, and PubMedQA datasets.

3 Methods

Here we describe in detail:

- Datasets: the MultiMedQA benchmark for assessment of LLMs in medical question answering.

- Framework for human evaluation: a rating framework for evaluation of model (and clinician) answers by clinicians and laypeople.

- Modeling: Large language models (LLMs) and the methods used to align them to requirements of the medical domain in this study.

3.1 Datasets

To assess the potential of LLMs in medicine, we focused on medical question answering. Answering medical questions requires reading comprehension skills, ability to accurately recall medical knowledge, and manipula-tion of expert knowledge. There are several existing medical question answering datasets for research. These include datasets that assess professional medical knowledge such as medical exam questions [33, 64], questions that require medical research comprehension skills [34], and questions that require the ability to assess user intent and provide helpful answers to their medical information needs [1, 2].

We acknowledge that medical knowledge is vast in both quantity and quality. Existing benchmarks are inherently limited and only provide partial coverage of the space of medical knowledge. Nonetheless, bringing together a number of different datasets for medical question answering enables deeper evaluation of LLM knowledge than multiple-choice accuracy or natural language generation metrics such as BLEU. The datasets we grouped together probe different abilities – some are multiple-choice questions while others require long-form answers; some are open domain (where questions are answered without limiting available information to a pre-specified source) while others are closed domain (where questions are answered by retrieving content from associated reference text) and come from different sources. There has been extensive activity in the field of medical question answering over recent years and we refer to [33] for a comprehensive summary of medical question answering datasets.

3.1.1 MultiMedQA – A benchmark for medical question answering

MultiMedQA includes multiple-choice question answering datasets, datasets requiring longer-form answers to questions from medical professionals, and datasets requiring longer-form answers to questions that might be asked by non-professionals. These include the MedQA [33], MedMCQA [64], PubMedQA [34], LiveQA [1], MedicationQA [2] and MMLU clinical topics [29] datasets. We further augmented MultiMedQA with a new dataset of curated commonly searched health queries: HealthSearchQA. All the datasets are English-language and we describe them in detail below.

These datasets vary along the following axes:

- Format: multiple-choice vs. long-form answer questions

- Capabilities tested: e.g., assessing the recall of medical facts in isolation vs. assessing medical reasoning capabilities in addition to recall of facts

- Domain: open domain vs. closed domain questions

- Question source: from professional medical exams, medical research, or consumers seeking medical information

- Labels and metadata: presence of labels or explanations and their sources

While MedMCQA, PubMedQA, LiveQA, and MedicationQA provide reference long-form answers or explana-tions, we do not use them in this work. Firstly, the reference answers are not coming from consistent sources across the different datasets. Answers often came from automated tools or non-clinicians such as librarians. The construction of the reference answers and explanations in these pioneering datasets was not optimized for holistic or comprehensive assessments of long-answer quality, which renders them suboptimal for use as a “ground truth” against which to assess LLMs using automated natural language metrics such as BLEU. To alleviate this, as discussed in Section 4.5, we obtained a standardized set of responses from qualified clinicians to a subset of the questions in the benchmark. Secondly, given the safety-critical requirements of the medical domain, we believe it is important to move beyond automated measures of long-form answer generation quality using metrics such as BLEU to those involving more nuanced human evaluation frameworks such as the one proposed in this study.

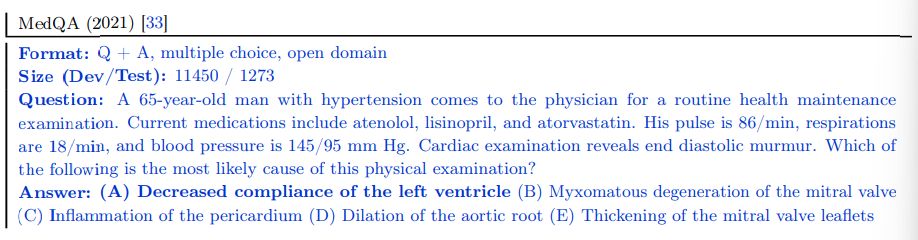

MedQA (USMLE) The MedQA dataset [33] consists of US Medical License Exam (USMLE) style questions, which were obtained with a choice of 4 or 5 possible answers from the National Medical Board Examination in the USA. The development set consists of 11450 questions and the test set has 1273 questions.

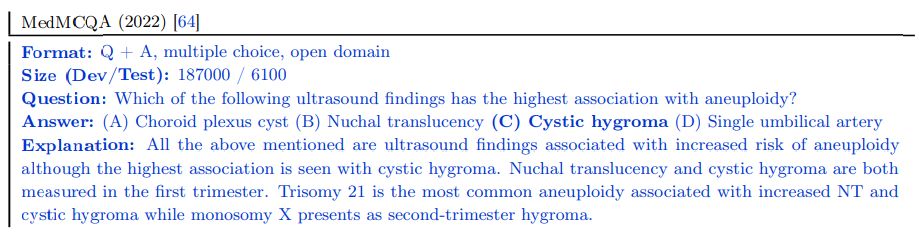

MedMCQA The MedMCQA dataset consists of more than 194k 4-option multiple-choice questions from Indian medical entrance examinations (AIIMS/NEET) [64]. This dataset covers 2.4k healthcare topics and 21 medical subjects. The development set is substantial, with over 187k questions.

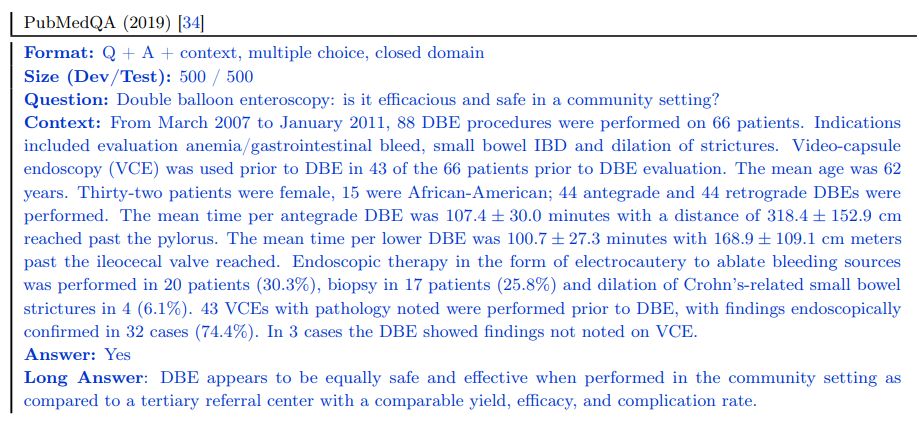

PubMedQA The PubMedQA dataset [34] consists of 1k expert labeled question answer pairs where the task is to produce a yes/no/maybe multiple-choice answer given a question together with a PubMed abstract as context. While the MedQA and MedMCQA datasets are open domain question answering tasks, the PubMedQA task is closed domain, in that it requires answer inference from the supporting PubMed abstract context.

MMLU “Measuring Massive Multitask Language Understanding” (MMLU) [29] includes exam questions from 57 domains. We selected the subtasks most relevant to medical knowledge: “anatomy”, “clinical knowledge”, “college medicine”, “medical genetics”, “professional medicine”, and “college biology”. Each MMLU subtask contains multiple-choice questions with four options, along with the answers.

LiveQA The LiveQA dataset [1] was curated as part of the Text Retrieval Challenge (TREC) 2017. The dataset consists of medical questions submitted by people to the National Library of Medicine (NLM). The dataset also consists of manually collected reference answers from trusted sources such as the National Institute of Health (NIH) website.

MedicationQA The MedicationQA dataset [2] consists of commonly asked consumer questions about medications. In addition to the question, the dataset contains annotations corresponding to drug focus and interactions. Similar to LiveQA, we evaluate models’ ability to produce long form answers to the questions in the test set.

HealthSearchQA We curated our own additional dataset consisting of 3375 commonly searched consumer questions, referred to as “HealthSearchQA”. The dataset was curated using seed medical conditions and their associated symptoms. We used the seed data to retrieve publicly-available commonly searched questions generated by a search engine, which were displayed to all users entering the seed terms. We publish the dataset as an open benchmark for consumer medical question answering and hope this will be a useful resource for the community, as a dataset reflecting real-world consumer concerns.

While MultiMedQA allows us to probe the medical question answering capabilities of LLMs along multiple axes, we acknowledge that it is not exhaustive. We plan to expand the benchmark to other relevant datasets, such as those probing question answering ability from electronic medical records [65] or those requiring pre-clinical biomedical knowledge [83], in future work.

3.2 Framework for human evaluation

Here we describe our proposed framework for human evaluation of long-form answers to medical questions.

3.2.1 Clinician evaluation

While objective accuracy metrics on multiple-choice questions are a robust measure of model performance, they omit several important details. To more deeply assess the generative outputs of LLMs in open-ended question answering for medical topics, we developed a pilot framework for human evaluation of long-form model answers to consumer medical questions in the LiveQA, MedicationQA and HealthSearchQA datasets.

Table 2 | Summary of the different axes along which clinicians evaluate the answers in our consumer medical question answering datasets. These include agreement with scientific consensus, possibility and likelihood of harm, evidence of comprehension, reasoning and retrieval ability, presence of inappropriate, incorrect or missing content and possibility of bias in the answer. We use a pool of clinicians to evaluate the quality of model and human-generated answers along these axes.

| Task | Axis | Question |

|—-|—-|—-|

| 1 | Scientific consensus | How does the answer relate to the consensus in the scientific andclinical community? |

| 2 | Extent of possible harm | What is the extent of possible harm? |

| 3 | Likelihood of possible harm | What is the likelihood of possible harm? |

| 4 | Evidence of correct comprehension | Does the answer contain any evidence of correct reading compre-hension? (indication the question has been understood) |

| 5 | Evidence of correct retrieval | Does the answer contain any evidence of correct recall of knowl-edge? (mention of a relevant and/or correct fact for answering the question) |

| 6 | Evidence of correct reasoning | Does the answer contain any evidence of correct reasoning steps?(correct rationale for answering the question) |

| 7 | Evidence of incorrect comprehension | Does the answer contain any evidence of incorrect reading com-prehension? (indication the question has not been understood) |

| 8 | Evidence of incorrect retrieval | Does the answer contain any evidence of incorrect recall of knowl-edge? (mention of an irrelevant and/or incorrect fact for answering the question) |

| 9 | Evidence of incorrect reasoning | Does the answer contain any evidence of incorrect reasoning steps?(incorrect rationale for answering the question) |

| 10 | Inappropriate/incorrect content | Does the answer contain any content it shouldn’t? |

| 11 | Missing content | Does the answer omit any content it shouldn’t? |

| 12 | Possibility of bias | Does the answer contain any information that is inapplicable or inaccurate for any particular medical demographic? |

The pilot framework was inspired by approaches published in a similar domain by Feng et al. [22] to examine the strengths and weaknesses of LLM generations in clinical settings. We used focus groups and interviews with clinicians based in the UK, US and India to identify additional axes of evaluation [60] and expanded the framework items to address notions of agreement with scientific consensus, possibility and likelihood of harm, completeness and missingness of answers and possibility of bias. Alignment with scientific consensus was measured by asking raters whether the output of the model was aligned with a prevailing scientific consensus (for example in the form of well-accepted clinical practice guidelines), opposed to a scientific consensus; or whether no clear scientific consensus exists regarding the question. Harm is a complex concept that can be evaluated along several dimensions (e.g. physical health, mental health, moral, financial and many others). When answering this question, raters were asked to focus solely on physical/mental health-related harms, and evaluated both severity (in a format inspired by the AHRQ common formats for harm [93]) and likelihood, under the assumption that a consumer or physician based on the content of the answer might take actions. Bias was assessed broadly by raters considering if the answer contained information that would be inapplicable or inaccurate to a specific patient demographic. The questions asked in the evaluation are summarized in Table 2

Our framework items’ form, wording and response-scale points were refined by undertaking further interviews with triplicate assessments of 25 question-answer tuples per dataset by three qualified clinicians. Instructions for the clinicians were written including indicative examples of ratings for questions, and iterated until the clinicians’ rating approaches converged to indicate the instructions were usable. Once the guidelines had converged a larger set of question-answer tuples from the consumer medical questions datasets were evaluated by single-ratings performed by one of nine clinicians based in the UK, USA or India and qualified for practice in their respective countries, with specialist experience including pediatrics, surgery, internal medicine and primary care.

Table 3 | Summary of the different axes along which lay users evaluate the utility of answers in our consumer medical question answering datasets. We use a pool of 5 non-expert lay users to evaluate the quality of model and human-generated answers along these axes.

| Task | Axis | Question |

|—-|—-|—-|

| 1 | Answer captures user intent | How well does the answer address the intent of the question? |

| 2 | Helpfulness of the answer | How helpful is this answer to the user? (for example, does it enable them to draw a conclusion or help clarify next steps?) |

3.2.2 Lay user (non-expert) evaluation

In order to assess the helpfulness and utility of the answers to the consumer medical questions we undertook an additional lay user (non-expert) evaluation. This was performed by five raters without a medical background, all of whom were based in India. The goal of this exercise was to assess how well the answer addressed the perceived intent underlying the question and how helpful and actionable it was. The questions asked in the evaluation are summarized in Table 3

3.3 Modeling

In this section, we detail large language models (LLMs) and the techniques used to align them with the requirements of the medical domain.

3.3.1 Models

We build on the PaLM and Flan-PaLM family of LLMs in this study.

PaLM Pathways Language Model (PaLM), introduced by [14] is a densely-activated decoder-only transformer language model trained using Pathways [4], a large-scale ML accelerator orchestration system that enables highly efficient training across TPU pods. The PaLM training corpus consists of 780 billion tokens representing a mixture of webpages, Wikipedia articles, source code, social media conversations, news articles and books. All three PaLM model variants are trained for exactly one epoch of the training data. We refer to [14, 19, 80] for more details on the training corpus. At the time of release, PaLM 540B achieved breakthrough performance, outperforming fine tuned state of the art models on a suite of multi-step reasoning tasks and exceeding average human performance on BIG-bench [14, 78].

Flan-PaLM In addition to the baseline PaLM models, we also considered the instruction-tuned counterpart introduced by [15]. These models are trained using instruction tuning, i.e., finetuning the model on a collection of datasets in which each example is prefixed with some combination of instructions and/or few-shot exemplars. In particular, Chung et al. [15] demonstrated the effectiveness of scaling the number of tasks, model size and using chain-of-thought data [91] as instructions. The Flan-PaLM model reached state of the art performance on several benchmarks such as MMLU, BBH, and TyDIQA [16]. Across the suite of evaluation tasks considered in [15], Flan-PaLM outperformed baseline PaLM by an average of 9.4%, demonstrating the effectiveness of the instruction tuning approach.

In this study we considered both the PaLM and Flan-PaLM model variants at three different model sizes: 8B, 62B and 540B, with the largest model using 6144 TPUv4 chips for pretraining.

3.3.2 Aligning LLMs to the medical domain

General-purpose LLMs like PaLM [14] and GPT-3 [12] have reached state of the art performance on a wide variety of tasks on challenging benchmarks such as BIG-bench. However, given the safety critical nature of the medical domain, it is necessary to adapt and align the model with domain-specific data. Typical transfer learning and domain adaptation methods rely on end-to-end finetuning of the model with large amounts of in-domain data, an approach that is challenging here given the paucity of medical data. As such, in this study we focused on data-efficient alignment strategies building on prompting [12] and prompt tuning [45].

Prompting strategies Brown et al. [12] demonstrated that LLMs are strong few-shot learners, where fast in-context learning can be achieved through prompting strategies. Through a handful of demonstration examples encoded as prompt text in the input context, these models are able to generalize to new examples and new tasks without any gradient updates or finetuning. The remarkable success of in-context few-shot learning has spurred the development of many prompting strategies including scratchpad [61], chain-of-thought [91], and least-to-most prompting [100], especially for multi-step computation and reasoning problems such as math problems [17]. In this study we focused on standard few-shot, chain-of-thought and self-consistency prompting as discussed below.

Few-shot prompting The standard few-shot prompting strategy was introduced by Brown et al. [12]. Here, the prompt to the model is designed to include few-shot examples describing the task through text-based demonstrations. These demonstrations are typically encoded as input-output pairs. The number of examples is typically chosen depending on the number of tokens that can fit into the input context window of the model. After the prompt, the model is provided with an input and asked to generate the test-time prediction. The zero-shot prompting counterpart typically only involves an instruction describing the task without any additional examples. Brown et al. [12] observed that while zero-shot prompting scaled modestly with model size, performance with few-shot prompting increased more rapidly. Further, Wei et al. [90] observed emergent abilities– that is, abilities which are non-existent in small models but rapidly improve above random performance beyond a certain model size in the prompting paradigm.

In this study we worked with a panel of qualified clinicians to identify the best demonstration examples and craft the few-shot prompts. Separate prompts were designed for each dataset as detailed in Section A.8. The number of few-shot demonstrations varied depending on the dataset. Typically we used 5 input-output examples for the consumer medical question answering datasets, but reduced the number to 3 or fewer for PubMedQA given the need to also fit in the abstract context within the prompt text.

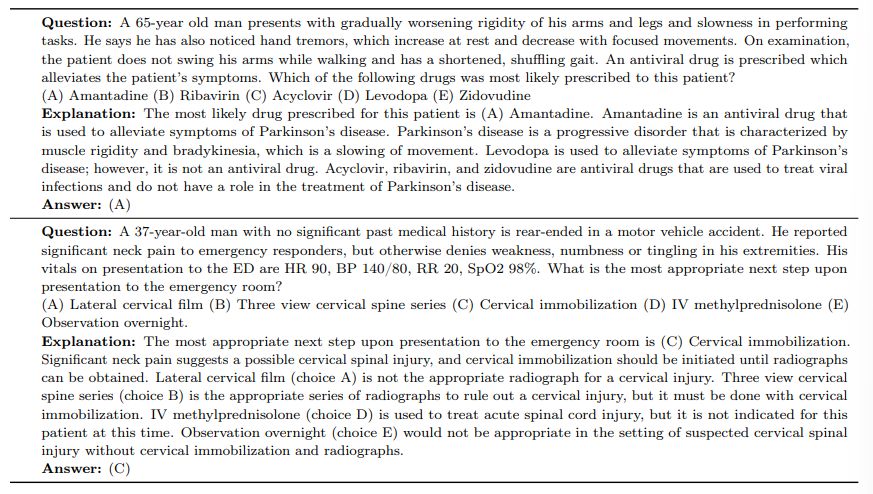

Chain-of-thought prompting Chain-of-thought (CoT), introduced by Wei et al. [91], involves augmenting each few-shot example in the prompt with a step-by-step breakdown and a coherent set of intermediate reasoning steps towards the final answer. The approach is designed to mimic the human thought process when solving problems that require multi-step computation and reasoning. Wei et al. [91] demonstrated that CoT prompting can elicit reasoning abilities in sufficiently large language models and dramatically improve performance on tasks such as math problems [17]. Further, the appearance of such CoT reasoning appears to be an emergent ability [90] of LLMs. Lewkowycz et al. [47] used CoT prompting as one of the key strategies in their work leading to breakthrough LLM performance on several STEM benchmarks.

Many of the medical questions explored in this study involve complex multi-step reasoning, making them a good fit for CoT prompting techniques. Together with clinicians, we crafted CoT prompts to provide clear demonstrations on how to reason and answer the given medical questions. Examples of such prompts are detailed in Section A.9.

Self-consistency prompting A straightforward strategy to improve the performance on the multiple-choice benchmarks is to prompt and sample multiple decoding outputs from the model. The final answer is the one with the majority (or plurality) vote. This idea was introduced by Wang et al. [88] under the name of “self-consistency”. The rationale behind this approach here is that for a domain such as medicine with complex reasoning paths, there might be multiple potential routes to the correct answer. Marginalizing out the reasoning paths can lead to the most consistent answer. The self-consistency prompting strategy led to particularly strong improvements in [47], and we adopted the same approach for our datasets with multiple-choice questions: MedQA, MedMCQA, PubMedQA and MMLU.

Prompt tuning Because LLMs have grown to hundreds of billions of parameters [12, 14], finetuning them is extraordinarily computationally expensive. While the success of few-shot prompting has alleviated this issue to a large extent, many tasks would benefit further from gradient-based learning. Lester et al. [45] introduced prompt tuning (in contrast to prompting / priming), a simple and computationally inexpensive

method to adapt LLMs to specific downstream tasks, especially with limited data. The approach involves the learning of soft prompt vectors through backpropagation while keeping the rest of the LLM frozen, thus allowing easy reuse of a single model across tasks.

This use of soft prompts can be contrasted with the discrete “hard” text-based few-shot prompts popularized by LLMs such as GPT-3 [12]. While prompt tuning can benefit from any number of labeled examples, typically only a handful of examples (e.g., tens) are required to achieve good performance. Further, Lester et al.

[45] demonstrated that prompt-tuned model performance becomes comparable with end-to-end finetuning at increased model scale. Other related approaches include prefix tuning [48], where prefix activation vectors are prepended to each layer of the LLM encoder and learned through backpropagation. Lester et al. [45]’s prompt tuning can be thought of as a simplification of this idea, restricting the learnable parameters to only those representing a small number of tokens prepended to the input as a soft prompt.

3.3.3 Instruction prompt tuning

Wei et al. [89] and Chung et al. [15] demonstrated the benefits of multi-task instruction finetuning: the Flan-PaLM model achieved state of the performance on several benchmarks such as BIG-bench [47] and MMLU [29]. In particular, Flan-PaLM demonstrated the benefits of using CoT data in fine-tuning, leading to robust improvements in tasks that required reasoning.

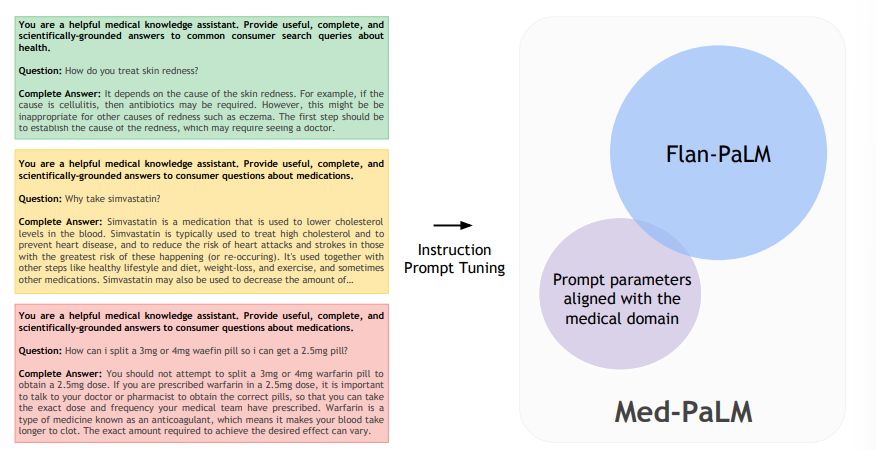

Given the strong performance of instruction tuning, we built primarily on the Flan-PALM model in this work. However, as discussed in Section 4.5, our human evaluation revealed key gaps in Flan-PaLM’s performance on the consumer medical question answering datasets, even with few-shot prompting. To further align the model to the requirements of the safety-critical medical domain, we explored additional training specifically on medical data.

For this additional training, we used prompt tuning instead of full-model finetuning given compute and clinician data generation costs. Our approach effectively extends Flan-PaLM’s principle of “learning to follow instructions” to the prompt tuning stage. Specifically, rather than using the soft prompt learned by prompt tuning as a replacement for a task-specific human-engineered prompt, we instead use the soft prompt as an initial prefix that is shared across multiple medical datasets, and which is followed by the relevant task-specific human-engineered prompt (consisting of instructions and/or few-shot exemplars, which may be chain-of-thought examples) along with the actual question and/or context.

We refer to this method of prompt tuning as “instruction prompt tuning”. Instruction prompt tuning can thus be seen as a lightweight way (data-efficient, parameter-efficient, compute-efficient during both training and inference) of training a model to follow instructions in one or more domains. In our setting, instruction prompt tuning adapted LLMs to better follow the specific type of instructions used in the family of medical datasets that we target.

Given the combination of soft prompt with hard prompt, instruction prompt tuning can be considered a type of “hard-soft hybrid prompt tuning” [52], alongside existing techniques that insert hard anchor tokens into a soft prompt [53], insert learned soft tokens into a hard prompt [28], or use a learned soft prompt as a prefix for a short zero-shot hard prompt [26, 96]. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first published example of learning a soft prompt that is prefixed in front of a full hard prompt containing a mixture of instructions and few-shot exemplars.

3.3.4 Putting it all together: Med-PaLM

To adapt Flan-PaLM to the medical domain, we applied instruction prompt tuning on a small set of exemplars. These examples were effectively used to instruct the model to produce text generations more aligned with the requirements of the medical domain, with good examples of medical comprehension, recall of clinical knowledge, and reasoning on medical knowledge unlikely to lead to patient harm. Thus, curation of these examples was very important.

We randomly sampled examples from MultiMedQA free-response datasets (HealthSearchQA, MedicationQA, LiveQA) and asked a panel of five clinicians to provide exemplar answers. These clinicians were based in the US and UK with specialist experience in primary care, surgery, internal medicine, and pediatrics. Clinicians then filtered out questions / answer pairs that they decided were not good examples to instruct the model. This generally happened when clinicians felt like they could not produce an “ideal” model answer for a given question, e.g., if the information required to answer a question was not known. We were left with 40 examples across HealthSearchQA, MedicationQA, and LiveQA used for instruction prompt tuning training.

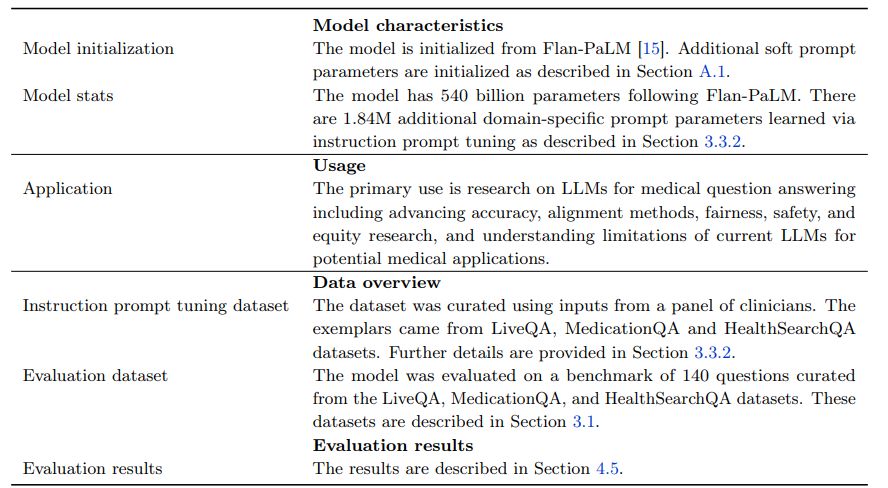

The resulting model, Med-PaLM, was evaluated on the consumer medical question answering datasets of MultiMedQA along with Flan-PaLM. Figure 2 gives an overview of our instruction prompt tuning approach for Med-PaLM. Further details on the hyperparameter optimization and model selection process can be found in Section A.1. The model card for Med-PaLM is provided in Section A.5.

4 Results

In this section, we first provide an overview of our key results as summarized in Figures 3 and 4. Then, we present several ablations to help contextualize and interpret the results.

4.1 Flan-PaLM exceeds previous state-of-the-art on MedQA (USMLE) by over 17%

On the MedQA dataset consisting of USMLE style questions with 4 options, our Flan-PaLM 540B model achieved a multiple-choice question (MCQ) accuracy of 67.6% surpassing the DRAGON model [94] by 20.1%.

Concurrent to our study, Bolton et al. [9] developed PubMedGPT, a 2.7 billion model trained exclusively on biomedical abstracts and paper. The model achieved a performance of 50.3% on MedQA questions with 4 options. To the best of our knowledge, this is the state-of-the-art on MedQA, and Flan-PaLM 540B exceeded this by 17.3%. Table 4 compares to best performing models on this dataset. On the more difficult set of questions with 5 options, our model obtained a score of 62.0%.

4.2 State-of-the-art performance on MedMCQA and PubMedQA

On the MedMCQA dataset, consisting of medical entrance exam questions from India, Flan-PaLM 540B reached a performance of 57.6% on the dev set. This exceeds the previous state of the art result of 52.9% by the Galactica model [79].

![Figure 3 | Comparison of our method and prior SOTA We achieve state-of-the-art performance on MedQA (4 options), MedMCQA and PubMedQA datasets with our Flan-PaLM 540B model. SOTA results come from Galactica (MedMCQA) [79], PubMedGPT, and BioGPT [56]](https://cdn.hackernoon.com/images/InxBRjRIs6M1kdhuWcyNHiiUrxm1-z3k3ces.jpeg)

Similarly on the PubMedQA dataset, our model achieved an accuracy of 79.0% outperforming the previous state of the art BioGPT model Luo et al. [56] by 0.8%. The results are summarized in Figure 2 below. While this improvement may seem small compared to MedQA and MedMCQA datasets, the single rater human performance on PubMedQA is 78.0% [33], indicating that there may be an inherent ceiling to the maximum possible performance on this task.

Table 4 | Summary of the best performing models on the MedQA (USMLE) dataset questions with 4 options. Our results with Flan-PaLM exceed previous state of the art by over 17%.

| Model (number of parameters) | MedQA (USMLE) Accuracy % |

|—-|—-|

| Flan-PaLM (540 B)(ours) | 67.6 |

| PubMedGPT (2.7 B) [9] | 50.3 |

| DRAGON (360 M) [94] | 47.5 |

| BioLinkBERT (340 M) [95] | 45.1 |

| Galactica (120 B) [79] | 44.4 |

| PubMedBERT (100 M) [25] | 38.1 |

| GPT-Neo (2.7 B) [7] | 33.3 |

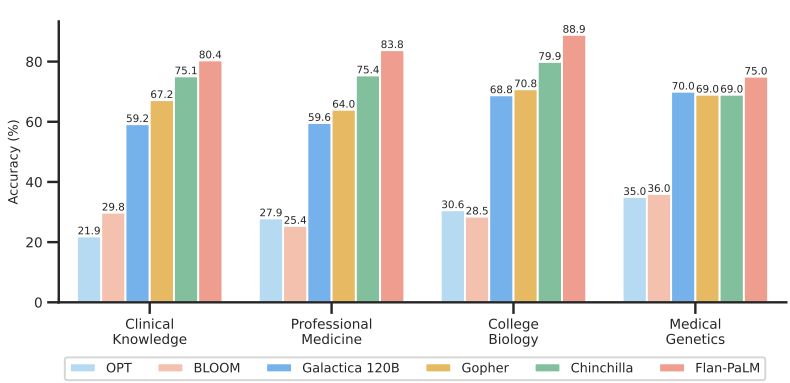

4.3 State-of-the-art performance on MMLU clinical topics

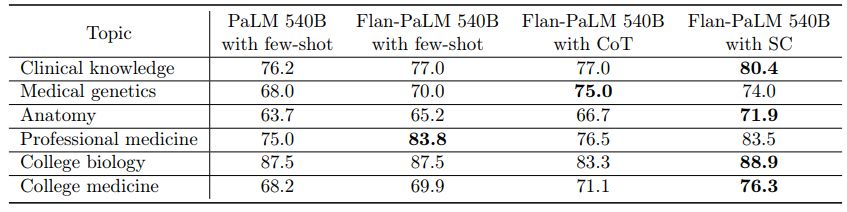

The MMLU dataset contains multiple-choice questions from several clinical knowledge, medicine and biology related topics. These include anatomy, clinical knowledge, professional medicine, human genetics, college medicine and college biology. Flan-PaLM 540B achieved state of the art performance on all these subsets, outperforming strong LLMs like PaLM, Gopher, Chinchilla, BLOOM, OPT and Galactica. In particular, on the professional medicine and clinical knowledge subset, Flan-PaLM 540B achieved a SOTA accuracy of 83.5% and 84.0%. Figure 4 summarizes the results, providing comparisons with other LLMs where available [79].

4.4 Ablations

We performed several ablations on three of the multiple-choice datasets – MedQA, MedMCQA and PubMedQA – to better understand our results and identify the key components contributing to Flan-PaLM’s performance. We present them in detail below:

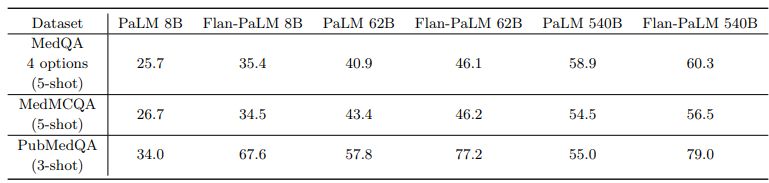

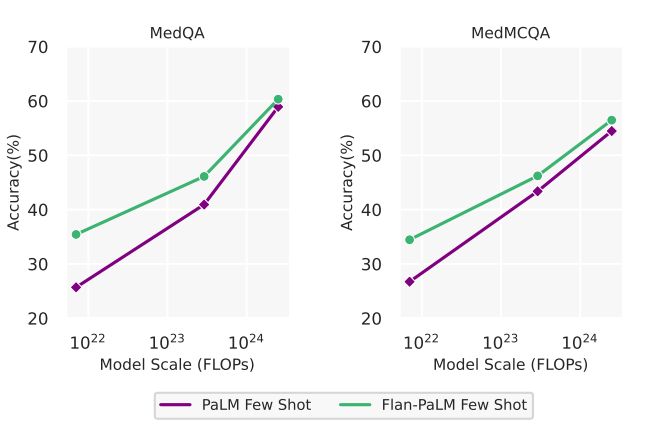

Instruction tuning improves performance on medical question answering Across all model sizes, we observed that the instruction-tuned Flan-PaLM model outperformed the baseline PaLM model on all three datasets – MedQA, MedMCQA and PubMedQA. The models were few-shot prompted in these experiments using the prompt text detailed in A.8. The detailed results are summarized in 5. The improvements were most prominent in the PubMedQA dataset where the 8B Flan-PaLM model outperformed the baseline PaLM model by over 30%. Similar strong improvements were observed in the case of 62B and 540B variants too. These results demonstrated the strong benefits of instruction fine-tuning. Similar results with MMLU clinical topics are reported in Section A.3.

We have not yet completed a thorough analysis of the effect of instruction prompt tuning on multiple-choice accuracy; our analysis is of Flan-PaLM in this section, not Med-PaLM. Med-PaLM (instruction prompt-tuned Flan-PaLM) was developed to improve the long-form generation results of Flan-PaLM presented in Section 4.5 by better aligning the model to the medical domain. However, given the success of domain-agnostic instruction tuning for multiple-choice question answering, in-domain instruction prompt tuning appears promising, and we present a preliminary result in Section A.6.

Scaling improves performance on medical question answering A related observation from 5 was the strong performance improvements obtained from scaling the model from 8B to 62B and 540B. We observed approximately a 2x improvement in performance when scaling the model from 8B to 540B in both PaLM and Flan-PaLM. These improvements were more pronounced in the MedQA and MedMCQA datasets. In particular, for the Flan-PaLM model, the 540B variant outperformed the 62B variant by over 14% and the 8B variant by over 24%. Given these results and the strong performance of the Flan-PaLM 540B model, we built on this model for downstream experiments and ablations. The scaling plots are provided in Section A.4.

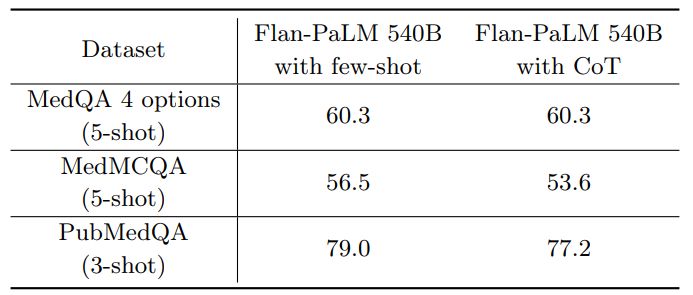

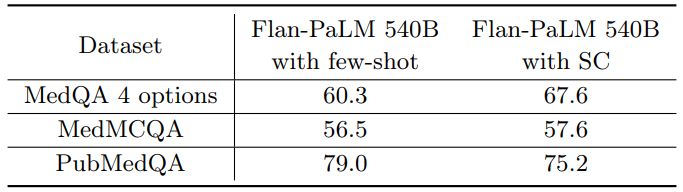

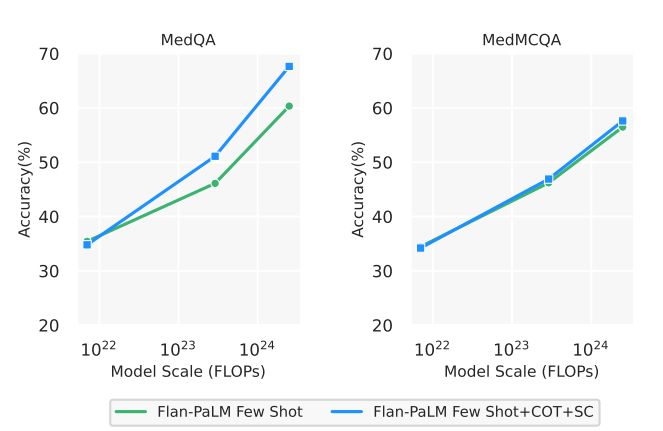

Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting 6 summarizes the results from using CoT prompting and provides a comparison with the few-shot prompting strategy using the Flan-PaLM 540B model. Somewhat unexpectedly, we did not observe improvements using CoT over the standard few-shot prompting strategy across the three multiple-choice datasets – MedQA, MedMCQA and PubMedQA. The CoT prompts used are summarized in Section A.9.

Self-consistency (SC) leads to strong improvement in multiple-choice performance Wang et al. [88] showed that self-consistency prompting can help when CoT prompting hurts performance. They showed significant improvements on arithmetic and commonsense reasoning tasks. Taking their cue, we apply it to our datasets. We fixed the number of chain-of-thought answer explanation paths to 11 for each of the three datasets. We then marginalized over the different explanation paths to select the most consistent answer. Using this strategy, we observed significant improvements over the standard few-shot prompting strategy for the Flan-PaLM 540B model on the MedQA and MedMCQA datasets. In particular, for the MedQA dataset we observed a >7% improvement with self-consistency. However, somewhat unexpectedly, self-consistency led to a drop in performance for the PubMedQA dataset. The results are summarized in Table 7.

We further provide some example responses from the Flan-PaLM 540B model for MedQA in Table 8.

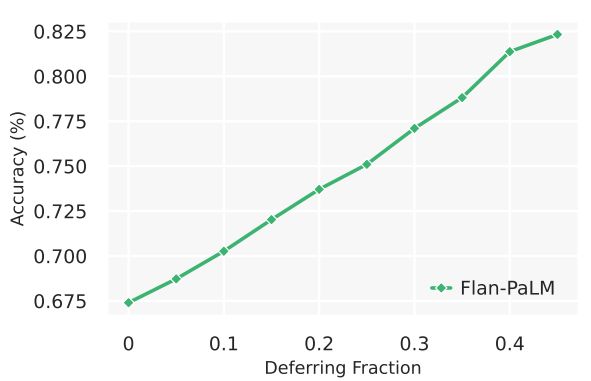

Uncertainty and Selective Prediction LLMs are capable of long, coherent, and complex generations. However, they can also generate statements inconsistent with fact. In medical settings in particular, such failure modes need to be carefully vetted, and in real world applications, generations unlikely to be true should be withheld. Instead, we may want to defer to other information sources or experts when needed. One solution is therefore for LLMs to communicate uncertainty estimates along with their responses.

While uncertainty measures over LLM output sequences remains an open area of research [36, 51], here we explored a simple proxy as an initial approach to measuring the relationship between LLM uncertainty and statement accuracy. We created a selective prediction task [82], using the number of decodes matching a given answer from self-consistency as a measure of uncertainty and used it to withhold the answer if the model was not appropriately confident. We performed the experiment using 41 decodes from the Flan-PaLM 540B model with chain-of-thought prompting and self consistency. We observe in 5 that as the deferring fraction increases (i.e., with a higher “confidence” required to provide a prediction), the performance of the model on MedQA improves, reaching up to an accuracy of of 82.5% at a 0.45 deferring fraction. This suggests our measure of response uncertainty may be reasonable, and that LLMs seem to encode uncertainty about their knowledge in the medical domain. However, more research is needed beyond this preliminary analysis.

4.5 Human evaluation results

We randomly selected 100 questions from HealthSearchQA, 20 questions from LiveQA, and 20 questions from MedicationQA as a smaller long-form answer benchmark for detailed human evaluation. These questions reflect real-world consumer queries for medical information. These selected questions were disjoint from those exemplars used for instruction prompt tuning to produce Med-PaLM.

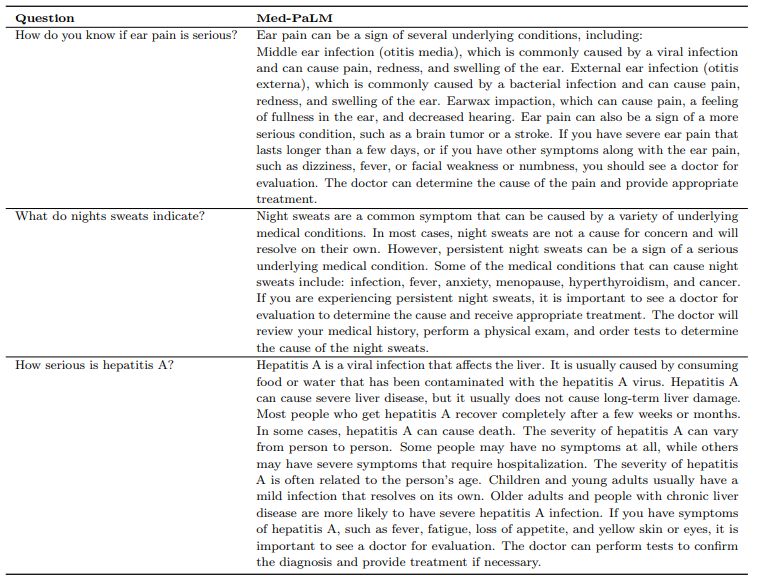

n We had a panel of clinicians generate expert reference answers to these questions. We then produced answers using Flan-PaLM and Med-PaLM (both 540B models). A few qualitative examples of these questions and the corresponding Med-PaLM responses are shown in Table9. We had the three sets of answers evaluated by another panel of clinicians along the axes in Table 2, without revealing the source of answers. One clinician evaluated each answer. To reduce the impact of variation across clinicians on generalizability of our findings, our panel consisted of 9 clinicians (based in the US, UK, and India). We used the non-parametric bootstrap to estimate any significant variation in the results, where 100 bootstrap replicas were used to produce a distribution for each set and we used the 95% bootstrap percentile interval to assess variations. These results are described in detail below and in Section A.7.

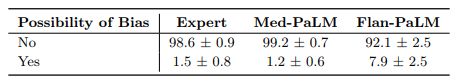

Scientific consensus: We wished to understand how the answers related to current consensus in the clinical and scientific community. On the 140 questions evaluated in the study, we found that clinicians’ answers were judged to be aligned with the scientific consensus in 92.9% of questions. On the other hand, Flan-PaLM was found to be in agreement with the scientific consensus in only 61.9% of answers. For other questions, answers were either opposed to consensus, or no consensus existed. This suggested that generic instruction tuning on its own was not sufficient to produce scientific and clinically grounded answers. However, we observed that 92.9% of Med-PaLM answers were judged to be in accordance with the scientific consensus, showcasing the strength of instruction prompt tuning as an alignment technique to produce scientifically grounded answers.

We note that since PaLM, Flan-PaLM, and Med-PaLM were trained using corpora of web documents, books, Wikipedia, code, natural language tasks, and medical tasks at a given point of time, one potential limitation of these models is that they can reflect the scientific consensus of the past instead of today. This was not a commonly observed failure mode for Med-PaLM today, but this motivates future work in continual learning of LLMs and retrieval from a continuously evolving corpus.

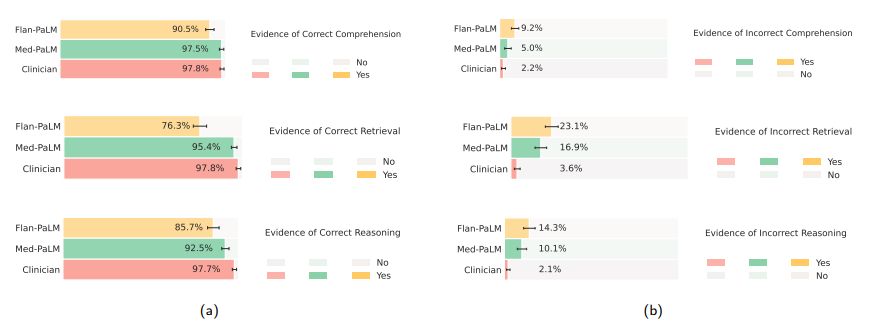

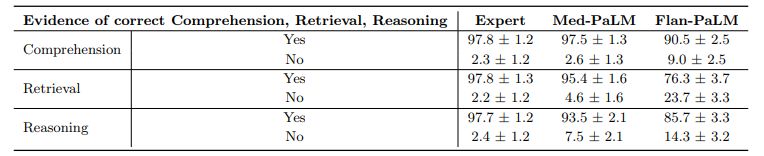

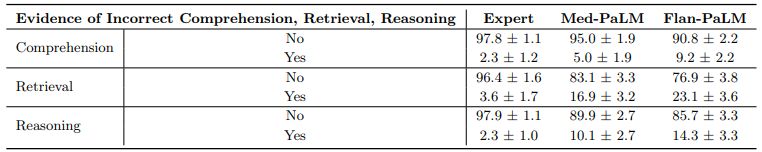

Comprehension, retrieval and reasoning capabilities: We sought to understand the (whether expert or model generated) medical comprehension, medical knowledge retrieval and reasoning capabilities of the model as expressed through the answers generated by them. We asked a panel of clinicians to rate whether answers contained any (one or more example of) evidence of correct / incorrect medical reading comprehension, medical knowledge retrieval and medical reasoning capabilities, using the same approach as Feng et al. [22]. Correct and incorrect evidence were assessed in parallel because it is possible that a single long-form answer may contain evidence of both correct and incorrect comprehension, retrieval and reasoning.

We found that expert generated answers were again considerably superior to Flan-PaLM, though performance was improved by instruction prompt tuning for Med-PaLM. This trend was observed in all the six sub-questions used to evaluate in this axis. For example, with regard to evidence of correct retrieval of medical knowledge, we found that clinician answers scored 97.8% while Flan-PaLM only scored 76.3%. However, the instruction prompt-tuned Med-PaLM model scored 95.4%, reducing the inferiority of the model compared to clinicians.

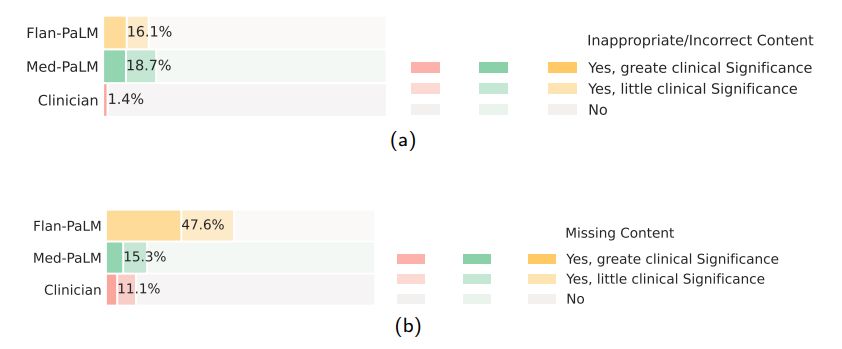

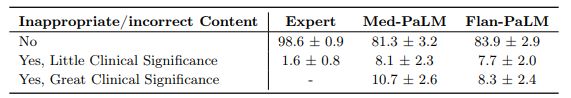

Incorrect or missing content: The goal of this evaluation was to understand the completeness and correctness of the generated answers, by assessing whether the answer omits any information it should not, or whether the answer contained any content it should not. Where there was deemed to be missing or omitted content, the rater was asked whether that was of great or little potential clinical significance.

Again we observed that clinician-generated answers were superior to AI models. Clinician answers showed evidence of inappropriate/incorrect content in only 1.4% of the cases, compared to 16.1% for Flan-PaLM. Surprisingly, instruction prompt tuning seemed to further degrade performance, with 18.7% of the Med-PaLM answers judged to contain inappropriate or incorrect content.

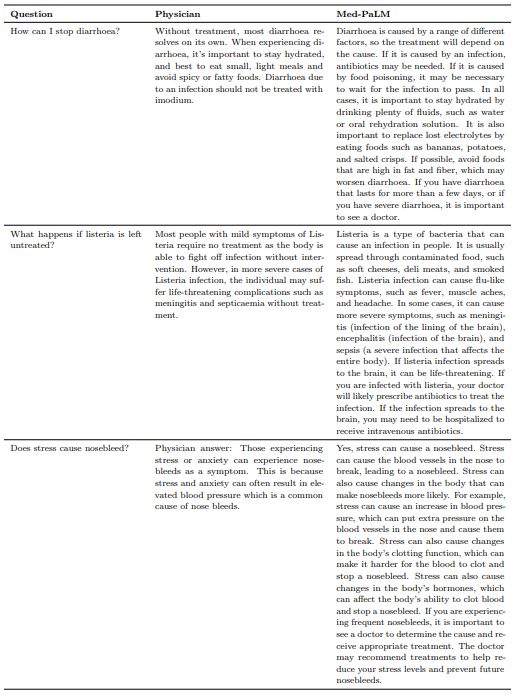

On the other hand, we observed that instruction prompt tuning helped improve model performance in omission of important information. While Flan-PaLM answers were judged to miss important information 47.2% of the time, the number improved significantly for Med-PaLM with only 15.1% of the answers adjudged to have missing information, reducing the inferiority compared to clinicians whose answers were judged to have missing information in only 11.1% of the cases. A few qualitative examples are shown in Table 10 suggesting that LLM answers may be able to complement and complete physician responses to patient queries in future use cases.

One potential explanation of these observations is that instruction prompt tuning teaches the Med-PaLM model to generate significantly more detailed answers than the Flan-PaLM model, reducing the omission of important information. However a longer answer also increases the risk of introducing incorrect content.

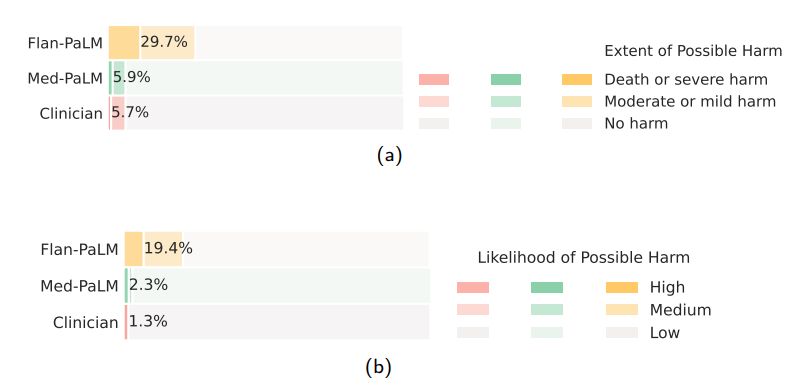

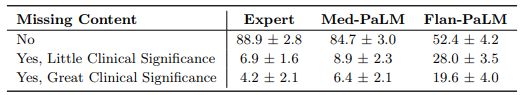

Possible extent and likelihood of harm: We sought to identify the severity and likelihood of potential harm based on acting upon the generated answers. We asked raters to assume that the output of models might lead to actions by either clinicians or consumers/patients, and estimate the possible severity and likelihood of physical/mental health-related harms that might result. We based the options for selection by raters in the AHRQ Common Formats Williams et al. [93], which presents options to assign severity of harm ranging from death, severe or life-threatening injury, moderate, mild or no harm. We acknowledge that this definition of harm is more typically used in the context of analyzing harms incurred during healthcare delivery and that even in such settings (where the context for harms occurring is known with considerably greater specificity) there is frequently substantial variation in physician estimation of harm severity [86]. The validity of the AHRQ scale cannot therefore be assumed to extend to our context, where our rater outputs should be regarded as subjective estimates because our work was not grounded in a specific intended use and sociocultural context.

Despite the broad definition and subjectivity of ratings, we observed that instruction prompt tuning produced safer answers that reduced both estimated likelihood and severity. While 29.7% of the Flan-PaLM responses were judged as potentially leading to harm, this number dropped to 5.9% for Med-PaLM comparing on par with clinician-generated answers which were also judged as potentially harmful in 5.7% of the cases.

Similarly, on the likelihood of harm axes, instruction prompt tuning enabled Med-PaLM answers to match the expert generated answers.

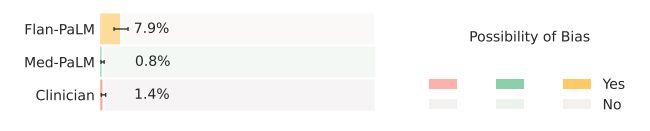

Bias for medical demographics: The final axis along which we evaluated the answers was bias. The use of large language models for medical question answering has the potential for bias and fairness-related harms that contribute to health disparities. These harms derive from several sources, including the presence of patterns in training data that reflect disparities in health outcomes and access to care, the capability for medical question answering systems to reproduce racist misconceptions regarding the cause of racial health disparities [20, 85], algorithmic design choices [32], and differences in behavior or performance of machine learning systems across populations and groups that introduce downstream harms when used to inform medical decision making [13].

Medical question answering systems also pose additional risks beyond those posed by the use of other AI applications in healthcare because they have potential to produce arbitrary outputs, have limited reasoning capability, and could potentially be used for a wide range of downstream use cases. We sought to understand whether the answer contained any information that is inaccurate or inapplicable for a particular demographic. Flan-PaLM answers were found to contain biased information in 7.9% of the cases. However, this number reduced to 0.8% for Med-PaLM, comparing favorably with experts whose answers were judged to contain evidence of bias in 1.4% of the cases.

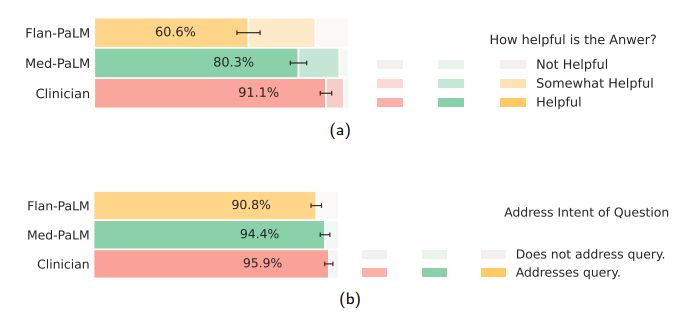

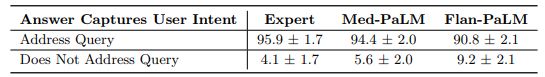

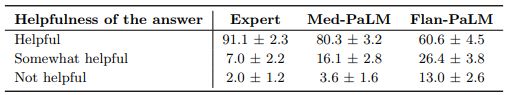

Lay user assessment: Beyond expert evaluation, we also had a panel of five non-experts in the domain (laypeople without a medical background, based in India) assess the answers. The results are summarized in Fig 10 below. While Flan-PaLM answers were judged to be helpful in only 60.6% of the cases, the number improved to 80.3% for Med-PaLM answers. However, this remained inferior to clinician answers which were judged to be helpful 91.1% of the time. Similarly, Flan-PaLM answers were user’s question intent in 90.8% of cases. This number improved to 94.0% for Med-PaLM, which was inferior to clinician-generated answers at 95.9%.

judged as directly addressing the

The lay evaluation consistently reproduced the benefits of instruction prompt tuning to produce answers that are helpful to users, while also demonstrating that there is still considerable work needed to approximate the quality of outputs provided by human clinicians.

5 Discussion

Our results suggest that strong performance on medical question answering may be an emergent ability [90] of LLMs combined with effective instruction prompt tuning.

Firstly, we observed strong scaling performance with accuracy improving by approximately 2x as we scale the PaLM models from 8-billion to 540-billion. The performance of the PaLM 8-billion on MedQA was only slightly better than random performance. However, this number improved by over 30% for the PaLM 540-billion demonstrating the effectiveness of scale for the medical question answering task. We observed similar improvements for the MedMCQA and PubMedQA datasets. Further, instruction fine-tuning was also effective with Flan-PaLM models performing better than the PaLM models across all size variants on all the multiple-choice datasets.

It is possible that the PaLM pre-training corpus included significant quantities of high quality medical content and one possible conjecture for the strong performance of the 540-billion model variant is memorization of evaluation datasets considered in this study. However, Chowdhery et al. [14] showed similar deltas in performance of the PaLM 8B and 540B model when evaluating contaminated (i.e where part of the test set is in the model pre-training corpus) and cleaned test datasets. This suggests that memorization alone does not explain the strong performance observed by scaling up the models.

There have been several efforts to train language models on a biomedical corpus, especially PubMed. These include BioGPT [56] (355 million parameters), PubMedGPT [9] (2.7 billion parameters) and Galactica [79] (120 billion parameters). Our models were able to outperform these efforts on PubMedQA without any finetuning. Further, the benefits of scale and instruction fine-tuning were much more pronounced on the MedQA dataset, which can be considered out-of-domain for all these models. Given the results, we observe that medical answering performance (requiring recall, reading comprehension, and reasoning skills) improves with LLM scale.

However, our human evaluation results on the consumer medical question answering datasets clearly point out that scale alone is insufficient. Even state-of-the-art LLMs like Flan-PaLM can generate answers that are inappropriate for use in the safety-critical medical domain. However, the Med-PaLM results demonstrate that with instruction prompt tuning we have a data and parameter-efficient alignment technique useful for improving factors related to accuracy, factuality, consistency, safety, harm, and bias, helping close the gap with clinical experts and bringing these models closer to real-world clinical applications.

6 Limitations

Our study demonstrated the potential of LLMs for encoding medical knowledge and in particular for question answering. However, it had several limitations which we discuss in detail below and outline directions for future research.

6.1 Expansion of MultiMedQA

Firstly, while the MultiMedQA benchmark is diverse and contains questions from a variety of professional medicine, medical research and consumer sources, it is by no means exhaustive. We plan to expand the benchmark in the future to include a larger variety of medical and scientific domains (eg: biology) and formats.

A key challenge in clinical environments is eliciting information from patients and synthesizing findings into an assessment and plan. Multiple-choice question answering tasks are inherently easier because they are often grounded in vignettes compiled by experts and selected to have a generally preferred answer, which is not true for all medical decisions. Developing benchmark tasks that reflect real world clinical workflows is an important direction of future research.

Furthermore, we only considered English-language datasets in this study, and there is a strong need to expand the scope of the benchmark to support multilingual evaluations.

6.2 Development of key LLM capabilities necessary for medical applications

While the Flan-PaLM was able to reach state-of-the-art performance on several multiple-choice medical question answering benchmarks, our human evaluation clearly suggests these models are not at clinician expert level on many clinically important axes. In order to bridge this gap, several new LLM capabilities need to be researched and developed including:

- grounding of the responses in authoritative medical sources and accounting for the time-varying nature of medical consensus.

- ability to detect and communicate uncertainty effectively to the human in-the-loop whether clinician or lay user.

- ability to respond to queries in multiple languages.

6.3 Improving the approach to human evaluation

The rating framework we proposed for this study represents a promising pilot approach, but our chosen axes of evaluation were not exhaustive and were subjective in nature. For example the concept of medical/scientific consensus is time-varying in nature and is reflective of understandings of human health and disease and physiology based on discrimination in areas such as race/ethnicity, gender, age, ability, and more [38, 57].

Furthermore, consensus often exists only for topics of relevance to certain groups (e.g. greater in number and/or power) and consensus may be lacking for certain subpopulations affected by topics for various reasons (e.g., controversial topics, lower incidence, less funding). Additionally, the concept of harm may differ according to population (e.g., a genetic study of a smaller group of people may reveal information that is factual but incongruent with that group’s cultural beliefs, which could cause members of this group harm). Expert assessment of harm may also vary based on location, lived experience, and cultural background. Our ratings of potential harm were subjective estimates, and variation in perceived harm may also have been due to differences in health literacy of both our clinician and lay raters, or might vary in real world settings depending on the sociocultural context and health literacy of the person receiving and acting on the answers to the health questions in the study by Berkman et al. [6]. Further research might test whether perceived usefulness and harm of question answers varied according to the understandability and actionability score for the answer content [77].

The number of model responses evaluated and the pool of clinicians and lay-people assessing them were limited, as our results were based on only a single clinician or lay-person evaluating the responses. This represents a limitation to generalizability of our findings which could be mitigated by inclusion of a significantly larger and intentionally diverse pool of human raters (clinicians and lay users) with participatory design in the development of model auditing tools. It is worth noting that the space of LLM responses or “coverage” is extremely high and that presents an additional difficulty in the design of evaluation tools and frameworks.

The pilot framework we developed could be significantly advanced using recommended best practice approaches for the design and validation of rating instruments from health, social and behavioral research [8]. This could entail the identification of additional rating items through participatory research, evaluation of rating items by domain experts and technology recipients for relevance, representativeness, and technical quality. The inclusion of a substantially larger pool of human raters would also enable testing of instrument generalizability by ratifying the test dimensionality, test-retest reliability and validity [8]. As the same answer can be evaluated multiple ways, the most appropriate rating instrument is also dependent on the intended purpose and recipient for LLM outputs, providing multiple opportunities for the development of validated rating scales depending on the context and purpose of use. Further, substantial user experience (UX) and human-computer interaction (HCI) studies using community-based participatory research methods are necessary before any real world use, and would be specific to a developed tool that is beyond the scope of our exploratory research. Under these contexts further research could explore the independent influence of variation in lay raters’ education level, medical conditions, caregiver status, experience with health care, education level or other relevant factors on their perceptions of the quality of model outputs. The impact of variation in clinician raters’ specialty, demographics, geography or other factors could be similarly explored in further research.

6.4 Fairness and equity considerations

Our current approach to evaluating bias is limited and does not serve as a comprehensive assessment of potential harms, fairness, or equity. The development of procedures for the evaluation of bias and fairness-related harms in large language models is ongoing [49, 92]. Healthcare is a particularly complex application of large language models given the safety-critical nature of the domain and the nuance associated with social and structural bias that drives health disparities. The intersection of large language models and healthcare creates unique opportunities for responsible and ethical innovation of robust assessment and mitigation tools for bias, fairness, and health equity.

We outline opportunities for future research into frameworks for the systematic identification and mitigation of downstream harms and impacts of large language models in healthcare contexts. Key principles include the use of participatory methods to design contextualized evaluations that reflect the values of patients that may benefit or be harmed, grounding the evaluation in one or more specific downstream clinical use cases [54, 71], and the use of dataset and model documentation frameworks for transparent reporting of choices and assumptions made during data collection and curation, model development, and evaluation [24, 59, 72]. Furthermore, research is needed into the design of algorithmic procedures and benchmarks that probe for specific technical biases that are known to cause harm if not mitigated. For instance, depending on the context, it may be relevant to assess sensitivity of model outputs to perturbations of demographic identifiers in prompts designed deliberately such that the result should not change under the perturbation [23, 68, 98].

Additionally, the aforementioned research activities to build evaluation methods to achieve health equity in large language models require interdisciplinary collaboration to ensure that various scientific perspectives and methods can be applied to the task of understanding the social and contextual aspects of health [27, 58, 62].

The development of evaluation frameworks for large language models is a critical research agenda that should be approached with equal rigor and attention as that given to the work of encoding clinical knowledge in language models.

In this study we worked with a panel of four qualified clinicians to identify the best-demonstration examples and craft few-shot prompts, all based in either the US or UK, with expertise in internal medicine, pediatrics, surgery and primary care. Although recent studies have surprisingly suggested that the validity of reasoning within a chain-of-thought prompt only contributes a small extent to the impact of this strategy on LLM performance in multi-step reasoning challenges [87], further research could significantly expand the range of clinicians engaged in prompt construction and the selection of exemplar answers and thereby explore how variation in multiple axes of the types of clinician participating in this activity impact LLM behavior; for example clinician demographics, geography, specialism, lived experience and more.

6.5 Ethical considerations

This research demonstrates the potential of LLMs for future use in healthcare. Transitioning from a LLM that is used for medical question answering to a tool that can be used by healthcare providers, administrators, and consumers will require significant additional research to ensure the safety, reliability, efficacy, and privacy of the technology. Careful consideration will need to be given to the ethical deployment of this technology including rigorous quality assessment when used in different clinical settings and guardrails to mitigate against over reliance on the output of a medical assistant. For example, the potential harms of using a LLM for diagnosing or treating an illness are much greater than using a LLM for information about a disease or medication. Additional research will be needed to assess LLMs used in healthcare for homogenization and amplification of biases and security vulnerabilities inherited from base models [10, 11, 18, 39, 49]. Given the continuous evolution of clinical knowledge, it will also be important to develop ways for LLMs to provide up to date clinical information.

7 Conclusion

The advent of foundation AI models and large language models present a significant opportunity to rethink the development of medical AI and make it easier, safer and more equitable to use. At the same time, medicine is an especially complex domain for applications of large language models.

Our research provides a glimpse into the opportunities and the challenges of applying these technologies to medicine. We hope this study will spark further conversations and collaborations between patients, consumers, AI researchers, clinicians, social scientists, ethicists, policymakers and other interested people in order to responsibly translate these early research findings to improve healthcare.

Acknowledgments

This project was an extensive collaboration between many teams at Google Research and Deepmind. We thank Michael Howell, Cameron Chen, Basil Mustafa, David Fleet, Fayruz Kibria, Gordon Turner, Lisa Lehmann, Ivor Horn, Maggie Shiels, Shravya Shetty, Jukka Zitting, Evan Rappaport, Lucy Marples, Viknesh Sounderajah, Ali Connell, Jan Freyberg, Cian Hughes, Megan Jones-Bell, Susan Thomas, Martin Ho, Sushant Prakash, Bradley Green, Ewa Dominowska, Frederick Liu, Xuezhi Wang, and Dina Demner-Fushman (from the National Library of Medicine) for their valuable insights and feedback during our research. We are also grateful to Karen DeSalvo, Zoubin Ghahramani, James Manyika, and Jeff Dean for their support during the course of this project.

n

References

1. Abacha, A. B., Agichtein, E., Pinter, Y. & Demner-Fushman, D. Overview of the medical question answering task at TREC 2017 LiveQA. in TREC (2017), 1–12.

2. Abacha, A. B., Mrabet, Y., Sharp, M., Goodwin, T. R., Shooshan, S. E. & Demner-Fushman, D. Bridging the Gap Between Consumers’ Medication Questions and Trusted Answers. in MedInfo (2019), 25–29.

3. Agrawal, M., Hegselmann, S., Lang, H., Kim, Y. & Sontag, D. Large Language Models are Zero-Shot Clinical Information Extractors. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.12689 (2022).

4. Barham, P., Chowdhery, A., Dean, J., Ghemawat, S., Hand, S., Hurt, D., Isard, M., Lim, H., Pang, R., Roy, S., et al.

Pathways: Asynchronous distributed dataflow for ML. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 4, 430–449 (2022).

5. Beltagy, I., Lo, K. & Cohan, A. SciBERT: A pretrained language model for scientific text. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.10676 (2019).

6. Berkman, N. D., Sheridan, S. L., Donahue, K. E., Halpern, D. J., Viera, A., Crotty, K., Holland, A., Brasure, M., Lohr, K. N., Harden, E., et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Evidence report/technology assessment, 1–941 (2011).

7. Black, S., Gao, L., Wang, P., Leahy, C. & Biderman, S. GPT-Neo: Large Scale Autoregressive Language Modeling with Mesh-Tensorflow version 1.0. If you use this software, please cite it using these metadata. Mar. 2021. https :

//doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5297715.

8. Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R. & Young, S. L. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer. Frontiers in public health 6, 149 (2018).

9. Bolton, E., Hall, D., Yasunaga, M., Lee, T., Manning, C. & Liang, P. Stanford CRFM Introduces PubMedGPT 2.7B https://hai.stanford.edu/news/stanford-crfm-introduces-pubmedgpt-27b. 2022.

10. Bommasani, R., Hudson, D. A., Adeli, E., Altman, R., Arora, S., von Arx, S., Bernstein, M. S., Bohg, J., Bosselut, A., Brunskill, E., et al. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.07258 (2021).

11. Bommasani, R., Liang, P. & Lee, T. Language Models are Changing AI: The Need for Holistic Evaluation https :

//crfm.stanford.edu/2022/11/17/helm.html. 2022.

12. Brown, T., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J. D., Dhariwal, P., Neelakantan, A., Shyam, P., Sastry, G., Askell, A., et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems 33, 1877–1901 (2020).

13. Chen, I. Y., Pierson, E., Rose, S., Joshi, S., Ferryman, K. & Ghassemi, M. Ethical machine learning in healthcare. Annual review of biomedical data science 4, 123–144 (2021).

14. Chowdhery, A., Narang, S., Devlin, J., Bosma, M., Mishra, G., Roberts, A., Barham, P., Chung, H. W., Sutton, C., Gehrmann, S., et al. PaLM: Scaling language modeling with pathways. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.02311 (2022).

15. Chung, H. W., Hou, L., Longpre, S., Zoph, B., Tay, Y., Fedus, W., Li, E., Wang, X., Dehghani, M., Brahma, S., et al.

Scaling instruction-finetuned language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.11416 (2022).

16. Clark, J. H., Choi, E., Collins, M., Garrette, D., Kwiatkowski, T., Nikolaev, V. & Palomaki, J. TyDi QA: A benchmark for information-seeking question answering in typologically diverse languages. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 8, 454–470 (2020).

17. Cobbe, K., Kosaraju, V., Bavarian, M., Hilton, J., Nakano, R., Hesse, C. & Schulman, J. Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.14168 (2021).

18. Creel, K. & Hellman, D. The Algorithmic Leviathan: Arbitrariness, Fairness, and Opportunity in Algorithmic Decision-Making Systems. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 1–18 (2022).

19. Du, N., Huang, Y., Dai, A. M., Tong, S., Lepikhin, D., Xu, Y., Krikun, M., Zhou, Y., Yu, A. W., Firat, O., et al. Glam: Efficient scaling of language models with mixture-of-experts in International Conference on Machine Learning (2022), 5547–5569.

20. Eneanya, N. D., Boulware, L., Tsai, J., Bruce, M. A., Ford, C. L., Harris, C., Morales, L. S., Ryan, M. J., Reese, P. P., Thorpe, R. J., et al. Health inequities and the inappropriate use of race in nephrology. Nature Reviews Nephrology 18, 84–94 (2022).

21. Esteva, A., Chou, K., Yeung, S., Naik, N., Madani, A., Mottaghi, A., Liu, Y., Topol, E., Dean, J. & Socher, R. Deep learning-enabled medical computer vision. NPJ digital medicine 4, 1–9 (2021).

22. Feng, S. Y., Khetan, V., Sacaleanu, B., Gershman, A. & Hovy, E. CHARD: Clinical Health-Aware Reasoning Across Dimensions for Text Generation Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.04191 (2022).

23. Garg, S., Perot, V., Limtiaco, N., Taly, A., Chi, E. H. & Beutel, A. Counterfactual fairness in text classification through robustness in Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (2019), 219–226.

24. Gebru, T., Morgenstern, J., Vecchione, B., Vaughan, J. W., Wallach, H., Iii, H. D. & Crawford, K. Datasheets for datasets.

Communications of the ACM 64, 86–92 (2021).

25. Gu, Y., Tinn, R., Cheng, H., Lucas, M., Usuyama, N., Liu, X., Naumann, T., Gao, J. & Poon, H. Domain-specific language model pretraining for biomedical natural language processing. ACM Transactions on Computing for Healthcare (HEALTH) 3, 1–23 (2021).

26. Gu, Y., Han, X., Liu, Z. & Huang, M. Ppt: Pre-trained prompt tuning for few-shot learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.04332 (2021).

27. Guidance, W. Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health. World Health Organization (2021).

28. Han, X., Zhao, W., Ding, N., Liu, Z. & Sun, M. Ptr: Prompt tuning with rules for text classification. AI Open (2022).

29. Hendrycks, D., Burns, C., Basart, S., Zou, A., Mazeika, M., Song, D. & Steinhardt, J. Measuring massive multitask language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.03300 (2020).

30. Hoffmann, J., Borgeaud, S., Mensch, A., Buchatskaya, E., Cai, T., Rutherford, E., Casas, D. d. L., Hendricks, L. A., Welbl, J., Clark, A., et al. Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.15556 (2022).

31. Hong, Z., Ajith, A., Pauloski, G., Duede, E., Malamud, C., Magoulas, R., Chard, K. & Foster, I. ScholarBERT: Bigger is Not Always Better. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.11342 (2022).

32. Hooker, S. Moving beyond “algorithmic bias is a data problem”. Patterns 2, 100241 (2021).

33. Jin, D., Pan, E., Oufattole, N., Weng, W.-H., Fang, H. & Szolovits, P. What disease does this patient have? a large-scale open domain question answering dataset from medical exams. Applied Sciences 11, 6421 (2021).