When considering browsers, people generally think of Chrome, Firefox, and Edge, but the real power lies in the engines that run underneath these browsers. The engines ultimately dictate how your browser looks, feels, and what it’s capable of doing on the internet: they are not seen, but they are foundational. Even though we have several browsers, the web currently runs on a handful of engines: Google’s Blink, Apple’s WebKit, and Mozilla’s Gecko, as well as highly divergent forks like Goanna (used by Pale Moon).

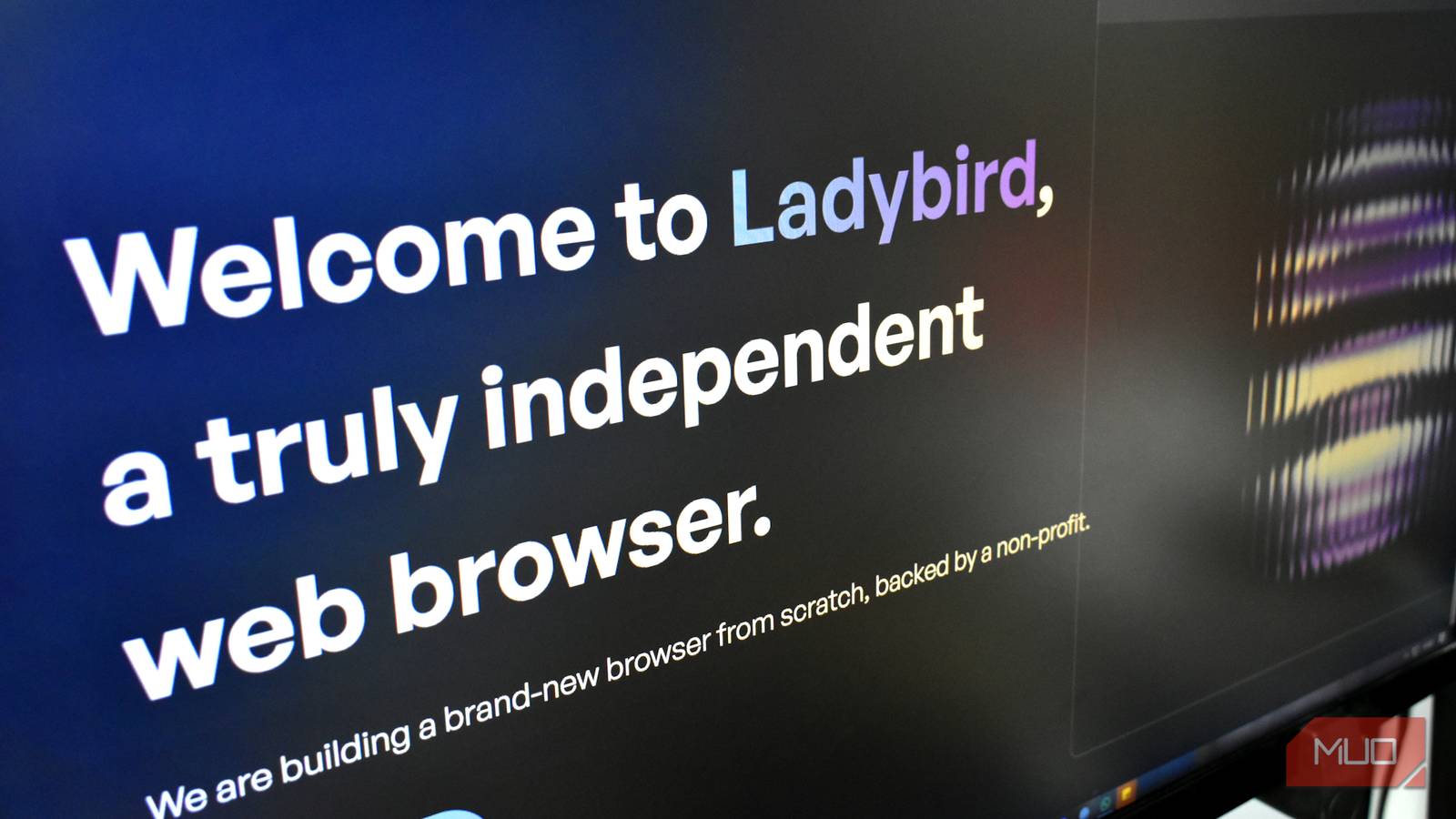

But there is a new challenger in town that’s really catching my eye: the LadyBird project. It’s a new engine built from scratch and is currently suitable for developer experimentation. It’s currently in heavy development and aims for a public alpha release in 2026, though this timeline remains subject to change as development progresses. What’s more exciting is that it aims to be a truly independent web browser, running on a novel web engine. We can hope that this will lead to new web innovations, better competition, and increased user control. This project is funded primarily by private sponsorships, and maybe, finally, the debate won’t be Chrome vs. Edge, or Firefox vs. Vivaldi, but something totally new.

What is the LadyBird engine?

A new browser engine is rare

In the early 2000s, several browser engines were available, including Trident (Internet Explorer), Presto (Opera), Gecko, and WebKit, among others. Over time, many of the original engines died or merged. Opera killed Presto for Blink in 2013, then in 2019, Microsoft abandoned Trident/EdgeHTML for Chromium. Today, we have just three major ones, and of the three, Blink holds the largest market share among browser engines, powering popular browsers such as Chrome, Brave, and Edge.

After the historical thinning of web browser engines, it’s been rare to hear of new ones. But engines are very important because they dictate the rules for what web developers can do. Blink dominates, with Chrome holding about 69% of the entire desktop market share, according to StatCounter. When a certain engine dominates, it becomes more likely to dictate standards, optimizations, and compatibility quirks. And less competition breeds less innovation.

However, as necessary as it is, a new browser engine is rare due to the difficulty of building one. It must pass tens of thousands of compatibility tests and perfectly handle HTML, CSS, JavaScript, graphics, security, accessibility, and performance at web scale. Adding the sheer cost of expertise needed to build one makes it understandable why no one has ventured into this space in more than a decade.

LadyBird’s goal is monumental because it isn’t forking any of the existing browser engines; it’s completely independent. An independent browser engine gives hope for fresh decisions and browsers free of legacy baggage. It may never dominate market share or topple Blink, but at least it breaks the perception that it’s impossible to build a browser engine from scratch.

While LadyBird avoids legacy code from Chromium or Gecko, it draws some architectural inspiration from existing projects like WebKit and Qt, though all code is newly written.

LadyBird’s radical approach

Building from scratch without Chromium DNA

The browser industry is approaching a monoculture, with the dominant share being Chromium-based browsers. LadyBird leverages modern C++ standards (C++20 and beyond) to create a clean, modular architecture separated into independent libraries, promoting maintainability and safety.

Its core is divided into independent libraries such as LibWeb (rendering), LibJS (JavaScript), LibWasm (WebAssembly), and LibGfx (graphics), among others, which handle essential browser engine components separately. This modular approach helps the team avoid accumulated technical debt, prioritize safety, readability, and maintainability, and also makes LadyBird a reference for educational purposes—engineers can study it without wading through millions of lines of legacy code.

Browser engines like Blink and WebKit have had instances where they implemented features under pressure from their corporate backers. The Electronic Frontier Foundation reported on Google’s attempt to define the future of advertising through FLoC. That and the EFF’s report on Apple’s unilateral effort to restrict tracking via Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP) are examples of these feature implementations. However, LadyBird is taking a different approach, one that strictly follows web standards rather than succumbing to market pressures.

Additionally, there are decades of quirks in Chromium and Gecko that are carried along to maintain compatibility with older sites. LadyBird’s approach avoids these historical hacks and focuses on clean implementations of modern standards. This should make it lighter and potentially more secure.

The challenges facing LadyBird

Web compatibility has been the downfall of engines

Technical elegance is not the only requirement for a web engine to succeed. It must be able to render the messy, real-world web. Websites sometimes depend on undocumented quirks in established engines like Blink or WebKit. This is a challenge because if LadyBird implements the official W3C web standards, websites coded to suit these quirks may break. This makes web compatibility one of LadyBird’s biggest challenges.

Compatibility is a key factor that determines whether a project gains legitimacy, even with a small user base, and it is measured through formalized tests, such as WPT (Web Platform Tests). These tests are co-developed by browser vendors, and LadyBird will only gain respect in the standards discussion if it can keep up.

But there is a deeper complexity to the compatibility challenge. Users will typically stick to browsers that render everything correctly, and developers will focus on optimizing for what users have. If LadyBird does not have significant adoption, websites will not take the time to test it. A lack of compatibility means users will not switch. This cycle has been the ruin of browser engines in the past.

It affects us all

LadyBird’s success matters to you

As long as you don’t live off-grid, a new browser engine is a big deal for the web, and it affects us all. The success of the project isn’t only about adding a new browser, but also about introducing the possibility of changing web standards. We currently have a handful of corporations dictating how the web evolves. An independent engine like LadyBird could rebalance the dynamic and help ensure that a single company’s priorities don’t dominate the internet.

My fear is limited adoption of the project, but even that strengthens the web’s resilience. One more independent engine helps make the ecosystem less fragile. Its very existence pressures Google, Apple, and Mozilla to justify their decisions, improve transparency, and possibly accelerate innovation to maintain their edge.

Being independent means the project isn’t locked to any particular ecosystem. It could be ported to devices and operating systems that are somewhat neglected by mainstream engines. Haiku OS, SerenityOS, and RISC‑V-based devices are some that come to mind.

An independent browser engine is exciting

The roadmap for LadyBird is ambitious, with an alpha release planned for 2026, a beta release for 2027, and a stable public release scheduled for 2028. It’s impossible to say if it will hit all the targets, but having an independent browser engine on the horizon is exciting nonetheless.

I stopped trusting Firefox, and Brave is the only Chromium browser I still trust. Maybe by 2028, LadyBird will be another option worth using. Until then, I’m optimistic we’ll get a browser that’s quite different from the current bunch.