Table of links

Abstract

1 Introduction

2 Is an ethnographic study the right choice?

- The context of your research

- The kind of research questions you want to answer

- What ethnographic studies require from the researcher

3 Planning an ethnographic study

- Finding a site for field work

- Participant or non-participant observation

- Duration of field work

- Space and Location

- Theoretical underpinning

4 Implementing your ethnographic study

- Gaining access and starting up

- Handling your preconceptions

- During the study

- Going Native

- Leaving the field

5 From Data to Text

- Reflective and inductive analysis

- Writing Ethnography for Software Engineering Audiences – Reporting the Results

6 Ethnography and Research Ethics

7 Final comments, Further reading and References

3 Planning an ethnographic study

3 Planning an ethnographic study

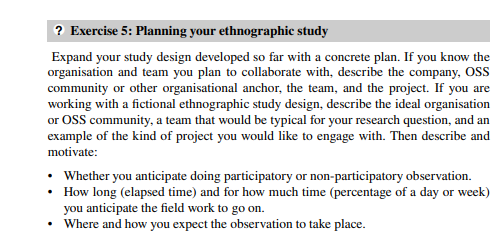

Ethnography belongs to the category of flexible research designs [47], where both the research focus and the concrete field work are expected to be adapted during the research process. However, this does not imply that planning is redundant. An ethnographic study still needs to be planned. It is important that both the researcher and the practitioners have a shared understanding about what might happen once the researcher joins the project. In addition, the plans should be regularly revisited and adapted, and everybody kept aligned throughout the research.

3.1 Finding a site for field work

One of the first things is to identify a suitable project to collaborate with. Often, the ethnographic study would have been prepared by prior contact between the researcher, the company and relevant members of the development team. In other cases, the ethnographic researcher might identify a company or an open source project that fits with the research interest and question.

When working with a company, the ethnographic study might affect their work, so the company and the project team need to agree to the study and the plan. As ethnography is an extremely flexible way of doing research, good communication with the project and in many cases the management of the company is needed to allow for coordination and replanning. One way of doing this is to create a ‘steering committee’ for the research collaboration, consisting of the researcher, the PI of the project, a project contact, and the person responsible for the research collaboration in the company. This committee would meet regularly to discuss whether changes to the logistics of the field work are needed, and to make sure that resources necessary for the ethnographic study (access to documents, code and the like, time for interviews etc) are provided. Exactly how this group works will depend on the field site circumstances but regular alignment across all parties will keep the study on track. In other cases, the researcher could decide to become part of an open source community. This in turn will require deciding on the role in the community the researcher would want to take. Are you able to and interested in participating in the Open Source development, i.e. coding? Could you contribute in other ways to the community? Open source members, especially if they take on core roles like maintainers, are often as busy as members of corporate software engineering teams. Either your contribution to the community during the field work or the research results could be received as a return for the time the community members spend with you. Planning the ethnographic study needs to take research ethics into account as well. Due to the complexity of this topic, research ethics are discussed on their own in Section 6. The following discusses five dimensions to consider when planning an ethnographic study, especially in software engineering.

3.2 Participant or non-participant observation

The best way to understand the culture and practices of a community under study, is to become part of that community. Studying software engineering practices as a software engineer often allows for participation. For example, the researchers can become members of open source communities by participating in the development. However, commercial companies may not be so happy for researchers to be modifying their code, and highly specialised software – for example software for modelling hydraulic systems [61] – requires an expertise that software engineering researchers would normally not master. In such cases, the researcher needs to find a role that allows them to observe and become a culturally competent member of the community. One way could be to act as a newly employed project member, an apprentice in the specific development context. In the above case of hydraulic simulation software, that required expertise in differential equations on a PhD level, the field worker took on documenting the architecture of the re-engineered software to support its usage and customisation. Another example was in an early ethnographic study where

the researcher took on an administrative role [37]. Both of these examples resulted in the researcher getting embedded in the work of the team in a way that was acceptable to all concerned. Deciding the role of the researcher in the field needs to be taken together with the collaborating project team. Also other stakeholders like management and in some cases even clients of the organisation need to be consulted. It will not always be possible to participate in the development and a more passive observation may be the only option. In this case the researcher will sit quietly and observe, listen and take notes but then it is important to keep alert for particularly pertinent activity.

3.3 Duration of field work

How much time does the researcher need to spend with the software team? In our presentation of published ethnographic studies [51], there was a wide variety of field work durations. The traditional answer of ethnographers would be: until the researcher can act as a competent member of the culture, or until the researcher stops learning new things. As in other qualitative research methods, saturation of the observations is an indication for ending an ethnographic study. Here, the overlap of expertise when researching software engineering practices as a software engineering researcher might shorten the time necessary: although the specific software practices might be new, the field worker shares a common ground with the observed teams in the form of shared professional expertise. However, saturation might not be possible, e.g. if a software development project ends before saturation is reached. On the other hand, iterative processes such as agile software development might allow repeated observation of all relevant practices in a comparatively short time. In many situations, it is not necessary to spend all the time with the observed projects. For example, the field worker might choose to spend 3 or 4 days each week with the project, which enables the researcher to start analysing the field material in parallel with the field work. That way the field work duration can be adjusted to fit with time periods that are meaningful from the point of view of the researched practices.

3.4 Space and Location

Ethnographic field work should take place where the culture and practices that are studied take place. But where does software development take place? Software development is both anchored in the physical world, where software developers are located, and it takes place in the digital realm, where the software is located. Observations often need to combine physical observation and an understanding of how the physical actions relate to the development environment, digital documents,changes to and management of the source code, as well as the effects on the deployed software.

Especially when cooperation and collaboration in distributed development is the focus of an ethnographic study, participatory observation on only one side risks neglecting the remote conditions for collaboration. To address this potential bias, multi-site ethnography emphasises the need to do ethnographic field work on all the locales involved. Multi-sited ethnography entails the researcher entering and being accepted at different sites which might require longer stays, e.g. one or more weeks, at all places where relevant project members or stakeholders are situated. As an additional challenge, especially after the lockdowns due to the pandemic in 2020 and 2021, many companies moved from co-located or distributed development to hybrid work organisations, where developers partly work from home, leading not only to distributed but dispersed development, where every member of the team is in a different location [52]. Coordination and cooperation in these circumstances more and more resemble Open Source development. Ethnographic research here has to follow the way software development is organised. One of the core challenges with researching at least partially virtual activities, is that it might be hard to follow an activity in a complex distributed development environment that both has physically visible parts, e.g. workstation layout and virtual elements, e.g. changes to code and deployed software. For example Begum [3] describes the handling of a bug report: the bug report comes into existence through registration of the bug by a support engineer, followed by reproduction of the erroneous behaviour and a root cause analysis by a software engineer who prepares the discussion of the defect in a triage meeting, which in turn results in a strategy to fix the defect. The correction of the defect might again require collaboration between different teams responsible for different parts of the product. To understand what is discussed at the different meetings and to understand the rationale behind decisions might require at least a superficial understanding of the organisation of the source code.

Ethnographic field work here can follow an artefact, e.g. a bug report or the software architecture documentation, or it might focus on the activities of individuals, e.g. the software architect of (a part of) the software, or a group of developers. Different forms of ”virtual ethnography” have been developed as a way to observe internet based cultures (e.g. [29, 33, 43] ). Regardless of how well the field work is planned and prepared, even in smaller projects, the ethnographer will not be able to observe all relevant activities that are going on. Observations might need to be complemented with other data collection methods, like informal, in situ interviews, semi structured more formal interviews, or group interviews, e.g. in the form of a project retrospective.

3.5 Theoretical underpinning

Ethnography often is seen as a bottom-up research method where the development of themes and concepts is based on reflective and inductive analysis. Theories are then developed by comparing results of several ethnographic studies. In order to relate ethnographic studies with each other, the themes and concepts developed in earlier studies have to be connected to the field work and analysis of the later studies, and this can be done via theory. One example is the social theory of learning by Lave and Wenger [34]: comparing findings from widely varying studies led to the formulation of a set of related concepts, a theory. This theory can then be used either as a focus for the field work in new ethnographic studies exploring social learning in different contexts, or to discuss the analysis of field material when peer learning emerges in the reflective and inductive analysis. Theories can be seen as tools to think with rather than a claim for quantifiable correlations that are or can be supported by experiments. For example, the social theory of learning talks about ‘communities of practice’ [34] as an important facilitator to develop and maintain expertise in professional environments. ‘Communities of practice’ as a phenomenon can be identified both through the way members refer to each other and how knowledge is shared with new colleagues and among established members. Using the concept, for example, to understand the onboarding of novices in a software engineering team, can help to structure and focus the observations in the field.

A danger of using theory from the outset, though, is that the focus that a theory provides can become a bias in the empirical work. It can prevent the researcher from paying attention to aspects of the observed practices that do not fit the theory. To prevent theory-based biases, the same techniques used for other biases can be applied (see this chapter, section 4.2). Ethnography researches software development teams as sub-cultures or as social practices. Social theories that focus on social practices and how they reflexively constitute social structure therefore might fit well with the observations and findings and help to develop relevant insights. There are several such practice theories. For example, activity theory [19] focuses on how human goal-directed activity is mediated by tools and also by rules, distribution of labour, and community. Activity theory has for example been used to better understand tool support for distributed development [60]. Dittrich et al [16] and Dittrich [14], use Schatzki’s [50] concept of social practices and Knorr Cetina’s [7] concept of epistemic practices as inspiration to understand the evolution and design of software development practices. Here, the way members of a software team adopt and adapt methods is at the core of the research. Distributed cognition [31] emphasises the distributed nature of cognitive systems and focuses on collaborative work and the use of artefacts and representations. It results in an event-driven description which emphasises information and its propagation through the cognitive system under study. This has been used, for example, to understand how the structure of story cards and agile boards support collaboration [54] and how UX information is handled by agile development teams.

The decision to consider theoretical frameworks can be taken based on the research intent, for example if the intent is to design and improve tools, the use of a theoretical framework that provides a vocabulary to identify and discuss the role of tools can be an advantage. As mentioned above, theory can also be used to interpret the data afterwards, e.g. Sharp et al. [56] used cognitive dimensions to analyse representations that were collected using distributed cognition as a framework. Giuffrida and Dittrich’s article [25] provides an example where ethnographic research is used to develop theory. They further develop concepts from coordination and communication theory to explain widely different success rates of student projects in distributed student projects. The initial analysis showed that successful projects used the Instant Messaging channel Skype provided to not only coordinate but also agree on coordination. In order to explain both what was going on and the differences, Genre theory and concepts based on articulation and coordination theory were combined and further developed.

:::info

Authors:

- Yvonne Dittrich

- Helen Sharp

- Cleidson de Souza

:::

:::info

This paper is available on arxiv under CC by 4.0 Deed (Attribution 4.0 International) license.

:::