Table Of Links

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

- Memory Tagging Extension

- Speculative Execution Attack

3. Threat Model

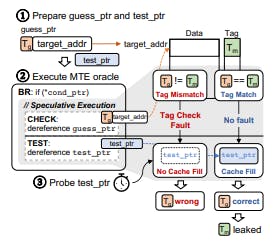

4. Finding Tag Leakage Gadgets

- Tag Leakage Template

- Tag Leakage Fuzzing

5. TIKTAG Gadgets

- TIKTAG-v1: Exploiting Speculation Shrinkage

- TIKTAG-v2: Exploiting Store-to-Load Forwarding

6. Real-World Attacks

6.1. Attacking Chrome

7. Evaluation

8. Related work

9. Conclusion And References

TIKTAG Gadgets

In this section, we present TIKTAG gadgets discovered by the tag leakage template and fuzzing (§4). Each gadget featuring unique memory access patterns leaks the MTE tag of a given memory address. TIKTAG-v1 (§5.1) exploits the speculation shrinkage in branch prediction and data prefetching, and TIKTAG-v2 (§5.2) leverages the blockage of store-to-load forwarding. We further analyze the root cause and propose mitigations at hardware and software levels.

5.1. TIKTAG-v1: Exploiting Speculation Shrinkage

During our experiment with the MTE tag leakage template (§4.1), we observed that multiple tag checks in CHECK influence the cache state of testptr. With a single tag check, testptr was always cached regardless of the tag check result. However, with two or more tag checks, test_ptr was cached on tag match, but not cached on tag mismatch.

In summary, we found that the following three conditions should hold for the template to leak the MTE tag:

(i) CHECK should include at least two loads with guess_ptr;

(ii) TEST should access test_ptr (either load or store, dependent or independent to CHECK); and

(iii) CHECK should be close to BR (within 5 CPU cycles) while TEST should be far from CHECK (more than 10 CPU cycles away). If these conditions are met, testptr is cached on tag match and not cached on tag mismatch. If any of these is not met, testptr is either always cached or never cached. Based on this observation, we developed TIKTAG-v1, a gadget that leaks the MTE tag of any given memory address.

==Gadget.== Figure 2 illustrates the TIKTAG-v1 gadget. In BR, the CPU mispredicts the branch result and speculatively executes CHECK. In CHECK, guessptr is dereferenced two or more times, triggering tag checks with Tg against Tm. GAP provides the time gap between BR and TEST, and then in TEST, testptr is accessed. GAP can be filled with various types of instructions, such as computational instructions (e.g., orr, mul) or memory instructions (e.g., ldr, str), as long as it provides more than 10 CPU cycles of the time gap.

==Experimental Results.== We found that TIKTAG-v1 is an effective MTE tag leakage gadget on the ARM Cortex-X3 (core 8 of Pixel 8 devices) in both MTE synchronous and asynchronous modes. We leveraged the physical CPU cycle counter (i.e., PMCCNTR_EL0) for time measurement, which was enabled by modifying the Linux kernel. An L1 cache hit is determined if the access latency is less than or equal to 35 CPU cycles.

In a real-world setting, the virtual CPU cycle counter (i.e., CNTVCTEL0) is available to the user space with lower resolution, which also can effectively observe the tag leakage behavior. We experimented to measure the cache hit rate of testptr after executing TIKTAG-v1.

To verify condition

(i), we varied the number of loads in CHECK (i.e., Len(CHECK)) from 1, 2, 4, and 8. To verify condition

(ii), we varied the types of memory access in TEST (i.e., independent/dependent, load/store). To verify condition

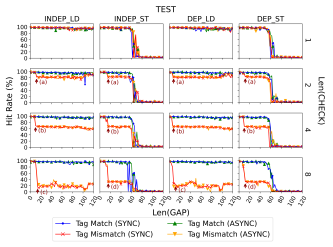

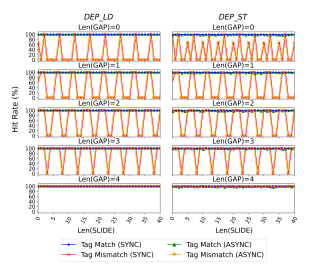

(iii), we filled GAP with a sequence of orr instructions (where each orr is dependent on the previous one) and varied its length (i.e., Len(GAP)). Figure 3 shows the experimental results. The x-axis represents Len(GAP) and the y-axis represents the cache hit rate of test_ptr measured over 1,000 trials.

When Len(CHECK) was 1, the cache hit rate of testptr had no difference between tag match and mismatch. testptr was either always cached (i.e., load access) or cached until a certain threshold and then not cached (i.e., store access). When Len(CHECK) was 2 or more, depending on the tag check result, the cache hit rate differed, validating the condition

(i). If the tag matched, the cache hit rate was the same as when Len(CHECK) was 1. If the tag mismatched, the cache hit rate dropped compared to the tag match (annotated with arrows). This difference was observed in all access types of TEST, validating the condition

(ii). The cache hit rate drop was observed after about 10 orr instructions in GAP. Further experiments inserting lengthy instructions between BR and CHECK (§E) confirmed that CHECK should be close to BR, validating the condition

(iii). When the tag mismatched, the cache hit was periodic and the period got shorter as Len(CHECK) increased. When Len(CHECK) is 2, a cache hit occurred in 5 out of 6 trials (83%, arrows (a)). When Len(CHECK) is 4, a cache hit occurred in 2 out of 3 trials (66%, arrows b).

When Len(CHECK) is 8, the pattern differed between load and store accesses (arrows c and d). For store access, a cache hit was observed every 3 trials (33%, arrows c). For load access, the pattern changed over iterations from all cache hits (0%) to a cache hit every 2 trials (50%) (arrows d). A similar cache hit rate drop was observed when guess_ptr points to an unmapped address and generated speculative address translation faults. This further indicates that TIKTAG-v1 can be utilized as an address-probing gadget [20] useful for breaking ASLR.

==Root Cause.== Analyzing the gadget, we found that tag check results affect the CPU’s data prefetching behavior and the

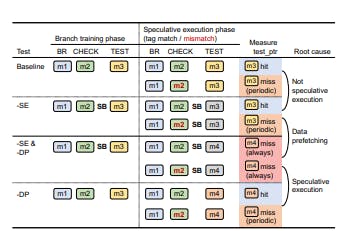

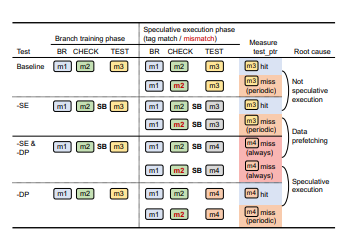

speculative execution. This refutes the previous studies on speculative MTE tag leakage [22, 38], which stated that tag check faults do not affect the speculation execution and did not state the impacts of the data prefetching. In general, modern CPUs speculatively access memory in two cases: speculative execution [30] and data prefetching [10, 19]. To identify the root cause of TIKTAG-v2 in these two cases, we conducted an ablation study (Figure 4).

First, we eliminated the effect of speculative execution by inserting a speculation barrier (i.e., sb) between CHECK and TEST. Second, we varied the memory access pattern between branch training and speculative execution phases to eliminate the effect of data prefetching. In Baseline, no speculation barrier was inserted, and both branch training and speculative execution phases accessed the same addresses in order. In this case, test_ptr was cached on tag match, but not cached on tag mismatch.

In -SE, a speculation barrier was inserted to prevent TEST from being speculatively executed. Here, the same cache state difference was observed, indicating that the difference in Baseline is not due to the speculative execution at least in this case. Next, in -SE & -DP, the memory access pattern was also varied in the speculative execution phase to prevent testptr from being prefetched. As a result, testptr was always not cached, verifying that the CPU failed to prefetch test_ptr due to the divergence in the access pattern. If we compare -SE and -SE & -DP, the cache state difference was observed only when data prefetching is enabled (-SE).

Considering the CPU’s mechanism, such a difference seems to be due to data prefetching—i.e., the CPU prefetches data based on the previous access pattern, but skips it on tag mismatch. Finally, in -DP, we removed the speculation barrier to reenable the speculative execution of TEST while still varying the memory access pattern. In this case, the difference is observed again between tag match and mismatch. Comparing -DP and -SE & -DP, we can conclude that the speculative execution is also the root cause of the cache difference—i.e.,

the CPU halts speculative execution on tag check faults. We suspect that the CPU optimizes performance by halting speculative execution and data prefetching on tag check faults. A relevant patent filed by ARM [12] explains that the CPU can reduce speculations on wrong path events [9], which are events indicating the possibility of branch misprediction, such as spurious invalid memory accesses. By detecting branch misprediction earlier, the CPU can save recovery time from wrong speculative execution and improve the data prefetch accuracy by not prefetching the wrong path-related data.

Since these optimizations are beneficial in both MTE synchronous and asynchronous modes, we think that the tag leakage behaviors were observed in both MTE modes. We also think there is a time window to detect wrong path events during speculative execution upon branch prediction, which seems to be 5 CPU cycles. As explained in the patent [12], the CPU may maintain speculation confidence values for speculative execution and data prefetching.

We think the CPU reduces the confidence values on tag check faults, halts speculation if it drops below a certain threshold, and restores it to the initial level. This reasoning explains the periodic cache miss of testptr on tag mismatch, where the confidence value is repeatedly reduced below the threshold (i.e., cache miss) and restored (i.e., cache hit). In addition, when TEST is store access, the speculation barrier made testptr always not cached. This indicates that the CPU does not prefetch data for store access, thus the speculation window shrinkage is the only root cause in such cases.

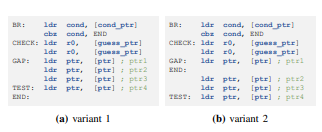

==Variants.== Running the tag leakage fuzzer (§4.2), we discovered variants of TIKTAG-v1 leveraging linked list traversal (Figure 5). Before the gadget, a linked list of 4 instances is initialized, where each instance points to the next instance (i.e., ptr0 to ptr3), and the cache line of the last instance (ptr3) is flushed. The gadget traverses the linked list by accessing ptr0 to ptr3 in order, where TEST accesses ptr3 only if the branch result is true. After the gadget, the cache hit rate of ptr3 is measured.

In the first variant (Figure 5a), TEST is located in the true branch of the conditional branch BR. In the second variant (Figure 5b), TEST is located out of the conditional branch path, where both the true and false branches merge. In both variants, if the tag matched in CHECK, ptr3 was cached, but not cached if the tag mismatched, as in the original TIKTAG-v1 gadget (Figure 3). We think the root cause is the same as the original gadget—i.e., the CPU changes speculative execution and data prefetching behaviors

on tag check faults. Moreover, the variants can be effective in realistic scenarios like linked list traversal, and the tag leakage can also be observed from the memory access outside the conditional branch’s scope. Mitigation. TIKTAG-v1 exploits the speculation shrinkage on tag check faults in speculative execution and data prefetching. To prevent MTE tag leakage at the micro-architectural level, the CPU should not change the speculative execution or data prefetching behavior on tag check faults.

To prevent TIKTAG-v1 at the software level, the following two approaches can be used.

i) Speculation barrier: Speculation barrier can prevent the TIKTAG-v1 gadget from leaking the MTE tag. If TEST contains store access, placing a speculation barrier (i.e., sb) or instruction synchronization barrier (i.e., isb) makes test_ptr always not cached, preventing the tag leakage. If TEST contains load access, placing the barrier before TEST does not prevent tag leakage, but placing it before CHECK mitigates tag leakage, since speculative tag check faults are not raised.

ii) Padding instructions: TIKTAG-v1 requires that tag check faults are raised within a time window from the branch. By inserting a sequence of instructions before CHECK to extend the time window, the CPU does not reduce the speculations and test_ptr is always cached (§E).

5.2. TIKTAG-v2: Exploiting Store-to-Load Forwarding

Inspired by Spectre-v4 [45] and LVI [67] attacks, we experimented with the MTE tag leakage template to trigger store-to-load forwarding behavior [61]. As a result, we discovered that store-to-load forwarding behavior differs on tag check result if the following conditions hold:

(i) CHECK triggers store-to-load forwarding, and

(ii) TEST accesses memory dependent on the forwarded value. If the tag matches in CHECK, the memory accessed in TEST is cached; otherwise, it is not cached.

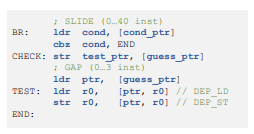

Based on this observation, we developed TIKTAG-v2. Gadget. Figure 6 illustrates the TIKTAG-v2 gadget. The initial setting follows the MTE tag leakage template (§4.1), where the CPU mispredicts the branch BR and speculatively executes CHECK and TEST. At CHECK, the CPU triggers store-toload forwarding behavior by storing testptr at guessptr and immediately loading the value from guess_ptr as ptr.

If CHECK succeeds the tag checks (i.e., Tg matches Tm), the CPU forwards testptr to ptr and speculatively accesses testptr in TEST. If CHECK fails the tag checks (i.e., Tg mismatches Tm), the CPU blocks testptr from being forwarded to ptr and does not access testptr.

==Experimental Results.== TIKTAG-v2 showed its effectiveness as an MTE tag leakage gadget in ARM Cortex-A715 (core 4-7 of Pixel 8). We identified one requirement for TIKTAGv2 to exhibit the tag leakage behavior: the store and load instructions in CHECK should be executed within 5 instructions. If this requirement is met, the cache hit rate of test_ptr after TIKTAG-v2 exhibited a notable difference between tag match and mismatch (Figure 7).

Otherwise, the store-toload forwarding always succeeded and the CPU forwarded testptr to ptr, and testptr was always cached. To verify the requirement, we conducted experiments by inserting two instruction sequences, SLIDE and GAP (Figure 6). Both sequences consist of bitwise OR operations (orr), each dependent on the previous one, while not changing register or memory states. SLIDE is added before the gadget to control the alignment of store-to-load forwarding in the CPU pipeline.

GAP is added between the store and load instructions in CHECK to control the distance between them. The results varying SLIDE from 0 to 40 and GAP from 0 to 4 are shown in Figure 7. In each subfigure, the x-axis represents the length of GAP, and the y-axis represents the cache hit rate of testptr after the gadget, measured over 1000 trials. On tag match, the cache hit rate of testptr was near 100% in all conditions. However, on tag mismatch, the hit rate dropped on every 5 instructions in SLIDE.

With Len(GAP)=0 (i.e., no instruction), the hit rate drop was most frequent, occurring in 4 out of SLIDE length. With Len(GAP)=1,2,3, the hit rate drop occurred in 3, 2, and 1 times every 5 instructions in SLIDE, respectively. With Len(GAP)=4, no hit rate drop was observed. Similarly to TIKTAG-v1, the blockage of store-to-load forwarding was not specific to the MTE tag check fault, but was also observed with address translation fault, thus TIKTAG-v2 can also be utilized as an address-probing gadget.

==Root Cause.== The root cause of TIKTAG-v2 is likely due to the CPU preventing store-to-load forwarding on tag check faults. The CPU detects the store-to-load dependency utilizing internal buffers that log memory access information, such as Load-Store Queue (LSQ), and forwards the data if the dependency is detected. Although there is no documentation detailing the store-to-load forwarding mechanism on tag check faults, a relevant patent filed by ARM [7] provides a hint on the possible explanation.

The patent suggests that if the store-to-load dependency is detected, the load instruction can skip the tag check and the CPU can always forward the data. If so, store-to-load forwarding would not leak the tag check result (i.e., data is forwarded both on tag match and mismatch), as observed when Len(GAP) is 4 or more. When Len(GAP) is less than 4, however, the store-to-load succeeded on tag match and failed on tag mismatch.

We suspect that the CPU performs the tag check for the load instruction if the store-to-load dependency is not detected, and the CPU blocks the forwarding on tag check faults to prevent meltdown-like attacks [36, 41]. Considering the affected core (i.e., Cortex-A715) dispatches 5 instructions in a cycle [55], it is likely that the CPU cannot detect the dependency if the store and load instructions are executed in the same cycle, since the store information is not yet written to the internal buffers.

If Len(GAP) is 4 or more, the store and load instructions are executed in the different cycles, and the CPU can detect the dependency. Therefore, the CPU skips the tag check and always forwards the data from the store to load instructions. If Len(GAP) is less than 4, the store and load instructions are executed in the same cycle, and the CPU fails to detect the dependency and performs the tag check for the load instruction. In this case, the forwarding is blocked on tag check faults.

==Mitigation.== To prevent tag leakage in TIKTAG-v2 at the micro-architectural level, the CPU should be designed to either always allow or always block the store-to-load forwarding regardless of the tag check result. Always blocking the store-to-load forwarding may raise a performance issue. Instead, always allowing forwarding can effectively prevent the tag leakage with low-performance overheads. This would not introduce meltdown-like vulnerabilities, because tag mismatch occurs within the same exception level.

At the software level, the following mitigations can be applied to prevent TIKTAG-v2.

i) Speculation barrier: If a speculation barrier is inserted before CHECK, the CPU does not speculatively execute storeto-load forwarding on both tag match and mismatch. Thus, test_ptr is not cached regardless of the tag check result.

ii) Preventing Gadget Construction: If the store and load instructions in CHECK are not executed within 5 instructions, the store-to-load forwarding is always allowed on both cases, making test_ptr cached always. The potential gadgets can be modified to have more than 5 instructions between the store and load instructions in CHECK, by adding dummy instructions (e.g., nop) or reordering the instructions.

:::info

Authors:

- Juhee Kim

- Jinbum Park

- Sihyeon Roh

- Jaeyoung Chung

- Youngjoo Lee

- Taesoo Kim

- Byoungyoung Lee

:::

:::info

This paper is available on arxiv under CC 4.0 license.

:::