In September 2017, Gabriella Uwadiegwu stepped into the Orange County Convention Centre in Orlando, Florida, and saw the future. The hall, packed with 25,000 women attending that year’s Grace Hopper Celebration, pulsed with life. The Grace Hopper Celebration, launched in June 1994, is one of the world’s largest gatherings of women technologists.

The air buzzed with possibility: Melinda Gates, among other prominent women, took to the stage to champion the transformative impact of women in innovation. Recruiters from big tech companies like Google and Amazon flashed polished smiles and interview forms. And a group of women from She++ spoke of a world where tech belonged to everyone. It was thrilling and overwhelming. “Imagine going to a Beyoncé concert and you’ve never attended a concert before,” Uwadiegwu said.

She’d grown up in Lagos, a city where dreams were big but often out of reach. At 18, she immigrated to the U.S., landing at a Manhattan community college, where she studied computer science. She recalls feeling like an outsider at first. “We were four or five women, maybe two or three Black,” she recalled.

Her classroom was a microcosm of the STEM world. Women occupy only 25% of tech roles, according to a 2023 Forbes report. Black women hold only 2% of tech roles in the U.S.. Particularly for immigrants, language hurdles, cultural disconnects, lack of a network, and financial strain complicate access even further. Uwadiegwu was adapting to a world where the odds were stacked against her, until that serendipitous attendance at the Grace Hopper Conference changed everything.

At the event, the 20-something Nigerian immigrant was among a few Black women in the crowd —more than she’d ever seen in her Manhattan classrooms. Before she knew it, she was interviewing with Square, chatting with Google and Amazon recruiters, and accepting invitations to tour tech facilities of prestigious universities like Stanford. The scale of it all was dizzying—opportunity wasn’t just an abstract idea here; it was tangible, a currency passed from hand to hand. Yet, as she stood in that hall, a realisation sank in: back in Nigeria, women like her were locked out of this orbit, not for lack of talent, but for lack of access.

The Grace Hopper epiphany: Access levels the playing ground

Uwadiegwu didn’t secure an internship at her first Grace Hopper conference. But she got an opportunity to tour Stanford University, where she saw disorienting ambition among the students. “I’m meeting a Stanford freshman, and she’s programming electric leggings, and it feels so unreal.”

She recalls feeling a pang of regret for not taking her SATs seriously—due to a lack of preparation, she tells me, she had failed the exam thrice before scoring just enough to attend her community college. “But just being around [the Stanford students], I could feel the ambition too.”

Yet, amidst the dizzying displays of privilege and cutting-edge research, she began to notice something fundamental. “They weren’t much different from me,” she mused.

The chasm, she realised, wasn’t in innate ability but in “placement of opportunity.” Stanford, she observed, simply offered “access to a vast amount of things.” It’s a crucible where the air itself seems to crackle with intelligence, compelling everyone to rise to the occasion. “You’re around very smart, ambitious people. So you can’t slack,” she explained.

With the weight of her newfound understanding, Uwadiegwu decided to attend Grace Hopper a second time in 2018. Instead of awe at the room and the people in it, she was determined to leave with something, an internship at the very least. She filled out as many forms for interviews as she could. And interviews with multiple companies followed, culminating in an offer from Twitch, the streaming platform Amazon had acquired for about $970 million. Uwadiegwu told me that she only knew the company as the “purple logo” company, but she aced all her interviews and got a job that paid her 75% more than she’d hoped.

This deepened her conviction that lack of access was the real barrier—not talent. “What if I had never studied in the US? How different would my life be?” Someone needed to bring similar opportunities to Nigeria, and that day, she decided it would be her.

In August 2019, she launched WeTech, a non-profit that has cultivated a vibrant virtual community of 5,000 women and organised 10 well-attended events that have connected women to work opportunities in tech.

Raising the bar at Twitch

Before WeTech, Uwadiegwu knew that the access she wanted to provide women technologists in Nigeria required significant financial resources. Her internship at Twitch promised just that. But to thrive at Twitch, she had to contend with the feeling that the odds were stacked high against her: a Black immigrant woman from Nigeria, with a foundational education from a community college, breaking into the hallowed halls of Silicon Valley. At Twitch, she found herself among a cohort of interns from the nation’s most prestigious institutions—Cornell, MIT, and others.

During her 12-week internship, Uwadiegwu was placed in the Android team. They were, she recounted, predominantly male, often Asian or white, with a “dorky” and “dweeb” vibe typical of anime and gaming culture, which she was deeply involved in at the time. Yet, beneath the surface of their academic pedigree and cultural quirks, she recognised a shared drive.

“Being around very smart people,” she explained, “there is this pressure to execute and always show off and toot your own horn.” It was an environment that demanded confidence and adaptability, a constant push to proactively absorb and apply complex information.

Interns are required to build a project before the end of their internship. Uwadiegwu vaguely recalls the specific details of her project. “I think I had a capstone project where I built the first version of a leaderboard for “gifting subscriptions” and “cheering” on live streamers.”

By the end of her tenure, Uwadiegwu had not only met expectations but had, in the words of her manager, “raised the bar for what interns had done,” she tells me on our call. Her work at Twitch not only left her with immense pride but with enough stipend to begin planning WeTech’s inaugural conference in Nigeria.

The first WeTech Conference

“I had already started planning in March 2019, before Twitch,” she said. For eight months, she canvassed for attendees and speakers, cold emailed professionals for support in cash or partnerships, and many of them said no.

Each rejection stung. “[But] I learned how to make a case,” she said. Eventually, a last-minute sponsorship from fintech company, Paga, came.

When November arrived, 50 out of the 80 women who signed up for the event turned up at Four Points Hotel in Lagos. Speakers at the event included the head of the Computer Science department at the University of Lagos, Odunayo Eweniyi, co-founder of fintech company PiggyTech, as well as engineers and product managers who shared their career journeys with the attendees.

“That first event was about advocacy,” Uwadiegwu said. It paled in comparison to the Grace Hopper event, but Uwadiegwu was sure this was just the start of something big. Her sister, Flora Uwadiegwu, believed this too and joined her to plan the next event.

But before the next big conference, Uwadiegwu thought it would be useful to roll out an ambassadorial program that would incentivise women to create “mini WeTech groups” across campuses and small community clusters. The pandemic, however, threw a wrench in those plans. WeTech, her ambitious initiative to support women in tech, found itself in a quagmire. Her vision for a campus ambassador program, complete with stipends and budgets for student-led groups, was now unfeasible in a remote world. “I pressed a little bit of the brake pedal on WeTech,” she admits. Planned in-person programming for WeTech was postponed, and she pivoted to organising a virtual conference for 2020 alongside her sister who was now fully at WeTech as a co-founder.

Another awakening: Archangel Fund

Though WeTech’s progress stalled, Uwadiegwu’s tech career was accelerating. After a successful internship, she returned to Twitch full-time, relocating to the Bay Area. She had also been immersing herself in Silicon Valley’s ecosystem, particularly through Y Combinator (YC), an elite accelerator.

Her connection to Twitch co-founder Michael Seibel, a prominent YC figure, opened doors to various YC events, which fueled her entrepreneurial drive. By 2019, she and her brother had partnered to launch and grow a startup. Seeking advice on scaling the startup and non-profit, Uwadiegwu reached out to Seibel. Their 90-minute conversation made it clear they needed to pivot their business model towards product verification and on-demand delivery. This meant abandoning significant prior investment, a tough decision considering they had bootstrapped so far.

In 2020, despite a surge in venture capital, Uwadiegwu struggled to raise funds for the startup. Observing that a mere 2% of global VC funding goes to women, and less than 0.5% to Black women founders, she grew incensed and resolved to “start investing in women.”

Using $30,000 of her savings, Uwadiegwu launched Archangel Fund, a personal mission to bridge this funding gap. Early investments included Nigerian companies like Termii, RiseVest, Taeillo, and HelliCarrier. After further training with Venture Partners, she’s now invested $200,000-$300,000 through Archangel Fund, backing five companies like Texture Science Labs, Penny, Jetstream Africa, and Goa (Kenya). “Nobody ordained me,” she said, “I just decided I would do it, and that funding has gone into the hands of women building.”

WeTech’s inflexion point: Scaling impact

By 2021, Uwadiegwu was wearing several hats: software engineer, tech investor, and convener of WeTech—all demanding responsibilities, but she did not allow herself to slow down.

WeTech had grown bigger and become a household name among female tech professionals and enthusiasts in Nigeria.

In 2024, its annual conference brought together 1,500 women, a far cry from WeTech’s 50-attendee debut in 2019. Over 3,000 women had applied to attend, she said, and a rigorous vetting process whittled down the number to 1,500, the number of people the Landmark Centre venue could accommodate.

Enough funding was also rolling in to enable the team offer perks like free transportation, meals, and daycare for at least five mothers who were attending. Strategic partnerships were also delivering results: HerTech, a platform that offers tech skills training for women, signed up 600 women for free. Women-founded startups landed funding and placements at hubs and fellowships through the conference. The event also provided free LinkedIn headshots, resume reviews, and on-site job interviews, with recruiters actively seeking to hire. Some attendees even secured funding directly from investors present at the event, Uwadiegwu said.

Its conferences in the two years prior had introduced women founders into accelerator programs, transforming the organisation’s events into a launchpad for Nigerian women in tech.

But this scale did not come on a platter.

Navigating logistics from the U.S. in the middle of a career change was difficult. As was ensuring that the event remained free to attend for women in a country where 63% of the population is multidimensionally poor. “It didn’t make sense for us to charge, given the extreme situation of Nigeria,” she said.

So far, Uwadiegwu has bootstrapped WeTech with her sister, Flora, supported by funding from tech institutions that see the value in their mission. However, she believes over-reliance on donor funding is not a sustainable path for the organisation. With a vibrant community that has grown to 10,000 women and a team of 10, WeTech is now embarking on its next major frontier: developing and monetising a tech product.

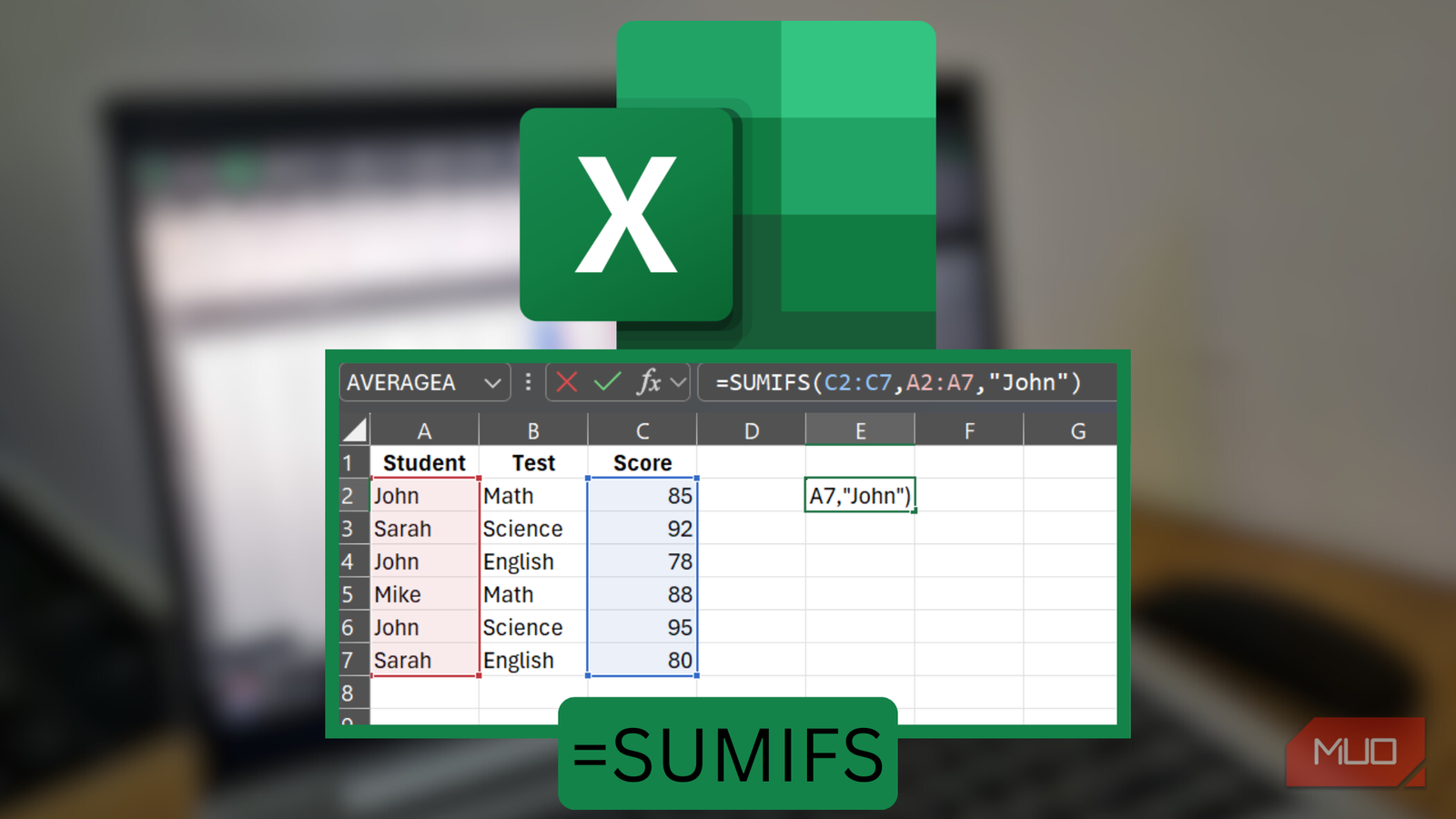

Uwadiegwu says the product is still in stealth, but the platform aims to match women in their network with tech jobs in ways that ensure bias-free hiring. This ambitious project, coupled with ongoing scholarship programs (like the current one for 500 women in partnership with Grow with Google, an initiative that provides certified digital skills training), mentorship initiatives, and a strategic two-year conference planning cycle, signals WeTech’s deepening impact and its long-term plans.

“The future here is amazing,” Uwadiegwu says.

WeTech, she believes, is currently in the midst of its “inflexion point,” a transformative period that will cement its role as a powerful catalyst for economic and societal change across Africa.

The personal toll: Balancing passion and pressure

Uwadiegwu’s ambition for gender inclusion has continued with significant personal and financial sacrifice. To keep up, she has navigated a demanding tech career, often fraught with its pressures. After her initial successful stint at Twitch, she embarked on a new chapter with Spade, an early-stage startup backed by prestigious venture firms like Andreessen Horowitz.

While the opportunity was exciting, it demanded an intense commitment, with Uwadiegwu routinely clocking 60-hour workweeks.

Her experience there offered a stark lesson on the demands of the albeit lucrative jobs at venture-backed startups: “It means that your life is that thing that you have taken money for. That is what it means. It means your life.”

Her career path also brought the harsh realities of the tech industry into sharp focus. After nearly two years at Carta, a company specialising in cap table management for startups, she faced the upheaval of a tech layoff in December 2023. Now, she works at Headspace, where she is a backend engineer building an AI product for a mental health companion, a role that offers the flexibility of remote work and a company culture she deeply appreciates for its mindfulness and respect for personal time.

Through all these professional twists and turns, WeTech has remained a steadfast anchor.

Uwadiegwu says WeTech’s vision is imbued with a strong feminist ethos, citing the influence of figures like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, whose work on feminist values resonates deeply within the WeTech community. Beyond career networks, women come to find lasting friendships and invaluable support that go beyond their careers. She sees it in the profound passion of her team, many of whom are young women who volunteer their time without pay.

“Sometimes I feel like I could cry,” she admitted.

The future of WeTech and Africa’s GDP

Uwadiegwu stands at the precipice of WeTech’s most ambitious chapter yet. Her gaze is firmly set on the 2026 conference, an event already in meticulous planning over a year in advance, designed to surpass the impact of its predecessors, as well as the launch of its talent matching tool.

Her conviction remains in “overcorrecting” gender imbalance in tech by aggressively investing in women across all sectors can fundamentally transform Africa’s economy. This is what fuels her relentless drive: that she and her team are building a more equitable and prosperous future for women and Africa.

“My goal right now—maybe it’s very ambitious— is to shift Africa’s GDP with the work that we’re doing.”

Mark your calendars! Moonshot by is back in Lagos on October 15–16! Join Africa’s top founders, creatives & tech leaders for 2 days of keynotes, mixers & future-forward ideas. Early bird tickets now 20% off—don’t snooze! moonshot..com