The US Senate passed the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) on Wednesday after congressional leaders earlier this month stripped the bill of provisions designed to safeguard against excessive government surveillance. The “must-pass” legislation now heads to President Joe Biden for his expected signature.

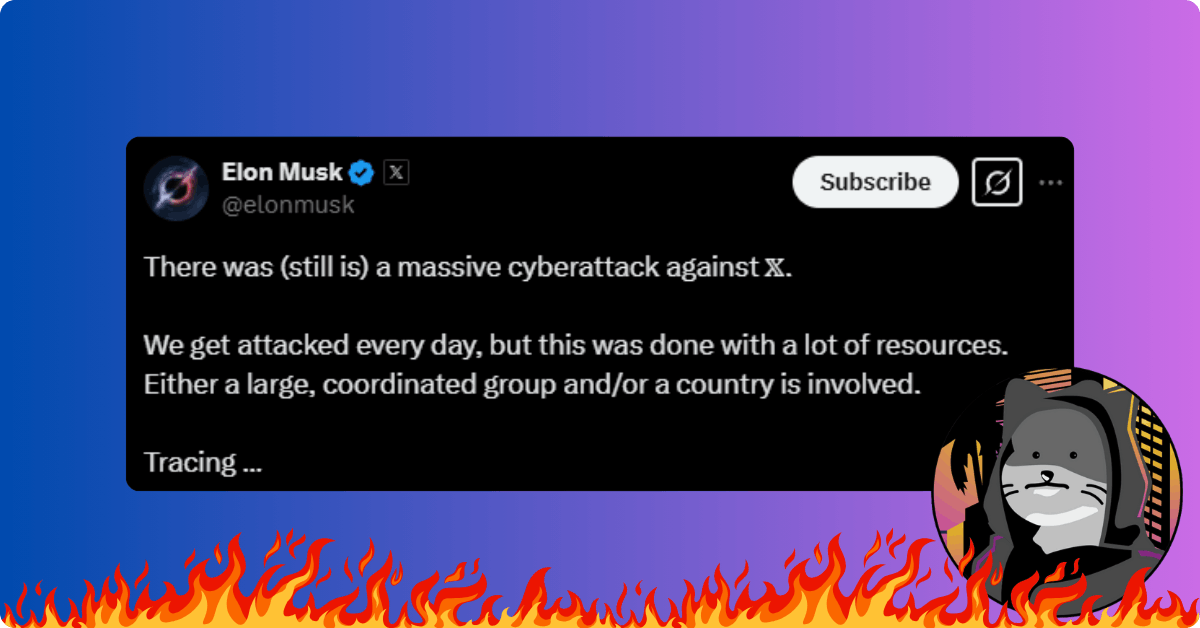

The Senate’s 85–14 vote cements a major expansion of a controversial US surveillance program, Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). Biden’s signature will ensure that the Trump administration opens with the newfound power to force a vast range of companies to help US spies wiretap calls between Americans and foreigners abroad.

Despite concerns about unprecedented spy powers falling into the hands of controversial figures such as Kash Patel, who has vowed to investigate Donald Trump’s political enemies if confirmed to lead the FBI, Democrats in the end made little effort to rein in the program.

The Senate Intelligence Committee first approved changes to the 702 program this summer with an amendment aimed at clarifying newly added language that experts had cast as dangerously vague. The vague text was introduced into the law by Congress in April, with Democrats in the Senate promising to correct the issue later this year. Ultimately, those efforts proved to be in vain.

Legal experts began issuing warnings last winter over Congress’s efforts to expand FISA to cover a vast range of new businesses not originally subject to Section 702’s wiretap directives. While reauthorizing the program in April, Congress changed the definition of what the government considers an “electronic communications service provider,” a term applied to companies that can be compelled to install wiretaps on the government’s behalf.

Traditionally, “electronic communications service providers” refers to phone and email providers, such as AT&T and Google. But as a result of Congress redefining the term, the new limits of the government’s wiretap powers are unclear.

It is widely assumed that the changes were intended to help the National Security Agency (NSA) target communications stored on servers at US data centers. Due to the classified nature of the 702 program, however, the updated text purposefully avoids specifying which types of new businesses will be subject to government demands.

Marc Zwillinger, one of the few private attorneys to testify before the nation’s secret surveillance court, wrote in April that the changes to the 702 statute mean that “any US business could have its communications [wiretapped] by a landlord with access to office wiring, or the data centers where their computers reside,” thus expanding the 702 program “into a variety of new contexts where there is a particularly high likelihood that the communications of US citizens and other persons in the US will be ‘inadvertently’ acquired by the government.”