November 10, 2025 • 10:00 am ET

Czechia’s policy on China: Swinging between engagement and de-risking

This is the ninth chapter of the report “Is Europe waking up to the China challenge? How geopolitics are reshaping EU and transatlantic strategy.” Read the full report here.

Although Czechia emerged as one of the EU’s early hawks and whistleblowers on China, its overall stance has shifted markedly over the past two decades—oscillating between engagement and balancing. These fluctuations were largely driven by domestic political divisions and sustained Chinese influence efforts. Controversies surrounding Chinese investments accelerated Czechia’s rise as a leading advocate of economic security and “de-risking.” Within the EU, the country has distinguished itself through a forward-looking approach to technological risk management grounded in anticipatory policy principles, although implementation has been uneven. Over the past decade, its approach has alternated between neglect and assertiveness in response to political shifts, economic pressures, and changing perceptions of China’s role in Europe.

High-level engagement with Taiwan has remained a cornerstone of Czechia’s strategy to counter Beijing’s influence, while Czech civil and political actors have grown increasingly vigilant about Chinese interference. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—openly supported by China—Prague’s security posture has hardened further. The 2023 security strategy and the 2025 foreign policy framework codified this shift, defining China as a systemic challenge across economic, technological, diplomatic, and security dimensions. However, with the return of Andrej Babiš to power after the October 2025 elections, Czechia’s China policy could once again swing back toward engagement.

Early Czechia-China relations

Initial Czech perceptions of China were decisively shaped in 1989 by two pivotal and sharply divergent historical moments: Czechoslovakia’s anti-communist Velvet Revolution and China’s violent suppression of the Tiananmen protests. These twin events produced a lasting moral and political contrast. Over the following two decades, both the Czech public and political elite came to view China as a state that had abandoned liberalization and reverted to authoritarian Communism, while the newly independent Czech Republic defined its post-communist identity through democratization and human-rights advocacy. This divergence was personified by former dissident and first democratic President Václav Havel, whose foreign policy prioritized human rights and solidarity with political prisoners in China and elsewhere. Czechia’s frequent criticism of China’s human rights violations, along with the Dalai Lama’s 2009 visit to Prague, prompted China to freeze diplomatic communications with the country until 2012.

In the early 2010s, Czech policy toward China underwent a sharp reversal, driven by Beijing’s expanding influence efforts and the rise of pro-China forces within Czech politics. In 2012, Czechia joined the “16+1” format— a Chinese initiative to promote business and investment relations between China and Central and Eastern European countries—marking the start of a decade-long rapprochement. The election of Miloš Zeman as president in 2013, followed by his Social Democratic Party government in 2014, consolidated this pro-engagement trajectory. Under Zeman, Czechia joined the Belt and Road Initiative in 2016, coinciding with Xi Jinping’s landmark visit to Prague—the first by a Chinese head of state—which produced a “strategic partnership” agreement. During the Zeman era, bilateral ties deepened through high-level visits—Zeman visited China seven times between 2013 and 2020—and high-profile Chinese investments, particularly by the Shanghai-based CEFC China Energy, whose chairman became one of Zeman’s economic advisers, and by the PPF Group, led by Czech billionaire Petr Kellner. Yet these ventures soon drew scrutiny over political influence and opaque financing, and both ultimately collapsed, underscoring the limits of the Czech-Chinese rapprochement.

From the late 2010s onward, Czech policy toward China entered a new phase marked by growing skepticism and assertive distancing. During this period, Czechia emerged as one of Europe’s early advocates of “de-risking” from China, and its senior officials undertook high-profile visits to Taiwan and deepened bilateral cooperation with the island—moves that elicited sharp reactions from Beijing. In 2019, Prague’s mayor terminated the capital’s sister-city agreement with Beijing, symbolizing the shift in public and political attitudes. The 2021 parliamentary elections further consolidated this turn: voters ousted the traditionally pro-China Social Democrats and Communists from parliament, electing Petr Fiala’s center-right coalition— including the China-critical Pirate Party—which adopted a distinctly hawkish line toward Beijing. The election of Petr Pavel to the presidency in 2023 reinforced this orientation. His 2025 visit to Taiwan—the first by a European head of state—brought Sino-Czech relations to a historic low. Yet political volatility persists. Following the October 2025 elections, former Prime Minister Andrej Babiš is returning to power and is expected to form a coalition with far-right parties such as Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD) and Motorists for Themselves, potentially steering Czechia’s China policy back toward engagement and continuing the cyclical pattern that has long characterized Czechia’s stance on Beijing.

Trade and investment: Chinese acquisitions and domestic backlash

Trade between Czechia and China is substantial but highly asymmetrical. Imports from China reached €36.7 billion in 2024, compared to exports of €3.0 billion, leaving a deficit of €33.7 billion. Machinery, electronics, and consumer goods dominate imports, while Czech exports remain modest, concentrated in intermediate goods and automotive products. Large Czech manufacturers such as Škoda maintain operations in China, but policymakers have never treated these ties as strategically critical dependencies.

Czechia’s economic relations with China have mirrored the broader oscillation in its China policy between engagement and caution. During the Zeman era, two major Chinese investment episodes—initially promoted as symbols of strategic partnership—ultimately provoked domestic backlash and deepened skepticism toward Beijing. The first was CEFC China Energy’s 2015 move into the Czech market. With support from President Zeman, the Shanghai-based conglomerate—reportedly linked to the Chinese Communist Party and the People’s Liberation Army—rapidly acquired stakes in prominent Czech companies, including Czech Airlines, Lobkowicz Brewery, soccer club SK Slavia Prague, the Central European investment group J&T, the advertising firm Médea, and several landmark Prague properties. Zeman’s decision to appoint CEFC chairman Ye Jianming as his economic adviser further fueled controversy. Investigations by Czech media and think tanks soon raised concerns over opaque financing and political influence. These fears intensified in 2018 when Ye was detained in China for alleged economic crimes and CEFC was absorbed by the Chinese state-owned CITIC Group, giving Beijing indirect control over key Czech media holdings.

The second case involved the PPF Group, a major Czech investment conglomerate led by billionaire Petr Kellner. PPF’s ventures channeling Chinese investments into Czech telecommunications, finance, and media—alongside cooperation with Zeman in cultivating business ties with China and Russia—were widely perceived as part of a broader influence network. Coverage in PPF-friendly media often portrayed Chinese investment favorably while adopting critical tones toward the United States and the EU. However, Kellner’s death in a 2021 helicopter crash ended the company’s China-focused expansion.

Together, the CEFC and PPF cases came to epitomize the risks of politically driven economic engagement with China. Beyond these scandals, the Czech public was generally disappointed that most Chinese investment promises never materialized. The combination of these factors eroded the perception of economic partnership as a foreign-policy success and bolstered calls for a more guarded, security-focused stance toward Chinese capital.

Drawing lessons from the scandals surrounding CEFC and PPF, Czech authorities began to construct one of Central Europe’s most comprehensive frameworks for screening and managing foreign economic influence. As a result, Czechia had already taken its first concrete steps toward de-risking, well before the EU formally embraced the concept of economic security. In 2018, the Czech National Bank blocked CEFC’s planned $1 billion acquisition of a majority stake in the financial group J&T—which operated subsidiaries across Slovakia, Croatia, Russia, and Barbados—on the grounds of opaque funding sources. The intervention reflected a growing institutional awareness of financial and strategic vulnerabilities associated with Chinese capital—particularly since the European Central Bank had already approved the deal.

Building on this experience, Czechia adopted the Foreign Investment Screening Act in May 2021, creating a robust national mechanism to vet acquisitions in sensitive sectors such as defense, critical infrastructure, and advanced data services. The law empowers authorities to approve, condition, or block transactions where risks cannot be mitigated, and its consistent enforcement has earned recognition as a model within the EU. The Mercator Institute for China Studies has cited the Czech FDI regime as an example for other member states to follow.

Czechia has also extended this vigilance to the research domain: universities and funding agencies now apply strict research-security guardrails, systematically screening partnerships for dual-use and technology-transfer risks. Collectively, these measures have positioned Czechia as a regional frontrunner in translating early lessons from Chinese investment controversies into durable instruments of national and European economic security.

A central pillar of Czechia’s de-risking efforts has been the deepening of its economic ties with Taiwan, whose investments in the country now exceed China’s several times over. The flagship example of this growing relationship is the expansion of Taiwanese electronics manufacturer Foxxconn into Czechia, where its subsidiary Foxconn CZ employs five thousand workers and ranks as the sixth-largest corporation in the country by revenue.

Technology: De-risking amid uneven enforcement

Czechia has also stood out among EU member states for its pioneering efforts in technological de-risking, which are both anticipatory and risk-based, although the execution of its policies has shown inconsistencies. Cybersecurity emerged as a prominent concern in Czech efforts to strengthen technological resilience. In December 2018, the National Cyber and Information Security Agency (NÚKIB) issued a warning about potential risks associated with Chinese technology suppliers, including Huawei and ZTE. The decision to publish the alert without prior government clearance sparked a political controversy in Prague, involving President Zeman, Prime Minister Babiš, opposition leaders, and NÚKIB officials. Zeman called NÚKIB’s warning unsubstantiated—and Babiš eventually fired NÚKIB’s director. Although the agency had briefed the government and intelligence services prior to publication, it could never fully explain its unilateral decision to make the warning public without cabinet consent. The domestic tensions caused by this move quickly spilled into foreign policy, with the Chinese embassy denouncing the warning as unfounded and demanding an official apology. This, in turn, prompted a public exchange of statements between Babiš and the Chinese ambassador that further strained bilateral relations.

As a result of the NÚKIB scandal, Czech media and the public turned on Huawei, and the backlash spilled over to affect PPF, which had made a deal with Huawei to build a 5G network for its telecom subsidiary O2. Public pressure forced PPF to withdraw from the agreement and instead contract Ericsson to build the 5G network. Czech telecom operators subsequently diversified their suppliers for 5G infrastructure.

Czech political actors have also played a role in European and international cybersecurity cooperation. Backed by Prime Minister Babiš, the city of Prague hosted the 5G Security Conference 2019—and during its EU Presidency in 2022, Czechia hosted a high-level cybersecurity conference with representatives from over eighty countries. Moreover, the country’s EU Commissioner Věra Jourová served as Commissioner for Values and Transparency between 2019 and 2024, overseeing portfolios on cyberspace security and the fight against disinformation.

However, implementation of technological de-risking from China has been uneven. Czechia’s leading telecom companies—T-Mobile, Vodafone, and O2—have continued to use Huawei technology. Czech state institutions, including the police and Czech state television, are bound by law to select the lowest bidder for technology procurement, and some have therefore accepted bids from Chinese companies such as Huawei and ZTE.

Nevertheless, Czechia has taken a series of proactive measures to limit its technological exposure to China’s coercive or opaque practices. For example, authorities excluded China from the public tender for the expansion of the Dukovany nuclear power plant. In 2025, Czech authorities attributed cyber operations targeting the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to Chinese actors and banned the use of any products by the Chinese artificial intelligence (AI) startup DeepSeek in state administration. That same year, NÚKIB issued a warning on personal-data transfers, expanding the scope of oversight to include data governance. Some of Czechia’s cybersecurity measures, including its computer emergency response teams, have set benchmarks within the EU and can serve as examples for other member states to follow.

Czechia has also demonstrated a clear preference for working with trusted allies on technology issues. Partnerships with Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea are framed both as values-driven alliances and as practical vehicles for modernizing Czech industry. Cooperation spans semiconductors, precision machinery, and talent development, including Taiwanese semiconductor facilities in Prague and Brno. This networked approach reflects a long-standing Czech strategy: collaborate with trusted democracies on sensitive technologies while minimizing exposure to Chinese supply chains.

Security: China as a systemic challenge, Taiwan as an ally

Czechia’s security policy has evolved in tandem with broader government policy toward China over the decades. While pro-China governments historically did not regard Beijing as a malign actor in Central Europe, more recent administrations have adopted a balancing approach and actively pushed back against Chinese operations.

Taiwan has long been a pillar of Czechia’s strategic balancing against China. In 2019, the Prague city council canceled a partnership agreement with Beijing and signed a new pact with Taipei, despite retaliatory measures by China. A year later, Senate President Miloš Vystrčil visited Taiwan and delivered his “I am Taiwanese” speech, provoking Beijing and prompting threats against Czech companies operating in China. In 2023, lower-house Speaker Markéta Pekarová Adamová led a large delegation that signed eleven memoranda of understanding in Taipei, followed by additional agreements on industrial development and semiconductors in 2024 and 2025. The Taiwanese foreign minister visited Prague in both 2021 and 2023—and following his election in January 2023, President Petr Pavel accepted a congratulatory phone call from Taiwan’s president Tsai Ing-wen. This was a first for a European head of state and drew further criticism from Beijing. Pavel’s August 2025 visit with the Dalai Lama ultimately prompted China to sever ties with the Czech president entirely.

Czech civil society has also engaged with the security challenges that China poses. Universities have tightened vetting of foreign partnerships, particularly with Chinese institutions, to reduce risks of espionage or undue influence. NGOs and think-tanks, such as China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe—a Czech organization focused on analyzing China’s political and economic influence—play a key role in sustaining informed debate on the risks posed by Chinese engagement. Academia, NGOs, municipalities, and media have collectively fostered a critical stance toward China, informed by historical memory of authoritarian great-power domination.

Czech intelligence has consistently flagged China as a source of espionage and influence operations. The annual reports of the Czech Security Information Service highlight Chinese use of academic and business channels to cultivate access. NÚKIB’s 2018 warning on Huawei and ZTE marked a milestone in European cybersecurity, compelling operators of critical infrastructure to assess risks well ahead of the EU’s 5G Toolbox. Subsequent actions extended vigilance to software and data: in May 2025, Prague attributed a multi-year cyber-espionage campaign against its foreign ministry to APT3, a network of Chinese state-sponsored intelligence officers, contract hackers, and support staff; in July 2025, the Czech telecom regulator restricted the use of the Chinese DeepSeek AI model in high-risk infrastructure; and in September 2025, NÚKIB issued a warning on the transfer of personal data to China. Together, these measures demonstrate Czechia’s consistent treatment of China as a security and intelligence threat.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—which has been backed by China—Czech security policy has hardened further toward Beijing. The Czech government has deprioritized the Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries—in fact, Foreign Minister Jan Lipavský declared the “club” effectively dead for Central Europe in 2023. Czechia’s 2023 security strategy and the 2025 foreign policy framework codify what had already become the de facto guiding principle of Czech foreign and security policy under the Fiala government: namely, that China represents a systemic challenge across economic, technological, diplomatic, and security dimensions.

In the 2023 strategy, China is explicitly identified as a global “systemic challenge,” not only due to its influence operations in democratic states, but also because of its pursuit of alternative norms for the international order. The document situates China and Russia jointly as actors seeking to weaken European unity and the rules-based system, framing Czechia’s response in terms of resilience, institutional vigilance, and a whole-of-society approach. The strategy elevates economic security alongside cyber, internal, and defense domains as central arenas of strategic concern, signaling that techno-economic dependencies, supply-chain vulnerabilities, and investment-driven influence have become mainstream considerations in threat assessment.

The 2025 foreign policy framework builds directly on that security doctrine, embedding the logic of “security first” across diplomatic, economic, and normative fronts. It underscores that safeguarding the state and its citizens is now the central objective of Czech foreign policy and places economic and technological security at the heart of external relations. In mapping the strategic environment, the framework highlights that challenges today are not solely military but also technological, geoeconomic, and ideological—thereby linking security to both national interest and global competition. By doing so, the framework institutionalizes longstanding Czech practice: engagement with external actors is now assessed against resilience, reciprocity, and risk mitigation rather than purely economic or diplomatic opportunity.

Together, these documents signal a qualitative shift: China is no longer seen merely as a partner or competitor, but as a structural challenge intersecting with Europe’s strategic agenda. The integration of economic security into the core of Czech foreign and security doctrines reinforces the idea that Czechia aims to convert episodic reactive measures into a durable strategic posture toward China.

Czechia’s alignment with the EU’s China policy

Czechia’s stance on EU economic security and de-risking policies has shifted considerably over the past decade—alternating between periods of engagement and strategic balancing—reflecting the country’s polarized domestic politics, competing economic interests, and evolving perceptions of Chinese influence. These shifts are best understood across two distinct phases: the 2013-2021 period, shaped by Zeman’s pro-China governments and marked by selective alignment and strategic ambiguity, and the period since 2021, under more hawkish leadership, defined by closer convergence with Brussels and a pragmatic approach to balancing.

During Zeman’s decade in office, backed by Social Democratic and ANO-led coalitions, Czechia’s engagement with China complicated its alignment with EU-level de-risking efforts. While Prague voiced rhetorical support for bloc-wide instruments—such as investment screening and export-control coordination—implementation was uneven and politically contested, reflecting domestic divisions and entrenched Chinese influence networks. The government’s focus on attracting Chinese capital dampened advocacy for stricter economic-security safeguards, even as Czech institutions were among the first to develop regulatory tools later adopted at the European level. Analysts note that this duality—public endorsement of resilience frameworks combined with permissive domestic practice—left Czech policy Janus-faced, oscillating between security-driven caution and commercial opportunism.

Despite these inconsistencies, Czechia’s early encounters with CEFC and PPF’s opaque investments fostered an awareness of the risks inherent in strategic dependence and unclear ownership. This recognition informed Prague’s backing for emerging EU instruments such as foreign investment screening and anti-coercion mechanisms, even as political allies of Zeman resisted their enforcement at home. In this sense, Czechia under Zeman anticipated several elements of the EU’s later Economic Security Strategy, though it remained an unreliable advocate for their consistent implementation.

Since 2021, under more hawkish governments, Czechia has shifted decisively toward the European mainstream on de-risking, more closely aligning its rhetoric and instruments with the European Commission’s agenda. It now emphasizes that economic resilience and competitiveness must be advanced through EU-wide mechanisms—such as export controls, research-security standards, and anti-coercion measures—rather than bilateral initiatives.

Still, Czechia’s implementation of this strategy remains pragmatic rather than doctrinaire. In October 2024, the country abstained from a European Council vote on tariffs targeting Chinese electric-vehicle imports, aiming to balance its automotive sector’s exposure with its broader commitment to addressing structural distortions. Officials maintained that only coordinated EU action—not unilateral Czech measures—could effectively counter Chinese state capitalism while preserving European competitiveness. Within Central Europe, Czechia thus occupies the security-conscious end of the policy spectrum, distinguishing itself from member states that initially favored engagement with Beijing.

Across both political cycles, Prague has played a meaningful role in shaping EU frameworks on investment screening, subsidy control, and anti-coercion tools. Yet while its strategic rationale has increasingly converged with Brussels, the consistency of national implementation still hinges on domestic political alignment. The evolution from Zeman’s pro-China engagement to the center-right’s structured balancing underscores how Czechia’s approach to China—and to EU economic-security governance—remains dynamic, adaptive, and politically contested.

About the author

Related Content

Explore the programs

The Global China Hub tracks Beijing’s actions and their global impacts, assessing China’s rise from multiple angles and identifying emerging China policy challenges. The Hub leverages its network of China experts around the world to generate actionable recommendations for policymakers in Washington and beyond.

The Europe Center promotes leadership, strategies, and analysis to ensure a strong, ambitious, and forward-looking transatlantic relationship.

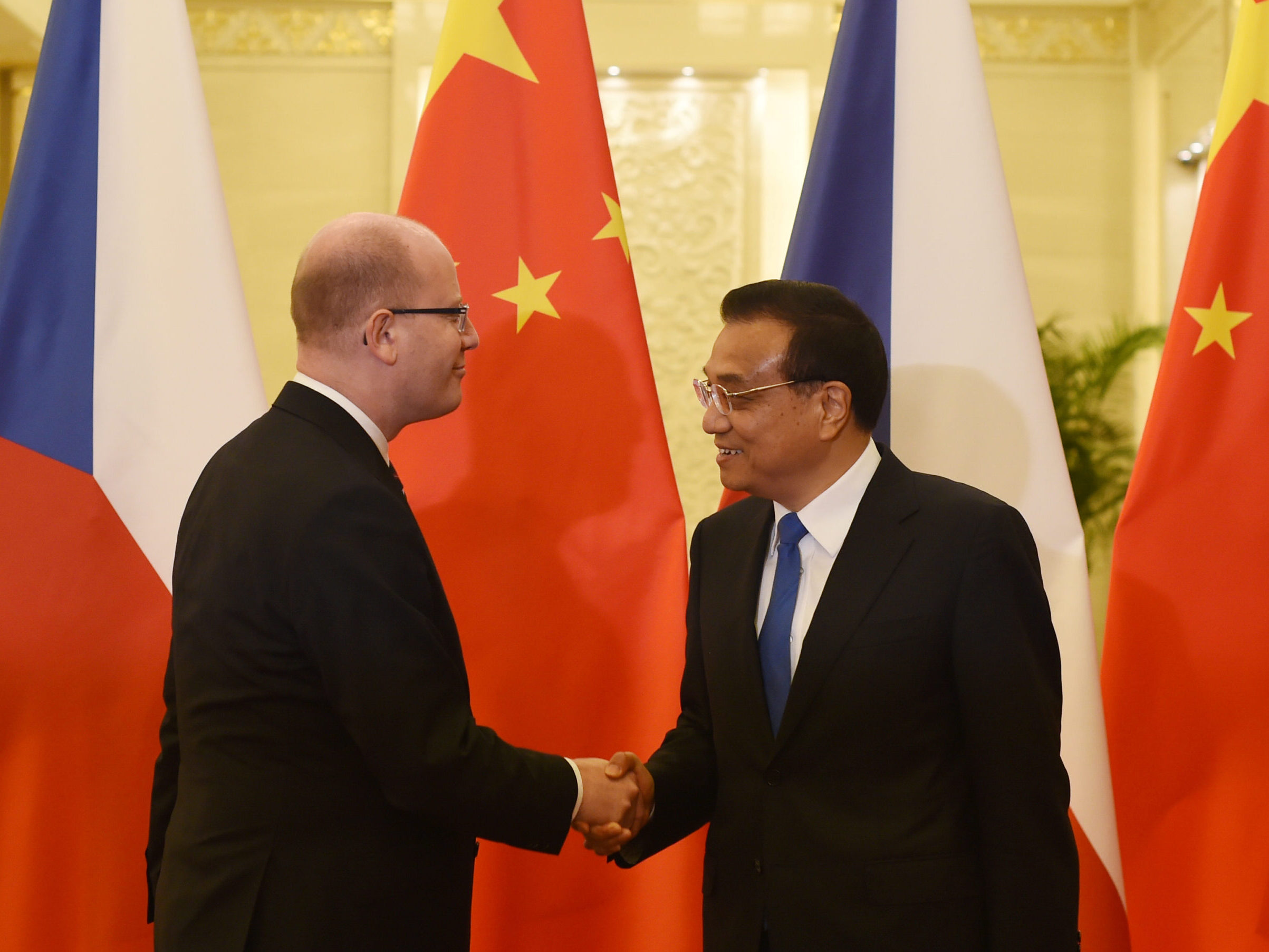

Image: Czech Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka (L) shakes hands with China’s Premier Li Keqiang before a meeting in Beijing, China June 17, 2016. REUTERS/Greg Baker/Pool