So far, Nvidia has provided the vast majority of the processors used to train and operate large AI models like the ones that underpin ChatGPT. Tech companies and AI labs don’t like to rely too much on a single chip vendor, especially as their need for computing capacity increases, so they’re looking for ways to diversify. And so players like AMD and Huawei, as well as hyperscalers like Google and Amazon AWS, which just released its latest Trainium3 chip, are hurrying to improve their own flavors of AI accelerators, the processors designed to speed up specific types of computing tasks.

Could the competition eventually reduce Nvidia, AI’s dominant player, to just another AI chip vendor, one of many options, potentially shaking up the industry’s technological foundations? Or is the rising tide of demand for AI chips big enough to lift all boats? Those are the trillion-dollar questions.

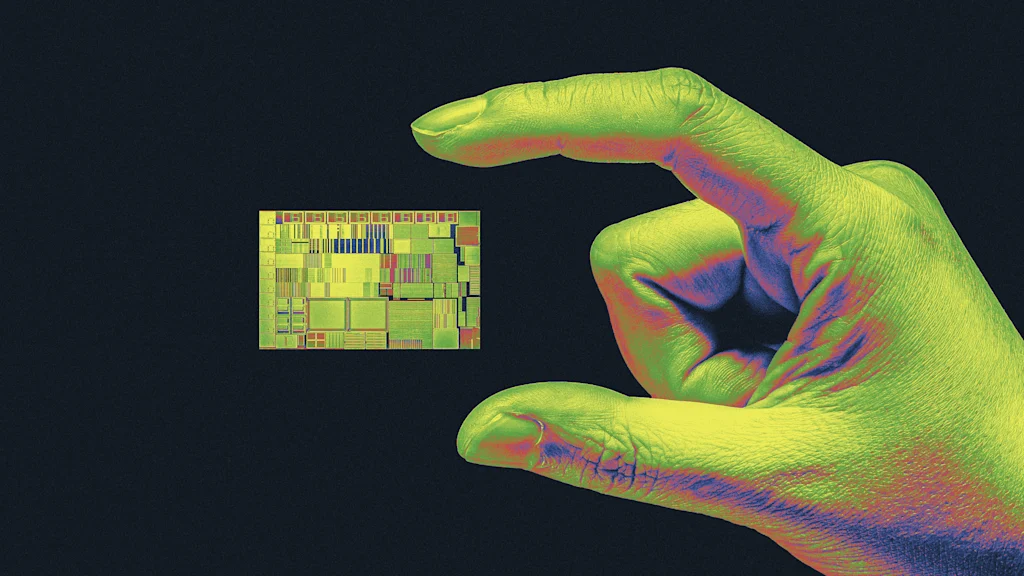

Google sent a minor shockwave across the industry when it casually mentioned that it had trained its impressive new Gemini 3 Pro model entirely on its own Tensor Processing Units (TPUs)—another flavor of AI accelerator chips (GPUs). Industry observers immediately wondered if the AI industry’s broad dependence on Nvidia chips was justified. After all, they’re very expensive: A big part of the billions now being spent to build out AI computing capacity (data centers) is going to Nvidia chips.

And Google TPUs are looking more like an Nvidia alternative. The company can rent TPUs in its own data centers, and it’s reportedly considering selling the chips outright to other AI companies, including Meta and Anthropic. A (paywalled) report from The Information in November said Google is in talks to sell or lease its GPUs so they can run in any company’s data center. A reuters report says Meta is in talks to spend “billions” on Google’s TPUs starting in 2027, and may begin paying to run AI workloads on TPUs within Google data centers even sooner. Anthropic announced in October that it would use up to a million TPUs within Google data centers to develop its Claude models.

Selling the TPUs outright would, technically, put Google in direct competition with Nvidia. But that doesn’t mean that Google is gunning hard to steal Nvidia’s chip business. Google, after all, is a major buyer of Nvidia chips. Google may see selling TPUs to certain customers as an extension of selling access to TPUs running in its cloud.

This makes sense if said customers are looking to do the types of AI processing that TPUs are especially good at, says IDC analyst Brandon Hoff. While Nvidia’s GPUs are workhorses capable of a wide range of work, most of the big-tech platform companies have designed their own accelerators that are purpose-built for their most crucial types of computing. Microsoft developed chips that are optimized for its Azure cloud services. Amazon’s Trainium chips are especially good at e-commerce-related tasks like product suggestion and delivery logistics. Google’s TPUs are good at serving targeted ads across its platforms and networks.

That’s something Google shares with Meta. “They both do ads and so it makes sense that Meta wants to take a look at using Google’s TPUs,” Hoff says. And it’s not just Meta. Most big tech companies use a variety of accelerators because they use machine learning and AI for a wide variety of tasks. “Apple got some TPUs, got some of the AWS chips, of course got some GPUs, and they’ve been playing with what works good for different workloads,” he adds.

Nvidia’s big advantage has been that its chips are very powerful—they’re the reason that training large language models became possible. They’re also great generalists, good for a wide variety of AI workloads. On top of that, they’re flexible, which is to say they can plug in to different platforms. For example, if a company wants to run its AI models on a mix of cloud services, they’re likely to develop those models to run on Nvidia chips because all the clouds use them.

“Nvidia’s flexibility advantage is a real thing; it’s not an accident that the fungibility of GPUs across workloads was focused on as a justification for increased capital expenditures by both Microsoft and Meta,” analyst Ben Thompson wrote in a recent newsletter. “TPUs are more specialized at the hardware level, and more difficult to program for at the software level; to that end, to the extent that customers care about flexibility, then Nvidia remains the obvious choice.”

However, vendor lock-in remains a big concern, especially as big tech companies and AI labs are sinking hundreds of billions of dollars into new data center capacity for AI. AI companies would prefer instead to use a mix of AI chips from different vendors. Anthropic, for one, is explicit about this: “Anthropic’s unique compute strategy focuses on a diversified approach that efficiently uses three chip platforms—Google’s TPUs, Amazon’s Trainium, and NVIDIA’s GPUs,” the company said in an October blog post. Amazon’s AWS says its Trainium3 chip is roughly four times faster than the Trainium2 chip it announced a year ago, and 40% more efficient.

Because of the performance of Nvidia chips, many AI companies have standardized on CUDA, the Nvidia software layer that lets developers control how the GPUs work together to support their AI applications. Most of the engineers, developers, and researchers who work with large AI models know CUDA, which can cause another form of skills-based organizational lock-in. But now it may make sense for organizations to build whole new alternative software stacks to accommodate different kinds of chips, Thompson says. “That they did not do so for a long time is a function of it simply not being worth the time and trouble; when capital expenditure plans reach the hundreds of billions of dollars, however, what is ‘worth’ the time and trouble changes.”

IDC projects that the high demand for AI computing power isn’t likely to abate very soon. “We see that cloud service providers are growing quickly, but their spending will slow down,” Hoff says. Beyond that, a second wave of demand may come from “sovereign funds,” such as Saudi Arabia, which is building the Humain “AI hub,” a large AI infrastructure complex that it will fund and control. Another wave of demand could come from large multinational corporations that want to build similar “sovereign” AI infrastructure, Hoff explains. There’s a lot of stuff in 2027 and 2028 that’ll keep driving demand.”

There are plenty of “chipmaker challenges Nvidia” stories out there, but the deeper one delves into the economic complexities and competitive dynamics of the AI chip market, much of the drama drains away. As AI finds more applications in both business and consumer tech, AI models will be asked to do more and more kinds of work, and each one will demand various mixtures of generalist or specialized chips. So while there is growing competitive pressure on Nvidia, there’s still a lot of good reasons for players like Google and Amazon to collaborate with Nvidia.

“In the next two years, there is more demand than supply so almost none of that matters,” says Moor Insights & Strategy chief analyst Patrick Moorhead. Moorhead believes that five years from now Nvidia GPUs will still retain their 70% market share.