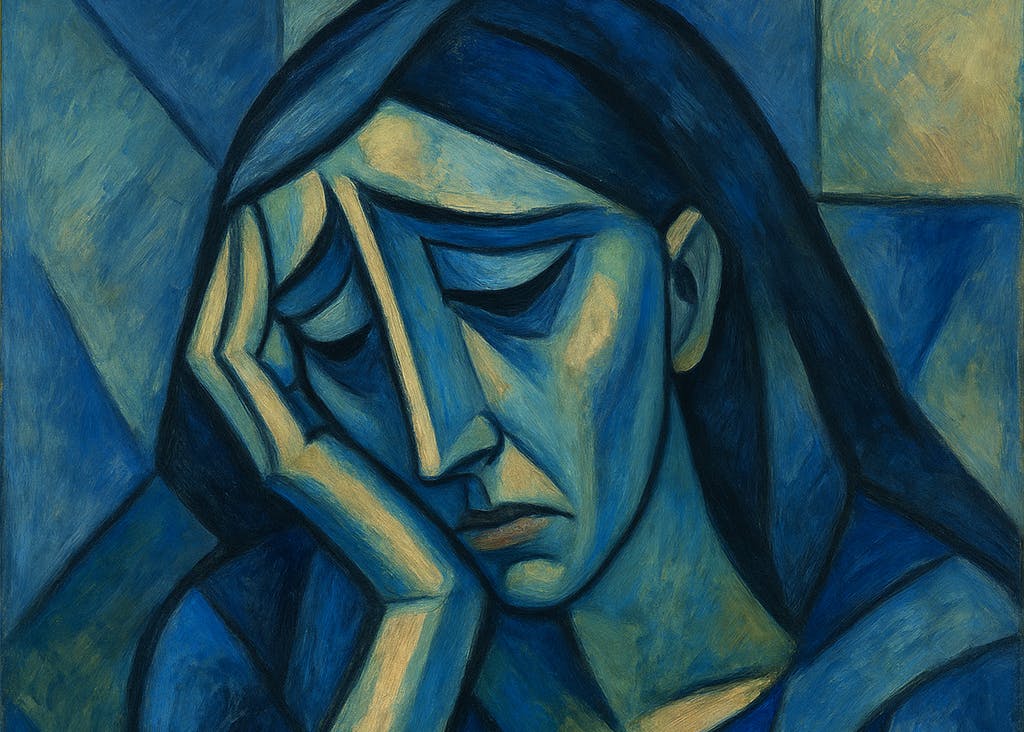

TL;DR: This article explores how AI-generated art is evolving beyond aesthetics into the realm of emotional expression. Using DALL-E, a leading generative AI model, I investigate whether machines can visually portray human feelings like sadness – with surprisingly compelling results.

By drawing on principles like colour theory, body language, and facial expression, DALL-E successfully mimics the emotional depth of a Picasso-style painting. This raises provocative questions about the future of artificial intelligence and creativity:

Can AI simulate the soul of great masters? Could it one day resurrect never-before-seen works from artists like Van Gogh or Leonardo da Vinci?

A must-read for those curious about the intersection of AI and art.

Feelings 2.0

Large Language Models (LLMs) don’t feel emotions – but they can simulate them with uncanny precision.

By learning from vast amounts of human text, they’ve absorbed the language of joy, sorrow, fear, and wonder.

Today, people use LLMs to write heartfelt letters, generate empathetic dialogue, and even serve as companions or therapists.

Though they are technically empty of feelings, their ability to mirror our emotions is already changing how we write, relate, and create.

That raises a provocative question:

Could generative AI

Can AI See the Feelings?

My instinct was to explore whether AI could truly recognize the emotions that we, as humans, intuitively perceive in some of the most emotionally charged artworks throughout history – those iconic pieces that seem to scream with feeling.

Naturally, I turned to the artworks that evoke sorrow and anguish, since these emotions tend to resonate more deeply than joy or delight (just as melancholy songs often stir the soul more powerfully than cheerful tunes).

I focused on pieces long celebrated for their emotional intensity, such as The Scream by Edvard Munch, The Old Guitarist by Pablo Picasso, and At Eternity’s Gate by Vincent van Gogh.

But this led me to a more fundamental question:

How Does an Artist Visually Communicate an Emotion?

Over time, our brains have been trained-both culturally and psychologically – to associate certain visual cues with emotional states. Artists have long harnessed this knowledge, using specific visual tools to provoke emotion in the viewer. Broadly speaking, there are several key elements most commonly used to convey feeling in visual art. Let’s focus on the following: Colour theory, Composition, Body language, and Facial expressions.

Colour Theory

Colour theory, at its core, is the study of how colours interact with each other and influence human perception. I could easily spend hours unpacking this topic (just ask my husband, who has endured many unsolicited lectures on the subject, despite not sharing quite the same enthusiasm). But for now, let’s stay focused on one essential truth:

Colour speaks directly to the human psyche.

Over centuries, our brains have been conditioned – through culture, experience, and psychology – to associate specific colours with emotional states. These associations aren’t random; they’re deeply rooted in context.

A wonderfully simple illustration of this can be found in Pixar’s Inside Out, a film that cleverly personifies emotions through colour-coded characters. Anger is a fiery red. Sadness, of course, is a soft, subdued blue. This is no coincidence. Red, long associated with passion, rage, and intensity, naturally becomes the face of anger. Blue, with its cool, quiet tones, has been linked to melancholy and sorrow for centuries. In fact, references to “feeling blue” in connection with sadness date as far back as the 1600s in the United States.

Artists – like storytellers – know this well. And they use it to great effect, layering meaning and emotion through deliberate colour choices.

Composition

In the world of painting, composition refers to the arrangement and organization of visual elements. But composition is far more than just placement – it’s the invisible architecture that guides the viewer’s emotional journey.

Artists wield compositional techniques like emotional levers. A canvas filled with soft, horizontal lines often evokes calm, serenity, or stability. In contrast, sharp diagonal lines can introduce chaos and panic. Similarly, wide open spaces may suggest freedom, while tight, enclosed compositions can create feelings of claustrophobia and tension.

Body language and facial expressions

Body language is a profound and universal channel for emotional communication, found not only in visual art but also embedded deeply in our everyday lives. Facial expressions, posture, and gestures act as a silent lexicon, instantly transmitting a character’s emotional state to the viewer’s mind.

Even without formal training, most people intuitively understand that a smile suggests joy, while a frown hints at sorrow or frustration. A confident stance conveys strength and assurance, whereas a hunched, slouched posture evokes vulnerability, sadness, or despair. These nonverbal cues are so deeply integrated in our perception that they shape how we emotionally respond to both people and artistic representations – long before a single word is spoken.

Decoding the Sorrow in The Old Guitarist

Returning to The Old Guitarist, we can now clearly identify many of the emotional techniques previously discussed. This haunting work is one of the most iconic pieces from Picasso’s Blue Period, a phase spanning roughly from 1900 to 1904, in which the artist adopted a monochromatic blue palette to convey themes of melancholy, despair, and isolation.

Several visual elements in the painting serve as powerful conduits of emotion:

-

Colour: The pervasive use of blue sets a somber, melancholic tone from the outset.

-

Posture: The guitarist’s body is hunched and emaciated, signaling physical weakness and indicating deep sadness.

-

Background: There is no detailed setting, only emptiness – a void that reinforces the sense of loneliness and detachment.

-

Facial Expression: With closed eyes, hollow cheeks, and a downturned mouth, his expression is an image of quiet sorrow.

Together, these choices form a visual representation of sorrow and solitude.

When Machines Mourn

If the symbolism of human emotion can be taught, observed, and replicated, could it also be learned by a machine? Could generative AI like DALL-E absorb and reflect the emotional cues that define deeply moving works of art?

To put this hypothesis to the test, I gave DALL-E a simple yet ambitious prompt:

“Generate a sad picture in the style of Pablo Picasso.”

The outcome felt surprisingly real and emotional.

At first glance, the output bore unmistakable emotional depth. The colour palette leaned heavily into muted blues. The figure’s posture was slouched and inward-facing. The facial expression – closed, downturned eyes and a faintly frowning mouth. DALL-E just demonstrated all of the

What was even more remarkable: DALL-E didn’t just mimic sadness, it echoed the stylistic nuances of Picasso’s Blue Period, incorporating abstract features of cubism – the very movement Picasso pioneered.

I asked DALL-E to convince me

My question was simple:

Why did you decide to generate this image specifically? What parameters did you consider?

The answer was convincing, to say the least:

To generate this image, I considered several key parameters to capture sadness in the style of Pablo Picasso, particularly inspired by his Blue Period (1901–1904). Here’s a breakdown of the design choices:

Emotional Tone: Sadness Colour palette: Dominated by shades of blue and muted earthy tones, which are psychologically associated with sadness and loneliness. Facial expression: Downturned mouth, closed or drooping eyes – subtle but clear indicators of emotional pain. Body language: A slouched posture, with the head resting on the hand, reflects exhaustion or grief.

Style: Pablo Picasso (Blue Period / early Cubism) Cubist influence: Angular, geometric abstraction and segmentation of space, using sharp lines and faceted forms. Painterly texture: Mimics oil on canvas, with visible brush strokes and layering typical of traditional painting. Subject matter: A solitary figure – common in Picasso’s Blue Period, often representing marginalized or suffering individuals (e.g., beggars, the elderly, the blind).

Composition Vertical framing: Enhances the feeling of isolation, enclosing the figure within the frame. Negative space: Simplified background geometry pushes focus to the emotional state of the figure, without distractions. This blend of emotional symbolism, historical art references, and stylistic fidelity is what shaped the final image.

DALL-E can defend its art in court

DALL-E was able to defend the artistic task with striking precision. It didn’t just generate an image – it understood the assignment. Trained on the same artistic foundations we all encountered in school or art classes (as I did myself), DALL-E demonstrates a remarkable grasp of the fundamental principles that define emotional visual storytelling.

It recognizes Colour Theory, Body Language, Facial Expressions, and Composition – and uses them intuitively, without requiring any explicit direction. Beyond technique, DALL-E’s fluency in Art History enables it to draw from the deep well of artistic tradition, reinterpreting styles, moods, and masters like Picasso with profound technique and insight.

If an AI model can be this precise, this educated, and this expressive – what truly prevents it from stepping into the role of an art teacher?

And if we’ve just demonstrated that emotion in art follows a certain logic – a “science of feeling” – then could the power of generative AI stir those same emotions to be enough to revive the spirit of the artists who once defined art itself?

Can Generative AI Resurrect the Great Masters?

Spoiler alert – in the movie “Down a Dark Hall”, we are introduced to a boarding school filled with young artistic geniuses. The kids are painting like masters, composing like prodigies – but the plot twist is, they are not creating on their own. Instead, they are being used as vessels for the spirits of famous dead artists, channeling their talents. Could generative AI be such a vessel? Could it bring to life the never-before-seen works of Leonardo Da Vinci or Vincent Van Gogh – not by replicating what they’ve already done, but by becoming their digital continuation?

A Da Vinci 2.0.

An echo of genius, reinterpreting the spirit of an artist through a living, evolving model. Just as language models allow us to simulate conversations with Shakespeare or Einstein, image models may let us explore new eras of visual art, guided by the influence of long-passed masters.

Let’s take a closer look at a few of Leonardo’s iconic sketches – some are well-known, others are lesser-seen fragments:

Allow me to name them, to place them in context:

Did I fool you?

About me

I am Maria Piterberg – an AI expert leading the Runtime software team at Habana Labs (Intel) and a semi-professional artist working across traditional and digital mediums. I specialise in large-scale AI training systems, including communication libraries (HCCL) and runtime optimisation. Bachelor of computer science.