In 2023, Hermann Hauser, the co-founder of London-based Amadeus Capital Partners, was added to a WhatsApp group packed with billionaire US investors, including Mark Andreesen and Michael Dell.

“One of the first things they did, when they invited me to join the group, was lament the fact that Europe doesn’t have any hundred-billion tech companies,” Hauser tells me.

“Well, watch Arm,” he replied.

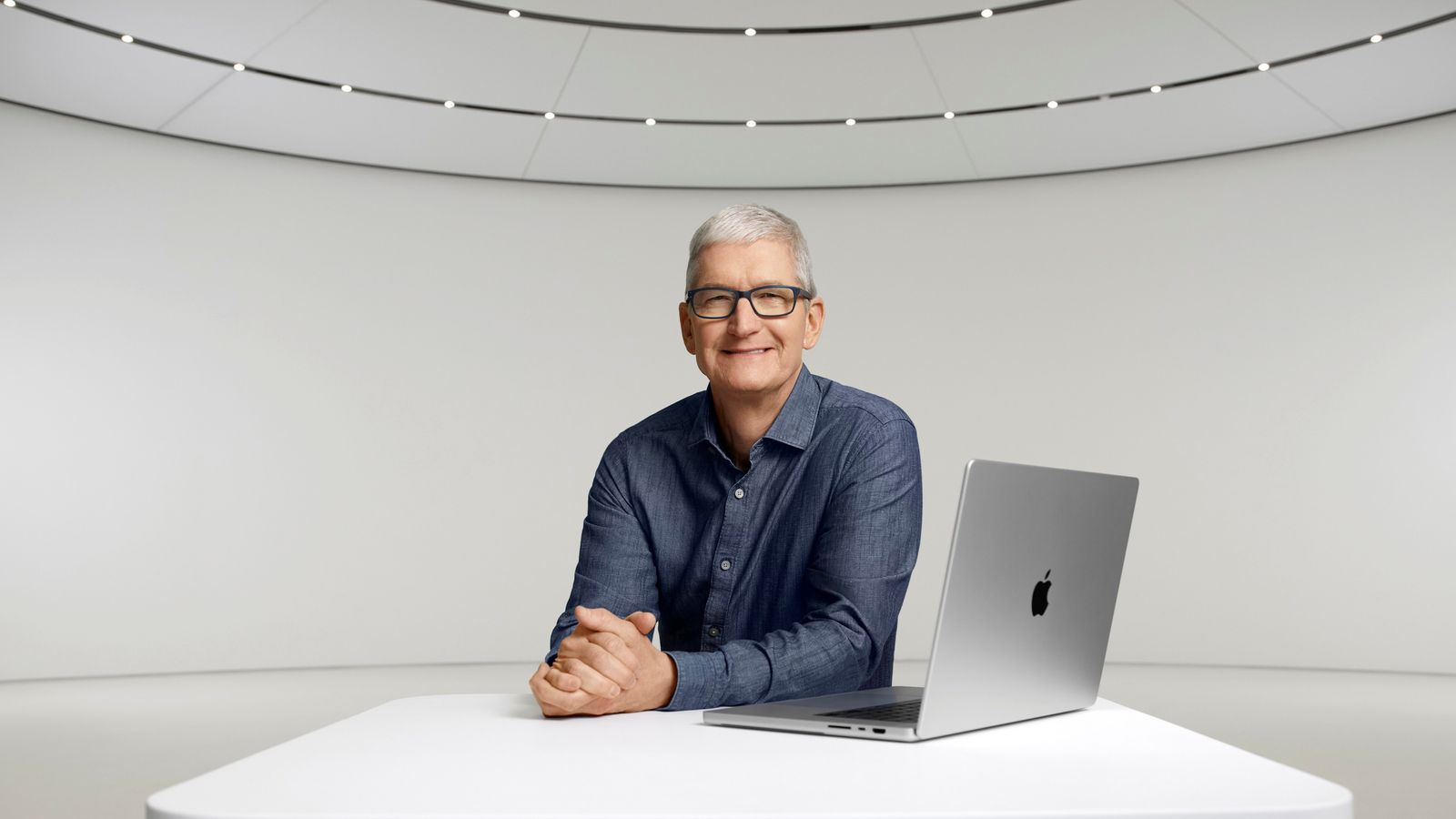

It was a good tip. A few months later, following Arm’s spectacular Nasdaq listing, the chip designer’s market cap rocketed past the $100bn mark – the first British tech firm to hit the milestone. It was a proud moment for Hauser, who had spearheaded spinning the business out of Cambridge-based Acorn Computers in the early nineties, following a small investment from Apple.

And the stock continues its remarkable ascent. It now hovers around the $150bn mark, more than double the value at its 2023 IPO, and even briefly crossed the $200bn threshold in July last year.

“I can definitely see us going way above our current valuation over the years because the demand is really there,” said Arm’s Chief Architect Richard Grisenthwaite, the firm’s de facto CTO, adding he insisted on walking on stage to the tune of Bachman–Turner Overdrive’s “You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet” when giving a speech at a recent staff conference.

“It’s in the data centres, it’s in the fact that everyone is going to be using more and more computing in everything they do. Artificial Intelligence will be part of this whole connected world we’re living in and that has tremendous opportunities for us.

“We’re seeing the demand for computing really explode…the sky really is the limit here.”

Arm’s recent financial disclosures would suggest Grisenthwaite’s bullishness is warranted.

The company is projected to hit around $4bn in turnover by the end of its current financial year in April, nearly double what it managed only three years ago. Since that time Arm has added more than 2,000 to its staff headcount to a total of some 8,000, of which the lion’s share remain in Cambridge, where the company is in the course of expanding its headquarters with a new building.

Arm has also built up a major presence in the AI industry, benefiting from its unquenchable thirst for more and more compute, in signs there is much more growth to come.

Last year, Meta announced the optimization of its Llama 3.2 large language model for Arm CPUs, Google unveiled its first custom Arm-based CPUs, the Axion Processors, and Microsoft — which this week said it planned to spend another $80bn on AI data centres – has begun using Azure Cobalt 100-based Virtual Machines, which run on a 64-bit Arm-based CPU. Last but not least, the transformative new Grace Blackwell superchips built by Nvidia – the world’s $3.5tn chip company whose shares have surged in the wake of the AI boom – will also integrate Arm CPUs.

All of those successes, and more in areas like the automotive industry, Internet of Things devices and the backbone of Arm’s business, the smartphone processor architecture, have propelled the company into the ranks of the most valuable semiconductor businesses on the planet.

Arm is now within touching distance of exceeding the market caps of US giants Qualcomm ($175bn) and Texas Instruments ($173bn) and it has already surpassed the likes of Applied Materials ($138bn), Micron ($100bn), and most pointedly, its arch-rival and founder of the X-86 instruction set, Intel, which over the past year has seen its value more than halve to $88bn.

“When I started out, attracting someone out of Intel, just as an employee was ‘wow what a coup, we’ve got that guy’ – nowadays we can really afford to be quite picky,” Grisenthwaite said, with a twinkle in his eye.

Arm’s rivalry with Intel stretches back decades to a terse exchange between the California-based business and Hermann Hauser in the late 1980s.

“ I approached Intel and asked them to modify the 8086 [microprocessor], so that we could use better pins,” Hauser said. “They had both the data bus and the address bus on the same pin and we needed them on separate pins.

“And they said, ‘who the hell are you, get lost!’

“We were riding high at the time…so arrogantly we said: ‘Well, you get lost, we’ll do our own!’”

“If they had modified the 8086, we would have never started with the Arm so it is ironic that Arm is now worth twice as much as Intel.”

Arm is now of such a size that it even reportedly made an offer to acquire a chunk of Intel late last year – an offer than was ultimately rebuffed. Had it gone through, it would not be the first part of Intel that Arm had acquired, after it bought a site in Chandler in Arizona when Intel divested it several years ago.

But it’s easy to forget that at a time when Intel was already a huge US business in the early nineties, Arm was starting out with just a dozen staff, based out of a barn in Cambridge. How did it catch up?

“We really owe this to Robin Saxby, the first CEO we brought in,” Hauser said.

Derbyshire-born Saxby had been working out in California at Motorola Semiconductors, his employer for more than a decade, when a recruiter called asking if he’d like to run a British chip startup backed by Apple. He was quick to set his preconditions for the job.

“I said in the interview, ‘the only way we’re going to make this work is if we make this a global standard.’”

“It was a mad statement to make when they moved into the Arm barn with twelve people and two customers,” said Hauser, but Saxby stands by it.

“I was aware of the American, the Japanese and the European semiconductor market. Everyone was spending a fortune designing their own microprocessors,” Saxby said.

“If you were the market leader, your return on investment designing those chips is a good idea, but the ones who lose are just wasting a lot of money on R&D.

“Customer pull is a thousand times more important than technology push. If you solve a real problem for customers, you’ll get a purchase order, but if you try and push the technology that might be great at university that nobody wants, you’re not going to get a business.”

Saxby’s strategy paid off, thanks in part to some early customer wins with Nokia and Nintendo (the architecture is still used in its Switch console today).

But the really big win came in 2006, when founding investor Apple approached Arm to design the microprocessor for this new device it was working on called the iPhone. That partnership flung the doors open to the smartphone market for Arm, whose architecture is now used in nearly every phone on the planet.

Apple had first approached Intel for help designing the chip, but they weren’t interested. And in 2020, Apple announced it would move all its computers away from Intel chips in favour of its own Apple Silicon designs, all of which use the Arm architecture.

Saxby’s ruthless determination remains embedded within Arm’s culture. But despite the firm’s seemingly unstoppable momentum, several obstacles lie in the way of further growth in 2025.

For a start, the company appears to be seeing a gradual decline in the number of chip shipments. In May 2023, Arm posted a 10% fall in the number of chips shipped in its fourth quarter compared to the previous year. The following July, the company stopped publishing chip shipment figures altogether, putting the move down to a “shift” towards “higher-value, lower-volume markets.”

Arm also lost a protracted – and likely costly – legal dispute with Qualcomm earlier this week, in which it had demanded the renegotiation of a licencing agreement following the latter’s acquisition of ex-Arm customer NUVIA in 2021.

There is also the steady drumbeat of concerns that the world’s frontier AI companies are running out of steam — that the available sources of data on which to train generative AI models are growing thin, causing the gap between new releases of models to widen. When the data runs out, will more data centres really be needed?

“Sometimes people talk about bubbles,” said Jake Silverman, a semiconductor analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence.

“Semiconductors always go through a cycle. At some point there will be a slowdown in spend [but] whether that’s in two years or ten years is unclear.

“I would suspect that the hyperscalers are very focused on making sure they’re able to monetise AI and unless they hit a wall in terms of their ability to continue monetising and growing that monetisation, they’ll continue to invest in it.

“Could that change rapidly? Yes it can always change rapidly. Could there be a build-up of inventory at some point? At some point there probably will be. But it seems like it’s not going to happen at least in the next year.”

But even if there is no AI bubble – or at least, it doesn’t burst any time soon – that does not guarantee Arm’s business in perpetuity. A major alternative architecture has emerged over the past decade known as Risc-V – an open-source, royalty-free instruction set that offers a cheaper, more customisable option over Arm.

Ever the supporter of open-source technology, Meta has been one of the best-known adopters of Risc-V over the past couple of years. And, says Silverman, Risc-V is likely to be “more of a priority” for China, after the stifling effect that restrictions on US chip exports had on the growth of some of its biggest tech firms (in 2019, Risc-V even moved its headquarters from the US to Switzerland, a geopolitically neutral new home).

Throw into the mix the Trumpian erection of fresh tariffs and protectionist measures across the US, Europe and China, and Arm, with its customer base spread across so many different markets, appears caught in a legal and regulatory quagmire.

But Grisenthwaite appears sanguine about the trade and geopolitical challenges that lie ahead, insisting that Arm is able to do design work in different markets in order to meet varying export rules. “Exploiting differences where they exist is a perfectly sensible thing to do,” he said, adding that Arm is well-versed in getting itself heard at the negotiating table, including in 2022, when the US introduced restrictions to stop high performance AI training systems being exported to China.

“The way they worded those original rules actually created a whole bunch of effects on much more ordinary commercial servers or the ability for us or other companies to provide technologies for that which wasn’t the goal in the slightest from the US point of view,” Grisenthwaite said.

“We spent quite a lot of time talking with officials to help them refine the rules and a year later they came out with rules which were actually much better targeted and avoided the collateral damage.”

Arm has also circumnavigated geopolitical issues in China through the creation of a Chinese subsidiary in which it holds a 49% stake. But that has not been without its own challenges, among others the refusal of the Chinese CEO to resign when Arm asked him to step down (he eventually quit and founded a Risc-V startup).

Back in Cambridge, a lingering question remains in whether Arm will retain its British identity despite an ever-growing presence in the US.

Hermann Hauser was among the most vocal critics when Arm was yanked off the London Stock Exchange in 2016 after being taken private by Masayoshi Son, the boss of Japanese investor SoftBank, in a £24bn deal. But Hauser now acknowledges that Son, who remains chairman of Arm, has been a good custodian of the business, fulfilling his pledge of keeping the company’s headquarters in Cambridge.

“When I originally talked to Masa Son many years back, he said ‘I promise I’ll look after your company’ and he did,” Hauser said.

SoftBank’s recent acquisition of struggling Bristol-based chipmaker Graphcore also completes Son’s promise of expanding Arm into a third British city after Cambridge and Manchester, a move which entrenches Arm’s UK presence and broadens its expertise.

But it still irks Arm’s founding members that the company has so far failed to arrange a secondary listing on the London Stock Exchange. At the time of its first IPO in 1998, Arm had a listing in both London and New York, but despite the best efforts of British politicians in 2023, no dual listing materialised this time round.

As recently as October, Arm CEO Rene Haas said the company was “still open” to joining the London Stock Exchange, but that the move was “not top of mind right now.”

“I’ve given up on the idea that Arm will get a listing in London,” Hauser said.

“The actual country in which you’re listed is not really connected with the operations, these are orthogonal problems. But that does not mean that there isn’t a drift towards California because Rene spends most of his time in California.”

Grisenthwaite insists that, despite the Nasdaq listing, Arm’s operational centre of gravity remains in Cambridge, where most of the senior engineers are based, and that the company retains its British identity.

“It has some very British characteristics which slightly confuse our American colleagues,” he said.

“It also has some American characteristics that confuse our British colleagues. And our French colleagues are confused by both.”