Domain-Driven Design (DDD) can upskill sociotechnical design to navigate organizational dynamics and decision complexity in human systems, Xin Yao explained at OOP Conference. She presented how change smuggling offers a practical way to launch small, safe-to-fail probes, nudging sociotechnical changes to emerge organically and conversationally.

Today’s software professionals navigate a maze of technical, business, and social complexity. According to Xin Yao, thriving in this environment requires more than technical and business expertise, and sociotechnical design helps us deal with these challenges.

Sociotechnical design in software development emphasizes creating systems where people and technology thrive by fostering collaboration, emergent coherence, and shared understanding through enabling constraints. As a result, sociotechnical design can improve architectural decisions, Xin Yao explained.

DDD is a sociotechnical practice, Yao explained:

It’s hands-on and grounded in the idea that software design must align with business complexity, which ultimately means aligning with people: users, customers, domain experts, etc. DDD bridges technical models and human understanding, ensuring software closely reflects the mental models and workflows of the business. DDD’s context mapping patterns reveal team boundaries, collaboration modes, and the subtle interplay between human organization and code organization.

DDD treats organizational complexity as a means to a technical end: keeping the software model coherent and maintainable. Sociotechnical design takes the next step: it treats organizational and human system dynamics as first-class design material, Yao said. Where DDD models business complexity for better software, sociotechnical design models organizational complexity for better work. DDD aligns software with the domain, sociotechnical design coheres and complexifies software, teams, and organizations into a living, evolving system, Yao mentioned.

Large-scale change initiatives often fail because they trigger resistance: decisions are imposed from above, and the messy reality of human systems gets oversimplified, Yao said. Change smuggling gives software practitioners a gentler, safer way to introduce sociotechnical thinking when formal channels feel unnavigable or blocked. Instead of pushing for change among peers or upwards, change smugglers embed small, safe-to-fail experiments – Trojan Mice-inside existing structures. Rather than saying the organization is too slow to change, Yao explained, we can explore what’s possible from a learning-together stance.

Change smugglers form authentic partnerships. They create spaces where doubts and possibilities can coexist, favor peer connection over positional influence, and seed local shifts in how people work together – without setting off the corporate immune system, Yao explained:

For example, instead of forcing teams into a new collaboration model, a smuggler – previously known as change agent – might unceremoniously reframe an existing meeting into a participatory modeling session, subtly reshaping decision-making dynamics.

To level up, software professionals need to go beyond technical excellence: insist on understanding the whole picture, shape information flow, design collaboration, model experiential coherence, and see uncertainty as an ally, Yao concluded.

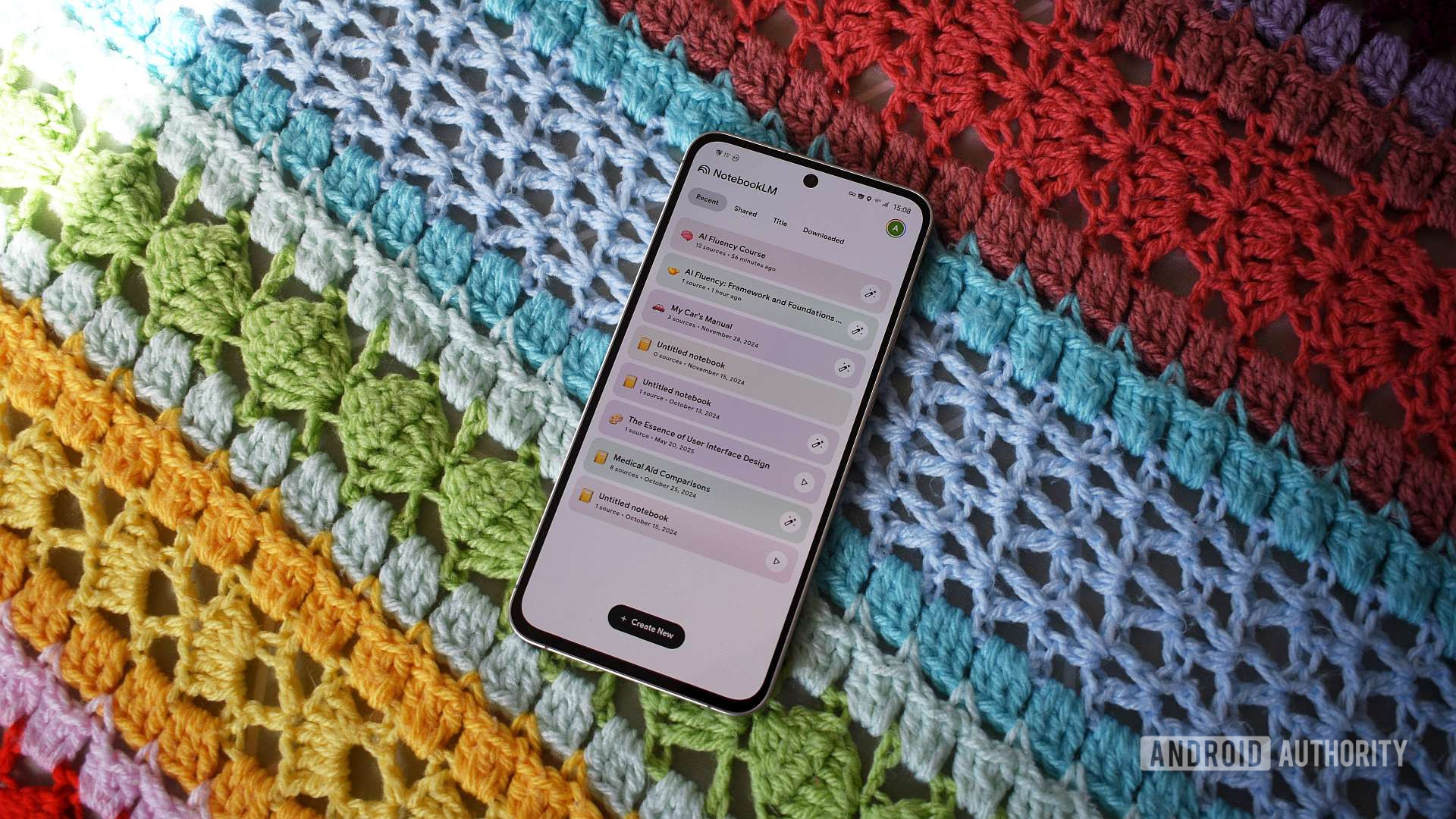

InfoQ interviewed Xin Yao about DDD and change smuggling.

InfoQ: How can DDD practitioners and software architects become skilled sociotechnical designers and architects?

Xin Yao: If you’re great at DDD, you already think beyond code – you model the business, engage with domain experts, and shape software around real-world complexity.

Now, take that mindset and zoom out. Think of it like career progression:

- Junior DDD: “How do I design better aggregates and value objects?”

- Mid-level DDD: “How do teams collaborate to model Ubiquitous Language within Bounded Contexts?”

- Sociotechnical designer: “How do team co-design and co-evolve software and human systems using relational methods and sociotechnical architecture?”

InfoQ: What can they do to upgrade their toolbox?

Yao: Some of the tools that they can add to their kit are:

- Context Mapping – probe social and technical boundaries. Where do friction and dependencies really come from?

- Experience Design for Coherence – creating lived, collaborative experiences that foster deep conversations, sense-making, and shared agency over their work.

- Sociotechnical Architecture – defining quality attributes for the social architecture, such as connection, belonging, and aliveness, and modeling them with discipline.

- Leader as Convener and Connector – Shifting from architect to conversation catalyst, offering in-context support so teams can find their own way.

- Appreciating uncertainty – treating the unknown as creative fuel. The best designs emerge at the sweet spot between structure and improvisation, guidance and freedom, stability and variation. Think of it like sailing—you can’t control the wind, but you can adjust the sails.

The next time they hit an architecture crossroad, they can ask themselves: is this a tech problem, or is it also shaped by social complexity? Then, design for both. That’s the upgrade.

InfoQ: What makes “change smuggling” an effective approach to sociotechnical change?

Yao: Because it works with, not against, a social system’s natural dynamics. Small experiments shift interactions and sociotechnical learning without threatening identity or power. Over time, these enabling constraints bring about constitutive constraints – patterns of interaction that shape the system. Eventually, they evolve into governing constraints, shifting how work happens at scale.

It’s less storming the castle, more sneaking in through the kitchen and winning hearts one conversation at a time. Effective sociotechnical change isn’t about declaring war on the status quo – it’s about redesigning the conditions for self-sustaining changes to emerge.