When Sullivan Emerald began his secondary education in Nekede, a quiet rural community near Owerri, his future ambitions were framed by stories his father read aloud from local newspapers—tales of brilliant Nigerian engineers who had made it big in the oil and gas industry. Inspired, Emerald aspired to study petroleum engineering. But after multiple failed attempts to secure admission into his desired course at the Federal Polytechnic Nekede, he reluctantly opted for computer science. That reluctant detour, however, turned out to be a revelation. It sparked an interest in programming and a passion for software development that would align him with a bigger vision: positioning Imo State at the forefront of Nigeria’s artificial intelligence (AI) push.

Now a budding software engineer at Adminting, an ad-tech startup operating from the Imo Digital City, Emerald is part of a generation of young Imolites riding a new wave: AI. For these young people, Imo’s ambition to become Nigeria’s AI capital is a chance to compete globally without ever leaving home.

A digital uprising in the heart of the southeast

Geographically, Imo State is compact but vibrant, tucked in Nigeria’s southeast and surrounded by Anambra, Abia, Rivers, and Delta states. It boasts lush greenery, rich red soil, and an interwoven network of rivers and streams that sustain its largely agricultural communities.

Imo State’s literacy rate has shown a steady upward trend, rising from 80.8% in 2010 to 92.1% in 2023, and is projected to hit 96.43% by 2025, making it the leading state in general and youth literacy in Nigeria. This progress is largely credited to a comprehensive free education policy introduced in May 2011 by former Governor Rochas Okorocha.

“Governor Okorocha reawakened the minds of Imo people through his free education policy,” said Kelechi Ugo, a journalist based in the state. “His initiative, which covered education from basic through tertiary levels, was a game-changer.”

However, the foundation for this policy was laid by Okorocha’s predecessor, Governor Ikedi Ohakim, who had earlier ordered the implementation of free education across all levels. Ohakim also spearheaded the return of some schools to missionary organisations to enhance management and improve educational outcomes.

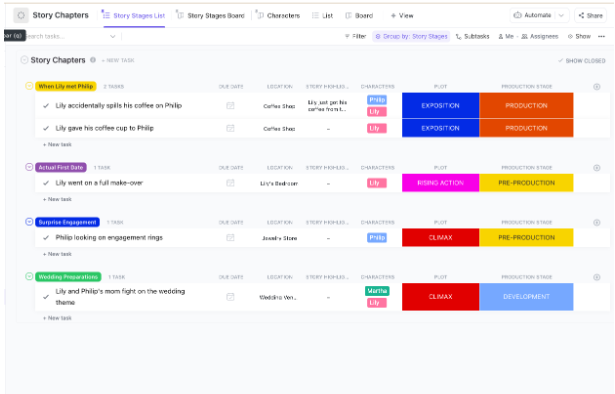

That strong educational foundation now forms the bedrock of the state’s tech renaissance. At the centre of this digital evolution is the Ministry of Digital Economy and E-Government, created in 2022 under Governor Hope Uzodinma. The ministry’s flagship agenda, known as IDEA 2022–2026, aims to train 300,000 Imo youth in high-demand skills, including AI, data analytics, machine learning, and cloud computing.

“In Imo, the idea of literacy has changed,” said Chimezie Amadi, the state’s Commissioner for Digital Economy and E-Government. “It’s no longer about reading and writing, it’s about using digital tools to solve real problems.”

The Imo State government says it has trained over 40,000 people through its Skillup Imo program, equipping them with digital and AI skills. The program has already produced two cohorts—5,000 graduates in the first and 15,000 in the second. About 150 of these graduates have gone on to secure remote freelance jobs, launch their startups, or actively contribute to the expanding tech ecosystem within the state, according to Primus Amaefule, the project manager of Imo Digital City.

Training activities are centered at the Imo Digital City in Owerri, which serves as a dynamic hub for boot camps, coding workshops, and AI education, including programs for primary and secondary school students. The state has partnered with international tech firms, including Cisco, Huawei, and Zinox, to provide technical expertise. Meanwhile, local companies like Frankbotics and other tech hubs, primarily located in Owerri, help identify and train participants from schools within the communities.

The state’s AI drive extends beyond students: farmers are learning how to use generative AI to boost yields; health workers are being onboarded onto new electronic medical record systems powered by AI; and state databases are being overhauled to support data-driven governance.

Perhaps most ambitious is the effort to build Nigeria’s first sub-national AI research centre in Imo’s Digital City. “We’re collecting biometric data of all our farmers,” Amadi explains, “so we can train AI models to recommend the best crops per region, detect pest patterns, and guide support policies.”

The state is also collecting land data to automate land services end-to-end across the state through the Land Information Services Centre, according to Primus Amefule.

“They had special GIS training so that they could do land administration in Imo State. So if you want to register your land, it is already digitised,” said Amaefule. “We also have a mandate to develop websites for all the ministries in the state

International partners—including Ericsson, UNDP, and the EU’s Digital SME Alliance are already providing technical support to the program. Some have even signed talent exchange programs and startup accelerator deals.

But for all the momentum, a pressing question looms: Can this digital vision survive the turbulence of insecurity gripping the state?

A crown under siege

While the Imo State government aspires to brand the state as Nigeria’s innovation hub, the reality on the ground often paints a far more troubling picture.

Between 2020 and 2025, insecurity in Imo State has resulted in significant loss of lives and widespread fear. Over 650 people were killed due to criminal violence, including attacks by separatist groups, criminal gangs, and gunmen from January 2020 to May 2024. Notable incidents include the killing of at least 30 travelers in a single attack along the Okigwe-Owerri highway in May 2025. The violence has also targeted clergy and religious personnel, with more than 50 victims recorded between 2015 and 2025. Mass graves have been discovered in areas like Orsu LGA, where over 200 human remains were found, highlighting the scale of killings and the profound impact on local communities.

The financial burden of insecurity is equally severe, particularly in terms of ransom payments for kidnappings. From July 2023 to June 2024, Imo State paid a total of ₦39 million ($25,467) in ransom to kidnappers, which was 390% higher than the initial demands, according to SBM Intelligence. In the same period, there were 15 reported kidnapping incidents in the state, with 30 people abducted. The Southeast region, including Imo, led the nation in ransom payments, with a total of ₦419.2 million ($273,738) paid, accounting for 40% of the nation’s total.

The persistent insecurity has led to a heavy joint military presence characterised by roadblocks on many roads that impede human and vehicular movements within Owerri and other communities. The fear of “Unknown gunmen” keeps many techies in Imo State constantly looking over their shoulders and ready to run at the sound of a gunshot.

“As someone in tech, have I thought of leaving Owerri due to the consequences of insecurity? Yes, every day of my life,” said Emerald. “I have seen people who have the privilege of moving to a city like Lagos making waves and generating a good life for themselves. Yes, if I have the opportunity, I will leave Nigeria without regretting it.”

This tension—between an aspirational tech hub and a fraught security environment—could be Imo’s biggest challenge. As much as AI promises productivity, precision, and prosperity, it requires one foundational ingredient: stability.

A fragile infrastructure

That need for stability is also central to attracting long-term investment. Frankbotics, the Owerri-based company behind the state’s pilot precision agriculture tools, has tested its technology in six local government areas and even presented it to EU representatives. But without funding, further development remains stalled.

“We’ve gone past the ideation stage,” said Frankbotics founder and CEO Frank Uchehara. “We have a working prototype. What we need now is the investment to scale it.”

But investors remain wary.

“In Imo, there’s almost no real interest from private firms,” Emerald said. “Insecurity makes a place unattractive, no matter how strategic its location.”

Prisca Amaefule, CEO of Adminting, said the company has relied on founders’ investments and early revenues. However, she admits that raising venture capital for a tech company in Owerri is not a walk in the park due to the limited local investor networks.

“Most VCs and angel investors gravitate toward Lagos or Abuja, so pitch meetings are harder to come by here in Owerri,” said Amaefule. “Most investors here are more experienced and interested in hotels, restaurants, and bars. I don’t think most of the supposed investors fully understand the tech ecosystem and how it works. But I truly believe if they were familiar with it, they would invest.”

Even with notable digital talent and ambition, Imo’s foundational tech infrastructure still lags. As of 2023, the state had 1,448 kilometers of fibre optic cable, placing it in the lower tier nationally. Most of the country’s metro fibre remains concentrated in Lagos, Ogun, and Abuja. Imo is not among the top 10 states for internet users, underscoring persistent gaps in broadband access, especially in rural and underserved communities.

Efforts are underway to close this gap. The Imo Digital Economy Agenda (IDEA) 2022–2026 outlines plans to attract investment, connect public institutions, and expand infrastructure. The state has upheld the ₦145 per metre Right-of-Way charge set by the National Economic Council and implemented a “dig-once” policy, which enables infrastructure companies to lay fibre across 3,000 kilometers using a unified fibre duct system managed by a state-approved provider. Through the Heartland Fibre Optic Company, a special-purpose vehicle (SPV), the state can connect the rural and urban communities. SPV’s fibre ducts have covered three local governments, including Owerri North, Owerri West, and Owerri East.

“Their (Heartland Fibre Optic Cable) immediate target is to cover the base stations within these three local governments with fibre and upgrade the network to either a 4G or 5G network to give us a modern communication infrastructure,” Commissioner Amadi said. IHS has secured a 15-year lease to lay fibre optic cables through the ducts already provided. MTN has also begun fibre-to-home services in Owerri.

Still, challenges persist. Telecom tower density remains moderate, and fibre cuts frequently disrupt services. In June 2025, Imo was among nine states hit by major fibre cuts, leading to widespread network outages across MTN, Airtel, 9mobile, and Globacom. The blackout affected communities in Ideato North, Owerri Municipal, and Owerri West.

“Insufficient infrastructure, including unreliable power supply, poor road networks, and limited access to quality education and healthcare, can hinder my productivity and overall well-being,” said Brandnew Emmanuel, a digital expert living in Owerri.

The groundwork for a digital economy may be in place, but without physical security and dependable infrastructure, Imo’s digital promise risks becoming a mirage.

A rural culture of innovation, digitally reimagined

Still, Imo’s pursuit of AI excellence isn’t just a top-down initiative. It’s tapping into something deeply cultural.

The rural towns of Mbaise, Okigwe, and Orlu—though more known for agriculture than algorithms—are quietly becoming micro-clusters of innovation. These communities, built around self-help and collaboration, are reinterpreting those values through tech. Informal tech meetups, coding collectives, and small developer groups are springing up, especially among unemployed graduates and NYSC members posted to the region.

The state’s road infrastructure—decent by regional standards—makes inter-town connectivity smoother, allowing digital programs and ideas to scale fast.

“When one person learns Python in Owerri,” says a Skillup Imo trainer, “they’re teaching five others in Umuaka by the end of the week.”

This communal learning structure gives Imo a unique edge. Unlike Lagos, where tech often feels elitist or corporate, in Imo, it’s more grassroots, intimate, and arguably more resilient.

Will the talent stay?

Commissioner Chimezie Amadi remains optimistic about talent retention. He argues that the state is not just training digital workers, but also building a sustainable ecosystem around them. Through partnerships with platforms like Suburban, an Abuja-based gig aggregation firm, Imo-trained developers are already securing six-figure remote contracts from U.S. clients while continuing to live in Owerri, he claims.

“Our goal is for 60% of graduates to get jobs and 40% to start businesses,” Amadi said. “Some of them are already earning ₦1–2 million monthly through remote work.”

But not everyone shares his confidence. For talents like Brandnew Emmanuel, the opportunities still fall short of what’s needed. “There just aren’t enough platforms or companies to absorb all the people graduating from these digital programs,” he said. “And that’s not even counting the millions of others who’ve left school without any job prospects.”

As of 2023, Imo’s unemployment rate stood at 10.9%, translating to over 241,000 unemployed people and placing it among the five states with the highest unemployment in Nigeria. While this marks a drop from its 2020 peak of 56.6%—largely due to changes in how the National Bureau of Statistics calculates the metric—joblessness remains especially acute among youth and university graduates.

Without a strong local private sector to absorb these skilled individuals, many are drawn to larger cities or foreign opportunities. And with insecurity on the rise, some families are encouraging their children to leave the state entirely.

“This job scarcity can lead to frustration and disillusionment,” Emmanuel added, “and eventually, people start looking for better opportunities elsewhere.”

It’s a striking paradox: Imo may lead Nigeria in literacy and digital training, but without safety, jobs, and economic opportunity, it risks exporting the very talent it works so hard to cultivate.

Too early to crown

There’s no doubt that Imo State is charting a bold path in Nigeria’s digital transformation—one that few other subnational governments have attempted. Its deliberate investments in artificial intelligence, youth-focused tech talent, data governance, and cross-sector digital infrastructure could become a model for other states seeking inclusive innovation.

Imo Digital City’s Amaefule believes there’s also value in building without the pressures that come with external funding.

“Bootstrapping from Imo has forced us to test product–market ruthlessly fit, stay lean, and validate our business model under tough constraints,” she said. “The upside is that the tech ecosystem here is energetic—it’s easier to get young people to try out new products than to convince traditional investors to bet on early-stage ideas.”

This report was produced with support from the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) and Luminate.

Mark your calendars! Moonshot by is back in Lagos on October 15–16! Join Africa’s top founders, creatives & tech leaders for 2 days of keynotes, mixers & future-forward ideas. Early bird tickets now 20% off—don’t snooze! moonshot..com