Shortly before 11:00 a.m. on November 7, 1940, an impressive American suspension bridge was minutes away from becoming engineering history. In that mass there was only one dog trapped that no one could save. A few minutes after 11, the cameras filmed one of the most shocking scenes ever recorded.

This was the story of a huge failure.

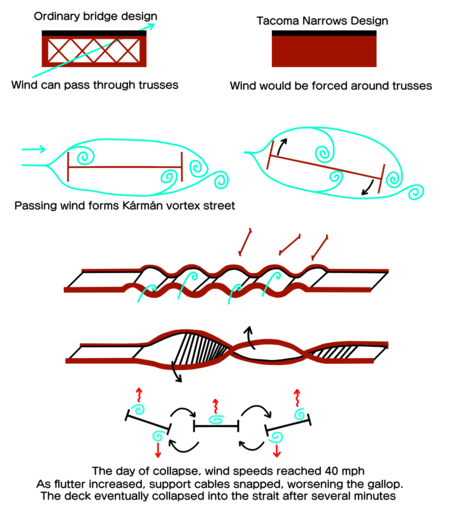

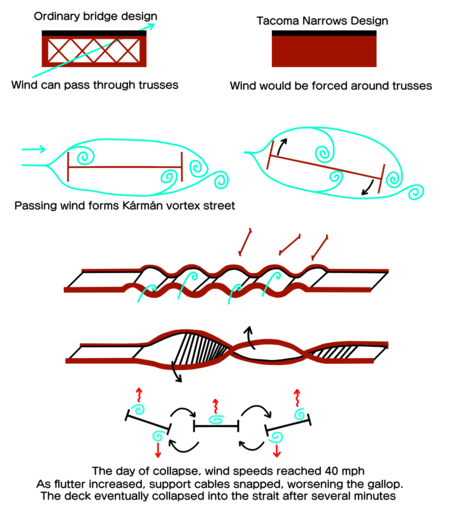

A too light masterpiece. When the Tacoma Narrows Bridge opened in July 1940, its slim, elegant silhouette was intended to symbolize a new era of economical engineering and structural efficiency. Leon Moisseiff, one of the most prestigious engineers in the country and architect of the Golden Gate, had designed a stylized colossus that, however, from day one began to show disturbing behavior: the board vibrated and waved even in moderate breezes.

Workers baptized the structure “Galloping Gertie,” a nickname as colloquial as it was revealing, because it indicated that something profound and still misunderstood was disturbing its stability.

First investigations. Teams at the University of Washington began intensive studies: scale models, wind tunnel tests and emergency solutions such as hydraulic jacks and temporary cables. Nothing managed to stop the oscillations.

The bridge, too thin, too light, too faithful to a refined aesthetic, had been pushed to the limit by the design philosophy of the Great Depression, one in which materials were reduced to the essentials and aerodynamic resistance was not yet a mature science.

The disaster. On November 7, 1940, with winds of around 65 km/h, Gertie experienced what research defined as “an abrupt transition between the usual vertical oscillations and a violent torsional movement that soon became unmanageable.” Motorists and reporters experienced scenes that seemed taken from a fantastic story: sections of the ground that disappeared underfoot, jumps in the void between undulations, and a twisting rhythm that intensified until the structure folded in on itself.

At 11:02 in the morning, the center of the bridge fell into the strait. The only victim was Tubby, a dog trapped in an abandoned car. The spectacle, filmed with chilling clarity, became one of the most influential visual documents of modern engineering.

What the hell happened. After the fall, investigations determined that the collapse was due to a phenomenon unknown in its complexity at the time: what was known as flutter torsional. When one of the suspensions gave way, the deck adopted an asymmetrical geometry that allowed the wind to feed the bridge’s torsion.

The structure was no longer agitated by the atmosphere: it was its own movement that generated the destructive force, not the wind. The “self-excited” oscillation grew without limit until it caused a total fracture. That tragedy buried the classic theory of “deflection,” which held that only vertical movements were relevant in a suspension bridge, and forced the development of new aerodynamic principles and a rigorous standard of wind tunnel testing that has since been applied around the world.

Bridge opening day in 1940

Reconstruction and correction. In the years that followed, the United States rewrote bridge engineering manuals. A more robust replacement was designed, with a wider skeleton, heavier cables and open grilles to reduce wind action. “Sturdy Gertie,” inaugurated in 1950, corrected the conceptual errors of its predecessor and became the symbol of a lesson learned through the catastrophe.

Decades later, in 2007, a new section was added to absorb the growing traffic. And while engineers built a safer bridge on the surface, the underwater world began to claim the remains of the original bridge, which lay scattered more than 200 feet beneath the waters of Puget Sound.

Collapse day

Unexpected metamorphosis. Extraordinarily, what began as an accidental shipwreck ended up becoming one of the most extensive and unique artificial reefs in the Pacific Northwest. In the depths of the strait, twisted beams and ruined metal plates became covered in anemones, sponges, algae and layers of organisms that transformed the tragedy into a hive of underwater life.

Wolf eels snaked through the knots in the steel, giant Pacific octopuses found refuge in the folds of the collapsed deck, and schools of fish prowled the rubble. For divers, it was an almost mythical landscape: a metal forest colonized by marine life, so lush that it gave rise to the legend of a gigantic “Octopus King” who, according to Tacoma residents, reigned in the shadows under the bridge. The magic of that accidental ecosystem was that nature took a vestige of human engineering and turned it into a sanctuary.

Depiction of Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collapse

Threatened legacy. However, as the decades passed, the environment changed disturbingly. Various witnesses who dived in the nineties describe an underwater garden teeming with fauna, but today, most of that splendor has disappeared. Overfishing, combined with ecological changes in the Puget Sound, has dramatically reduced the presence of iconic species.

Sea creatures and giant octopuses have migrated to less exploited areas, the fish are smaller and in many sections only the remains of hooks and gear remain. The least affected points are, paradoxically, those found under the current bridge, where fishing is complicated and marine life resists. Still, for many experts, the deterioration of the artificial reef is a reminder of the vulnerability of unintentionally created ecosystems and how human intervention (on land or sea) defines which life thrives or disappears.

History, memory and protection. The remains of Galloping Gertie were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in the 1990s, not only as evidence of a landmark of failed engineering but also as a testament to nature’s ability to transform ruins into habitats. Today some advocates aspire to an even higher status: turning the site into a marine reserve, protected against extractive activities and recognized both as ecological heritage and as a fundamental chapter in engineering history.

An extraordinary failure. If you also want, the story of the Tacoma Narrows is not only that of the collapse of a bridge, but that of a double transformation: that of engineering knowledge, which evolved as a result of the disaster, and that of the underwater ecosystem that emerged from the rubble. The collapse spurred global changes in the way large structures are designed and tested. The remains, for their part, generated a biological refuge whose conservation is urgently debated today.

Between both dimensions, technical and biological, there is an enduring lesson: human errors can be devastating, but they can also, unintentionally, sow the conditions for life to flourish in unexpected ways.

Image | Wimedia Commons

In WorldOfSoftware | China has built the highest bridge in the world and has done what it must: turn it into a show

In WorldOfSoftware | 96 trucks for five days, the critical test that the new highest bridge in the world has passed. It’s in China, of course.