Each person has their own Roman Empire. This is those five minutes a day that we dedicate to thinking about what we are passionate about, and issues such as mega -structures or absurdly large tractors can be that personal “Roman Empire.” Speaking of huge machinery, we have the tunneladoras. They are getting bigger and have more technology, but they are not advancing to the rhythm that, perhaps, we would need to transform the cities.

Because after a few meteoric years, its speed seems to have stagnated. And … makes sense.

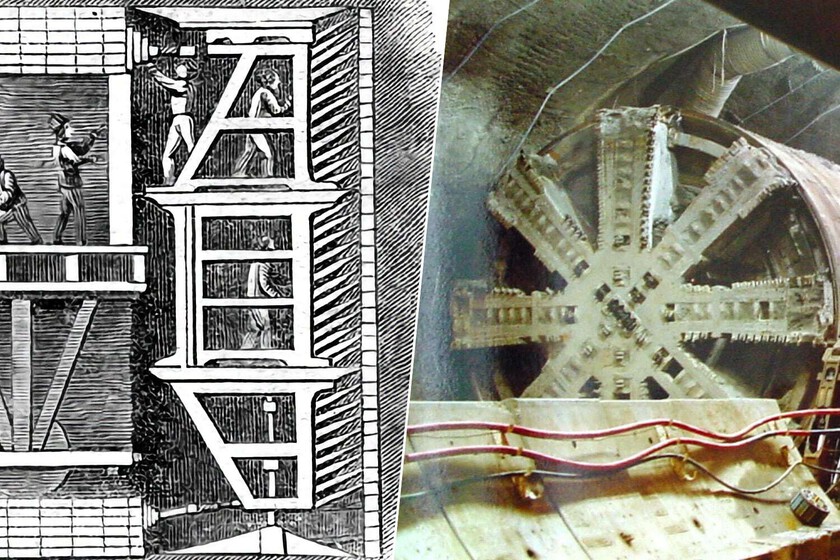

Desperately slow beginning. The history of the tunneladoras is relatively recent, since it is a machinery that depended on the technological advances in machinery. Inspired by the cranial shell of Los Teredos, which are mollusks with jaws capable of drilling the wood of the ships, the French engineer Marc Isambard Brunel patented in 1818 the tunnel shield. It was a revolution and, literally, a shield: it was a cast iron structure that protected the miners while they chopped.

As they progressed, the finished section was reinforced with bricks and advanced the shield by huge cats. It was still a manual work, but going protected with that shield and not “discovered” allowed to undertake works as complex as that of the tunnel under the Thames. And the problem is that this prototumer advanced to the rhythm of the work of the workers: one meter a day, more or less.

Brunel’s shield. On the right side we see the operators picing and advance the shield from the rear while, from behind, another group is responsible for placing the supports

Electricity does not improve things. In the development of the tunneladoras there were three key moments. The first was the idea of the shield, the second the mechanization of the tool. Throughout the nineteenth and early 20th century, different engineers tried to improve Brunel’s formula by adding cutting devices to the shield’s head.

Several ideas such as drills and cutting discs were tested that were mounted in their arms or on a frontal rotating plate. This mechanization was achieved thanks to pneumatic systems, steamed and, subsequently, electricity. It was clear that they were safer for operators thanks to that automation, but the drilling rate, although it had bent with respect to the manual rhythm, remained slow.

The cities were hungry for tunnels for their railways and channels, but the advance of steam machines was one to two meters a day … and the electricity advanced between two and five meters a day. The height is that they had reliability problems and the operators had to hold the tunnel in a traditional way.

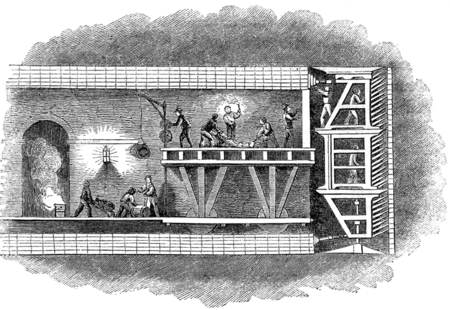

Mid a century to all fuse. In addition to the technical problems, the tunneladoras continued to have problems with the hard rock. The operators needed to resort to blasting, which made everything slower and dangerous, but in the 50s, the American James S. Robbins came up with something that revolutionized the panorama: a rotating head that mixed the previous advances.

The Oahe Dam tunnelador was the first modern tunnelora and had a rotating head that equipped drag cutters and disc. The tandem allowed working on tougher land continuously and, in addition, supposed the culmination of Brunel’s idea: the head perforated and the shield protected the operators who were placing the tunnel lining as the set advanced. It was also safer for these operators and the advances gave way to maximum speeds of about 200 meters a week, according to the land.

The head of Oahe’s tunnel bunker, the first modern tunnel

Stagnation. In half a century, the speed had multiplied by ten at best, but the advances of the 21st century were by other paths. The machines continued to evolve and perfect the idea of that hybrid robbins ‘morro’. They also became larger, efficient, safe and with automated systems when placing reinforcements. But despite all improvements, speed did not multiply as in past decades. He folded, but there is a problem: this speed is the theoretical one, not the real one.

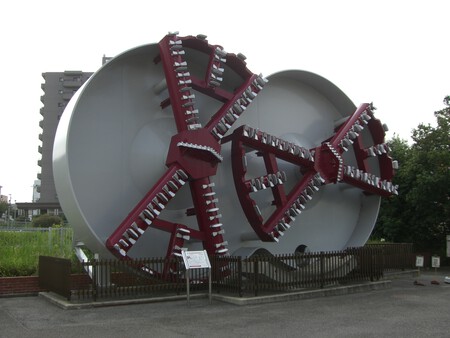

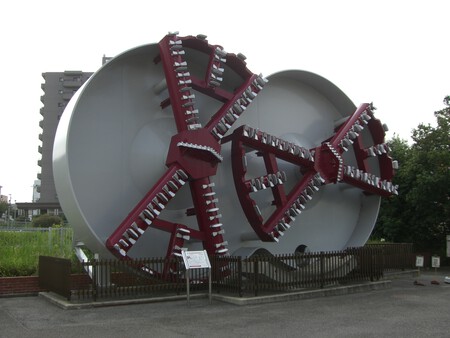

Jaws from the front of a double -shaped tunnelador ‘or’

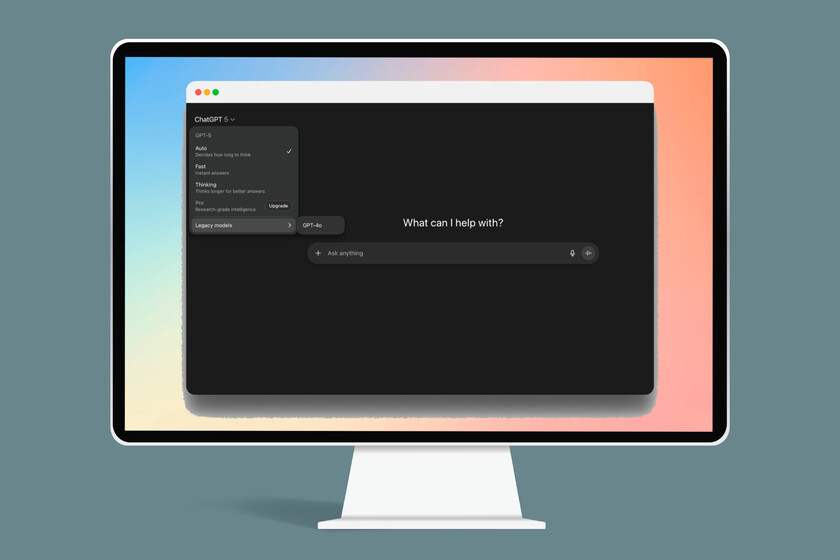

Llega The Boring Company. There Elon Musk enters the scene with his The Boring Company (an interesting game, since Boring Machine is “Boring Machine”, but it is also how the tunneladores is known). The businessman had the Hyperloop project, which made sense to have a tunnel company company, and the objective was to drastically increase the excavation speed.

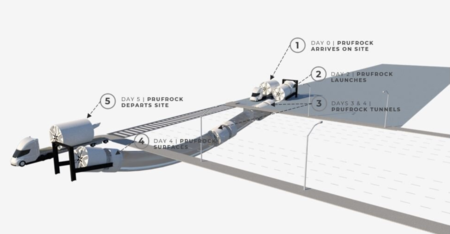

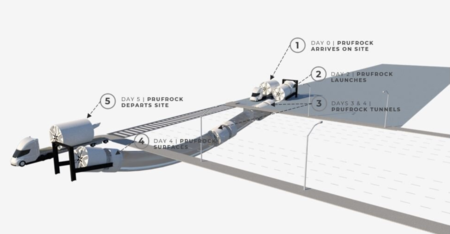

Your goal? Overcome the speed of 140 meters daily of a snail, 980 a week. PRUFROCK is his great bet with, a promised speed of more than 1,600 meters per week and an objective of 80,000 meters per week. It is an objective that seems utopian, but its idea is that machines work without stopping to maintain or to install the coating. Instead of installing the traditional transport rails of coating segments, the machine is more autonomous and that rail installation time is eliminated to transport the segments of the tunnel coating.

The idea of The Boring Machine is to release the tunnelador, to start excavating uninterruptedly and returns to the surface. It is good, but in urban land and unstable land, it is more utopian

It is really not novel because there are other machines that do it, but on soft land, working without coating can be dangerous. In current projects, such as Line 2 of the Lima Metro, the speed is around 15 meters per day and everything has to do because the land is complex and urban. There are many factors to consider when talking about the speed of these machines, go.

La Prufrock

What if the race is no longer the speed? Leaving aside the objectives of The Boring Company, the problem may want faster machines when progress are being made in a more important area: safety. Because, although the machines are now more capable and their speed has increased slightly, that apparent stagnation can respond to a change in objective.

The speed of the machines is conditioned by geology, by the logistics of evacuation of debris, by the lining and safety assembly of all those who are working inside the newly excavated tunnel. They could go faster, but precision and safety over maximum speed is prioritized. And an example is China.

China and priorities. The Asian giant is synonymous with investment in tunneladoras with huge machinery that is able to follow the rhythm of infrastructure plans in the country. Combining huge and powerful machines with more classic techniques such as blasting, China is undertaking works of great difficulty, and does so with machines whose greatest advance is not speed, but sustainability and safety.

As we said, this is a crucial element and, for example, one of its last tunneladores is able to detect the conditions of the land 40 meters ahead to make autonomous decisions. They are also investigating ways to optimize energy use and reduce emissions so that they are more sustainable.

Therefore, the speed of the tunneladoras may not increase as surprisingly as seen a few decades ago, but they are progressing quickly in another direction. Could they be faster? Yes, but it gives the feeling that they do not want for a change in priorities.

Images | TRJN, TBM, Robbins, Tambo

In WorldOfSoftware | England and Ireland wanted to create the longest tunnel in the world. A “stupid” and “advanced in your time”