At CES 2026, Nvidia Corp. Chief Executive Jensen Huang once again reset the economics of artificial intelligence factories.

In particular, despite recent industry narratives that Nvidia’s moat is eroding, our assessment is the company has further solidified its position as the hardware and software standard for the next generation of computing. In the same way Intel Corp. and Microsoft Corp. dominated the Moore’s Law era, we believe Nvidia will be the mainspring of tech innovation for the foreseeable future.

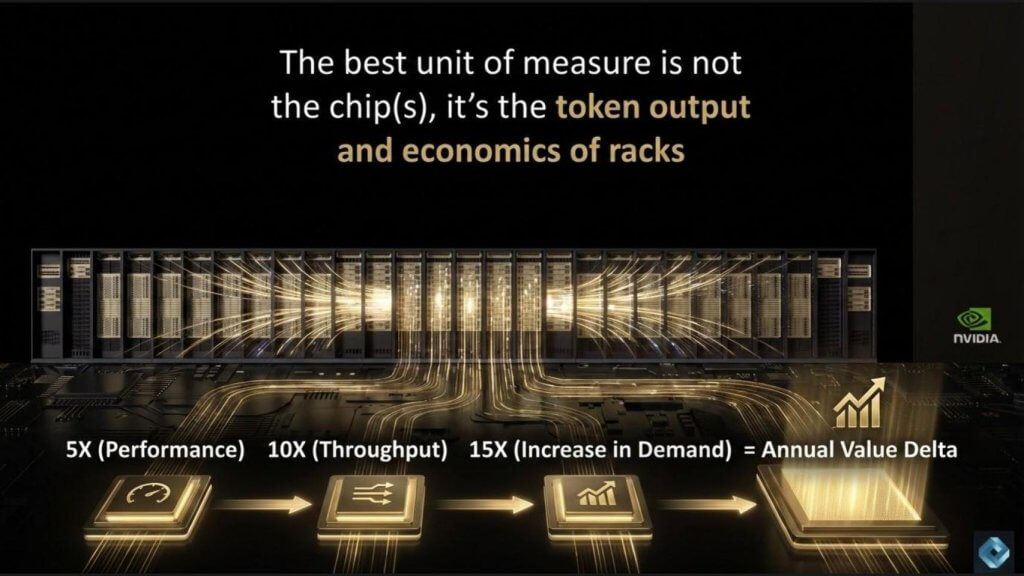

Importantly, the previous era saw a doubling of performance every two years. Today Nvidia is driving annual performance improvements of five times, throughput of 10 times, and driving token demand of 15 times via Jevons Paradox.

The bottom line is that ecosystem players and customers must align with this new paradigm or risk a fate similar to that of Sisyphus, the beleaguered figure who perpetually pushed a rock up the mountain.

In this Breaking Analysis, we build on our prior work from Episode 300 with an update to our thinking. We begin with an historical view, examining the fate of companies that challenged Intel during the personal computer era and the characteristics that allowed a small number of them to survive and ultimately succeed.

From there, we turn to the announcements Huang (pictured) made at CES and explain why they materially change the economics of AI factories. In our view, these developments are critical to understanding the evolving demand dynamics around performance, throughput and utilization in large-scale AI infrastructure.

We close by examining the implications across the ecosystem. What does this mean for competitors such as Intel, Broadcom Inc., Advanced Micro Devices Inc. and other silicon specialists? How should hyperscalers, leading AI research labs, original equipment manufacturers and enterprise customers think about AI strategy, capital allocation and spending priorities in light of these shifts?

Lessons from the PC era: Who survived Intel — and why

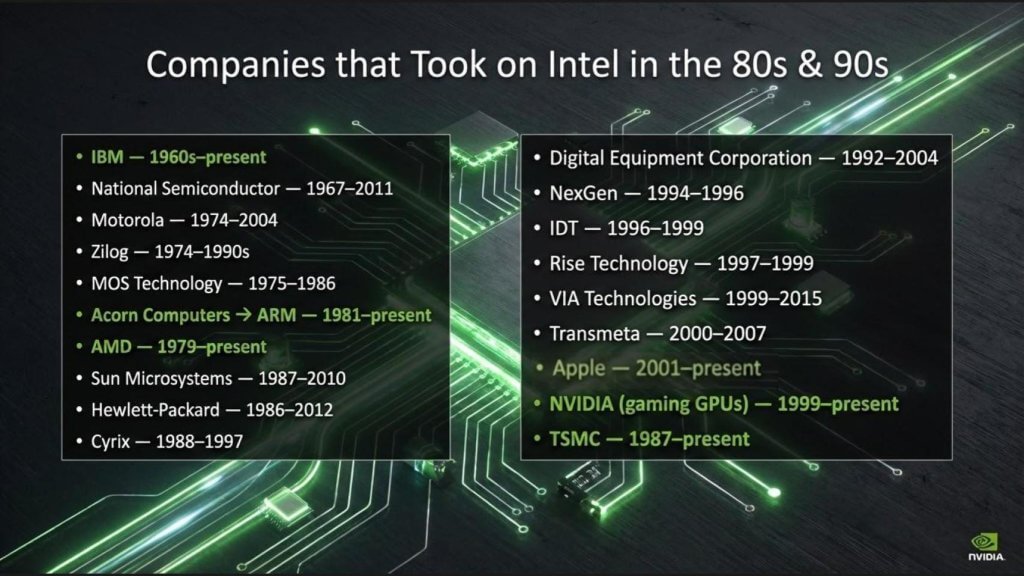

Let’s begin with a historical view, looking back at the companies that challenged Intel during the 1980s and 1990s. IBM was the dominant force early on, but it was far from the only player that attempted to compete at the silicon level. A long list of RISC vendors and alternative architectures emerged during that period – including Sun Microsystems Inc. – many of which are now footnotes in computing history.

The slide above highlights this reality. The companies shown in green are the ones that managed to make it through the knothole. The rest did not.

The central reason comes down to the fact that Intel delivered relentless consistency with predictable, sustained improvement in performance and price-performance, roughly doubling every two years. Intel never took its foot off the pedal. It executed Moore’s Law as an operational discipline as well as a technology roadmap. As a result, competitors simply could not keep pace. Even strong architectural ideas from industry leaders were overwhelmed by Intel’s scale, manufacturing advantage, volume economics and cadence.

One point worth noting. Apple, while not always viewed as a direct silicon competitor during that era, ultimately won by controlling its system architecture and, later, by vertically integrating its silicon strategy.

The broader takeaway is fundamental in our assumptions for the rest of this analysis. Specifically, in platform markets driven by learning curves, volume and compounding economics, dominance is not just about having a great product. Success requires sustained momentum over long periods of time, while competitors exhaust themselves trying to catch up.

The survivors: Why those companies made it through

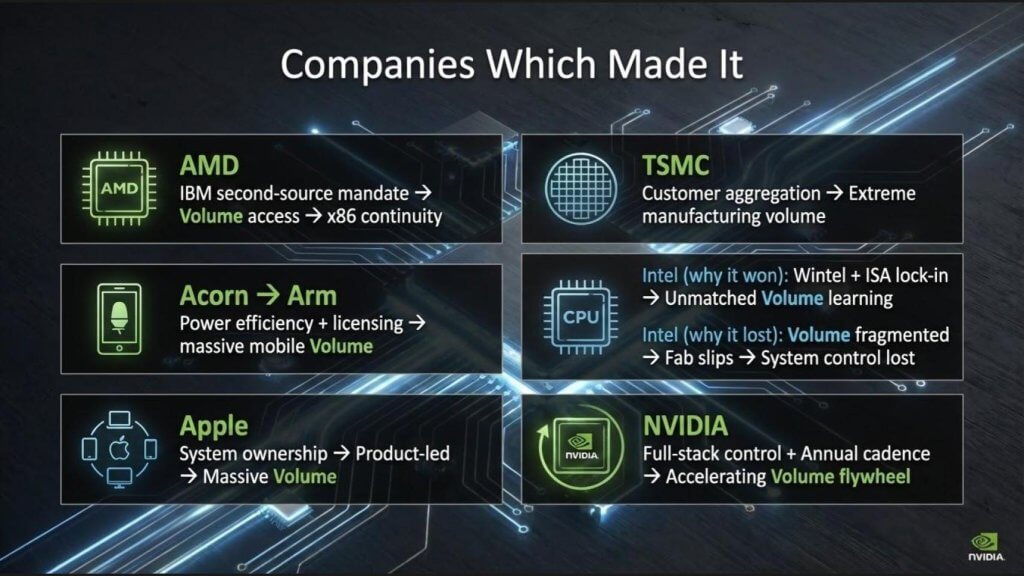

Let’s now double down on the companies that actually survived the Intel-dominated PC era. The list below is instructive in our view. AMD, Acorn (the original Arm), Apple Inc., Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. Intel and Nvidia. Each followed a different path, but they share a common underlying characteristic which is volume.

AMD’s survival traces directly back to IBM’s original PC strategy. IBM mandated a second-source supplier, forcing Intel to share its instruction sets. AMD became that second source, and no other company gained comparable access. That structural advantage persisted for decades and allowed AMD to remain viable long after other x86 challengers disappeared.

ARM, TSMC and Apple fundamentally changed the prevailing belief – stated by AMD CEO Jerry Sanders— that “real men own fabs.” These companies proved that separating design from manufacturing could be a winning strategy. Apple brought massive system-level volume. TSMC rode that volume to drive down costs, ultimately achieving manufacturing economics that we estimate to be roughly 30% lower than Intel’s. Nvidia followed a similar fabless path, pairing architectural leadership with accelerating demand. Intel itself was the original volume powerhouse, benefiting from the virtuous cycle created by the Wintel combination. That volume allowed Intel to outlast RISC competitors and dominate the PC era. But in the current cycle, Intel has lost ground to Arm-based designs, Nvidia and TSMC – each of which now rides on steeper learning curves.

The takeaway is that volume is volume is fundamental to dominance. Not just volume in a single narrow segment, but volume across adjacent and synergistic markets that feed the same learning curves. AMD’s volume was initially forced by IBM’s PC division mandating a second source to Intel. Apple’s volume is consumer-driven. TSMC’s volume is manufacturing-led. Nvidia’s volume is now accelerating faster than any of them in this era.

In our view, Nvidia is positioned to be the dominant volume leader of the AI era by a wide margin. And as history shows, once volume leadership is established at scale, it becomes extraordinarily difficult for competitors to catch up without other factors affecting the outcome (e.g. self-inflicted wounds or things out of the leader’s control such as geopolitical shifts).

What Nvidia announced at CES: Extreme co-design becomes the differentiator

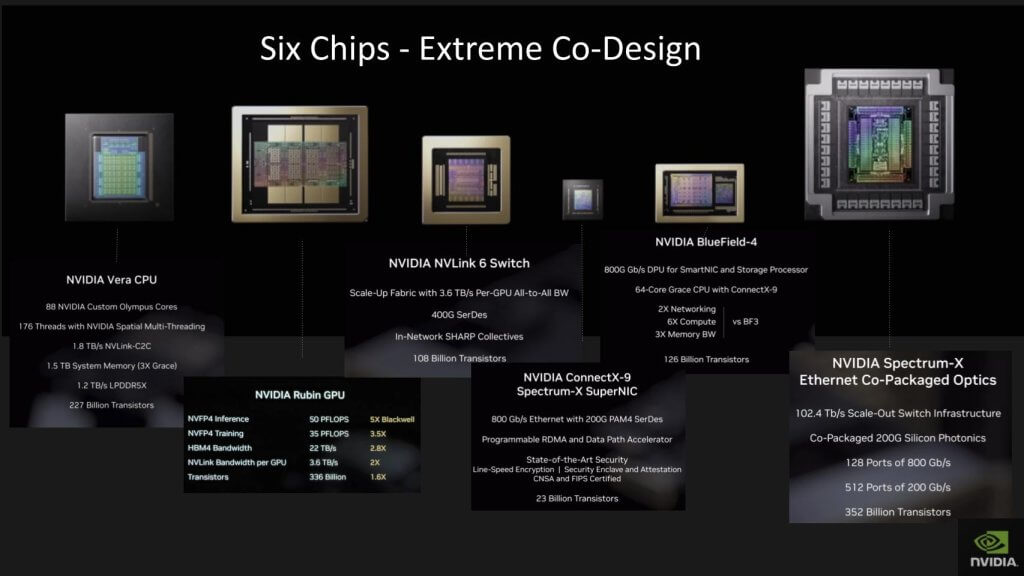

Nvidia’s CES announcements were visionary and focused largely on the emerging robotics market. In this analysis, however, we focused in on the core of Nvidia’s systems business. In our view, what Nvidia announced in this regard exceeded even our optimistic expectations. As we’ve stressed often, Nvidia is remarkable, not only because of a single chip, but because of the scope of what it delivers. Specifically, Huang led this part of his keynote with a six-chip, full-system redesign built around what Huang consistently refers to as extreme co-design.

The chart above shows the next generation innovations from Nvidia, including Vera Rubin, named in homage to the astronomer whose work on galactic rotation curves led to the discovery of dark matter. Vera is the CPU. Rubin is the GPU. But focusing only on those two components misses the broader story. Nvidia simultaneously advanced every major silicon element in the system including NVLink based on InfiniBand, ConnectX nics and Spectrum-X for Ethernet, BlueField DPUs and Spectrum-X Ethernet with co-packaged optics.

A few years ago, the prevailing narrative suggested that Ethernet would undercut Nvidia’s proprietary networking position, the underpinning which was Infiniband (via the Covid-era Mellanox acquisition). Nvidia was undeterred and responded by building Spectrum-X. Today, Jensen Huang argues that Nvidia is the largest networking company in the world by revenue, and the claim appears credible. What’s striking is not the line extension itself, but the speed and completeness with which Nvidia executed it.

The deeper point lies in how Nvidia defines co-design. While the company works closely with customers such as OpenAI Group PBC, Google LLC with Gemini and xAI Corp., the co-design begins internally – across Nvidia’s own portfolio. This generation represents a ground-up redesign of the entire machine. Every major chip has been enhanced in coordination, not in isolation.

The performance metrics are astounding. The GPU delivers roughly a fivefold performance improvement. The CPUs see substantial gains as well. But equally important are the advances in networking – both within the rack and across racks. Each subsystem was redesigned together to maximize end-to-end throughput rather than optimize any single component in isolation.

The result is multiplicative, not additive. While individual elements show performance gains on the order of five times, the system-level throughput improvement is closer to an order of magnitude. That is the payoff of extreme co-design – aligning compute, networking, memory and software to minimize single bottlenecks that limit the overall system.

In our view, this marks a decisive shift in how AI infrastructure is built. For quite some time we’ve acknowledged that Nvidia is no longer shipping chips. It is delivering tightly integrated systems engineered to maximize throughput, utilization, and economic efficiency at the scale required for AI factories. That distinction is profound as competitors attempt to match not just component performance, but the learning-curve advantages that emerge when volume, architecture and system-level design reinforce each other. While Jensen has pointed out that Nvidia is a full systems player, the point is often lost on investors and market watchers. This announcement further underscores the importance of this design philosophy and further differentiates Nvidia from any competitor.

Metrics that matter: From chips to racks to tokens

A critical point that becomes more clear from Nvidia’s announcements is the chip is not the correct unit of measurement. The system is. More precisely, the rack – and ultimately the token output per rack – is what defines performance, economics, and value.

Each rack integrates 72 GPUs along with CPUs and high-speed interconnects that bind the system together. Compute density is critical, but so is the ability to move data with minimal jitter and maximum consistency – within the rack, across racks, and across entire frames. Nvidia has dramatically increased memory capacity into the terabytes, enabling GPUs to operate in tight coordination without stalling. The result is coherent execution at massive scale.

These systems are designed to scale up, scale out, and scale across. When deployed at full factory scale, they operate not in dozens or hundreds of GPUs, but in hundreds of thousands – eventually up to a million GPUs working together. As scale increases, so does throughput. And as throughput increases, the economic value of the tokens generated accelerates.

This is where the numbers compound to create the flywheel effect. Roughly five times performance improvement at the component level combines with roughly ten times throughput at the system level. Together, they drive what we believe is an estimated 15-times increase in demand, as lower cost per token unlocks entirely new classes of workloads. This is Moore’s Law on triple steroids – and it explains why annual value creation rises so sharply.

The Jevons Paradox applies here. As the efficiency of token generation improves, total consumption rises. As we’ve stressed, the value shifts away from static measures of chip performance, toward dynamic measures of system utilization and output economics. The faster tokens can be generated, the more economically viable it becomes to deploy AI at scale, and the more demand expands.

Networking is central to this equation. Nvidia’s long-term investment in Mellanox – once dismissed by many as a bet on a dying technology – now looks prescient. InfiniBand continues to grow rapidly, even as Ethernet demand also accelerates. Far from being a bottleneck, networking has become a core enabler of system-level performance.

The takeaway is that AI infrastructure economics are now defined at the rack and factory level, not at the chip level. Nvidia’s advantage lies in designing systems where compute, memory, networking and software operate as a single, tightly coordinated machine. That is where throughput is maximized, token economics are transformed, and the next phase of AI factory value is being created.

Training, factory throughput and token economics: The gap is widening

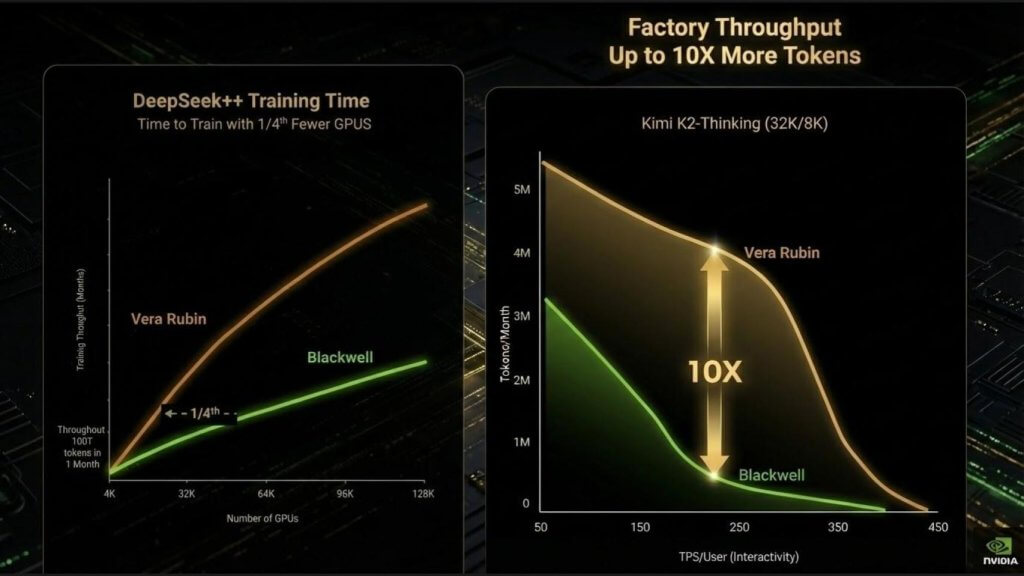

Huang presented three critical metrics on a single slide to show training throughput, AI factory token throughput and token cost. Together, they tell a story about where AI infrastructure economics are headed. For clarity, we break this into two parts as shown below: training on the left, factory and inference throughput on the right.

The training chart shows time-to-train measured in months for a next-generation, ultra-large model. The takeaway is eye opening. The Rubin platform reaches the same training throughput as Blackwell using roughly one quarter of the GPUs. As we pointed out earlier, this is not simply about faster chips. It reflects dramatic gains in efficiency at scale – reduced synchronization overhead, fewer memory stalls, lower fabric contention, and shorter training cycles overall.

The implications are notable. Capital required per model run drops materially. Customers can run more experiments per year and iterate faster. Training velocity becomes a competitive advantage in itself, not just a cost consideration. In our view, this is one of the most under-appreciated dynamics in the current AI race.

The factory throughput chart above on the right, tells an equally important story. As workloads shift from batch inference toward interactive, agent-driven use cases, throughput characteristics change dramatically. Tokens per query increase. Latency sensitivity rises. Under these conditions, Blackwell’s throughput collapses as shown. Meanwhile, Rubin sustains performance far more effectively and delivers approximately 10 times more tokens per month at the factory level.

This is the future workload profile of AI factories – real-time, interactive, agentic and highly variable — not static batch inference. Rubin is designed for this moment. The value is not just in peak performance, but in sustained throughput under real-world conditions.

Taken together, these charts explain why Nvidia’s advantage continues to widen. Training and inference are converging in economic importance. Faster training reduces capital intensity and accelerates innovation. Higher factory throughput lowers token costs while expanding demand. This combination resets expectations for performance, efficiency and scalability.

In our view, many observers continue to underestimate both the pace at which Nvidia is moving and the magnitude of the gap it is creating. Comparisons to alternative accelerators – whether Google TPUs, AWS Trainium or others – miss the system-level reality being demonstrated by Nvidia. The new standard is not raw compute. It is training velocity, sustained factory throughput and token economics at scale. And on those dimensions, Nvidia is setting the bar.

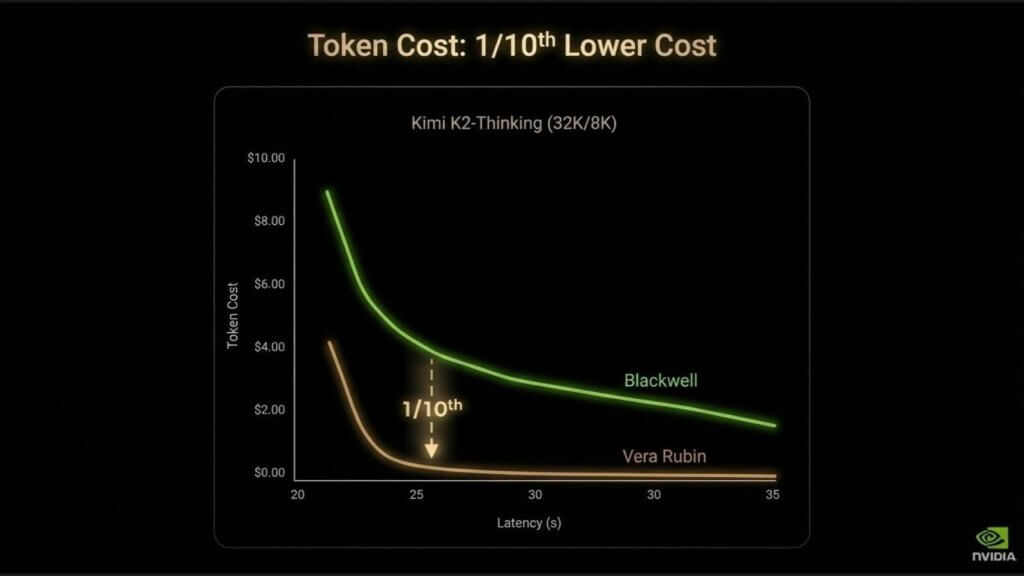

Cost per token: How the economics have reset

The final piece of the equation that we’ll dig into is cost. And this is where the implications become overwhelming. In our view, it’s what matters most.

The combination of higher throughput and system-level efficiency drives cost per token down by roughly an order of magnitude. Huang framed it in his keynote saying these systems may consume more power, but they do vastly more work. When throughput rises by 10 times and cost per token falls to one-10th, the economic profile of AI factories fundamentally resets.

What’s striking is the pace. This is not the 18- to 24-month cadence historically associated with Moore’s Law. These gains are occurring on a 12-month cycle. Moore’s Law transformed the computing industry for decades, lifting productivity across silicon, software, storage, infrastructure and applications. What we are seeing now is an even more aggressive curve – orders-of-magnitude improvement compressed into a single year.

There are real pressures behind this progress. Demand for advanced chips, memory and interconnects is intense, pushing up component costs. Nvidia has secured premium access across that supply chain. But from the perspective of an AI factory operator, the math dominates everything else. If cost per token falls while throughput rises dramatically, the earning power of the factory increases materially.

This is especially critical in a power-constrained world as we described last August when we explored the “New Jensen’s Law.” Hyperscalers and neoclouds alike are limited by available power, not just capital. Under those constraints, Jensen’s tongue-in-cheek “law” applies – buy more, make more; or buy more, save more. The ability to extract significantly more work from the same infrastructure — or achieve the same output with far less — translates directly into financial operating leverage.

The example Jensen cited makes the point concrete. In a $50 billion, gigawatt-scale data center, improving utilization by 10% produces an enormous $5 billion benefit that flows straight to the income statement. That is why networking, in this context, becomes economically “free.” The incremental cost is dwarfed by the utilization gains it enables.

This is ultimately why Nvidia’s position is so strong. The advantage is not just technical – it’s economic. Nvidia is operating on a steep learning curve, reinforced by volume, system-level co-design and accelerating efficiency gains. When cost per token collapses at this rate, demand expands, utilization rises and the economics compound. That dynamic is what defines leadership in this era.

Competitive implications: Pressure points, leverage and where’s the white space

We’ll close by translating the CES announcements into competitive implications across multiple classes of players, including vendors that are simultaneously customers. The common theme is that the unit of competition has shifted from chips to systems, racks and ultimately token economics. That shift changes the survivability economics for incumbents, the opportunity for specialists, and the urgency of customer strategies.

Intel: A path back through CPU relevance, not monopoly

In our view, it’s effectively game over for Intel’s historical monopoly and leadership position. The more interesting question is whether Intel can remain a meaningful CPU provider in an AI factory world – and the Nvidia/Intel interoperability move is notable in that context.

The historical context is relevant. Nvidia has wanted deeper access to x86 since the late 1990s but was never allowed. The new arrangement changes the structure and it enables a configuration where Intel CPUs and Nvidia GPUs can operate within the same frame. It’s not a fully unified architecture, but it is sufficient for most of the work, and it creates a practical path for Intel CPUs to remain present in these systems.

It also gives Intel a meaningful level of access to CUDA-based environments – short of “full access,” but still consequential. The net effect should improve Intel connectivity in these deployments, keep Intel in the CPU game for this cycle, and increase the volume of Nvidia systems available to the market. In other words, it can act as a viable bridge from the old to the new, which is good for customers.

We do want to flag a key risk to any optimistic Nvidia scenario – a Taiwan geopolitical disruption. If China takes over Taiwan, there are multiple potential outcomes – from continuity with a new lever for China, to a more disruptive scenario if that lever is pulled. Either would ripple through sentiment around Nvidia and could increase perceived strategic value for Intel. But the hard reality is Intel still has to close the manufacturing and execution gap with TSMC, and that is not something any company can leapfrog overnight.

AMD: Strong against Intel, misaligned against Nvidia – so look to the edge

AMD has executed well against Intel in x86. But the competitive target has shifted. x86 is mature and its curve has flattened, which made the timing right for AMD’s ascdendency and for hyperscalers to pursue alternatives such as AWS’ Graviton. AMD is now taking on a very different animal – a leader moving on a steep learning curve with compounding system-level advantages.

In our view, the core issue is speed. AMD will struggle to move fast enough to close a gap defined by 12-month cycles and system-level throughput economics. One practical implication is that AMD should pursue a deal structure similar to Intel’s – something that secures volume on one side – while focusing aggressively on the edge. Data center CPU revenue is meaningful for Intel and AMD, but expanding volume there will be difficult, and there is real risk of decline. The edge remains wide open, and that’s where focus should go in our opinion.

At the same time, it’s important to recognize that Nvidia is also targeting the edge – autonomous vehicle libraries were highlighted and robotics were put on stage at CES and it’s a major focus of the company. The edge is open, but it won’t be uncontested.

Silicon specialists: Big opportunity but not by taking Nvidia head-on

There is ample room for specialists that avoid direct, frontal competition with Nvidia. The AI factory buildout is forecast to be enormous – large enough that niche and adjacency strategies can still create meaningful businesses, particularly around factories and the edge.

Two examples we cite:

- Cerebras: Strong technology, but not a durable moat if the broader packaging and manufacturing capabilities being normalized at TSMC expand the feasible chip/system envelope for everyone —including Nvidia.

- Groq: Latency leadership. Low latency is critical for inference. If latency improves, both demand and throughput can expand significantly. A Groq + Nvidia combination was a smart move by Nvidia if allowed to proceed and will be powerful by pulling latency advantages into Nvidia rack-scale systems.

But the strategic point is that latency is a real lever in inference economics, and specialists that win on latency can matter – especially at the edge.

Broadcom and hyperscalers: ASIC supply chain power vs. strategic focus

Broadcom is best understood as a critical supplier to hyperscalers, OEM ecosystems, mobile players and virtually all forms of connectivity. Broadcom has a custom silicon engine that manages back-end execution with foundries and manufacturing partners. Its business is diversified and structurally important, and we do not view it as going away by any means. Broadcom has deep engineering talent and a diversified business with exceptional leadership.

The more controversial question is whether hyperscalers should continue investing in alternative accelerators such as TPUs, Trainium and other ASIC strategies – as a long-term path to compete with Nvidia.

Google and TPUs: ‘Can’ vs. ‘should’

Google has deep history and real technical credibility with TPUs. But the argument here is that this is now a different business environment. Google must protect search quality and accelerate Gemini. If internal platform choices limit developer access to CUDA and the best available hardware/software improvements, the risk is that Gemini’s development velocity slows. If model iteration takes multiples longer, that becomes strategically dangerous.

Our view is that TPUs have reached a ceiling in this context – not because they can’t improve, but because they cannot match Nvidia’s volume-driven learning curve and system-level economics, particularly with networking as scale.

- Volume: TPUs operate at a fraction of Nvidia’s volume, and volume drives learning curves;

- Scaling bottleneck: At very large scales, networking becomes the limiter, and our argument is that TPUs will hit a scaling wall as factories move into hundreds of thousands and millions of accelerators;

- System economics: It’s not “the ASIC” that matters; it’s the whole frame. Competing requires building the full-stack system business for a market that is far smaller than Nvidia’s.

A related point, made by Gavin Baker using a simplified economics example is if Google’s TPU program represents a $30 billion business, and it sends a large portion of value to Broadcom (about $15 billion), one might argue for vertical integration. The counterargument here is that even if it’s financially possible, it may be strategically irrational if it slows Gemini’s iteration speed. The core thesis is that Google should prioritize model velocity over accelerator self-sufficiency.

The same logic extends to Trainium. AWS’ Graviton playbook worked because it targeted a mature, flattening x86 curve. That is not the environment in accelerators today. The pace is too fast, the curves are too steep, and the system complexity is too high.

Will AWS, Google and even Microsoft continue to fund alternatives to Nvidia? Probably as use cases will emerge for more cost effective platforms. But the real strategic advantage for hyperscalers in our view lies elsewhere, especially as they face increasing competition from neoclouds.

Frontier AI research labs: Allocation, volume and who stays ahead

We position four frontier labs as the primary contenders: OpenAI, Anthropic PBC, Google and xAI Corp.’sGrok, with Meta Platforms Inc.treated as a second tier (with the caveat that it’s unwise to count Zuckerberg out).

Despite persistent negative narratives around OpenAI — especially around financing structure and commitments — our view is that pessimism may be misplaced. The reasoning is as follows:

- OpenAI leads in adoption and user usage by a wide margin;

- OpenAI has pursued as much processing capacity as possible from wherever it can be sourced. This is a key bottleneck and Sam Altman is positioning to be first to market;

- We continue to see OpenAI, in combination with Microsoft, as winning on volume – alongside Grok – creating a structural advantage that makes life harder for Gemini long-term and challenging for Anthropic if they don’t lean into the Nvidia stack to the same degree as OpenAI and Elon.

In short, we see the winners as OpenAI the most likely overall winner in the center, with Anthropic as the second player, and Grok highly likely to do well at the edge. Elon could also compete strongly at the edge while he backed away from the idea of building his own data center chips.

An additional allocation nuance is labs aligned with Nvidia (OpenAI and X.ai) may have a better path to “latest and greatest” allocations than those pursuing tighter coupling with alternative accelerator strategies.

OEMs: Dell, HPE, Lenovo, Supermicro

For OEMs like Dell, HPE, Lenovo, and Supermicro, the opportunity is primarily executional. In other words, get the latest platforms, package them, deliver them, and keep them running reliably without thermal or integration failures. Demand is enormous, supply is constrained, and this is not a zero-sum game. For now they can all do well.

The key point is that as long as the market remains supply-constrained, anything credible that can be produced will be consumed. That reality can justify multiple silicon suppliers from the ecosystem – even if the long-run competitive curve still favors Nvidia.

Customers: AI strategy and spending implications

On the customer side, we challenge a widely repeated narrative to “get your data house in order before you spend on AI.” The view here is that this sequencing can be backwards.

Our modeling suggests that over a multi-year period (for example, five years), getting onto the AI learning curve earlier can generate substantially more value than delaying until data is “clean.” Even if data isn’t pristine, organizations can choose a dataset, apply AI to improve it, and compound learning rather than waiting.

Two additional implications are highlighted below:

- IT spend as a percentage of revenue may rise materially—from roughly about 4% of revenue today toward about 10% or more – driven by productivity and value;

- Tech spend shifts from “MIPS” to tokens. Our belief is that tokens become the unit of value and spending shifts heavily toward API-accessible intelligence over the next decade, potentially on the order of 10:1.

Our strategy recommendation is to optimize for speed and learning. Put token capacity close to data (latency matters), use tokens to improve access and data quality, then iterate through AI projects quickly – one project, learn, then the next, building a flywheel. The emphasis should be on starting from value and using intelligence to improve the systems, rather than spending years trying to perfect data first.

Closing thought

In our view, the defining lesson of this analysis is that AI is no longer a contest of individual chips, models, or even vendors – it is a contest of learning curves, systems and economics. History shows that in platform transitions, leadership accrues to those who achieve volume, sustain execution and convert efficiency gains into expanding demand. That dynamic shaped the PC era, and it is repeating at far greater speed in the AI factory era.

What differentiates this cycle is the compression of time. Improvements that once unfolded over decades are now occurring in 12-month intervals, resetting cost structures and forcing strategic decisions faster than most organizations are accustomed to making them. The implications go across silicon providers, hyperscalers, AI labs, OEMs and enterprises alike.

For customers, the message is value will accrue to those who get onto the AI learning curve early, focus on throughput and token economics, and build momentum through rapid iteration rather than waiting for perfect conditions. For vendors, survival will depend less on clever alternatives and more on whether they can stay on the steepest curves without slowing themselves down.

This transition will not be linear, and it will not be evenly distributed. But the direction is clear in our view. AI factories are becoming the economic engine of the next computing era, and the winners will be those who treat AI not as a feature or experiment, but as the core operating model of their business.

Disclaimer: All statements made regarding companies or securities are strictly beliefs, points of view and opinions held by News Media, Enterprise Technology Research, other guests on theCUBE and guest writers. Such statements are not recommendations by these individuals to buy, sell or hold any security. The content presented does not constitute investment advice and should not be used as the basis for any investment decision. You and only you are responsible for your investment decisions.

Disclosure: Many of the companies cited in Breaking Analysis are sponsors of theCUBE and/or clients of Wikibon. None of these firms or other companies have any editorial control over or advanced viewing of what’s published in Breaking Analysis.

Image: Nvidia/livestream

Support our mission to keep content open and free by engaging with theCUBE community. Join theCUBE’s Alumni Trust Network, where technology leaders connect, share intelligence and create opportunities.

- 15M+ viewers of theCUBE videos, powering conversations across AI, cloud, cybersecurity and more

- 11.4k+ theCUBE alumni — Connect with more than 11,400 tech and business leaders shaping the future through a unique trusted-based network.

About News Media

Founded by tech visionaries John Furrier and Dave Vellante, News Media has built a dynamic ecosystem of industry-leading digital media brands that reach 15+ million elite tech professionals. Our new proprietary theCUBE AI Video Cloud is breaking ground in audience interaction, leveraging theCUBEai.com neural network to help technology companies make data-driven decisions and stay at the forefront of industry conversations.