If today we think of an astronaut, we usually imagine someone with advanced scientific training, prepared to live for weeks or months in a challenging environment, master complex systems, robotics and even several languages. But in the sixties, when the space race was a race of speed and prestige, the mold was different: NASA was looking for operational profilespeople capable of making decisions under pressure and flying machines that no one had flown before. That was the pattern that marked almost the entire Apollo program. And yet, there was one exception that broke the norm: for the first and only time, one of those who set foot on the Moon was specifically selected as a scientist, and that influenced what we learned about it.

The protagonist of this exception was Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt, and his case is unique within the lunar program. On Apollo there were astronauts with doctorates or advanced technical training, yes, but that does not automatically make them “scientist-astronauts.” The difference is in the selection criteria. Buzz Aldrin, for example, had a doctorate in astronautics, but entered the astronaut corps through the usual route of the military pilot (Group 3), like so many others. In June 1965, according to NASA, a specific group was selected to recruit scientists, Group 4, and Schmitt was the only member of those members who ended up assigned to a moon landing mission, Apollo 17.

The astronaut who came to be a scientist

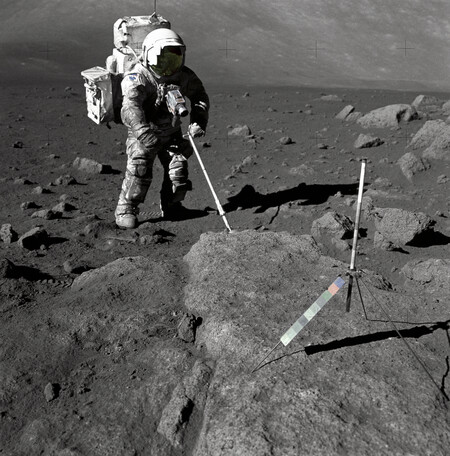

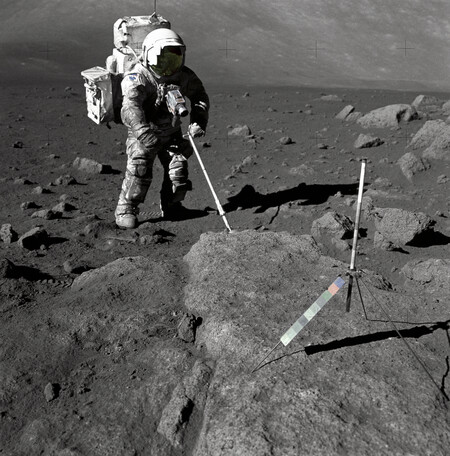

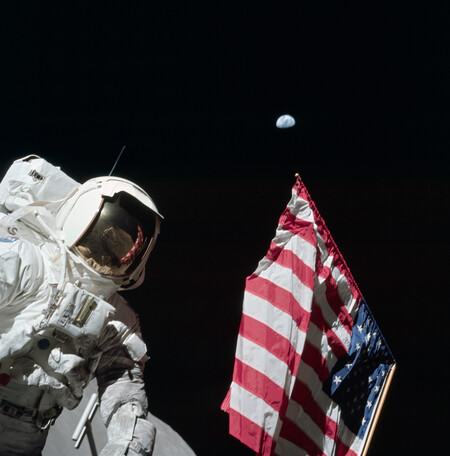

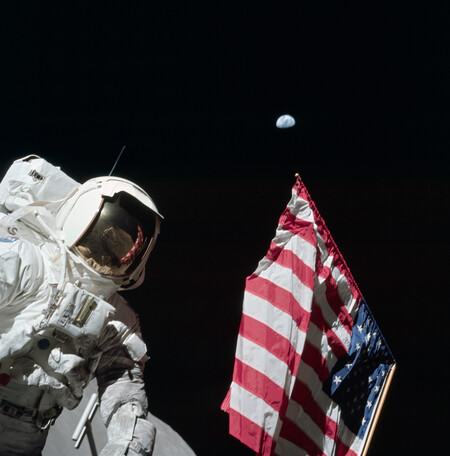

Before becoming an astronaut, Schmitt was already working, literally, with the Moon in mind. According to the USGS, in 1964 he joined the Astrogeology team at the Flagstaff Science Center as a geologist after receiving his doctorate from Harvard. participated in lunar geological mapping and led the Lunar Field Geological Methods project, focused on how to do field geology applied to satellite exploration. That experience put him in a unique position within the program: He was not a newcomer to lunar science. After joining NASA, his contribution went beyond flight. The Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition emphasizes that it organized the lunar scientific training of the Apollo astronauts, represented the crews during the development of hardware and procedures for exploring on the surface, supervised the final preparation of the descent stage of the Apollo 11 lunar module, in addition to serving as a mission scientist.

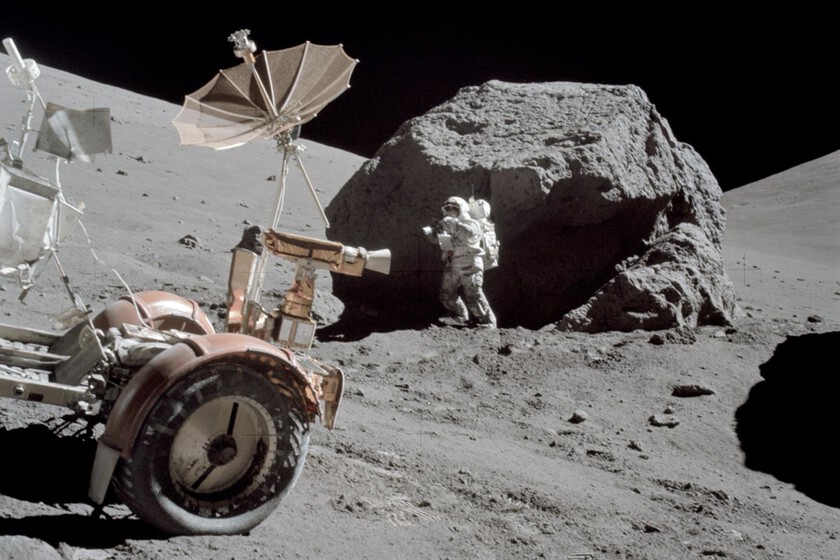

Apollo 17 was not just another mission within the program. NASA defined it as the last of the three J-type missions, a series characterized by greater hardware capacity, more scientific load and the use of the Lunar Roving Vehicle, the electric rover that expanded the actual exploration radius. That explains why the exploration of the Taurus-Littrow valley was not chosen at random. The objective was ambitious: to work in an area where rocks older and younger than those recovered in previous missions could be found. Added to this scientific ambition was an operational design with room to deploy and activate surface experiments, perform sampling, and complete photographic and experimental tasks both in lunar orbit and upon return to Earth.

In an interview with the Japanese space agency (JAXA), Schmitt explains that a specialist arrives with years of accumulated experience, and that allows him to decide much more quickly what is important and what is not. Schmitt recalls that NASA trained its pilot astronauts to observe well and understand the problems they were working on, but insists that there is no substitute for experiencewhether in geology, medicine or any other discipline. That is the practical logic that sustains their presence in Apollo 17: when the objective is no longer just to arrive, but to interpret an environment and choose samples judiciously, having someone on the ground who has done field geology for years changes the quality of the decisions.

And there appears one of the most remembered episodes of Apollo 17. In the middle of the field work in Taurus-Littrow, Schmitt and Eugene Cernan identified the so-called “orange soil”, a discovery that generated great expectation in the scientific community. Within the framework of the mission, this material has been described as volcanic glass or pyroclastic material, and is interpreted as especially clear evidence of ancient explosive volcanism on the Moon. It wasn’t just a color oddity. It was a clue about the thermal and geological history of the satellite, and a perfect example of why the mission had looked for a place where different materials could appear, older and also younger than those brought by other expeditions.

If Schmitt’s story seems strange it is because, within the same group of scientist-astronauts, he was the only one with a lunar destiny. The USGS notes that, From more than 1,000 applicants, six were selectedand that three of them, Joe Kerwin, Owen Garriott and Edward Gibson, would end up flying in Skylab in 1973 and 1974. That is, science, yes, but far from the moon landing. NASA wanted to reinforce the scientific component of manned flight, but the priority of the lunar program remained different and the space for “specialists” was limited. In this context, Schmitt stands out not only for stepping on the Moon, but for what it implies: even within a group created to add science, the moon landing remained almost exclusive territory of the operational profile.

Schmitt’s story has value precisely because it is not just a biographical oddity, it is a mirror. In Apollo, the ideal astronaut was an operator, and only once, in the last moon landing, that mold was opened to integrate someone selected for their scientific profile. As we have seen, currently, astronaut training is designed for long and complex missions, with different requirements. And right now, when the moon race looms again, that question makes sense. Since Apollo 17, in 1972, humans have not returned to the surface, but NASA proposes a way back with Artemis, with Artemis II as a manned flyby and Artemis III as the planned lunar landing if the plans are fulfilled. With China also targeting the satellite, the return is no longer read only in a historical key. Returning to the Moon implies deciding, again, if the objective is to reach or understand.

Images | POT

In WorldOfSoftware | Four astronauts are going to undertake an unprecedented journey to the Moon. They have no intention of stepping on it