Table of Links

Abstract and I. Introduction

II. Background and Related Work

A. Learning to Program: SCRATCH and Pair Programming

B. Gender in Programming Education and Pair Programming

III. Course Design

A. Introducing Young Learners to Pair Programming

B. Implementation of Pair Programming

C. Course Schedule

IV. Method

A. Pre-Study and B. Data Collection

C. Dataset and D. Data Analysis

E. Threats to Validity

V. Results

A. RQ1: Attitude

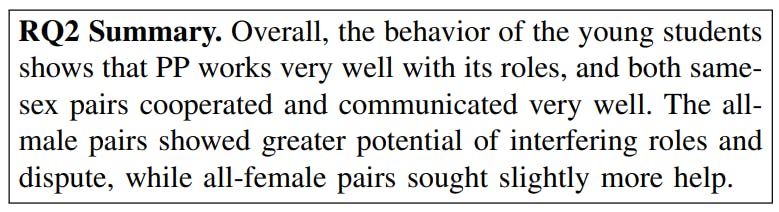

B. RQ2: Behavior

C. RQ3: Code

VI. Conclusions and Future Work, Acknowledgments, and References

B. RQ2: Behavior

To determine the behavior of students in their pairs during the course, we analyze the observations of the supervisors within six categories. Table IV shows the normalized values of these six observed categories for each pair per task.

1) Compliance: In terms of how well the pairs followed their assigned roles (CP), we observe marginal differences between both same-sex pairs (p = 0.332), with the all-female pair following them slightly more in each task (Table IV). However, we notice a significant difference in the fifth task (p = 0.031), where the all-male pairs followed their roles considerably less than the all-female pairs (Table IV). This may be due to the subject of the fifth task, where the students were given creative freedom to implement their own ideas, and where both boys of a team seemed to want to assert themselves (Figure 5) [41], [55]. Although not significant, a similar behavior can also be observed in the last task, which is the second offhanded creative task, and thus supports the theory of the assertion within all-male pairs. Overall, these results confirm prior observations that girls stick to instructions more often than boys due to socially expected behavior [3], [27], [28], [56], and this generalizes to PP.

2) Collaboration: Collaboration is essential for successful teamwork [1], [55]. Both same-sex pairs consistently collaborated very well (p = 0.608) (Table IV). While in the all-female pairs the first task is salient, possibly due to differences of opinion in the choice of sprites, in the all-male pairs almost all tasks are affected by outliers, especially for the last three tasks, where they were given greater freedom regarding the implementation of the tasks (cf. Section V-B4). However, the mixed pairs show a comparatively low level of collaboration (∅ 0.52), which may indicate conflicts between the sexes [41].

3) Communication: Communication is one of the key factors for successful teamwork. Analogously to the collaboration, we see little difference between the same-sex pairs (p = 0.379) (Table IV), but with a large difference to the mixed pairs (∅ 0.42). However, the all-female pairs communicate somewhat worse than the all-male pairs in the first and last tasks. In particular, in the first task, the distribution of both pairs is different, which has already been observed in the collaboration (cf. Section V-B2). Noticeably, the behavior seems to almost reverse in the last two tasks, where first the all-female pairs show a higher variance in communication than the all-male pairs, which might be a result of the boys finding the task difficult (cf. Section V-A2).

4) Dispute: When it comes to disputes between the pair members, we observe several differences: all-female pairs show the lowest conflict rates in total, while all-male pairs show a high potential of conflict (Table IV); the mixed pairs show the highest number of disputes (∅ 0.20). In particular, the tasks three, five and six led to most conflicts among the all-male pairs, with significant differences between the allfemale and all-male pairs for the third (p = 0.025) and fifth task (p = 0.022). This high conflict rate might be due to the demand for leadership, even at this young age [1], [27], [41], [55]. This is especially reflected in the fifth task, which has the lowest level of compliance, yet, the highest conflict rate among the all-male pairs, suggesting that the interference of assigned roles leads to a power struggle (Figure 5). Regarding the allfemale pairs, the first task led mainly to conflict (Table IV). Based on our observations, this might be due to the decision making when picking a sprite and background.

5) Harmony: Similar to the conflict rate, we see comparable values in the category to what extent the pairs dealt with each other harmoniously: likewise, the mixed pairs (∅ 0.57) are far below the same-sex pairs, which were comparably harmonious across all tasks (Table IV). In-line with previous findings on the level of conflict, we observe a decrease in harmony in the first task in the all-female pairs, whereas in the remaining tasks the boys are noticeably more inharmonious.

6) Help: Noticeably, we identify a wide range of help sought by both same-sex pairs (p = 0.105). Overall, the all-female pairs sought more help than the all-male pairs (Table IV), which in particular is significant for task five (p = 0.023). Since this is the first task in which they implement own ideas, the all-female pairs might have needed guidance regarding the implementation [54], whereas the all-male pairs seemed to prefer to try it out for themselves.