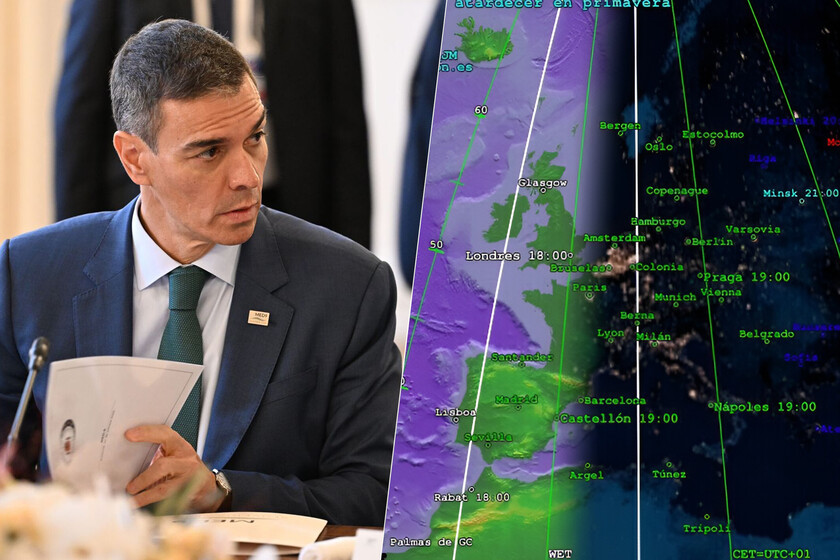

The week began with Pedro Sánchez announcing that “the Government of Spain will propose to the EU to end the seasonal time change.” Immediately afterwards, the marmorena got involved. And not because the idea does not have popular support: when in 2018 the European Commission Twitter.com/EU_Commission/status/1014814528582881280″>held his famous public consultation On the subject, 8 out of 10 people were in favor of ending it.

The problem is another and much more thorny: what schedule do we stick with?

The experts are clear about it. In fact, the consensus among specialists from the SES (Spanish Sleep Society) and many other international societies is surprising: science supports winter time. It is the time that (on paper) ensures better alignment with natural light, limits “social jet lag” and appears to consistently yield better health and safety results.

“Winter time makes it easier to have more hours of sleep and a more natural awakening that coincides with dawn. If there were a permanent summer time, in the winter months there would be a lack of light in the morning and in the summer months an excess of light at night, a situation that imbalances the internal clock and can cause poor performance and vulnerability to certain diseases,” the SES explained in its public positioning.

Martín Olalla, the great Spanish expert on these issues and a historical opponent of the elimination of seasonal time change, usually insists that the evidence makes it clear that the benefit is very limited. However, when choosing one of them, the winter one wins.

And then everything becomes strange. Because, although no one says it explicitly, in the popular imagination “permanent schedule” is associated with an “eternal pseudo-summer” full of long afternoons to comfortably enjoy the little leisure that day-to-day life leaves us. But let’s be honest, that’s not going to happen.

Daylight saving time has problems. The main one is that enjoying “long afternoons” throughout the year condemns the west of the peninsula to sunrises around ten in the morning. For landing it in a specific way. In A Coruña, in the middle of the winter solstice, it would dawn at 10:03 in the morning and set at 5:01 pm. Something that is, clearly, unfeasible.

A zero sum game. In the end, the seasonal time change is a compromise solution that tries to adjust the civil time to the variability of the days. It is probably a bad solution, but it helps mitigate the problems that would arise when opting for either of the other two schedules in a stable manner.

After all, with winter time Galicia, Asturias, Extremadura and western Andalusia would win; while they would lose the Mediterranean and the Balearic Islands. We would avoid very late mornings in winter and improve sleep, health and morning safety. The problem is that you kill the afternoons, which is the only socially attractive thing about making a permanent schedule.

And that “game” is not only regional. It is also economical. There are economic sectors such as tourism or hospitality, that prefer bright afternoons; but there are many others, such as school or industry, that prefer earlier sunrises.

Sometimes, phrases like “the time zone or time that corresponds to us” give the impression that the schedule is something ‘natural’: that the clock is neutral and all we have to do is adapt to it. But not. Nothing is neutral: opting for daylight saving time, winter time or daylight saving time is deeply political. Something that, whether we like it or not, prioritizes some over others.

It’s not a problem, what we have now does too.

The problem is another. It is walking towards the abolition of the time change without being aware of it and, above all, without being prepared for it: thinking that abolishing the time change will end all our chronoproblems is ‘magical thinking’. It will create others and, for the first time in more than a hundred years, we will not be able to blame it on the seasonal time change.

Image | Moncloa | Jon Tyson

In WorldOfSoftware | The war that ended at two different times: the time change has been giving Spaniards headaches for almost a century