Edison has been one of the most prolific inventors in history. In fact, while looking for a way to make the light bulb, he carried out an exhaustive materials science experiment: he tested more than 6,000 organic materials before settling on the carbonized bamboo filament. Pay attention to the old patent No. 223,898 because it has all the necessary ingredients for the recipe.

Tremendous Edison spoiler. He had, without knowing it, set up a primitive nanotechnological reactor to obtain graphene. That same graphene that Philip Russel Wallace would theorize about 20 years after the inventor’s death and 125 years before Konstantin Novoselov and Andre Geim won the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics for isolating it with the duct tape method. Or so a recent Rice University study has found.

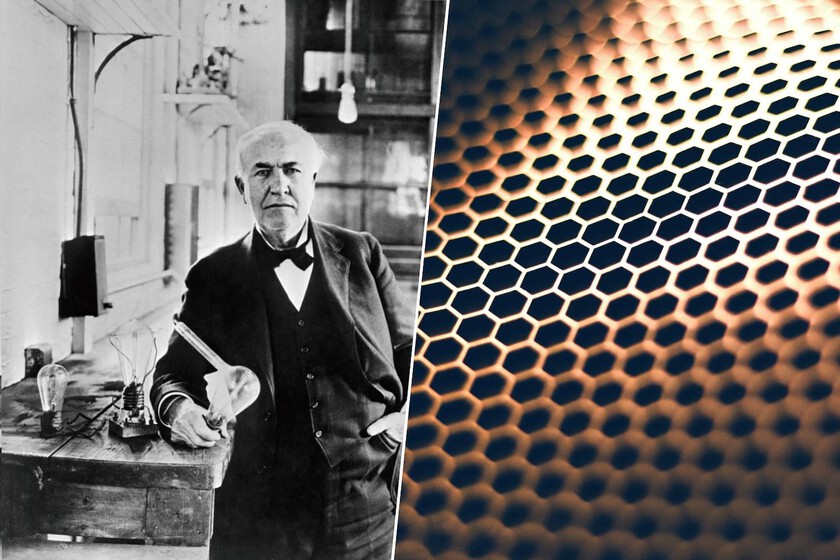

The prodigious graphene. Graphene is an allotrope of carbon that has a two-dimensional structure of atoms woven into a hexagonal network. Beyond this curiosity, graphene is an amazing material: it is 200 times stronger than steel but much lighter (airgraphene is even lighter than air). It conducts electricity and heat better than any known metal.

If we also take into account that it is almost transparent and very flexible, we have a prodigious material for technology. Without going any further, for semiconductors. It could also be used to improve roads or for sensitive robotic fabrics. And there’s a trick: when its layers are somewhat disordered and not stuck together like a block, they are much easier to separate. This is what Edison achieved unintentionally.

Edison’s recipe. Turbostratic graphene can be produced by applying a voltage to a carbon-based material until it reaches a temperature of 2,000 to 3,000 °C, known as instantaneous Joule heating. But what Edison had in his power was to light one of his newly patented light bulbs. Unlike the current ones, theirs had carbon-based filaments, more specifically bamboo. When you flipped the switch, the filament heated up and produced… light and maybe graphene.

Lucas Eddy, the lead author of the paper, says he was looking for ways to mass produce graphene with accessible and affordable materials and tried everything from arc welders to trees that had been struck by lightning. Then he remembered the light bulb. Edison’s patent was a magnificent scheme to reproduce the experiment. Of course, it was difficult for him to find Edison-style light bulbs with carbon filaments and not tugsten. Then he only had to apply power to 110 volts and turn on the switch for 20 seconds. If you go too far, graphite can form instead of graphene.

Why is it important. To begin with, because until now we thought that to obtain this prodigious material we had to resort to 21st century technology, but no: there were conditions to do so in the 19th century. On the other hand, it validates Joule heating as an efficient and scalable way to generate high-quality graphene from cheap carbon sources. And why not, because it opens the doors to reviewing other scientific experiments in history: who knows if other nanomaterials have not been synthesized by chance?

under the microscope. Using the lens of an optical microscope, the research team was able to see that the carbon filament had gone from dark gray to a shiny silver. A visual change that predicted the suspicions that were confirmed with Raman spectroscopy, which uses lasers to identify substances through their atoms with high precision: it was turbostratic graphene.

While Edison experimented to create a light bulb for everyday use he was able to produce the wonderful material of the future (of today’s future). Obviously there is no way to know for sure what happened in their Menlo Park laboratories because even if the original light bulb were available for analysis, any graphene produced would probably have converted to graphite within a few hours.

In WorldOfSoftware | Electrocute elephants to win a war or how anything went in the fight between Tesla and Edison

In WorldOfSoftware | Don’t call it graphene, call it “goldeno”: this is the new material that is achieved using a peculiar Japanese forging technique

Cover | Image of Thomas Edison, ca. 1918–1919. Source: National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), United States and HY ART