Hey Hackers!

This article is the first in a two-part series. I want to pull back the curtain on why Physical AI is one of the hardest engineering problems of our generation.

Most software engineers live in a deterministic world.

You write a function. You pass it an input. It returns the exact same output every single time. If it fails, you check the logs. You fix the logic. You redeploy. The server doesn’t care if it’s raining outside. The database doesn’t perform differently because the sun is at a low angle.

Physical AI does not have this luxury. It has to deal with the Body Problem of Artificial Intelligence.

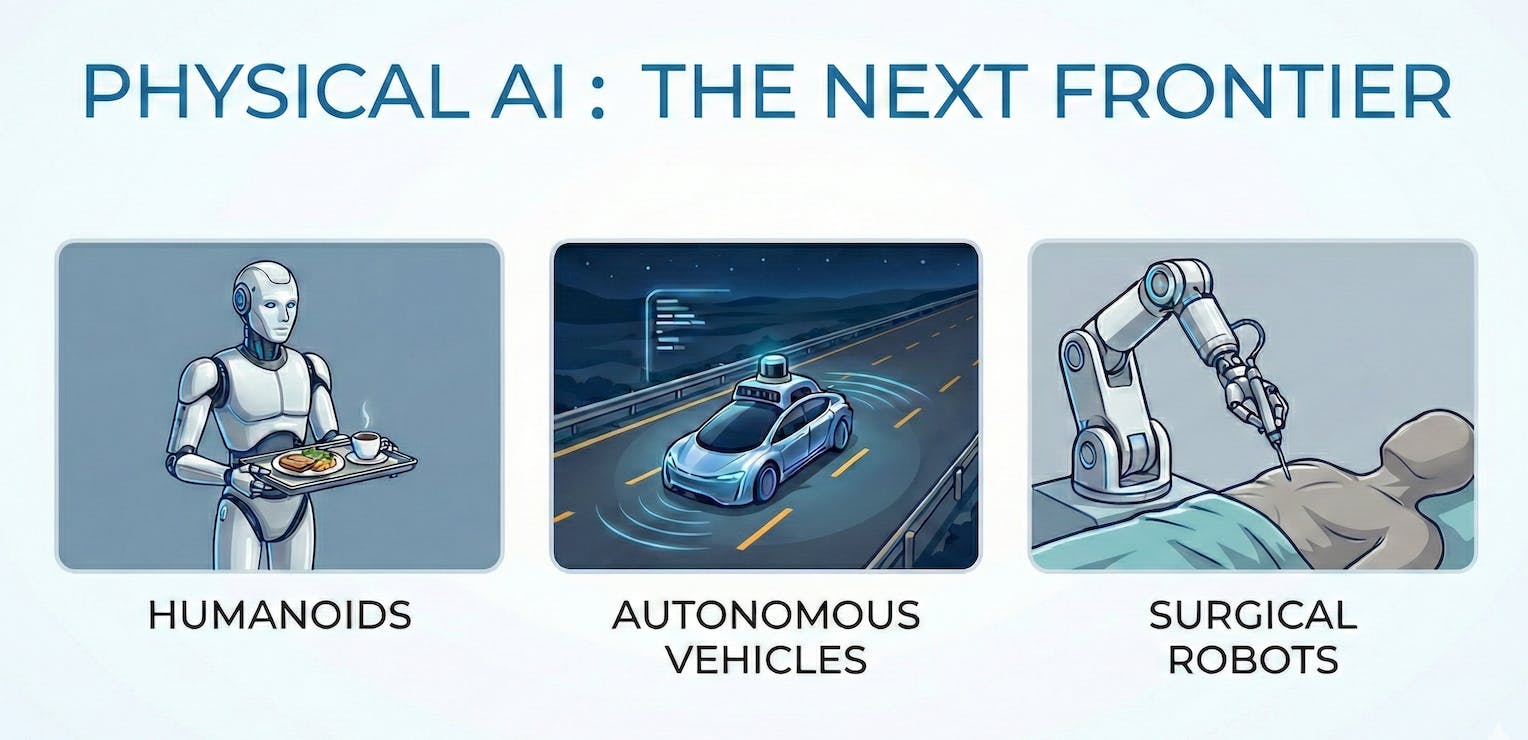

Today’s tech industry obsesses over Large Language Models generating text in data centers. Meanwhile, a quieter but much harder engineering challenge is playing out in the real world. It is happening on our streets with autonomous vehicles. It is playing out in operating rooms, where surgical robots assist with sub-millimeter precision. It is happening in warehouses, where robotic arms sort fragile packages next to heavy machinery.

This is the challenge of Physical AI. Research and industry communities sometimes also call this Embodied A,I which can be inferred as the science of giving an intelligent agent a physical body. I think it does not matter whether you call it Embodied or Physical because the engineering reality is the same. It is the discipline of taking neural networks out of the server and putting them into the chaos of reality.

When we build intelligence for these machines, we leave the clean world of logic gates. We enter the messy, probabilistic world of physics. A sensor might tell you a wall is ahead, but it might actually be a patch of fog or a reflection. The AI has to decide whether to stop or push through.

Why Listen to Me?

I’m Nishant Bhanot, and I help build these systems for a living.

My work has spanned the full spectrum of autonomy. At Ford, I worked on the core driver-assist technologies that keep millions of consumer vehicles safe on the highway every day. If your car has ever corrected your steering to prevent you from drifting out of your lane, or braked for you because a jogger with earphones suddenly ran in front of your car, you have felt the result of my validation work.

Today, I am a Senior Sensing Systems Engineer at Waymo. My work helps improve the fleet of thousands of fully autonomous vehicles across multiple major US cities like San Francisco, LA, Austin, Miami, and others. I spend my days solving the edge cases that arise when you deploy commercial robots at that scale.

I have learned the hard way that the physical world has a nasty habit of breaking even the most elegant algorithms.

The Input Problem of Data vs Intent

If you ask an LLM to write a poem, the input is simple. It is text. Maybe an image or video. A reference to a song at best.

Physical AI, however, requires a deep understanding of unsaid rules and physical properties.

Take, for example, an agricultural robot designed to pick strawberries. A standard vision model interprets a strawberry as just a red cluster of pixels. To a Physical AI, the same strawberry is a red and soft but somewhat pressurized object.

If the robot grips too hard, it crushes the fruit, but if it grips too loosely, it drops it. The AI cannot just see the berry. It has to feel the structural integrity of the object in real-time. It has to understand soft-body physics. This is a level of multimodal sensory processing that a text-generator never has to consider.

This nuance applies to social friction as well. A computer vision model can identify a car at an intersection, but the hard part is understanding why that car is creeping forward. Is the driver aggressive? Are they distracted? Or are they signaling a social contract that they want to turn right?

This applies to humanoid robots, too. If we want robots to cohabit with us, they cannot just track our location but rather read our micro-movements. A slight shift in a person’s shoulder might indicate they are about to stand up. If the robot doesn’t read that context, it creates a collision.

LLMs deal in tokens. Physical AI deals in social friction and intent.

The Consequence Gap Between Software AI and Physical AI

The biggest difference between Software AI and Physical AI is the cost of failure. This cost is driven by two invisible constraints. Physics and Time.

In standard software, a late answer is just an annoyance. If a chatbot takes three seconds to reply, it feels sluggish, but the answer is still correct.

In Physical AI, a correct-but-late answer is a wrong answer.

Imagine a reusable rocket attempting a vertical landing and is descending at 300 meters per second. If an AI guidance algorithm takes just 100 milliseconds to calculate the firing solution, the vehicle has fallen another 30 meters completely uncontrolled. It crashes into the pad before the engines can ever generate enough thrust to stop it. The physics of gravity do not pause while the software thinks.

We don’t just optimize for accuracy. We optimize for worst-case execution time. If the control cycle is 33 milliseconds, and the code takes 34, we don’t wait. We drop the frame. We have to. This need for speed is driven by the safety stakes.

I once experienced a complete blackout of the infotainment system in a rental car while driving at 70 mph. The screen went dark. The music stopped. It was annoying. I was frustrated. But the car kept driving. The brakes worked. The steering worked. The failure was confined to a screen.

I see a similar pattern with modern LLMs. I pay for high-end subscriptions to the best models available. Time and again, they provide me with “facts” that are sometimes unverified hallucinations. It is a waste of my time, and it breaks my workflow. But nobody gets hurt.

Physical AI does not provide this safety net. I can keep thinking of multiple scenarios where decisions of Physical AI bear consequences.

If a humanoid robot in your kitchen has a glitch, it doesn’t just display an error message. It drops your expensive china. It knocks over a boiling pot. I am pretty sure you would not want your robot butler to dart across the hallway at high speeds.

If an autonomous vehicle decides to drive the wrong way down a one-way street, it isn’t a bug, it is a significantly unsafe situation.

If a surgical robot’s vision system misinterprets a shadow and moves the scalpel three millimeters to the left, there is no undo button. It doesn’t throw an exception; rather, it unfortunately severs a nerve.

In the world of Software AI, a fix to a failure is a restart away. In the world of physical AI, fixing failures is most definitely not as simple as a restart. This fundamentally changes how we engineer these systems. We cannot afford to move fast and break things when the actions can lead to physical harm.

The Laboratory That Doesn’t Exist

Because the consequences of failure are so high, we face a paradox.

In almost every other discipline, you learn by doing. If you want to learn to ride a bike, you wobble and fall. If you want to test a new database schema, you run it and see if it breaks. Failure is part of the learning loop.

In Physical AI, learning by doing is rarely an option.

You cannot deploy untested code to a robotic arm handling radioactive waste just to see what happens. You cannot crash a billion-dollar satellite to teach it how to dock. We have to train these systems for the physical world without actually being in the physical world.

This forces us to rely on Digital Twins. We build physics-compliant simulations that replicate gravity, friction, light refraction, and material density. We have to build a Matrix for our machines.

But the simulation is never perfect. There is always a Sim-to-Real gap. A simulated floor is perfectly flat. A real warehouse floor has cracks, dust, and oil spots. If the AI overfits to the perfect simulation, it fails in the imperfect reality. We end up spending as much time validating the simulation as we do validating the AI itself.

The “99% Reliability” Trap

This brings us to the final hurdle of the Validation Cliff.

In web development, “Five Nines” (99.999%) of reliability refers to server uptime. If your server goes down for 5 minutes a year, you are a hero.

In Physical AI, 99% reliability is a disaster.

If a robot makes a correct decision 99 times out of 100, that means it fails once every 100 interactions. For a fleet of millions of personal humanoid robots making thousands of decisions per second, that error rate is mathematically unacceptable.

We have to validate for the “Long Tail.” We have to engineer for the weirdest, rarest events possible. The glare of the sun hits a camera at the exact wrong angle. A person wearing a T-shirt with a stop sign printed on it.

This is why Physical AI is the next great frontier. We have mastered the art of building models for processing information. Now we have to refine them such that they always exhibit safe physical behavior.

What Comes Next?

We have established that Physical AI is hard because the inputs are nuanced, time is scarce, and the stakes are fatal. But there is a bigger misconception holding the industry back.

There is a belief that to be safe, our robots should think and see like humans.

In Part 2, I will argue why this is a dangerous myth. I will explain why Human-Level accuracy is actually a failure state, and why the future of safety relies on machines that are decidedly superhuman. Stay Tuned!