Table of Links

Abstract

-

Introduction

1.1. Io as the main source of mass for the magnetosphere

1.2. Stability and variability of the Io torus system

1.3. Hypothesized volcanic mass supply events

1.4. Objective of this review

-

Review of the relevant components of the Io-Jupiter system

2.1. Volcanic activity: hot spots and plumes

2.2 Io’s bound atmosphere

2.3 Exosphere and atmospheric escape

2.4 Electrodynamic interaction, plasma-neutral collisions, and the related atmospheric loss processes

2.5. Neutrals from Io in Jupiter’s magnetosphere

2.6. Plasma torus and sheet, energetic particles

2.7 Jupiter’s aurora and connections to the Io torus

2.8 Dust from Io

-

Summary: What we know and what we do not know and 3.1 Current understanding for normal (stable) conditions

3.2 Canonical number for mass supply

3.3 Transient events in the plasma torus, neutral clouds and nebula, and aurora

3.4 Gaps in understanding, contradictions, and inconsistencies

-

Future observations and methods and 4.1 Spacecraft measurements

4.2 Remote Earth-based observations

4.3 Modeling efforts

Appendix, Acknowledgements, and References

1.2. Stability and variability of the Io torus system

The available data from the Voyager 1 and 2 flybys and continued ground-based observations, together with newly developed models, allowed more detailed characterization of the distribution, velocity and energy of the neutral and plasma environments. It was found that the loss processes from Io are likely driven by the interaction of the corotating plasma that overtakes Io at a relative speed of 57 km/s with a synodic period of 13 h (e.g., Saur et al., 2004). This suggests a positive feedback because increased loss from Io would enhance the plasma density in the torus, which in turn should enhance the loss rate through increased collisions between torus plasma and the atmosphere. However, the torus was found to be stable, evidenced mostly through neutral sodium cloud observations, which was the only part of the system that could be observed well from Earth at the time (e.g., Thomas, 1993). Therefore, a mechanism is required to limit the potential positive feedback. Schneider al. (1989) discusses different possibilities, including non-linear (exponential) loss of torus material with increasing torus density (Figure 1a), non-linear (e.g., logarithmic) supply to the torus from Io (Figure 1b) or linear dependencies but a steeper slope for the loss (Figure 1c). Several later studies suggest an increase in net radial transport in the torus with increasing torus density, thus supporting the supply-limiting hypothesis (e.g., Yang et al., 1994; Delamere et al., 2004; Hill, 2006; Hikida et al., 2020).

1.3. Hypothesized volcanic mass supply events

Strong enhancements in thermal emissions from Io were observed occasionally since 1978 and were dubbed ‘outbursts’ (see review by Spencer and Schneider, 1996). Such outbursts are now understood to represent extremely high effusion rates of high-temperature lava, often accompanied by large plumes of gas and dust (Davies, 1996). However, aperiodic or transient major changes in the environment or atmosphere had never been observed by 1996. Spencer and Schneider (1996) only speculate in their review: “As we improve our sensitivity to volcanic emissions, atmospheric abundances, and torus densities, we may identify the ways in which volcanoes modulate the Jovian system.” Two publications then essentially coined the idea that a volcanic event (like those seen in thermal outbursts) can trigger a transient change in the environment.

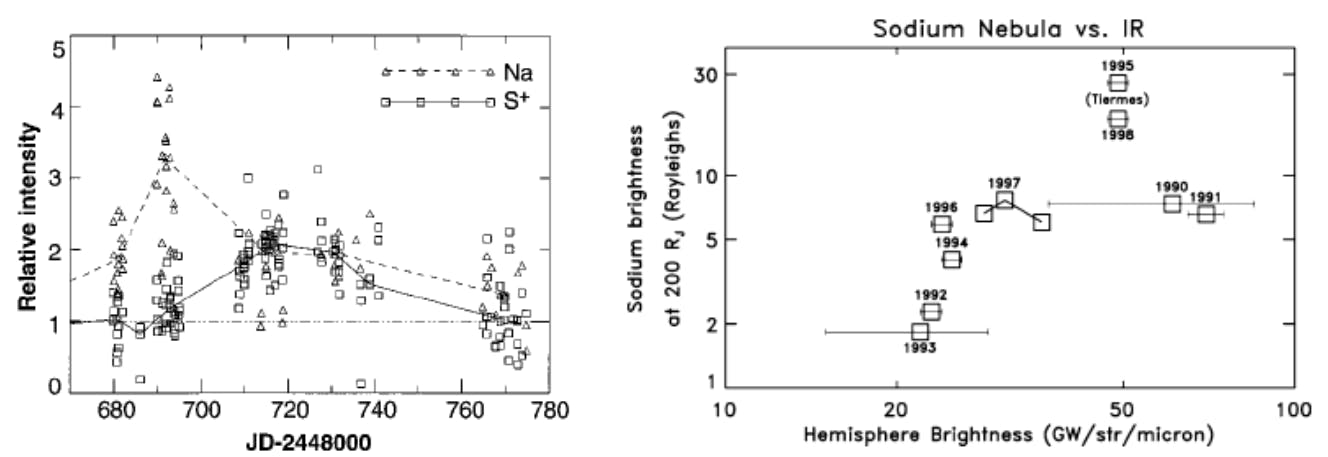

In the first of these, Brown and Bouchez (1997) detected a 4-fold increase in emissions from the sodium cloud followed by a 30% increase in sulfur ion emissions (Figure 2, left). The transient change lasted for about 70 days. The sodium was seen as an indicator for a change in mass supply from Io, which was assumed to be triggered by a volcanic outburst. The sulfur emissions reflect the state of the plasma torus, and the temporal curves were interpreted to be consistent with a loss-limiting scenario (Figure 1a).

The second key publication, Mendillo et al. (2004), reported long-term monitoring of the hot spot thermal emissions and the sodium nebula emission and found a putative correlation between the two parts (Figure 2, right), with the Loki volcano presumably playing a key role for the thermal increases. The authors interpret the results (although based on relatively few data with apparently some additional variability) as evidence for volcanic activity controlling the abundance of trace gas sodium, but are cautious about the effects on the bulk species (S and O).

After the studies of Brown and Bouchez (1997) and Mendillo et al. (2004), the narrative of a volcano-triggered transient change in the torus and magnetosphere (on time scales of weeks) was coined and many studies built upon these results to interpret their findings of transient events (e.g., Delamere et al., 2004; Yoneda et al., 2009; Bonfond et al., 2012).

A transient change in the torus in 2015, with a similar time scale of weeks, is the most well documented event to date thanks to the nearly continuous ultraviolet observations of the Hisaki satellite (Section 2.6). In addition to the observed transient change in the sulfur and oxygen ion emissions, Hisaki also measured for the first time an increase in the neutral oxygen emissions from Io’s orbital environment, simultaneously or marginally preceding the changes in ion emissions (Koga et al., 2018b; 2019). Enhancement in the sodium emissions (scattered sunlight) showed a common temporal envelope to that in the oxygen cloud (Yoneda et al., 2015). This affirms that the neutral cloud density was indeed elevated, as opposed to a brightening merely caused by increased torus electron impacts with neutral oxygen atoms. Some observations and modeling work had by this time indicated that the supply to the plasma torus comes from ionization of neutrals that had earlier escaped Io’s gravity, forming a cloud or complete orbital torus (Durrance et al., 1983; Skinner and Durrance, 1986; Bagenal et al., 1997; Saur et al., 2003). Whether the torus is sourced from these large scale neutral clouds orbiting Jupiter or by the localized ion pick-up at Io itself has been a major outstanding question (e.g., Thomas et al., 2004). The observation of a transient change in the neutral oxygen emission is consistent with the former: changes in the plasma torus are caused by (and preceded by) a change in neutral gas loss from Io to the larger scale neutral clouds (Koga et al., 2019). This 2015 event is discussed in detail in Section 2.6.

The change in total mass supply from Io that was inferred via modeling from the observed torus emissions is on the order of a factor 2 and up to 10 (e.g., Delamere et al., 2004; Koga et al., 2019; Hikida et al., 2020). Such changes are, however, difficult to reconcile with the current understanding of the exchange of mass (volatiles) between Io and its orbital environment. Furthermore, many of the often assumed correlations and connections between different parts of the system (like hot spots and volcanic plumes, or plume activity and mass supply to the torus) are unclear and not fully understood.

1.4. Objective of this review

This review aims to provide an overview of the current understanding of mass transfer from Io to the plasma torus and sheet, and the related phenomena in the Io-Jupiter system. In particular, our goal is to clarify the connections in the system and the limitations on the exchange of mass between Io’s surface and atmosphere and the magnetospheric environment. In Section 2, we review all the relevant parts of the system, focusing on their relation to the mass loss from Io and the supply of gas to Jupiter’s magnetosphere. Reviewing these parts, we discuss potential processes that could lead to events of short-term enhanced mass loss and their limitations. Section 3 summarizes the understanding of the system and addresses some contradictions and inconsistencies and discusses gaps in the current understanding of transient changes in the torus. We provide an overview of major transient events in the torus which were suggested to be related to an enhanced mass supply. Finally, in Section 4 we discuss prospects for future observations and modeling efforts that might help to improve our understanding of the supply of mass from Io, the environment and its short-term variability.

This review focuses on aspects related to the topic of Io as a source for the plasma torus. For a comprehensive review of all aspects around Io, we refer the reader to the recently published book “Io: A New View of Jupiter’s Moon” (eds. Lopes, de Kleer, and Keane, 2023).

Authors:

(1) L. Roth, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Space and Plasma Physics, Stockholm, Sweden and a Corresponding author;

(2) A. Blöcker, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Space and Plasma Physics, Stockholm, Sweden and Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany;

(3) K. de Kleer, Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125 USA;

(4) D. Goldstein, Dept. Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX USA;

(5) E. Lellouch, Laboratoire d’Etudes Spatiales et d’Instrumentation en Astrophysique (LESIA), Observatoire de Paris, Meudon, France;

(6) J. Saur, Institute of Geophysics and Meteorology, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany;

(7) C. Schmidt, Center for Space Physics, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA;

(8) D.F. Strobel, Departments of Earth & Planetary Science and Physics & Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA;

(9) C. Tao, National Institute of Information and Communications Technology, Koganei, Japan;

(10) F. Tsuchiya, Graduate School of Science, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan;

(11) V. Dols, Institute for Space Astrophysics and Planetology, National Institute for Astrophysics, Italy;

(12) H. Huybrighs, School of Cosmic Physics, DIAS Dunsink Observatory, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin 15, Ireland, Space and Planetary Science Center, Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, UAE and Department of Mathematics, Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, UAE;

(13) A. Mura, XX;

(14) J. R. Szalay, Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA;

(15) S. V. Badman, Department of Physics, Lancaster University, Lancaster, LA1 4YB, UK;

(16) I. de Pater, Department of Astronomy and Department of Earth & Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA;

(17) A.-C. Dott, Institute of Geophysics and Meteorology, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany;

(18) M. Kagitani, Graduate School of Science, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan;

(19) L. Klaiber, Physics Institute, University of Bern, 3012 Bern, Switzerland;

(20) R. Koga, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Aichi 464-8601, Japan;

(21) A. McEwen, Department of Astronomy and Department of Earth & Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA;

(22) Z. Milby, Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125 USA;

(23) K.D. Retherford, Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio, TX, USA and University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, USA;

(24) S. Schlegel, Institute of Geophysics and Meteorology, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany;

(25) N. Thomas, Physics Institute, University of Bern, 3012 Bern, Switzerland;

(26) W.L. Tseng, Department of Earth Sciences, National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan;

(27) A. Vorburger, Physics Institute, University of Bern, 3012 Bern, Switzerland.