Table of Links

Abstract and 1 Introduction

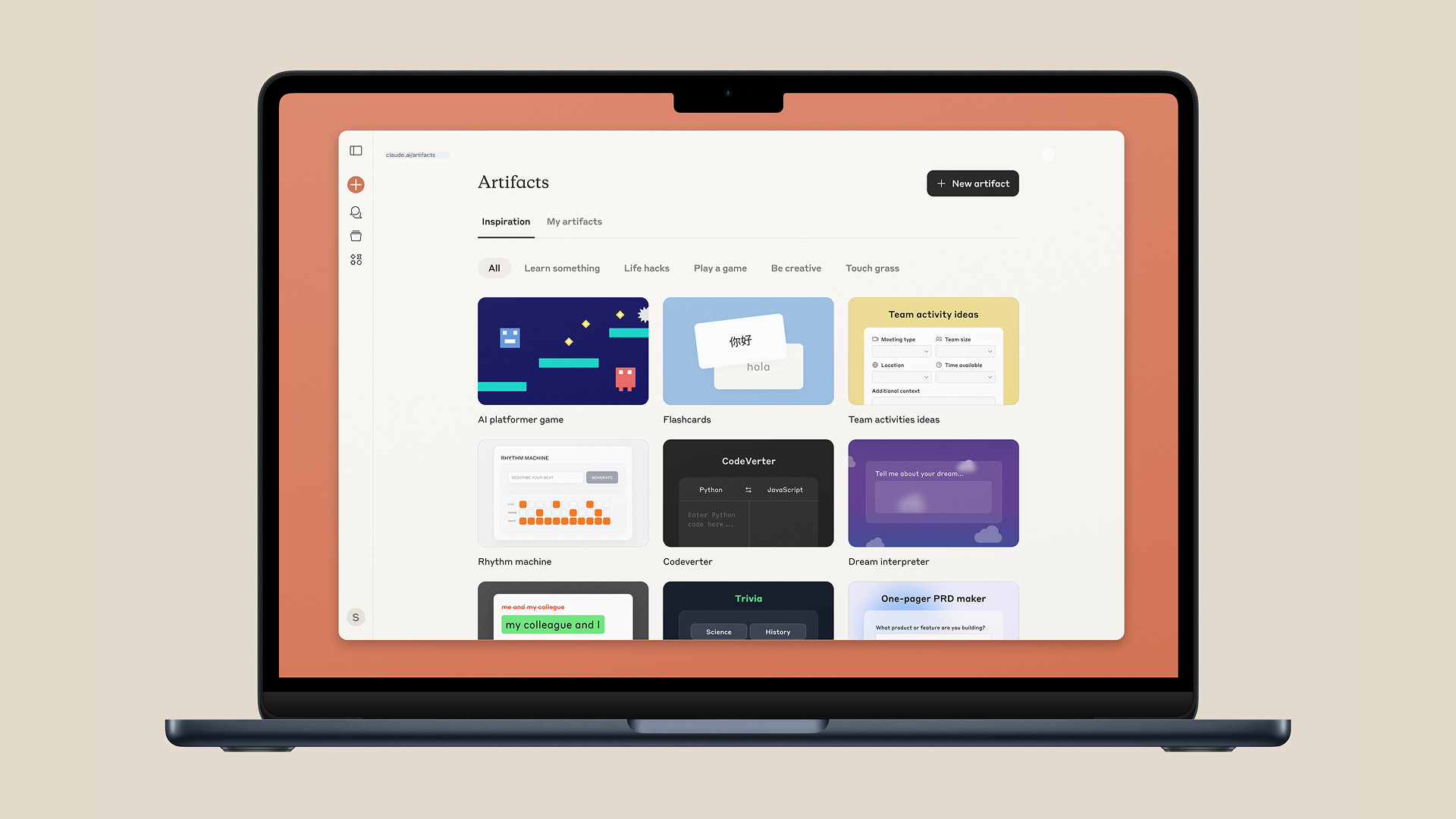

1.1 The twincode platform

1.2 Pilot Studies

1.3 Other Gender Identities and 1.4 Structure of the Paper

2 Related Work

3 Original Study (Seville Dec, 2021) and 3.1 Participants

3.2 Experiment Execution

3.3 Factors (Independent Variables)

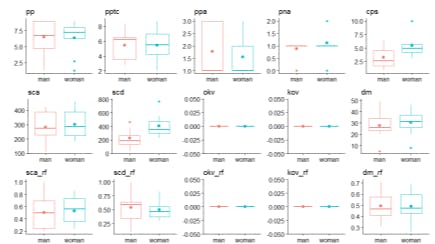

3.4 Response Variables (Dependent Variables)

3.5 Confounding Variables

3.6 Data Analysis

4 First Replication (Berkeley May, 2022)

4.1 Participants

4.2 Experiment Execution

4.3 Data Analysis

5 Discussion and Threats to Validity and 5.1 Operationalization of the Cause Construct — Treatment

5.2 Operationalization of the Effect Construct — Metrics

5.3 Sampling the Population — Participants

6 Conclusions and Future Work

6.1 Replication in Different Cultural Background

6.2 Using Chatbots as Partners and AI-based Utterance Coding

Datasets, Compliance with Ethical Standards, Acknowledgements, and References

A. Questionnaire #1 and #2 response items

B. Evolution of the twincode User Interface

C. User Interface of tag-a-chat

5 Discussion and Threats to Validity

In this section, the original study and its external replication are discussed. Since the main concerns are about their threats to the experimental validity regarding operationalization and sampling, the discussion is organized around these type of threats, especially those that were not previously discussed in the description of the replication changes in Sections 4.1 and 4.2.

5.1 Operationalization of the Cause Construct — Treatment

The operationalization of gender bias into a treatment is not a trivial task and, according to the obtained results, we may not have designed our treatment as adequately as we intended, thus threatening construct validity.

Considering our experimental design, telling the subjects that they were going to collaborate with a man or a woman more explicitly could have caused in many of them the suspicion of being observed about that fact, behave unnaturally and, probably, having mentioned it unintentionally during the chat messaging, thus discovering that they were being deceived about their partner’s gender and invalidating the study.

However, although the silhouetted avatars in the original experiment (see Figure 9(a)) had an effectiveness close to 60% (see Table 4), when they were changed in the replication into what we thought were more explicitly gendered avatars (see Figure 9(b)), their effectiveness dropped under 40% (see Table 6). Apart from the change of the avatars, this decrease in treatment effectiveness could have been probably affected by other factors, such as the remote setting, which increased the likelihood of distractions compared to a controlled environment such as a laboratory session, as commented in Section 4.2.2. Other factors could have been the reduced duration of the in-pair tasks and the second and third questionnaires, as previously discussed in Section 4.2.3, and the so-called Zoom burnout [49], i.e., the fatigue and exhaustion caused by prolonged use of video conferencing platforms during the COVID–19 pandemic, which may have influenced the motivation and performance of students at UC Berkeley, who are also exposed to very high levels of stress [41, 54].

As commented in Section 6.2, we are evaluating the use of chatbots together with a within-subjects design in future replications to improve the treatment and thus mitigate this threat to construct validity.

5.2 Operationalization of the Effect Construct — Metrics

The main goal of our work is exploring the effects of gender bias in remote pair programming. Due to this exploratory nature, we have applied methodological triangulation [13], observing the phenomenon from as many points of view as possible, with an operationalization based in 45 response variables of different types which were measured during a reasonable interaction time.

Having said that, during the coding of the chat utterances, some of the authors who are in their fifties at the moment of writing this article perceived strong differences in how the subjects, who are Generation Z youngsters [15], communicate compared to the way we did when we were their age. With all due caution, and taking into account the strong socio-political environment in Spain and the U.S. against any type of gender discrimination, we think it is possible that the presence of gender bias in people of our generation (Generation X) may have decreased two generations later, although we do not have enough evidence to affirm it. In addition, if gender bias persists, it is possible that most subjects self-censor, thus hindering the detection of its effects. To improve this situation, we are currently evolving the twincode platform to include more metrics, and we are also considering the inclusion of qualitative research that might lead to new findings in future replications by widening the spectrum of collected information.

5.3 Sampling the Population — Participants

5.3.1 Low Percentage of Women in the Original Study

Unfortunately, the small proportion of women in STEM studies is a common issue in most higher education institutions [1, 51]. The low number of women participants in the original study was an obstacle to study whether gender bias was mainly a masculine trait or if it was also present in women in any way. Nevertheless, the percentage of women increased substantially in the first replication without significant findings on the interaction of subject’s gender with other factors.

5.3.2 Small Size of the Sample in the Replication

The small size of the sample in the replication and the low effectiveness of the treatment supposed a clear threat to conclusion validity that can only be mitigated by taking the outcomes as provisional and performing more replications with bigger samples and alternative experimental designs in the future.

5.3.3 Using Students as Subjects

Although in other empirical studies in which subjects are Software Engineering students, findings can be reasonably generalized to a wider community because the experimental tasks do not usually require high levels of industrial experience [43], and the students, who are the next generation of professionals, are close to the population under study [19, 34, 45], the intergenerational differences commented in Section 5.2 and the lack of conclusive results makes that very difficult in our case.

Authors:

(1) Amador Duran, I3US Institute, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain and SCORE Lab, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain ([email protected]);

(2) Pablo Fernandez, I3US Institute, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain and SCORE Lab, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain ([email protected]);

(3) Beatriz Bernardez, I3US Institute, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain and SCORE Lab, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain ([email protected]);

(4) Nathaniel Weinman, Computer Science Division, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, USA ([email protected]);

(5) Aslıhan Akalın, Computer Science Division, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, USA ([email protected]);

(6) Armando Fox, Computer Science Division, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, USA ([email protected]).