Table of Links

Abstract/Zusammenfassung

Publications

Acknowledgements

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

-

Introduction

1.1 Overview of thesis contributions

1.2 Thesis outline

CHAPTER 2: BACKGROUND

2.1 Blockchains & smart contracts

2.2 Transaction prioritization norms

2.3 Transaction prioritization and contention transparency

2.4 Decentralized governance

2.5 Blockchain Scalability with Layer 2.0 Solutions

CHAPTER 3. TRANSACTION PRIORITIZATION NORMS

-

Transaction Prioritization Norms

3.1 Methodology

3.2 Analyzing norm adherence

3.3 Investigating norm violations

3.4 Dark-fee transactions

3.5 Concluding remarks

CHAPTER 4. TRANSACTION PRIORITIZATION AND CONTENTION TRANSPARENCY

-

Transaction Prioritization and Contention Transparency

4.1 Methodology

4.2 On contention transparency

4.3 On prioritization transparency

4.4 Concluding remarks

CHAPTER 5. DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE

-

Decentralized Governance

5.1 Methodology

5.2 Attacks on governance

5.3 Compound’s governance

5.4 Concluding remarks

CHAPTER 6. RELATED WORK

6.1 Transaction prioritization norms

6.2 Transaction prioritization and contention transparency

6.3 Decentralized governance

CHAPTER 7. DISCUSSION, LIMITATIONS & FUTURE WORK

7.1 Transaction ordering

7.2 Transaction transparency

7.3 Voting power distribution to amend smart contracts

Conclusion

Appendices

APPENDIX A: Additional Analysis of Transactions Prioritization Norms

APPENDIX B: Additional analysis of transactions prioritization and contention transparency

APPENDIX C: Additional Analysis of Distribution of Voting Power

Bibliography

In this chapter, we examine the literature relevant to this thesis. We explore three main topics: (i) transaction prioritization norms; (ii) transaction prioritization and contention transparency; and (iii) decentralized governance. The latter encompasses works that explore the distribution of decision-making power for blockchain governance.

6.1 Transaction prioritization norms

A few recent papers proposed solutions to enforce that transaction ordering follows a certain norm, mostly based on statistical tests of potential deviations (Asayag et al., 2018; Lev-Ari et al., 2020; Orda and Rottenstreich, 2019). These works were, however, mostly of theoretical nature in that they did not contain empirical evidence of deviation by miners, but rather assumed that miners might deviate. Prior efforts also proposed consensus algorithms to guarantee fair-transaction selection (Baird, 2016; Kelkar et al., 2020; Kursawe, 2020). Kelkar et al. (Kelkar et al., 2020) proposed a consensus property called transaction order-fairness and a new class of consensus protocols called Aequitas to establish fair-transaction ordering in addition to also providing consistency and liveness. A number of prior work focused on enabling miners to select transactions. For instance, SmartPool (Luu et al., 2017) gave transaction selection from mining pools back to the miners. Similarly, an improvement of Stratum, a well-used mining protocol, allows miners to select their desired transaction set through negotiation with a mining pool (Braiins, 2021b). All these prior work are, again, mostly of theoretical nature. In contrast, this thesis provides empirical evidence of deviation from the norm by miners in the current Bitcoin system.

Additionally, fairness issues have been studied in blockchain from the point of view of miners. Pass et al. (Pass and Shi, 2017) proposed a fair blockchain where transaction fees and block rewards are distributed fairly among miners, decreasing the variance of mining rewards. Other studies focused on the security issues showing that miners should not mine more blocks than their “fair share” (Eyal and Sirer, 2018) and that mining rewards payout is centralized in mining pools and therefore unfairly distributed among their miners (Romiti et al., 2019). Chen et al. (Chen et al., 2019) studied the allocation of block rewards on blockchains showing that Bitcoin’s allocation rule satisfies some properties. It does not, however, hold when miners are not risk-neutral, which is the case for Bitcoin. In contrast to these prior works, this thesis touches upon fairness issues from the viewpoint of transaction issuers and not miners.

There is a vast literature on incentives in mining. Most of it, however, considers only block rewards (Chen et al., 2019; Eyal and Sirer, 2018; Fiat et al., 2019; Goren and Spiegelman, 2019; Kiayias et al., 2016; Noda et al., 2020; Pass et al., 2017; Romiti et al., 2019; Sompolinsky and Zohar, 2015; Zhang and Preneel, 2019). As the block reward halves every four years in the Bitcoin blockchain, some recent work focused on analyzing how the incentives will change when transaction fees dominate the rewards. Carlsen et al. (Carlsten et al., 2016) showed that having only transaction fees as incentives will create instability. Tsabary and Eyal (Tsabary and Eyal, 2018) extended this result to more general cases including both block rewards and transaction fees. Easley et al. (Easley et al., 2019) proposed a general economic analysis of the system and its welfare with various types of rewards. Those prior works, however, assume that miners follow a certain norm for transaction selection and ordering (mostly the fee rate norm) and look at miners’ incentives in terms of how much compute power to exert and when (or some equivalent metric). There are also prior studies on the security issues of having transaction fees as the prime miners’ incentive (Carlsten et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018); and a vast literature on the security of blockchains more generally (e.g., (Gencer et al., 2018; Karame, 2016; Vasek et al., 2014)). Again, however, these studies focus on miners’ incentives to mine and not on transaction ordering; for the latter, they assume that miners follow a norm. These prior studies are, hence, somewhat orthogonal to this thesis.

Only a few recent works touched upon the issue of how miners select and order transactions, and how this is interlaced with how the fees are set. Lavi et al. (Lavi et al., 2019) and Basu et al. (Basu et al., 2019) highlighted the inefficiencies in the existing transaction fee-setting mechanisms and proposed alternatives. They showed that miners might not be trustworthy, but without providing empirical evidence. Siddiqui et al. (Siddiqui et al., 2020) showed through simulations that, with transaction fees only as incentives, miners would have to select transactions greedily, increasing the latency for most of the transactions. They proposed an alternative selection mechanism and performed numerical simulations on it. This thesis takes a complementary approach: We analyze empirical evidence of miners deviations from the transaction ordering norm in the current ecosystem. We also empirically analyze existing collusion at the level of transaction inclusion.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first of its kind—showing empirical evidence of norm violations in Bitcoin—and our results help motivate the theoretical studies mentioned above.

6.2 Transaction prioritization and contention transparency

As previously mentioned, recent work analyzed the implications of relying on transaction fees separately (Carlsten et al., 2016) and in conjunction with block rewards (Tsabary and Eyal, 2018), as well as the relationship between such incentives and transaction waiting times (Easley et al., 2019). These prior works assume that transactions are broadcast to all miners and the fees offered is uniform across miners. None of them acknowledge the issue of transparency. Prior work also analyzed the Ethereum fee (i.e., gas price) mechanism to determine the gas price for a given transaction (Antonio Pierro et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Mars et al., 2021; Turksonmez et al., 2021). However, the fee estimation and fee-based prioritization schemes in these studies do not take into account dark-fees or private mining.

Many transaction-accelerator, or front-running as a service (FRaaS), platforms exist for both Bitcoin (BTC.com, 2022; ViaBTC, 2022) and Ethereum (Eskandari et al., 2020; Flashbots, 2022b; SparkPool, 2021). Transaction issuers might resort to such acceleration or off-chain payment channels to hide their true fee from competitors and avoid being front-run (Daian et al., 2020; Strehle and Ante, 2020). Tim Roughgarden (Roughgarden, 2021) discussed the incentives for off-chain agreements (such as dark-fees) between miners and users for first-price auctions and different deviations of the new Ethereum fee mechanism EIP-1559 protocol (Buterin et al., 2019a). Roughgarden showed that miners and users cannot strictly increase their joint utility through off-chain payments under EIP-1559 because on-chain bids can be easily replaced by the off-chain bids. However, utility here is only based on the revenue of bidding for block space. The author did not take into account that utility might depend on other factors, such as transaction issuers wanting to keep their actual bids for block space hidden through off-chain payments, which strictly increases their chances of prioritization, as other bidders cannot counter bid, as they are unaware of the bid itself.

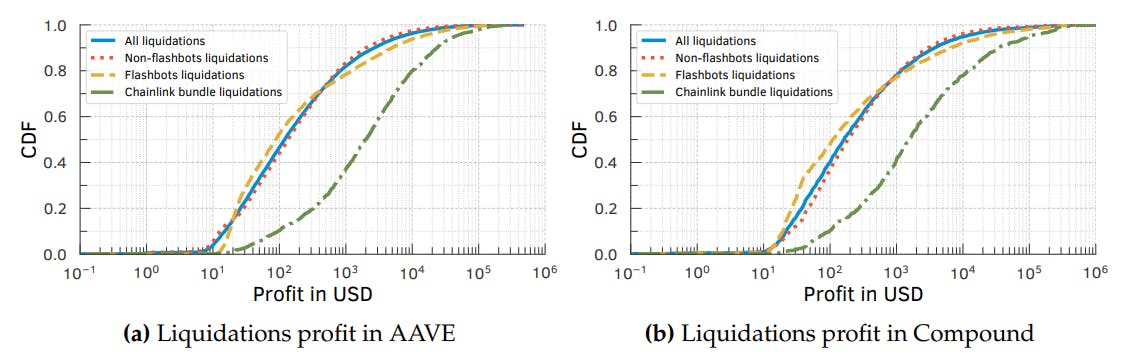

There are two work that analyze private mining. Strehe and Ante (Strehle and Ante, 2020) investigated exclusive mining (or private mining), where transactions issuers and miners collude to include transactions that have been sent through a private network. In this case, the transactions are not publicly disclosed until they have been included in a block; besides, the fees can remain opaque to everyone forever, as such off-chain agreements may use fiat currencies. Weintraub et al. (Weintraub et al., 2022) measured the popularity of Flashbots, the most used private relay network for Ethereum. This thesis, in contrast, extensively investigates private transactions and dark-fees in the context of Bitcoin and Ethereum blockchains. Through active measurements, we empirically show that Bitcoin miners collude and highlight the colluding mining pools. We show that Flashbots bundles are quite prevalent in Ethereum and are mainly used for calling Decentralized Exchanges (DEX) contracts to take advantage of Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) opportunities. Finally, we discuss why our findings are still valid after “The Merge”—an Ethereum hard fork deployed on September 15th, 2022 (Ethereum Foundation, 2022a,b).

Author:

(1) Johnnatan Messias Peixoto Afonso