Have you ever wondered why some products just feel right, perfectly integrated, even when they’re made of many different parts? Or why a seemingly simple design can be a powerful competitive weapon? A fascinating study by Sheen S. Levine and Johannes M. Pennings, titled “What You See is not What You Get: Product Architecture and Corporate Strategy,” delves into these very questions, revealing that product design is far more than just an engineering feat; it’s a critical strategic decision that impacts everything from firm performance to consumer perception.

This research, drawing insights from technology, operations, and organizational theory, explores how decisions about product architecture — the composition and interdependency of components that make a product — are not solely the domain of engineers. Instead, factors like firm prestige and customer sophistication play a significant role.

Understanding Product Architecture: Beyond the Blueprint

Before diving into the strategic implications, let’s understand what product architecture truly means. The literature identifies four core archetypes that can describe almost any product: integral, slot, bus, and sectional. These archetypes differ based on how components relate to each other and their degree of interdependency.

Integral Design: Think of a disposable ballpoint pen. All its components fit tightly and idiosyncratically, making the product self-contained and tightly coupled. This design can simplify manufacturing and presents a neatly packaged product to the consumer, also making it tough for competitors to offer after-market additions. However, its biggest drawback is its resistance to change; even a minor alteration in one component can necessitate reviewing and changing all others. Organizationally, this tight coupling has repercussions for how people inside and outside the firm align their activities, as interdependencies need constant coordination.

Bus Design: In a bus design, components connect to a central interface rather than directly to each other. A great example is a desktop computer, where you can swap a hard drive for a DVD drive because both connect to the same “bus”. Similarly, speakers can be changed on a stereo amplifier as long as they feature the same interface. This design offers greater flexibility for customization. While not entirely modular, components must feature a specific interface to connect to the system.

Sectional Design: This archetype represents complete modularity, allowing components to be added or removed freely, much like Lego bricks. A modular shelving system is a good illustration, accommodating various lengths, widths, or stacks of drawers.

While few products fit purely into one category, understanding these archetypes is crucial for analytical purposes. Traditionally, discussions on product architecture have maintained a strong engineering focus, concentrating on function, cost, manufacturing, and servicing. However, this study suggests that a broader view, incorporating strategic and organizational considerations like product differentiation, yields new insights.

The “What You See is Not What You Get” Phenomenon: Janus-Faced Design

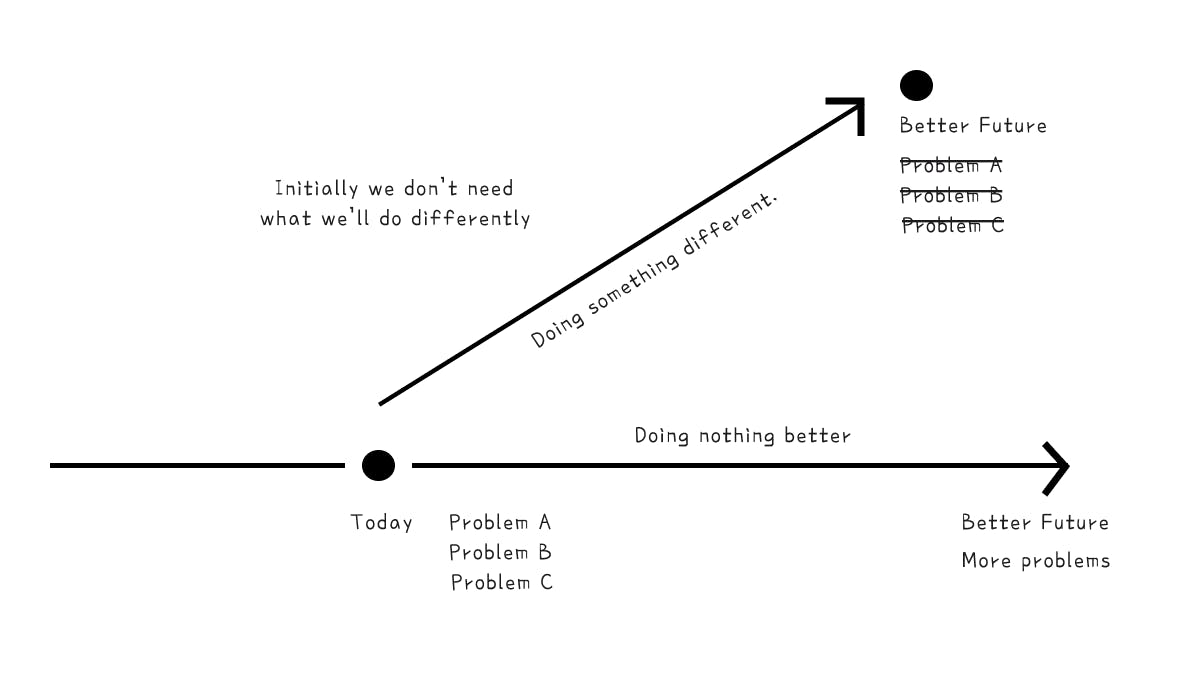

One of the most profound insights of this research is the idea that product design can have important competitive consequences. Specifically, the study introduces the concept of Janus-faced product architecture, named after the Roman deity with two contrasting faces. This describes products that appear to have an integral design to consumers, while their engineering reality is based on a bus or sectional design.

The iPod Paradox: Integral Perception, Modular Reality The Apple iPod is a prime example of this phenomenon. Despite being hailed as innovative and a breakthrough offering, and even transforming Apple into a consumer electronics giant, a close inspection reveals that almost none of its components are produced or even designed by Apple. Its processor, operating software, hard disk, battery, and display are all sourced from various suppliers like Portal Player, Pixo, Toshiba, Sony, and LG. One of the few components Apple designed was the FireWire bus, which manages data transfer between these disparate parts.

So, why do consumers perceive this collection of outsourced, bus-designed components as “sleek,” “elegant,” and a culturally transforming invention? The study posits that while the iPod is architecturally based on bus design, it is perceived as having an integral design. This leads to a key hypothesis: the perception of product architecture can be decoupled from its engineering architecture. Achieving this decoupling is significant because a firm’s ability to infuse its products with an integral identity relies heavily on the seamlessness of both internal and external structures. If the relationships between component makers are not seamless, consumers are likely to perceive deficiencies.

Camera Industry Insights: Different Designs for Similar Products The research also examines the camera industry to demonstrate how similar products can feature markedly different product architectures. Every camera fundamentally consists of a lens, a capturing device (film or digital), and an enclosure.

- Point-and-shoot cameras exemplify integral design, bundling all elements in a single unit where the lens cannot be replaced independently.

- Single-lens reflex (SLR) cameras showcase bus design. Here, the lens is decoupled from the body (which contains the capturing device), allowing consumers to choose from various lenses that connect via an electronic bus.

- Professional-grade cameras (medium- and large-format) demonstrate sectional architecture, allowing users to freely swap and match lenses, capturing media, and camera bodies.

These examples highlight that firms have a strategic “decision space” to determine how a product should be engineered and how it should be communicated to consumers.

Who Chooses What? Consumer Preferences and Firm Status

Beyond engineering considerations, two major factors influence product architecture decisions: consumer preferences and firm status.

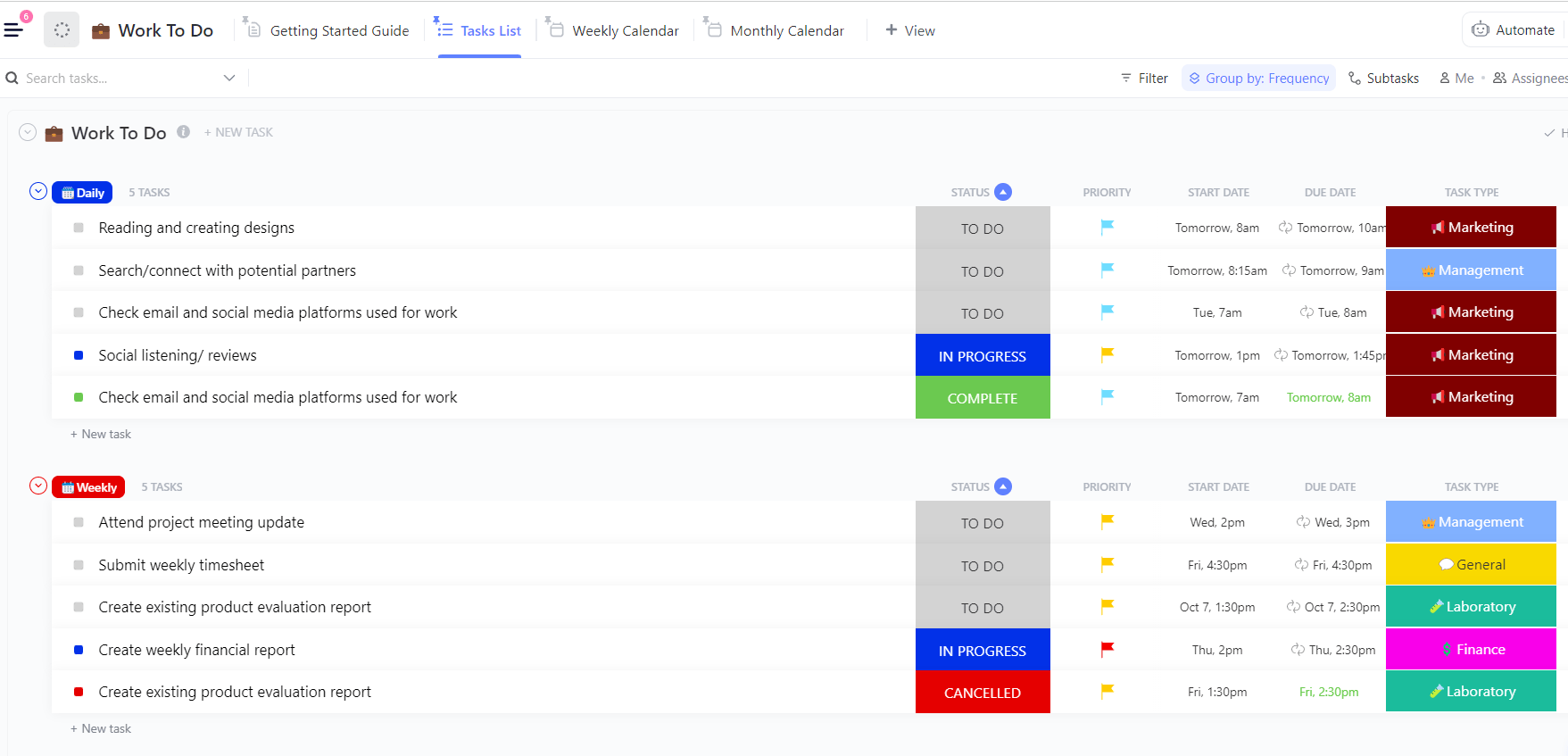

Sophistication Matters: Matching Design to Consumers Different consumer groups prefer different architectural designs based on their level of sophistication.

- Lay consumers (naïve and unsophisticated) tend to gravitate towards the simple, neatly packaged products of integral design.

- Hobbyists and professionals (sophisticated consumers) prefer the flexibility and customization possibilities associated with bus and sectional designs.

This leads to two hypotheses:

- H2a: The less sophisticated a consumer segment is, the greater their preference for product architecture closer to integral design.

- H2b: The more sophisticated a consumer segment is, the greater their preference for product architecture closer to sectional design.

The Prestige Factor: How Status Shapes Product Strategy Firm status also plays a crucial role. High-status firms, due to their prestige, can produce more cheaply and charge premium prices, while low-status firms face disadvantages. High-status firms also seek to avoid “status leakage” by limiting interactions with lower-status firms, while low-status firms actively seek such associations.

Applying this logic, the study hypothesizes:

- The higher a firm’s prestige, the greater its ability to achieve a high degree of architectural integration with a strong sense of product unity.

- High-status firms will strive to create a perception of integral design, even if their product is bus or sectional (like the iPod).

- Low-status firms, seeking association with higher-status firms (e.g., by including their components), will gravitate towards bus or sectional design.

This suggests that combinations like “low firm status-integral design” and “high firm status-sectional design” are strategically undesirable. The research posits two further hypotheses regarding performance:

- H3a: When facing lay consumers and having high status, a firm will perform better by gravitating towards integral design.

- H3b: When facing sophisticated consumers and having low status, a firm will perform better by gravitating towards sectional design.

The Strategic Matrix: Navigating Choices The research summarizes these interactions in a matrix (Table 2 in the source), indicating optimal strategic positions based on firm status and target consumer sophistication. For instance, a high-status firm targeting lay consumers would aim for a “sectional integral” approach (engineering bus/sectional, perceived integral), while a low-status firm targeting sophisticated consumers would lean towards sectional design.

The Paradox Unveiled A profound paradox emerges from these observations. While sophisticated customers prefer sectional designs, and high-status firms (who often target these customers) lean towards bus or sectional architectures, lay consumers prefer integral designs, yet low-status firms catering to them often lean towards integral architectures. This suggests that high-status firms face barriers in “opening their innovation” towards their most knowledgeable customer segments.

Strategic Insights and Future Directions

The implications for firms are significant. As industries become more modular (e.g., photographic sector), firms’ “make or buy” decisions increasingly require accumulating social capital and forming alliances with high-status partners. This helps high-status firms guard their integrity and avoid status leakage. For example, photographic equipment manufacturers would benefit from partnering with component suppliers (like lenses, flashes, CCDs) that have matching status. The study notes that large price differences exist for components based on their branding.

The research also highlights that insourcing and outsourcing are prevalent in the photographic sector, even more so than in vehicle manufacturing or computing. While the governance of these inter-firm relationships and their mapping onto product architecture remain areas for further study, early evidence suggests that insourcing is becoming a dominant form of organizing for both component design and manufacturing.

Comparing with vehicle manufacturers like Toyota, Nissan, and Honda, the study notes variations in how they coordinate and transfer knowledge to outsourcing partners. Toyota, for instance, is more aggressive in transferring tacit knowledge, ensuring greater seamlessness in its components.

The study proposes several key propositions derived from its arguments:

- In sectors undergoing paradigm shifts, the status legacy of incumbent firms carries forward even after disruptive technologies replace established ones.

- Status acts as a major complementary asset that incumbent firms leverage during technological transitions.

- High-status firms have a bargaining advantage when partnering with firms possessing complementary assets compared to their low-status peers.

- An incongruence exists between sectional versus integral product-market focus, stemming from customer sophistication and producer status.

- High-status firms produce modular equipment whose architecture suggests an integral configuration.

- High-status firms form close, embedded alliances with high-status partners, while low-status firms maintain arm’s-length relationships with suppliers.

- High-status firms engage in “evolutionary capability” (capability for capability building) with their insourcing partners, while low-status firms resort to a more basic “maintenance capability” (ability to maintain performance consistency).

A Glimpse Behind the Research: Methodology

This research adopted a qualitative approach, which is particularly suitable for developing theory inductively, especially when uncovering meaning, process, context, and unanticipated phenomena. The researchers used a maximum variation sampling technique, choosing diverse sites (multiple industry sectors, countries, and hierarchical ranks) to generate rules about variable relationships. Data was collected through dozens of open-ended, moderately directive interviews, repeated interviews, document analysis, observations, and informal conversations over five months, primarily focusing on the photographic equipment and mobile music player industries. The data analysis followed established grounded theory methods, involving continuous coding and refinement of categories. Findings were validated by presenting them to informants and industry experts.

Conclusion

The study “What You See is not What You Get” offers a compelling argument that product architecture decisions are deeply intertwined with corporate strategy, consumer perception, and firm status. It challenges the traditional engineering-centric view, revealing that the strategic decoupling of perceived and engineering design, as exemplified by the iPod, can be a source of significant competitive advantage. As industries continue to evolve and modularity increases, understanding these intricate relationships will be crucial for firms aiming to achieve sustained performance and innovation.