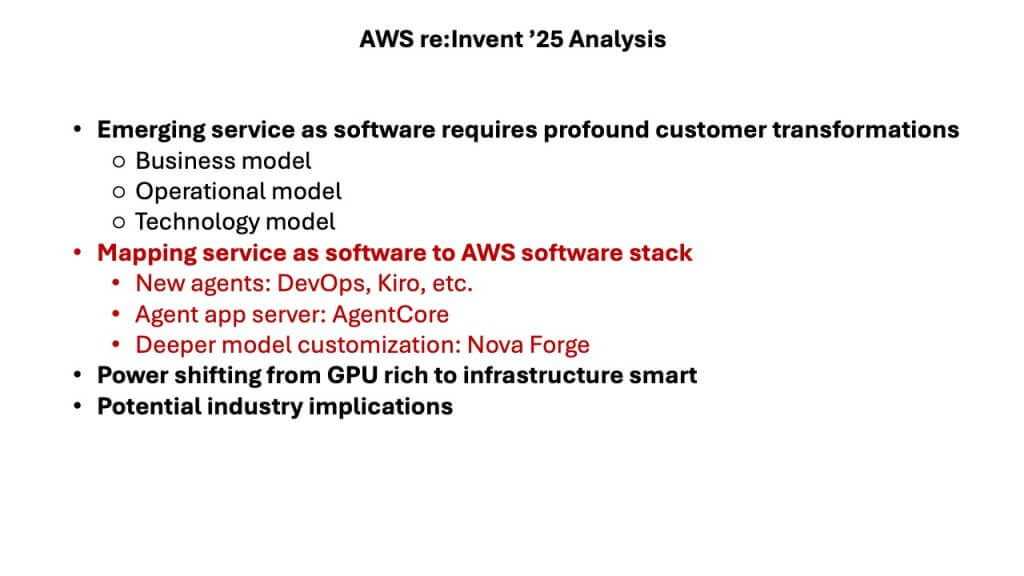

At AWS re:Invent 2025, Amazon Web Services Inc. faced a dual mandate: Speak to millions of longstanding cloud customers while countering a persistent narrative that the company is lagging in artificial intelligence. In our view, AWS chose a distinctly pragmatic path.

Rather than chasing the holy grail of what we call “messiah AGI,” or artificial general intelligence or even competing head-on with frontier-scale large language model, the company emphasized foundational agentic scaffolding and customizable large and small language models. This approach aligns with our thesis that the real near-term value in AI lies inside the enterprise – what we see as “worker-bee AGI” – not in aspirational, generalized intelligence.

Skeptics argue that this worker-bee AGI is little more than RPA 2.0, burdened by familiar data silos. Though that critique rings somewhat true, we not view AWS’ strategy as merely paving the robotic process automation cow path. Rather, we see the company making a deliberate shift from siloed agentic automation toward what we call “service-as-software” – a new model in which business outcomes, not individual applications, become the primary point of control.

In this special edition of Breaking Analysis, we break down AWS re:Invent 2025 through the lens of this emerging paradigm. We’ll examine how AWS is repositioning its infrastructure, services and AI roadmap to support a transformation in the operational, business and technology models of virtually every organization and industry.

Why enterprise worker-bee AGI is where the real money will be made

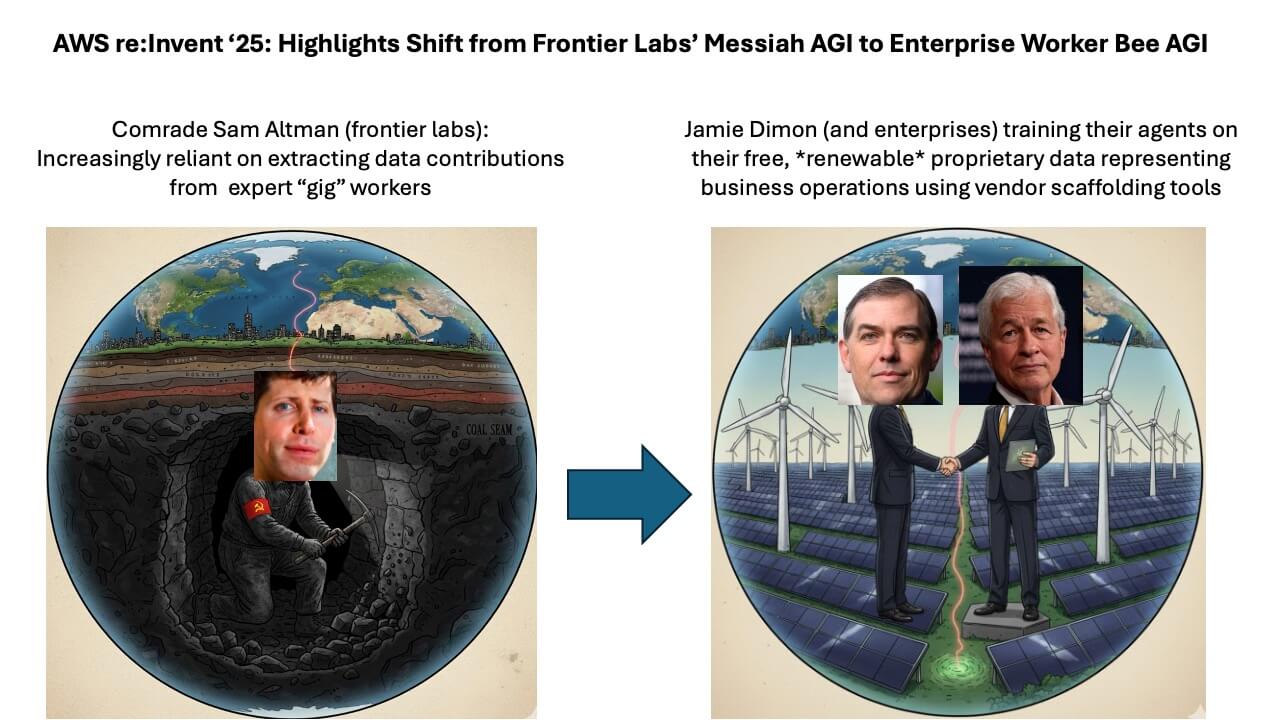

Key messages in the title slide

At re:Invent 2025, one theme kept surfacing in our conversations in that we’re watching two fundamentally different AI models collide. On one side, we see what we call the messiah AGI quest – led by Open AI Labs PBC Chief Executive Sam Altman and the frontier labs – pushing ever deeper into the earth in search of more intelligence. On the other side sits the enterprise, represented metaphorically by JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon and powered by renewable, sustainable data assets that grow stronger with every additional agent deployed.

OpenAI and ChatGPT defined the opening chapter of generative AI by tapping a reservoir of free, high-quality internet data. Through GPT-4 and likely GPT-5, the marginal cost of data was essentially zero. Compute was expensive, but the fuel for the models was essentially free. That era is ending, in our view. As freely available high-quality data is depleted, the labs are turning to human expertise – curated reasoning traces from domain specialists – to maintain their performance advantage. We see this as a dramatically different business model.

Credible reporting suggests that by 2029 to 2030, OpenAI could be spending 20% to 25% of its revenue just to acquire proprietary expert data. In our view, this is a classic diminishing-returns scenario where you achieve rising marginal costs for increasingly niche improvements. It’s the image of Altman digging deeper into the ground for shrinking seams of coal.

Enterprises, by contrast, operate on renewable energy, as shown on the right hand side of the title slide. Their proprietary data grows as they deploy more agents, build more models and instrument more workflows. Every incremental deployment generates more signals, more context, more labeled outcomes. They’re on an experience curve – one that accelerates as data harmonization improves. JPMorgan Chase is the most obvious example, but it represents a much broader pattern. The more enterprises connect their systems of record with their emerging agent ecosystems, the faster their marginal costs fall.

This is why we believe the real economic opportunity lies with worker-bee AGI inside the enterprise, not messiah AGI in the labs.

The image of windmills and solar farms on our cover slide symbolizes the renewable nature of enterprise data. In the age of AI, algorithms are increasingly commoditized and developed by specialized labs. But shaping data – aligning it with workflows, policies, context and outcomes – is where competitive advantage resides.

This brings us to a critical question: Could OpenAI simply partner with leading enterprises to overcome its data disadvantage? In theory, yes. In practice, we see three barriers:

- Data sovereignty and trust: Frontier labs require data to be moved into their environment. Enterprises must hand over their crown jewels. By contrast, open-model, open-weight approaches (like AWS is taking) allow companies to bring weights and partially trained models into their virtual private clouds without exposing sensitive information.

- Agent scaffolding: Making agents operational inside business workflows requires deep scaffolding – both developer tools and data infrastructure. Even OpenAI acknowledged its agent tools lag behind Databricks Inc. And Databricks itself lacks the full system-of-intelligence scaffolding needed to integrate agents with legacy deterministic workflows.

- Enterprise software depth: Turning decades of enterprise applications into agent-compatible scaffolding is a monumental undertaking. We believe this is a sustaining innovation for enterprise independent software vendors – not a domain frontier labs can overtake quickly.

In other words, owning a frontier model isn’t enough. To win in the enterprise, the model must be embedded in the workflow to include policy, security, data lineage, context, orchestration, and deterministic logic. This is software, not science, and thus far frontier labs are not enterprise software companies.

(Note: Our colleague David Floyer disputes this premise. He believes research labs such as OpenAI and Anthropic will build great enterprise software on top of their LLMs and simplify the adoption of enterprise AI. We’ll be digging into and debating this topic with him in future Breaking Analysis episodes.)

As a result, the disruption won’t manifest in the technology model alone, rather we’ll see it in the operational and business models of emerging AI software companies – including pricing. The seat-based pricing model that has defined enterprise software for decades will not survive the agentic era, in our view. Infrastructure consumption models will evolve as well. We believe the winners will shift toward value-based/outcome-based pricing aligned with real business results.

This is the heart of service-as-software. And AWS – whether intentionally or instinctively – is leaning directly into this shift. It is missing some pieces, however, which we’ll discuss in detail.

Agenda for this Breaking Analysis

Operational, business and technology models reset for the agentic era

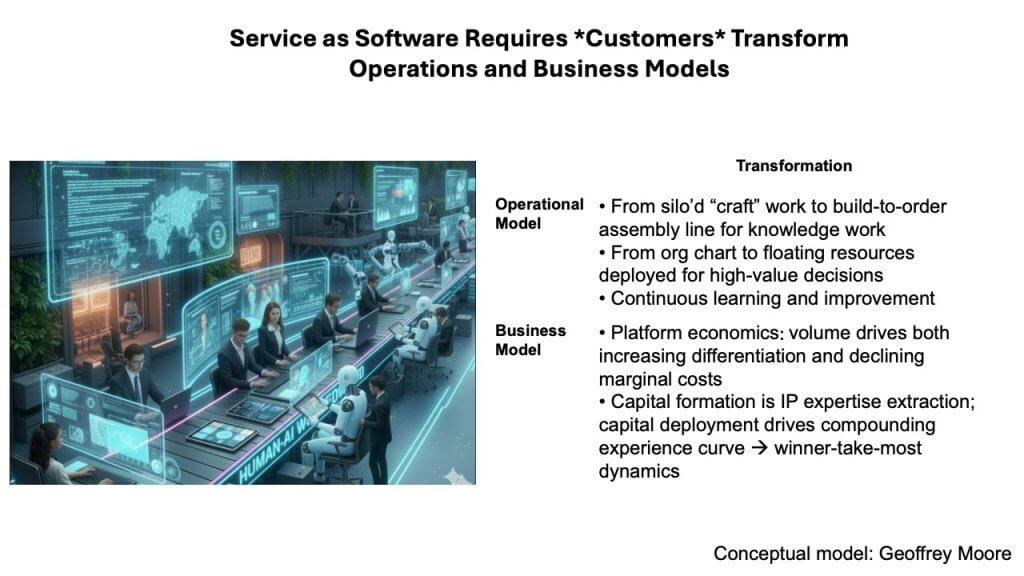

Let’s park the technology model for a moment and examine the coming changes in the operational and business models of enterprises as a result of AI.

As we’ve argued in earlier Breaking Analysis episodes, the shift to AI-driven operations requires a wholesale transformation of how organizations function – not just in their technology stacks, but in their operational and business models. When the industry migrated from on-premises software to software as a service, the burden fell largely on information technology departments and software vendors. Mainstream organizations didn’t have to rethink how their companies worked. This time is different in that the entire organization will change.

Practitioners often say the hard part of transformation is people and process, not technology. In the agentic era, all three are hard. The operational model, the business model and the technology model must move in concert, and none of them can remain anchored in legacy assumptions.

For six decades – despite new devices, new user interfaces and new software delivery models – the industry continued to build in silos. These were essentially craft cells for knowledge work, each optimized locally because that was the only way we knew how to automate. The shift ahead replaces these craft silos with an end-to-end assembly line for knowledge work. That represents a profound process change. The organizational structures built to make machine-like efficiency possible no longer align with end-to-end outcomes.

On the business model side, the shift is equally profound. Traditional software economics were built around nonrecurring engineering or NRE costs. Pricing was often seat-based with added maintenance fees, and steadily improving (and predictable) marginal costs as volume grew. Even in the cloud era, despite variable infrastructure costs, vendors benefited from the same model – upfront NRE, light ongoing maintenance and falling marginal costs as scale increased.

AI breaks that pattern.

In the new model, organizations deliver outcomes, and pricing will be based on value, usage or direct outcome proxies. More important, the foundation of economic advantage shifts from physical capital and depreciating software assets to digital expertise that compounds. Intelligence becomes capital. The more data that flows through the system, the richer the experience base becomes. Cost advantages and differentiation strengthen simultaneously, creating winner-take-most dynamics.

This is where tokens enter the equation. Software companies not only face cloud cost-of-goods-sold, they now incur token costs. Though consumers may benefit from improvements in graphics processing unit price-performance, the marginal economics that once accrued to software vendors increasingly accrue to the organizations that climb the AI learning curve fastest. Getting volume and getting there fast becomes critical; once a company builds compounding advantage through expertise, it becomes extremely difficult for others to catch up.

This gets back to the difference between models and agents. The model guys are in this “token grind” where through distillation and advances in the frontier of intelligence, their costs are coming down something like 10 to 30 times per year, some obscene number when it’s just the raw model and the application programming interface.

But when it’s an agent and there’s a learning loop in there, their prices are much more stable. And so that gets back to what we’re going to talk about, and where AWS is focused, which is the surrounding scaffolding needed to build, manage and govern agents.

The bottom line is the economics of software are being rewritten. Depreciating assets are giving way to compounding expertise, and organizations that build these systems early will gain durable structural advantage. In our view, this shift underpins the emerging service-as-software model – and explains why enterprise AI will look nothing like the transitions of the past.

The technology model: From application silos to a system of intelligence

The technology shift unfolding now is far more complex than the move to cloud. The cloud era changed the operational model for running the same application silos – breaking monoliths into microservices but leaving the underlying fragmentation intact. Data remained siloed, and even the application logic itself stayed isolated within domain-specific systems.

What is happening now is much different. For decades, enterprises converted data into a corporate asset through the rise of relational databases. That was a significant milestone, but it didn’t unify how businesses reason. In the agentic era, humans and agents need a shared understanding of the rules, processes and semantics that govern the enterprise. That requires constructing a true system of intelligence or SoI – a shared asset that expresses how the business runs.

This is something the industry has never done before, and it upends 60 years of accumulated investment in application-centric architectures. Developing a migration path for this transformation is extraordinarily challenging, because every existing enterprise today is built on top of layers of deterministic logic that reflect the constraints of siloed automation.

The “Tower of Babel” metaphor on the slide above captures the legacy landscape. Each application has its own language, its own worldview, its own schema. They don’t talk to each other. Even when organizations attempt to consolidate through a lakehouse, the silos reappear inside the lakehouse itself – sales, service, logistics and every other domain carries its own schema, definitions and constraints.

Asking cross-functional questions – for example, what happened, why it happened, what should happen next – requires stitching these worlds together with extensive data engineering. This is brittle work, and it reinforces the fragmentation that enterprises are now trying to escape.

The move from application-centric silos to a unified, data-centric platform is not simply a technology upgrade. It is a rearchitecture of how intelligence is represented inside the enterprise. And it is this shift that will determine whether organizations can deploy agents that truly understand and drive end-to-end business outcomes.

Kicking a thousand dead whales down the beach

The slide above depicts a dead whale being kicked down the beach – an intentionally stark metaphor for the scale of the challenge ahead. The reference traces back to Microsoft Corp. co-founder Bill Gates, who once mocked attempts by Lotus and WordPerfect to bolt graphical interfaces onto DOS-era software. He likened that effort to “kicking dead whales down the beach” – an impossible, grinding task weighed down by accumulated legacy code and technical debt.

The situation today is exponentially harder. Instead of a single dead whale, the industry faces a thousand. Sixty years of investment in application-centric silos must now be harmonized into a coherent systems of intelligence. Every layer of legacy logic, schema, workflow and domain-specific constraint has to be reconciled. And at this moment, no one vendor has a complete solution for how to do it.

The metaphor captures the reality in that preserving compatibility with decades of siloed systems while attempting to build unified, agent-ready architectures is not only difficult – it borders on impossible without rethinking the foundational architecture of the business. The agentic era demands a level of semantic, procedural and data harmonization that legacy architectures were never designed to support.

In this next section, we’ll turn to what the broader transformation means for AWS. A series of announcements at re:Invent – general availability milestones, continued investment in Kiro, enhancements across the software development lifecycle, and significant expansions to Nova and Nova Forge – underscore how AWS is positioning itself for the service-as-software era.

But before we do that, let’s revisit how we see the emerging technology stack evolving.

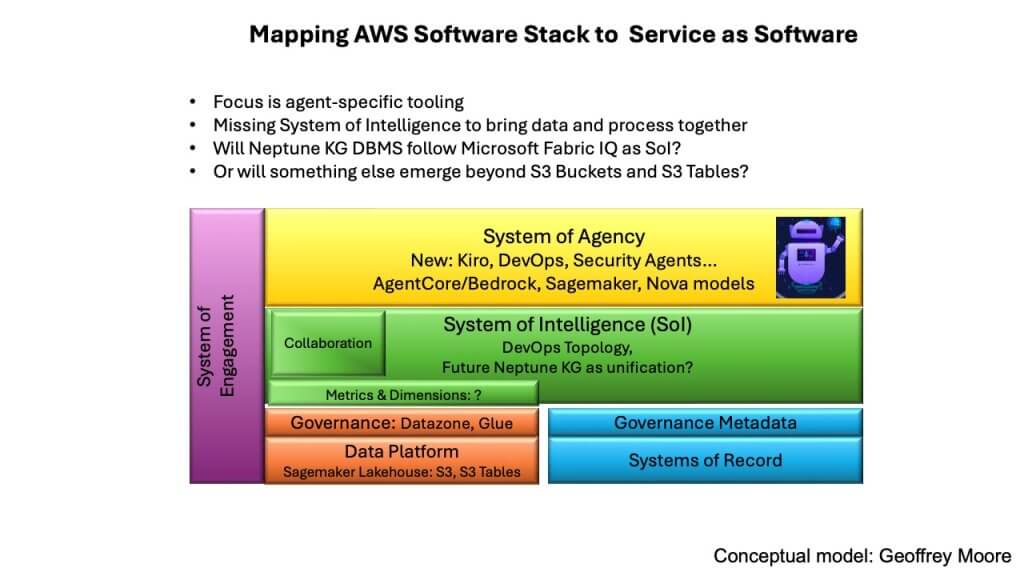

The emerging software stack: Data platforms, systems of intelligence, and systems of agency

The slide above depicts the transition from application-centric silos to a data-centric platform. At the base sits the data platform – the logical data estate aggregating information from operational systems, websites and external sources. Vendors such as Snowflake Inc., Databricks, and AWS with its Redshift have done remarkable work consolidating these assets.

But consolidation is not the same as harmonization. The data platform remains neither machine-readable nor agent-readable. Even humans often require a business intelligence layer to interpret it. Functionally, these systems provide high-fidelity snapshots of what happened – two-dimensional views constrained by the schemas of each domain. At best, with feature engineering and narrow machine learning, they can forecast what’s likely to happen within a limited scope.

What enterprises need next is a true system of intelligence, represented in green on the slide. We’ve discussed previously the need for a four-dimensional, end-to-end map of the business. This is the layer that gives both humans and agents a shared understanding of processes, rules and dependencies. Some organizations attempt to build this today with platforms such as Palantir, but doing so often requires forward-deployed engineers or FDEs crafting bespoke solutions at great expense (~$1 million annually for each FDE). Each customer effectively rebuilds the system from scratch.

Above that sits the system of agency, shown in yellow. This is the agent control framework – important for orchestration, policy and workflow activation, but not itself the source of intelligence. It draws meaning from the system of intelligence beneath it. For agents to make decisions with the same contextual awareness humans use today – understanding, for example, how delaying an order for lack of a part could jeopardize a major contract – they must be anchored in a harmonized representation of the enterprise.

Without that harmonization, neither humans nor agents can reliably see across domains or reason about second- and third-order effects. Humans can run isolated what-if analyses, but scaling those insights across the full enterprise is impractical when the underlying maps must be stitched together manually.

The key point is that the emerging software stack requires customers to transform their technology model. The data platform alone is not enough. Systems of intelligence and systems of agency must work in tandem to provide the end-to-end visibility, shared meaning and decision-making context that define the agentic era.

The next question we want to address is how AWS maps onto this architecture – and where its recent announcements signal its intent to lead.

Mapping AWS onto the emerging software stack

With the benefit of four days of re:Invent behind us, a clearer picture emerged of where AWS is investing and how it aligns to the evolving software stack shown above. When mapped against the model of data platforms, systems of intelligence, and systems of agency, the green layer – the system of intelligence – is still largely incomplete. It doesn’t come out of the box. Enterprises such as JPMorgan Chase, Dell Technologies Inc. and Amazon.com Inc. itself have had to build it themselves, whereas most mainstream enterprises don’t have the capability to do so.

Where AWS is strong today is in the layers surrounding that gap. Bedrock has matured considerably. A year ago, reliability issues – struggles even with two and three nines – triggered urgent internal focus. That work appears to have paid off. Bedrock now serves as the abstraction layer above LLMs that AWS has long needed. AgentCore, introduced as a control framework for building multi-agent systems, shows real promise as well.

Even more compelling are AWS’ first-party agents. The Kiro autonomous coding agents, along with new DevOps and security agents, formed some of the most interesting narratives of the week. They still have to earn customer trust, but the conceptual story around them is strong.

These agentic capabilities, however, highlight the critical dependency on the missing middle layer. Agents are only as effective as the context they draw from. AI is programmed by data, and without a well-structured system of intelligence to feed them, their potential is limited.

At the bottom of the stack, the data platform continues to evolve. SageMaker’s lakehouse features – especially S3’s expansion into table formats such as Iceberg – signal S3’s shift from a simple get/put object store into something more structurally aware. Neptune, AWS’ graph database, receives far less public attention, including its knowledge graph capabilities, yet it represents an important ingredient for shaping contextual data. in our view.

This is where the divergence between AWS and Microsoft is instructive. Microsoft prefers to articulate where customers should be three to five years out and seed early product iterations – Fabric IQ being a recent example, potentially even designed to counter Palantir Technologies Inc.’s momentum. AWS, by contrast, tends to stay one step ahead of customers’ stated needs, solving problems incrementally rather than prescribing long-horizon architectures.

Even so, Neptune already plays a role in bottom-up AI workload development, helping customers structure data for agentic applications. And one can imagine a future where Neptune joins S3 buckets and S3 tables as a more central mechanism for harmonizing data, though that would represent a strategic evolution for AWS.

The broader takeaway is that AWS is prioritizing agent-specific tooling. As Swami Sivasubramanian, Amazon’s vice president of agentic AI, put it in his keynote, the company wants to be “the best place to build agents.” On that dimension, progress is evident and deserving of high marks. But the system of intelligence – the contextual substrate agents depend on – is still an open frontier across the industry. Vendors such as Palantir and Celonis SE operate directly to address this space, but no one vendor has yet solved the problem at scale.

AWS may lean on Neptune, expand the capabilities of S3, or take a different path altogether. What’s certain in our view is that the green layer – the harmonized representation of data and process knowledge – is the piece that will ultimately determine how far agentic architectures can go.

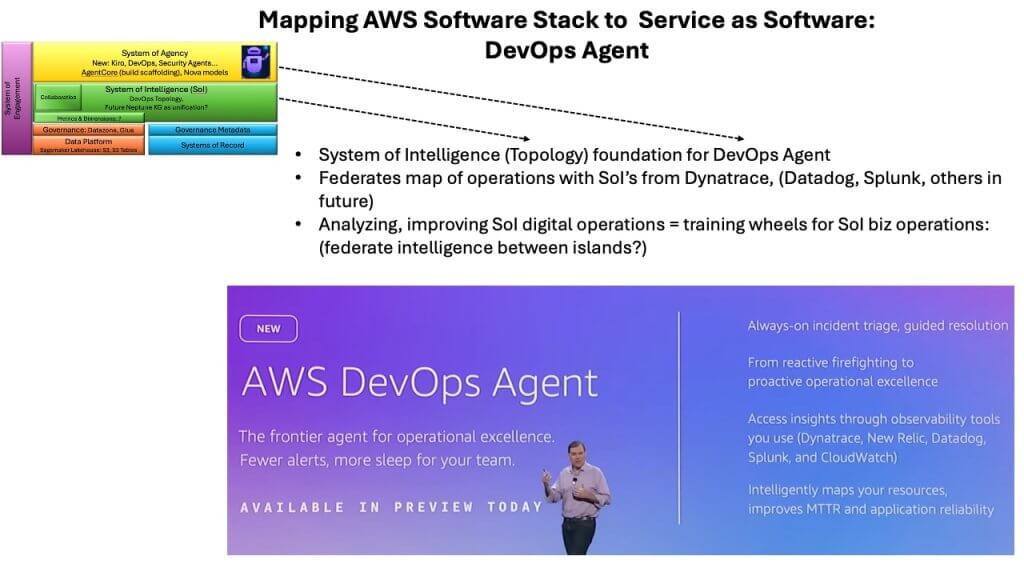

DevOps agents as the training wheels for a system of intelligence

The DevOps agent emerged last week as one of the most consequential pieces of AWS’ agentic strategy. When mapped onto the emerging software stack – systems of intelligence in green and systems of agency in yellow – the DevOps agent sits in the layer that orchestrates digital operations. Understanding why this matters requires looking at the complexity of modern enterprise estates.

A DevOps agent must reason across sprawling, heterogeneous environments composed of infrastructure, middleware, application components and thousands of microservices. Unlike a monolithic system such as SAP, where a single vendor created an end-to-end framework with well-understood internals, AWS environments are far more open-ended. The DevOps agent is designed to look across all of digital operations, identify when something breaks, determine the root cause and, when confidence is high enough, execute a remediation plan – potentially without human intervention.

This introduces an important concept in that DevOps agents function as training wheels for the broader system of intelligence. They represent a prototype of what an enterprise-wide reasoning layer could become. Digital operations are only one slice of the problem. The full system of intelligence must encompass all business operations, and that requires a 4D map of the enterprise that shows how systems connect, their dependencies and how actions in one domain influence outcomes in another.

AWS described this mapping capability as topology – an attempt to learn a representation of how Amazon services and infrastructure components interrelate. Conversations with vendors such as Datadog Inc., Dynatrace Inc., Splunk Inc. and Elasticsearch B.V. revealed that each has deep visibility into its own domain and partial insight into adjacent ones. Dynatrace, for example, places a probe on every host, enabling it to construct a causal graph – a kind of twin of digital operations.

The DevOps agent uses these external views when needed. When it identifies a problem but lacks sufficient visibility to diagnose it, it can call out to partners such as Dynatrace and say, in effect: Run the deeper query for me. This bottom-up collaboration hints at how a general system of intelligence may ultimately emerge – not as a single monolithic product but as an aggregation of increasingly broad platforms across an ecosystem.

This raises a broader architectural question related to top-down versus bottom-up approaches. A pure bottom-up approach risks “boiling the ocean” – digging two tunnels from multiple directions without a guarantee that the tunnels meet in the middle. A purely top-down approach lacks grounding in operational reality. The workable model appears to be a hybrid where the the outcome is defined top-down, then stitched together with the necessary data bottom-up to support that outcome.

In practice, this might look like deploying the DevOps agent for a specific service area and augmenting it with Dynatrace data to achieve end-to-end visibility. Once that outcome works, extend it incrementally to additional services. This creates the scaffolding for a system of intelligence one outcome at a time – a middle-out expansion if you will, anchored by practical workflows.

The DevOps agent therefore serves two purposes: 1) It solves a tangible operational problem today; and 2) It lights the path toward an enterprise-wide intelligence layer that will ultimately govern agentic systems.

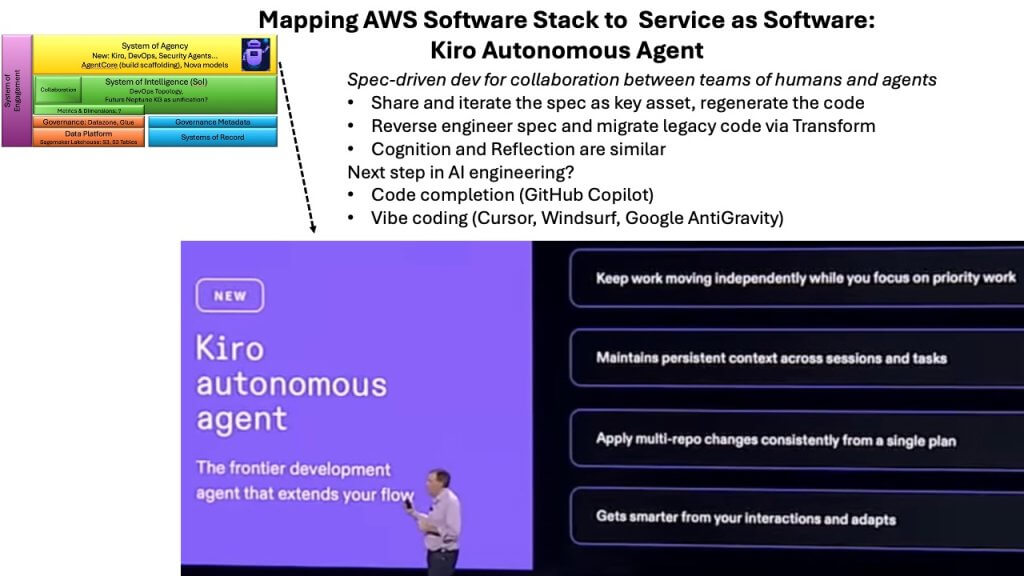

Kiro: More than vibe coding

Kiro, first announced at the AWS Summit in New York, took on new significance last week. Anyone who still believes AWS is behind in AI need only look at the cadence and depth of innovations emerging around Kiro and its autonomous coding capabilities. Despite that, the keynote significantly understated its importance, in our view. Developers we spoke with emphasized that Kiro is quickly becoming central to their workflows. And the reason is that Kiro goes beyond the vibe-coding paradigm that has dominated the last year. Developers, by the way, still love Cursor, which continues to sets the standard.

For months, the conversation in AI-assisted development has centered on scaffolding – the supporting structures that transform rapidly evolving models into agentic applications. Tools such as GitHub Copilot pioneered “code complete” – hit tab, finish your line. Cursor advanced the state of the art by customizing the integrated development environment so developers could chat with the agent, enabling longer-horizon tasks. Google’s Antigravity, which came from the Windsurf acquisition, followed the same path.

These tools are powerful, but they remain forms of vibe coding. The artifact is still the code. You live in the code. You fix the code. The scaffolding evolves as models advance.

Kiro breaks from this model and enters new ground.

Instead of writing code and letting the agent assist, Kiro starts upstream – with the requirements document. The agent works at the ideation level, partnering with the developer to flesh out specifications, tighten ambiguities, highlight missing details and introduce best practices. The requirements document then feeds into a design document, creating a clear specification. Only then does Kiro generate code.

And crucially, the code is disposable. When the software needs to evolve, you don’t traverse through the codebase trying to predict what will break. You update the requirements, adjust the design and regenerate the code from the spec.

This reverses decades of software engineering logic. The artifact is no longer the code – it is the specification. Though Cursor can function similarly, it is still code-first out of the box.

Even more striking is the potential impact on legacy systems. AWS’ Transform product can reverse-engineer a design document from an existing codebase. AWS believes it can go further and generate the requirements specification itself. That opens the door to something the vibe-coding world has not addressed – brownfield modernization. Instead of writing elaborate migration plans or manually dissecting aging monoliths, enterprises may be able to produce specifications from legacy code and move forward iteratively, regenerating components as needed.

This is why Kiro is so significant, in our opinion. It elevates the abstraction from writing code to defining intent. This aligns with the broader shift toward agents, systems of intelligence, and outcome-oriented architectures. When AWS first introduced Kiro, it gave a nod to vibe coding because it was the trend of the moment. But even then, they hinted that Kiro represented something more. The story last week at re:Invent emphasized this is not another flavor of assisted coding. It is a new model for how software gets built, maintained and evolves.

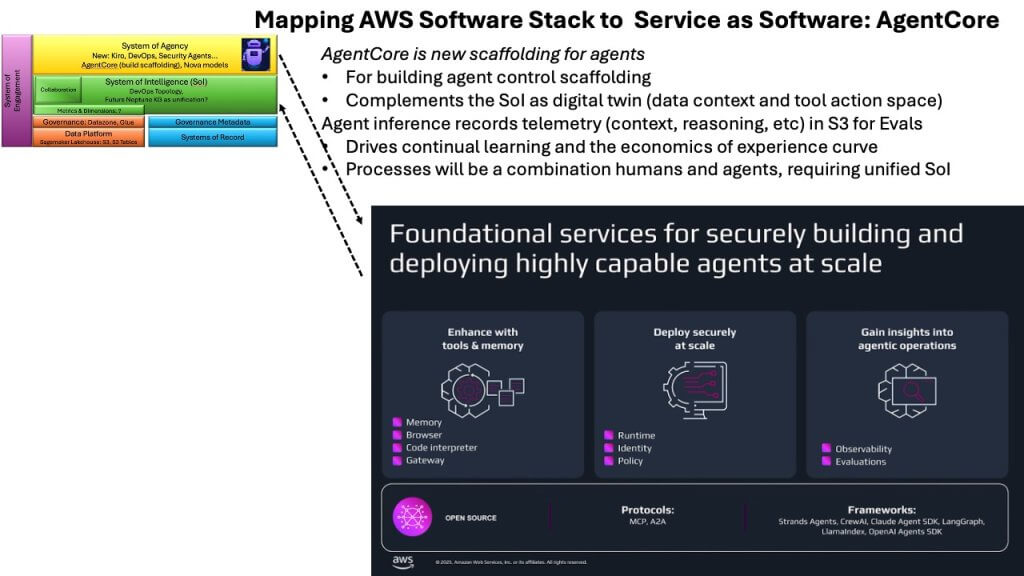

AgentCore: The control plane for teams of agents

AgentCore emerged as one of the most pivotal announcements of the week because it represents the scaffolding required to make agents production-grade. Bedrock has steadily matured into the foundational abstraction layer for model access, but AgentCore sits alongside it as the operational backbone for multi-agent systems. It is the control infrastructure that governs how agents behave, how they coordinate and how they remain within defined boundaries.

AgentCore provides the essentials of memory, runtime services, utilities like code interpreter and – critically – observability and policy enforcement. These capabilities matter because agents are not like traditional software components. Governing a data platform is relatively straightforward. Policies answer simple questions like who can access which data, under what conditions? Even column-based or tag-based controls remain manageable within deterministic systems.

Agents are different. They take actions. They chain actions. They invoke tools. They do so with varying parameters, in varied contexts, and with probabilistic reasoning. The policy framework must therefore answer far more complex questions such as: Should this agent be allowed to take this action, with these parameters, in this context, in pursuit of this goal? That level of governance is exponentially more sophisticated than anything required in legacy data or application systems.

This is why AgentCore is significant. Putting agents into production requires deterministic enterprise scaffolding – strong guardrails, clear boundaries, actionable observability and the ability to enforce policy across dynamic behaviors. This is heavy enterprise software, not something LLM vendors are likely to deliver. Frontier labs focus on models, not operational governance. Enterprises need a control plane that can manage armies of agents reliably, safely and consistently. Again, this is a debate inside theCUBE Research, which we’ll continue to explore.

AgentCore begins to fill this gap. It establishes the governance fabric that agents must operate within and provides the layer into which downstream capabilities – systems of intelligence and systems of agency – will ultimately connect. It is the early architecture of agent-native operations, and AWS appears intent on owning this part of the stack.

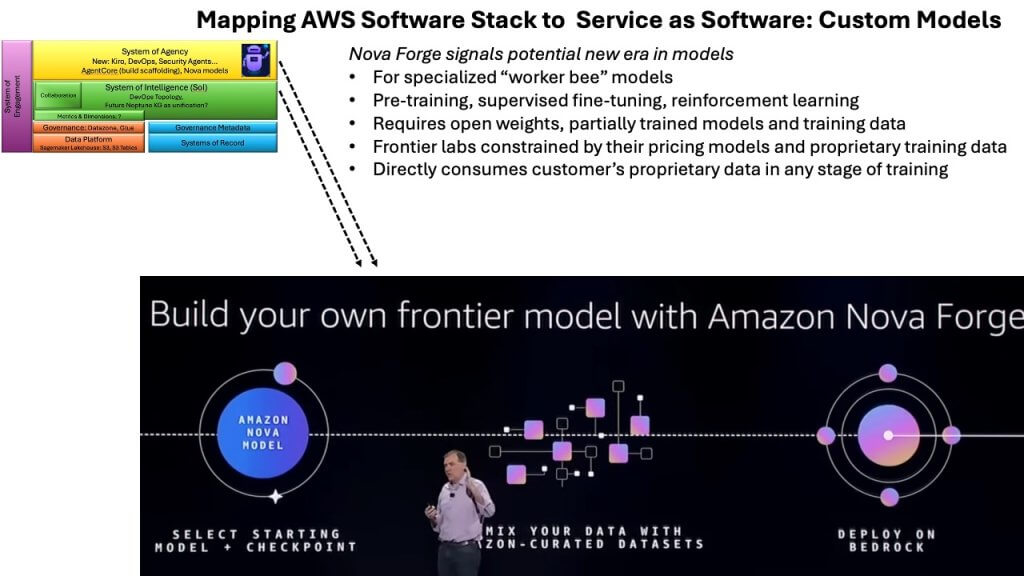

Nova Forge: Perhaps the most important announcement of the week

Among all the news coming out of re:Invent, Nova Forge stands out as the most strategically significant. The framework aligns directly with our thesis that enterprises will differentiate by owning their data, customizing their models, and building systems of intelligence that reflect their proprietary workflows. Nova Forge serves as the mechanism that makes this possible. It is the first offering from a major U.S. vendor that delivers open weights and training data, giving customers the ability to adapt the model to their own environments.

The availability of training data is a critical distinction. While startups continue to build on lower-cost open-weight models such as DeepSeek, those offerings generally include weights only – not the underlying data. Nova Forge allows enterprises to substitute, augment or extend the training corpus with their own information, creating a model tuned to their specific context and competitive advantage.

This introduces several strategic dynamics. Customizing a model through pretraining or reinforcement learning effectively welds an enterprise to that version of the model. When the next, more capable model arrives months later, the tuning process must be repeated. The complexity is not just operational – it can introduce behavioral instability as models shift.

This is why some frontier-model providers, particularly those whose businesses depend on API consumption, actively discourage customers from performing deep reinforcement learning. Their pitch is if you avoid the heavy customization, you sacrifice some tight integration but stay aligned with the rapid improvement cycle of frontier models.

This perspective underscores a broader debate about how the enterprise AI stack will evolve. One argument holds that frontier-model companies will become the next great software vendors, providing layers of tooling atop their LLMs to simplify enterprise integration. The counterargument is that mainstream enterprises – and the ISVs serving them – will need far more specialization than a handful of frontier models can deliver. Agents are not just RPA 2.0; they represent much more. As these agents proliferate, organizations will require a diverse portfolio of models, many of them small and highly specialized.

In that world, frontier models play a role – but as orchestrators, handling complex planning and reasoning. The bulk of enterprise differentiation will come from customized, specialized models trained on proprietary data. Nova Forge is the first major signal that AWS intends to support this path by delivering open weights, open data and the ability for customers to shape the intelligence layer of their enterprise directly.

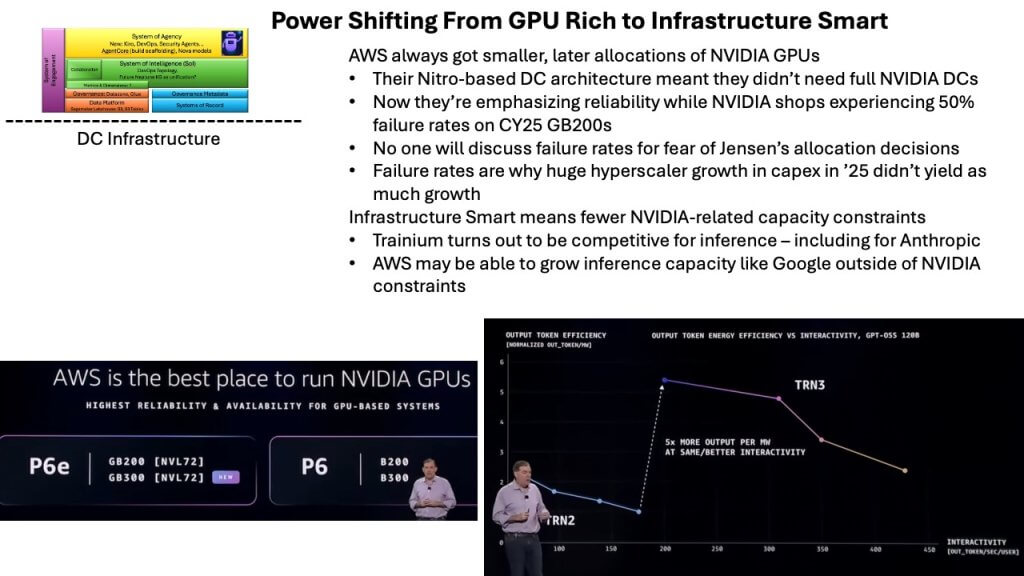

Nvidia, AWS and the GPU power dynamics behind the AI infrastructure race

A major subplot at re:Invent was AWS’ forceful claim that it is the best place to run Nvidia Corp. GPUs. That declaration hits with irony, given the persistent narrative that AWS lacks allocation, faces political challenges with Nvidia, and is focused on its own silicon efforts – Trainium in particular. Meanwhile, public commentary from outlets such as CNBC continues to over-index on competition to Nvidia, framing tensor processing units, Trainium and other accelerators as existential threats.

The reality is more nuanced. GPUs are expensive, and performance per watt is the defining metric. Volume determines learning curves. And on that dimension, Nvidia remains in the driver’s seat. High volume gives Nvidia cost advantage, supply advantage and architectural advantage. Unless the company stumbles, the position is theirs to lose.

Nvidia also locked up the leading process nodes at Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. securing massive capacity. It is reminiscent of Apple Inc. 15 years ago: No competitor could match its handset performance because Apple had tied up the most advanced silicon for entire product cycles. No alternative supplier could close the gap.

AWS’ historical challenge in securing Nvidia volume traces back to its own infrastructure strategy. The company spent years building Nitro, designing composable data centers, expanding instance types, optimizing storage and networking, and refining hypervisors. That approach made AWS infrastructure-smart – but not the earliest or largest buyer of full-stack Nvidia systems.

When the ChatGPT moment hit, Nvidia wanted to sell integrated data center kits, not just racks. Providers that lacked infrastructure sophistication were forced to buy everything, and in return they received the larger allocations. That included Microsoft and the neoclouds, and Oracle as well – though in Oracle’s case, the scale-up design served the needs of its database architecture.

Then came a second, largely unspoken issue: failure rates. For the last 12 months, the volume GPU has been the GB200. Multiple sources reported that failure rates were as high as 50%. No one talked about it publicly. The industry was reluctant to make Nvidia look bad and risk a reduction in allocation.

But the implications were that supply would continue to be constrained. This was the year hyperscaler capital spending surged, and Wall Street was left wondering where the returns were. Utilization was low for reasons almost nobody understood externally.

The shift began in October, when the GB300 surpassed the GB200 in volume. The GB300 installs more smoothly, runs more reliably and appears to deliver meaningfully higher quality. Neocloud providers such as Lambda reported excellent performance from GB300 systems. As GPU specialists willing to buy full stacks, they secured allocations consistent with that model.

This dynamic contributed to the broader narrative of the “GPU-rich” and the “GPU-poor.” The GPU-rich could advance model training, inference and agentic workloads aggressively, while the GPU-poor were stuck rationing capacity. But now the dynamics may change as infrastructure-smart providers – those that invested in custom silicon and composable data centers – begin to leverage their own accelerators for meaningful workloads.

There is enough Trainium deployed inside AWS to run frontier models such as Anthropic for inference at scale. Training remains a different story, despite public commitments on both sides. Anthropic’s leadership has acknowledged that training on Nvidia would require far fewer chips, which explains why it negotiated a larger deal with Google to run on TPUs – even as AWS invested billions in the company.

Still, TPU volume will remain limited. Google will not match Nvidia’s scale unless Nvidia falters. Nvidia sells to Google’s competitors. Neoclouds depend on Nvidia allocation and are unlikely to compromise it. Neither Amazon nor Microsoft is going to shift to TPUs. Volume determines trajectory, and Nvidia’s volume remains unmatched.

Could TPUs create pricing pressure? Possibly. A credible competitor gives buyers negotiating leverage. Nvidia’s 70% margins may face some compression. But the software ecosystem, tooling, libraries, and developer familiarity remain heavily skewed toward Nvidia.

The lesson from this week is that AWS is becoming more assertive about the GPU story because it believes its infrastructure – combined with Nitro, Trainium and rapidly improving Nvidia integration – positions it strongly for the next phase of AI infrastructure. But the industry-wide GPU story is more complicated than energy constraints and data center buildouts. It includes an unspoken constraint in that high GPU failure rates, massive CapEx tied up in underutilized infrastructure, and a rapidly maturing next-generation GPU cycle is reshuffling the hierarchy of who is GPU-rich and who is GPU-poor.

Chasing messiah AGI vs. enterprise AI

The slide above tells the story of two worlds. On the left sits the pursuit of messiah-level AGI – the frontier labs chasing grand breakthroughs. On the right is the hard, unglamorous scaffolding required to make AI useful in enterprises. The contrast underscores a fundamental divide.

The frontier narrative often centers around singular breakthroughs and personalities, while the enterprise ecosystem is focused on building practical systems. The hyperscalers, ISVs and large incumbents are constructing the heavy scaffolding at both the agent layer and the data layer. AgentCore represents the control and governance framework. But the other half of the equation is even more foundational – bringing together data and action in a consistent, governed system.

Actions – meaning tools and callable workflows – must pair with data, which provides the context that guides what an agent should do. When those come together coherently, the result is a knowledge graph, and that “4D Map” becomes the system of intelligence. This is hard enterprise software work, and frontier LLM vendors are not database vendors or workflow vendors. They are a long way from building this substrate.

Enterprises that operate at scale – Amazon.com, large banks such as JPMorgan, and major technology firms that include Dell – confirm that they must build this system of intelligence themselves. It does not exist out of the box.

Our early work, such as the “Uber for All” model explored years ago, hinted at the idea of people, places, things, activities – drivers, riders, prices, locations – brought together into a unified digital representation of an enterprise. That remains the ambition today: a real-time, four-dimensional map of the business.

It’s why the agentic era will take most of a decade to unfold, in our view. Analytics-oriented vendors can provide slices of this capability today, but only within confined analytic domains. Building the full operational twin of the enterprise – harmonized, contextualized and ready for agents – is a far larger undertaking.

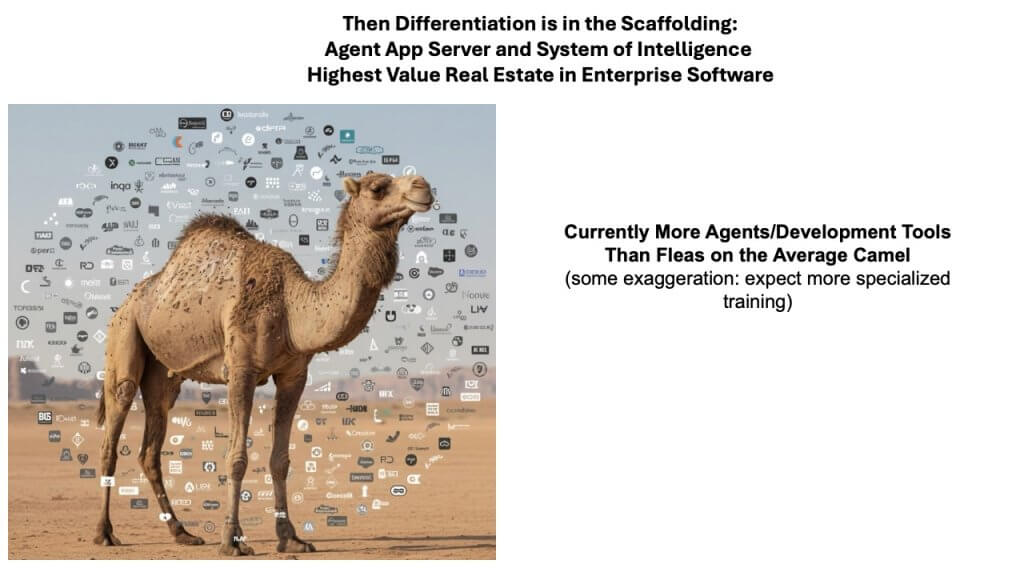

A camel covered in agent startups

The slide above shows a camel covered in logos – more logos than a camel has fleas. The image captures the current frenzy. The market’s reaction to the word “agent” has resembled a Pixar moment when someone yells “squirrel,” and the dogs instantly lose focus. In this cycle, someone yells “agent,” and venture capital runs at full speed.

The problem is that most of these agent startups are built on only the thinnest layer of scaffolding. Some domain agents – such as those in legal tech – carry embedded knowledge of workflows. But the vast majority lack the heavy lifting required for real enterprise value. They do not solve the integration challenge between data, action space, and governance. They do not provide the agent control apparatus. They do not offer the system of intelligence.

The companies doing that work are the hyperscalers and the major software vendors. The differentiation will not come from shiny agent UIs or narrow features. It will come from the depth of integration with data systems, workflow systems and the governance and control planes that bind agents to enterprise policy and process.

That’s why this era will be defined not by the number of agents a vendor can showcase, but by the scaffolding that underpins them. And that scaffolding is where the real enterprise value will accrue in our view.

The future stack and the high-value real estate: Systems of intelligence at the center

The final slide above ties the entire discussion together, showing how the emerging software stack will take shape and where different players fit. The center of gravity – the high-value real estate – is the system of intelligence layer. Companies such as Celonis and Palantir are furthest along, in our view, though they take different approaches. Palantir remains services-heavy but has made significant software advances. Other graph-centric and process-centric vendors such as ServiceNow Inc., SAP SE, Salesforce In. and essentially every SaaS company with embedded process logic, are now targeting this same layer.

To participate meaningfully, these players must build out their data platforms and confront a major business-model transition. As they merge process logic with data and enable agents to take increasingly autonomous action, they weaken their traditional seat-based subscription models. This is an innovator’s dilemma in real time. For example a $50 billion dashboard-centric industry (BI) faces disruption. Efforts to introduce “talk to your data” interfaces are part of that response, but they do not change the underlying economics.

Below the system-of-intelligence layer sit the data platforms: Snowflake, Databricks and the lakehouse constructs of SageMaker and S3. Above it sits the system of agency – Bedrock and the agent-control frameworks. And throughout the stack, governance is ubiquitous; every major player is adding governance layers to address the risks of agentic systems. Meanwhile, the software development lifecycle is shifting from a linear pre-gen AI workflow to one that is nonlinear, interactive and deeply agent-driven. As the hardware stack is redefined – compute, storage and networking – the entire software stack is being redefined with it.

Closing thoughts: Messiah AGI, worker-bee AGI and what comes next

Zooming out from re:Invent 2025 and the broader move toward service-as-software, the momentum feels like early baby steps toward a decade-long transformation.

Two major trends are emerging:

- Consumer AI entrenches toward incumbent players

The consumer agent story, once dominated by frontier labs, shows signs of settling into existing ecosystems. Android provides a natural surface for Google’s now industry-leading model. Apple’s initial missteps have given way to tighter integration with Google, allowing Apple to upgrade Siri without heavy CapEx. That leaves OpenAI trying to establish itself as a desktop or mobile third-party app – but without a native platform, its consumer position becomes harder. - Enterprise AI accelerates in two directions

The enterprise landscape will focus on two categories:- Worker-bee AGI (the enterprise automation and RPA-plus domain discussed throughout this analysis)

- Agent-enabled software tools, meaning every development, security, operational and business application becomes agent-augmented – Kiro, DevOps agents, security agents and eventually every service provided by every vendor.

The bubble is not bursting, but it is growing. There may be some deflation on the consumer side, particularly around OpenAI’s positioning, but enterprise activity is only beginning. Building worker-bee AGI beyond basic RPA 2.0 and microservices 2.0 is a long, challenging road. But the productivity gains across software development and operations tools will be large and immediate.

Over time, those agentic capabilities will migrate into every enterprise process, creating the marginal-economics advantage that defines the service-as-software model. The broader market dynamics may feel bubblicious – echoing Ray Dalio’s comment that we’re “80% of the way into the bubble.” Whether that was macro commentary or a push for his preferred trades, the point stands in that bubbles don’t burst until something pricks them.

We’re not there yet. History shows pullbacks of 10% or more can happen repeatedly during an expansion, as they did in the dot-com era. Recent market disruptions look more like early tremors than the hard correction that would unwind current valuations.

The agentic era is coming. Its shape is becoming somewhat more clear. But the real transformation – the unified data foundation, the system of intelligence, the governed agent layer – will take the better part of a decade to mature.

Disclaimer: All statements made regarding companies or securities are strictly beliefs, points of view and opinions held by News Media, Enterprise Technology Research, other guests on theCUBE and guest writers. Such statements are not recommendations by these individuals to buy, sell or hold any security. The content presented does not constitute investment advice and should not be used as the basis for any investment decision. You and only you are responsible for your investment decisions.

Disclosure: Many of the companies cited in Breaking Analysis are sponsors of theCUBE and/or clients of Wikibon. None of these firms or other companies have any editorial control over or advanced viewing of what’s published in Breaking Analysis.

Image: theCUBE Research

Support our mission to keep content open and free by engaging with theCUBE community. Join theCUBE’s Alumni Trust Network, where technology leaders connect, share intelligence and create opportunities.

- 15M+ viewers of theCUBE videos, powering conversations across AI, cloud, cybersecurity and more

- 11.4k+ theCUBE alumni — Connect with more than 11,400 tech and business leaders shaping the future through a unique trusted-based network.

About News Media

Founded by tech visionaries John Furrier and Dave Vellante, News Media has built a dynamic ecosystem of industry-leading digital media brands that reach 15+ million elite tech professionals. Our new proprietary theCUBE AI Video Cloud is breaking ground in audience interaction, leveraging theCUBEai.com neural network to help technology companies make data-driven decisions and stay at the forefront of industry conversations.