If you ever need a fertility clinic, you wouldn’t need to do much research. IVF centres advertise on billboards. Surrogacy labs occupy premium real estate in medical districts. These are visible, accessible, and increasingly normalised parts of the healthcare landscape.

Now, try to find a specialist in chronic pelvic pain. Try locating a clinic that treats vaginismus or dyspareunia, conditions that make sex painful or impossible for millions of women.

The disparity isn’t accidental. It’s economic. And economics, at its core, is about values: what a society has decided matters enough to fund, build, and sustain.

Fertility is funded not because it’s objectively more important than pain management, but because we’ve decided, socially and culturally, that a woman’s ability to reproduce is more valuable than her ability to live without suffering. Long before investors enter the picture, society has already ranked what matters. That calculus is now embedded in the global femtech market.

The numbers tell a story if you’re willing to read it

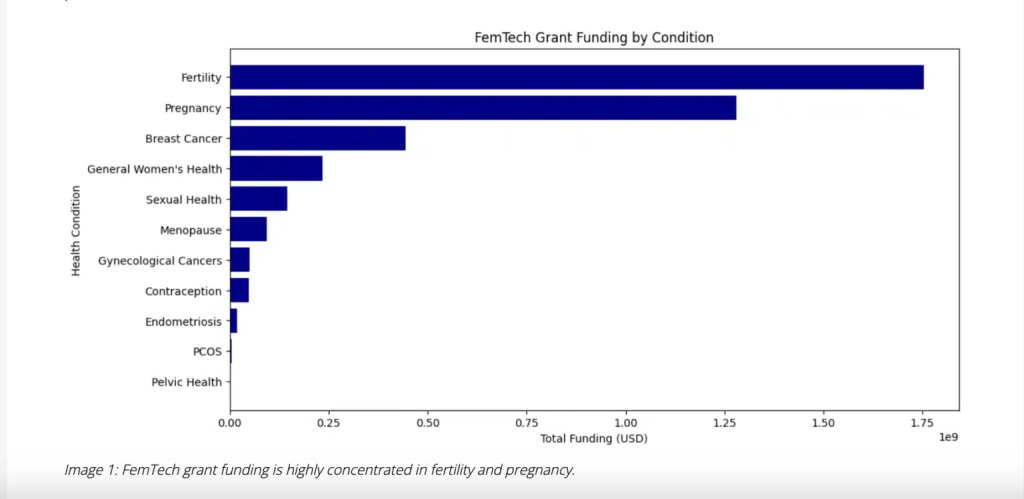

Global femtech funding has grown from $107 million in 2012 to $2.6 billion in 2024, according to Statista. Preliminary estimates place 2025 as high as $8.5 billion. Even though femtech still accounts for just 8.5% of total global digital health funding, the growth suggests progress. Until you zoom into the distribution.

Data from Dimensions AI, a global database of research insight, shows that fertility and pregnancy capture over 74.24% of femtech funding, while menopause and breast cancer have gotten only 10.9% and 0.55%, respectively. Pelvic health, endometriosis and PCOS remain almost invisible. These neglected areas exist in what Amboy Street Ventures calls “ghost markets”: vast pools of unmet clinical and commercial needs that are functionally invisible to investors.

Endometriosis affects an estimated 190 million women globally, yet funding for research and innovation lags decades behind less common conditions. Chronic pelvic pain is so undertreated that many women spend years cycling through doctors, misdiagnosed, or told their pain is psychosomatic. The funding disparity isn’t about need. It’s about what venture capital finds legible, scalable, and investable. It is more comfortable funding women’s capacity to reproduce than their right to live without pain.

In Africa, the pattern repeats

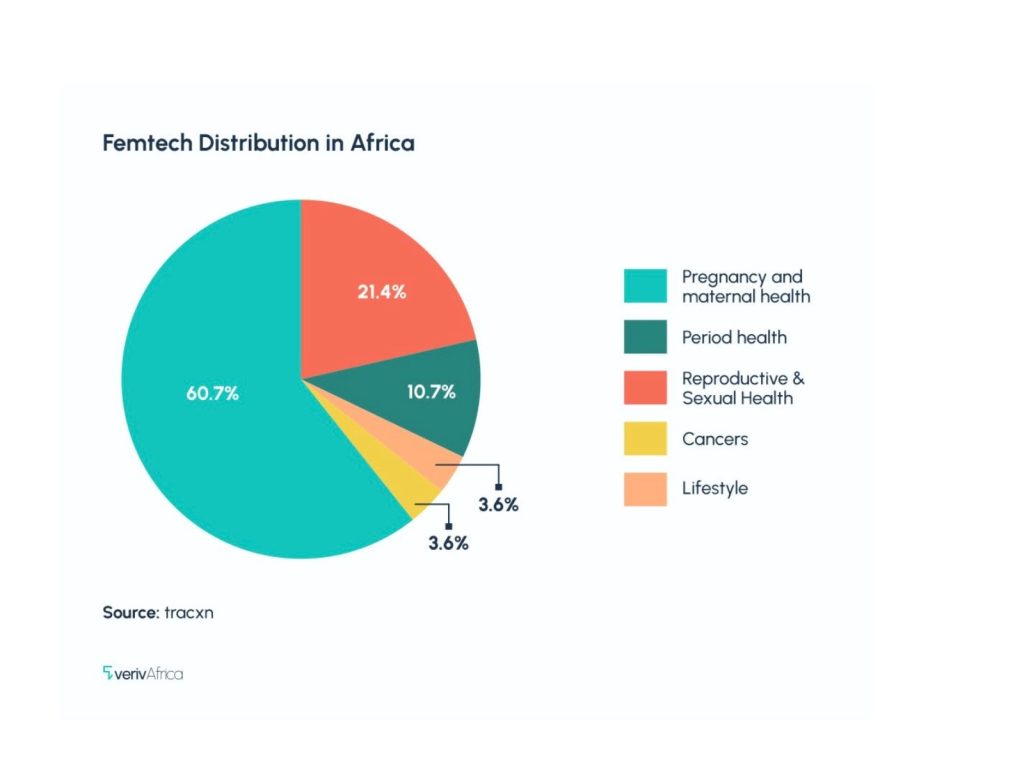

In Africa, the same hierarchy appears. First in infrastructure, and then it trickles into funding.

Halima Mason, the founder of Sexual Wellness Holistically, has noted that women often engage the medical system only in the context of reproduction, while concerns about desire, pleasure, or pain are managed privately. Support exists in small pockets: a few therapists and counsellors, some progressive gynaecologists, and a limited number of pelvic physiotherapists, mostly in major cities.

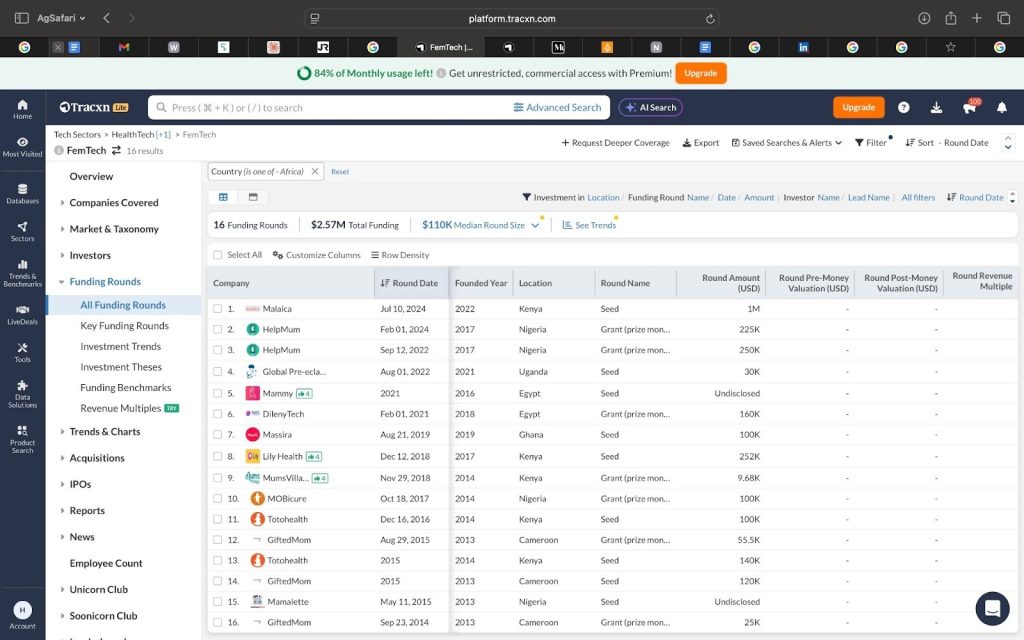

This infrastructure gap mirrors the funding gap. About 100 femtech startups operate across Africa, yet about 81% of those that have raised funding focus on pregnancy and fertility.

Startups like Grace Health and Susu Health have raised millions for fertility and maternal health services. BabyMigo has attracted grants to support pregnancy care.

In the past three years, there has been an increasing number of femtechs launching across Africa. Most of it is due to stakeholders, both founders and investors, recognising the commercial potential after the sector’s success in other regions. Yet, most of the investors fund the parts they understand: fertility and pregnancy. Pain, pleasure, and wellness remain unfundable because they don’t fit established narratives about women’s value.

This reflects what feminist economist Marilyn Waring observed decades ago: economic systems consistently undervalue women’s wellbeing concerns, because they were designed to reward productivity. Medical historians have documented how women’s bodies were excluded from medical research because they were seen as too complex, too variable, and too costly to study. Unfortunately, current femtech funding reproduces this. Areas of women’s health that are non-normative or difficult to standardise remain underfunded, while fertility, which fits existing biomedical and economic narratives, attracts capital.

What this means

This isn’t about whether fertility care matters. It does. But it is deeply revealing that women’s ability to reproduce attracts far more attention, infrastructure, and capital than women’s ability to live without pain.

The challenge for 2026 isn’t just femtech’s growth, as growth alone doesn’t equal justice. It’s whether femtech will challenge the ideologies that created these disparities, or simply replicate them at scale. It’s which women, which bodies, and which forms of suffering we are willing to fund.

For founders, this means recognising that “ghost markets” are not marginal problems, but evidence of unmet demand created by historical neglect. For investors, it requires interrogating their own biases about the kind of solutions they’re more eager to fund, and why their investment priorities stop at reproduction.

_____

Hannatu-Favour Asheolge Moses is a journalist and the founder of TheSARAH Project, a women’s health research and storytelling community.