Modern backend systems are increasingly asked to do more than serve requests. They ingest continuous streams of events, process historical data at scale, recompute results when business logic changes, and remain correct in the presence of partial failures. For engineers coming from a REST API background, this shift often feels unintuitive: the tools, abstractions, and even the definition of “done” are fundamentally different.

This article is a practical introduction to Apache Beam from the perspective of a conventional backend engineer. Rather than focusing on APIs or syntax, it explains why Beam exists, how its execution model works under the hood, and what enables it to process enormous volumes of data reliably.

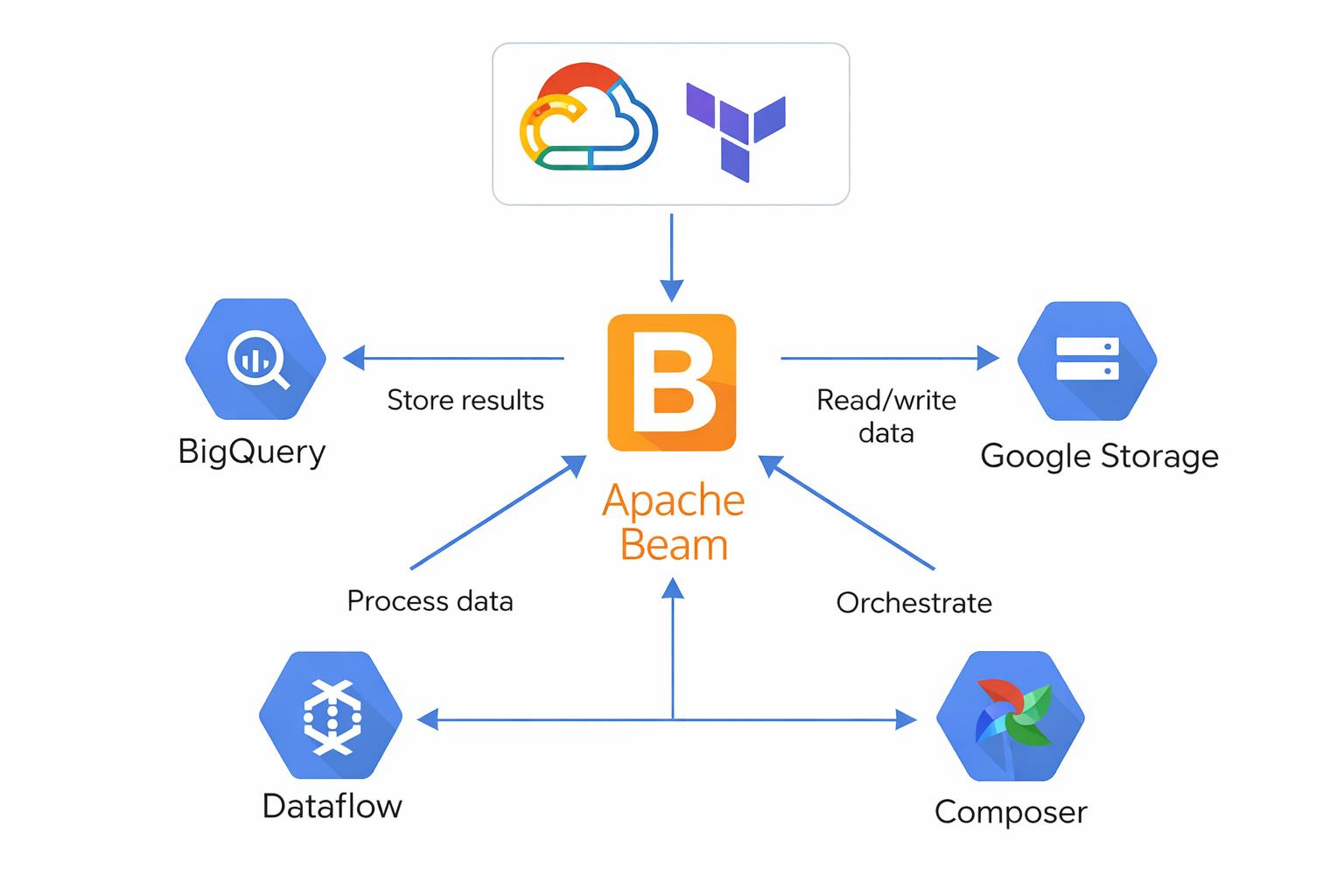

The discussion is intentionally GCP-focused, covering how Beam pipelines are executed on Dataflow, orchestrated with Cloud Composer, and provisioned using infrastructure-as-code. The goal is not to replace documentation, but to provide a conceptual bridge into the dataflow ecosystem—connecting familiar service-oriented thinking with the realities of large-scale, distributed data processing.

1. Why Apache Beam Exists (for REST API Engineers)

1.1 Request/response vs dataflow thinking

Most backend engineers start with a request/response mental model. A client sends a request, the server processes it synchronously or asynchronously, and a response is returned. Even when systems become distributed—behind load balancers, message queues, or service meshes—the core abstraction remains the same: a discrete interaction with a defined start and end.

Dataflow systems operate under a fundamentally different model. Instead of individual requests, they deal with continuous or bulk flows of data. There is often no single “caller” waiting for a response, and in many cases no clear notion of when processing is “finished.” Data arrives over time, possibly out of order, and computation progresses as data becomes available.

This difference is more conceptual than architectural:

- REST APIs think in transactions Data pipelines think in streams and transformations

- Services optimize for latency Pipelines optimize for throughput, correctness, and durability

Trying to reason about large-scale data processing using request/response abstractions quickly becomes limiting.

1.2 The problem Apache Beam was designed to solve

Apache Beam was created to address these limitations by introducing a unified programming model for data processing, independent of execution environment.

Instead of writing code that describes how data should be processed step by step, Beam encourages developers to focus on business domain and primarily describe:

- What transformations of data should happen

- How data flows between these transformations

- **What correctness guarantees are required

Key problems Beam explicitly targets:

- Processing massive datasets that do not fit in memory – think millions and millions of records

- Handling unbounded streams with late or out-of-order data

- Making computation reproducible and replayable

- Decoupling business logic from execution infrastructure

Crucially, Beam assumes that distribution, parallelism, retries, and failures are normal. Its abstractions are designed so that a pipeline can be executed across thousands of machines, restarted partially or fully, and still produce correct results.

For REST API engineers, this requires a shift in mindset: away from services responding to requests, and toward pipelines continuously transforming data. Beam exists to make that shift possible without forcing developers to manually manage the complexities of distributed execution.

2. Apache Beam Core Concepts

2.1 Pipelines as logical graphs

In Apache Beam, a Pipeline is not a program in the traditional sense. It is a logical description of a data processing graph. When you define a pipeline, you are not executing code; you are declaring how data should conceptually flow through a series of transformations.

This graph is directed and acyclic, commonly refered as DAG. Each node represents a transformation, and each edge represents a collection of data flowing between transformations. The pipeline definition is declarative: it specifies relationships and dependencies, not execution order or resource allocation.

A typical pipeline should look readable in code, and be domain centric:

Pipeline pipeline = Pipeline.create(options);

pipeline

.apply("ReadEvents",

PubsubIO.readStrings()

.fromSubscription("projects/my-project/subscriptions/iot-events"))

.apply("ParseJson",

MapElements.into(TypeDescriptors.kvs(TypeDescriptors.strings(), TypeDescriptors.strings()))

.via(EventParser::parse))

.apply("WindowByMinute",

Window.into(FixedWindows.of(Duration.standardMinutes(1))))

.apply("CountPerKey",

Count.perKey())

.apply("WriteToBigQuery",

BigQueryIO.<KV<String, Long>>write()

.to("my-project:analytics.iot_events")

.withFormatFunction(RowMapper::toTableRow)

.withWriteDisposition(BigQueryIO.Write.WriteDisposition.WRITE_APPEND));

pipeline.run();

For engineers used to imperative control flow—loops, conditionals, sequential method calls—this can feel unusual. In Beam, there is no guarantee that transformations will execute in the order they appear in code. The runner is free to reorder, fuse, parallelize, or split stages as long as the logical graph semantics are preserved.

This separation between definition and execution is what allows a single pipeline to run unchanged on different execution engines, from local runners to large-scale distributed systems.

2.2 PCollections: bounded and unbounded data

A PCollection represents a dataset in a pipeline, but it is not equivalent to a list, stream, or table. It is a logical abstraction of data, not a concrete in-memory structure.

PCollections come in two forms:

- Bounded PCollections, which have a finite size (for example, a batch read from files)

- Unbounded PCollections, which represent potentially infinite streams of data (for example, events from an IoT system) n

This distinction is critical. Many operations that are trivial on bounded data—such as global aggregation—are undefined or require additional constraints on unbounded data. Beam addresses this through concepts like windowing and triggers, but at the core level, the key idea is that data may never be “complete.”

Importantly, a PCollection does not imply where data is stored, how it is partitioned, or whether it is currently materialized. These details are intentionally hidden, allowing the runner to optimize data movement and storage transparently.

2.3 PTransforms: describing computation, not execution

A PTransform defines how input PCollections are converted into output PCollections. It describes what computation should be applied, not how it should be performed.

This distinction is subtle but fundamental. A PTransform:

- Does not control parallelism

- Does not manage threads or processes

- Does not dictate data locality

Instead, it declares a logical operation—such as mapping elements, grouping by key, or combining values—that the runner later translates into executable steps.

Because PTransforms are declarative, they can be analyzed, optimized, and rearranged by the runner. Multiple transforms may be fused together, executed remotely, or retried independently. From the developer’s perspective, this means writing code that is side-effect free and repeatable, even though it may execute many times across different machines.

2.4 Immutability, purity, and deterministic processing

Apache Beam relies heavily on immutability and functional-style processing. Once a PCollection is created, it is never modified. Each transform produces a new PCollection rather than altering existing data.

For this model to work, transforms must also be pure and deterministic. Given the same input, a transform should always produce the same output, without relying on external mutable state or time-dependent behavior.

In distributed systems, failures are expected. A transform may be executed multiple times, partially or fully, across different workers. Beam’s model assumes this and designs for it explicitly. Deterministic, side-effect-free computation is what allows pipelines to scale horizontally while remaining correct—even when processing massive datasets over long periods of time.

3. How a Beam Pipeline Executes on a Runner

3.1 What a Beam Runner actually does

In Apache Beam, a runner is not a library that “calls your code.” It is an execution engine that interprets a pipeline definition and turns it into a distributed computation. When you write a Beam pipeline, you are producing a portable, runner-agnostic description of a dataflow graph. The runner’s responsibility is to take that description and map it onto real infrastructure.

This distinction is critical. Beam itself does not decide:

- how many machines are used

- where data is stored

- how work is parallelized

- how failures are recovered

All of that is delegated to the runner. Beam defines semantics; the runner defines mechanics. This is why the same pipeline can execute locally, on a managed cloud service, or on a custom distributed system without changing application logic.

3.2 Pipeline translation and execution graphs

When a pipeline is submitted for execution, the runner first translates the logical pipeline graph into an execution graph. This graph is no longer a high-level description of transforms and collections, but a concrete plan composed of executable stages.

During this translation phase, the runner may break transforms into smaller executable units, reorder compatible operations, combine adjacent transforms or insert-shuffle the persistence boundaries.

The resulting execution graph often looks very different from the pipeline as written in code. ==This is intentional==. The logical graph expresses the human readable domain definitionas and the execution graph expresses efficient computation instructions.

This translation step is what enables Beam’s portability model. The same logical pipeline can result in different execution graphs depending on the runner, available resources, and configuration.

3.3 Serialization as a first-class concern

Once a pipeline is translated, the runner must distribute work across multiple machines. This immediately introduces a constraint that is easy to overlook: all user-defined logic and data must be serializable.

Beam does not execute your code in the same process where it is defined. Instead, it serializes user-defined functions, ships them to worker processes and finally deserializes and executes them remotely.

This means that serialization is not an implementation detail—it is a core part of the programming model. In fact having any of the objects not serializable will lead to runtime exeptions. Any object captured by a transform must be safely serializable and deterministic. Hidden dependencies on local state, thread-local variables, or non-serializable resources will fail at runtime or, worse, produce inconsistent results.

3.4 Coders and data movement between stages

To move data between stages in the execution graph, Beam relies on Coders. A coder defines how elements in a PCollection are encoded into bytes and decoded back into objects.

Every boundary in the execution graph—especially shuffles and repartitioning steps—requires data to be serialized. The choice of coder directly affects performance.

For simple types like String or Integer, Beam can infer coders automatically. For complex domain objects, custom coders are often required to ensure efficiency and correctness. Poorly defined coders can easily become a bottleneck, even if the transform logic itself is trivial.

Coders are one of the reasons Beam can process extremely large datasets: they provide a controlled, explicit contract for how data moves across machines and execution stages.

3.5 Coders vs Serializable

A common confusion point is the first glance similarities between these two.

Both Coders and Java’s Serializable exist because Apache Beam is distributed, but they solve different problems at different layers.

Serializable is about shipping code. Beam uses it to move user-defined logic—such as DoFns and their captured configuration—to remote worker JVMs. It answers the question: can this code and its state be sent to another process?

Coders are about shipping data. They define how elements in a PCollection are encoded to bytes and decoded again as data moves between pipeline stages, workers, and machines. Coders directly affect performance, memory usage, and shuffle cost

3.6 Fusion, sharding, and parallel execution

After translation, the runner applies optimizations to maximize throughput. One of the most important is fusion: combining multiple transforms into a single execution stage when possible. Fusion reduces unnecessary data materialization and network transfer, allowing elements to flow directly through several transforms in memory.

At the same time, the runner introduces sharding to parallelize work. Input data is split into independent shards, processed concurrently by multiple workers. As data flows through the pipeline, it may be repartitioned multiple times to balance load or satisfy grouping requirements.

These mechanisms work together:

-

Fusion minimizes overhead

-

Sharding maximizes parallelism

-

Retry and recomputation handle failures transparently

The result is a system where massive volumes of data can be processed efficiently without explicit threading, batching, or partitioning logic in user code. The developer describes what should happen; the runner continuously adapts how it happens at scale.

4 Apache Beam on Google Cloud

4.1 Executing pipelines on Google Cloud Dataflow

On Google Cloud, Apache Beam pipelines are most commonly executed using Google Cloud Dataflow. Dataflow is not a separate programming model; it is a fully managed runner that understands Beam’s execution semantics and provides the infrastructure required to run pipelines at scale. n

When a pipeline is submitted to Dataflow, the following happens at a high level:

- The Beam pipeline definition is translated into a Dataflow-specific execution plan

- Required artifacts (user code, dependencies, configuration) are staged

- Worker instances are provisioned dynamically

- The execution graph is deployed and started

From the developer’s perspective, the process is largely opaque by design. There is no need to manage clusters, provision machines, or handle worker placement. Dataflow abstracts these concerns away so that the pipeline definition remains focused on data transformation rather than infrastructure management.

This model aligns closely with Beam’s philosophy: the pipeline describes what should happen, while the runner decides how it happens in a concrete environment.

4.2 Autoscaling, worker lifecycles, and monitoring

One of the key advantages of running Beam pipelines on Dataflow is automatic resource management. Worker pools are not fixed in size. Instead, Dataflow continuously adjusts the number of workers.

Workers are treated as ephemeral execution units. They may be created, reused, or terminated at any point during pipeline execution. Pipelines are therefore expected to tolerate worker churn without relying on local state or long-lived processes.

Monitoring is an integral part of this lifecycle. Dataflow exposes detailed metrics, including:

- element throughput per stage

- watermark progression

- backlog size

- worker utilization

These metrics are not merely informational; they directly influence autoscaling decisions. Observability and execution are tightly coupled, allowing the system to adapt dynamically as workload characteristics change. For engineers used to manually scaling services, this represents a significant shift. Capacity planning becomes an ongoing, automated process rather than a static configuration.

4.3 Cost and performance considerations

Because Dataflow is fully managed, cost is primarily driven by resource usage over time rather than fixed infrastructure. Factors that influence cost include:

- number and type of workers

- execution duration

- data shuffle volume

- storage and network I/O

Pipeline design has a direct impact on both performance and cost. Inefficient coders, excessive shuffles, or poorly chosen windowing strategies can dramatically increase resource consumption. Conversely, well-fused pipelines with efficient serialization can process large volumes of data with minimal overhead.

This reinforces an important principle: while Dataflow removes much of the operational burden, it does not eliminate the need for thoughtful pipeline design.

5. Orchestrating Pipelines with Cloud Composer (Airflow)

5.1 Why orchestration is separate from execution

A common point of confusion when first working with Apache Beam is assuming that pipelines are responsible for when they run. In practice, Beam deliberately avoids this concern. A Beam pipeline defines how data is processed, not when or why execution starts.

Orchestration exists at a different layer.

On Google Cloud, this role is typically filled by Cloud Composer, which is built on Apache Airflow. Composer does not execute Beam pipelines itself. Instead, it coordinates their execution by triggering Dataflow jobs and reacting to their outcomes.

This separation of concerns is intentional. Beam focuses on data correctness and scalability, while Airflow focuses on workflow control. Conflating the two leads to pipelines that are harder to reason about, test, and operate.

5.2 Triggering and scheduling Beam pipelines

In a typical GCP setup, Beam pipelines are executed on Dataflow and triggered by Airflow tasks. These tasks may:

- start batch pipelines on a fixed schedule

- launch pipelines in response to external events

- coordinate pipeline execution with upstream and downstream systems

From Airflow’s perspective, a Beam pipeline is an external job with a well-defined lifecycle: submitted, running, succeeded, or failed. Airflow does not inspect pipeline internals; it treats Dataflow as an execution service.

For engineers familiar with cron jobs or ad-hoc scripts, this structured orchestration layer provides a more reliable and observable way to manage large-scale data workflows.

5.3 Managing dependencies, retries, and backfills

One of Airflow’s primary strengths is explicit dependency management. Complex data systems often involve multiple pipelines with ordering constraints, shared inputs, or downstream consumers. Airflow encodes these relationships directly in workflow definitions, making dependencies visible and auditable.

Retries are handled at the orchestration level rather than inside the pipeline. If a Dataflow job fails due to transient infrastructure issues, Airflow can retry the job without modifying pipeline code. This keeps error-handling logic centralized and consistent.

Backfills are another critical capability. When historical data needs to be reprocessed—due to schema changes, logic updates, or late-arriving data—Airflow can systematically re-run pipelines over past time ranges. Because Beam pipelines are deterministic and replayable by design, this approach scales far better than ad-hoc reprocessing scripts.

Together, these features allow Beam pipelines to operate as reliable, long-lived components in a larger data platform, rather than isolated batch jobs triggered manually.

6. Infrastructure as Code for Data Pipelines

6.1 Treating pipelines as reproducible infrastructure

At scale, data pipelines stop being “jobs” and start behaving like long-lived infrastructure. They have environments, dependencies, permissions, and operational requirements that evolve over time. Managing these concerns manually does not scale.

Infrastructure as Code (IaC) treats pipelines and their supporting services as versioned, reproducible artifacts. Instead of configuring environments through consoles or ad-hoc scripts, all resources are declared explicitly and stored alongside application code.

6.2 Provisioning Dataflow and Composer with Terraform

On Google Cloud, Dataflow and Cloud Composer are typically provisioned using Terraform. Terraform allows teams to define dataflow job configurations and templates, define Composer environments, create service accounts and permissions and configuring networking and storage dependencies.

By encoding these resources in Terraform, infrastructure becomes reviewable and testable. Changes to pipeline environments can be peer-reviewed in the same way as application code, reducing the risk of configuration drift or undocumented dependencies.

This approach also enables repeatable multi-environment setups. Development, staging, and production pipelines can share the same structure while differing only in controlled parameters, making promotion between environments predictable and low-risk.

A typical terraform script for defining a data pipeline in Terraform may looks something like:

resource "google_dataflow_job" "beam_pipeline" {

name = "example-beam-pipeline"

region = "europe-west1"

template_gcs_path = "gs://my-dataflow-bucket/templates/iot_pipeline"

temp_gcs_location = "gs://my-dataflow-bucket/temp"

parameters = {

inputSubscription = "projects/my-project/subscriptions/iot-events"

outputTable = "my-project:analytics.iot_events"

}

on_delete = "cancel"

}

6.3 IAM, networking, and environment isolation

Security and isolation are fundamental concerns in distributed data systems. Pipelines often process sensitive data and interact with multiple services, making fine-grained access control essential.

Using IaC, IAM roles and service accounts can be defined explicitly

Networking is treated similarly. Private service access, controlled egress, and environment-specific networks can be declared and enforced consistently. This prevents accidental cross-environment data access and simplifies compliance requirements.

Environment isolation completes the picture. Separate projects or environments for development, staging, and production ensure that experimentation and backfills do not interfere with critical workloads. When combined with Beam’s deterministic pipelines and Airflow’s orchestration, this results in data platforms that are not only scalable, but also auditable and operationally robust.

7. When Apache Beam Is the Right Tool (and When It Isn’t)

7.1 Suitable workloads

Apache Beam is well suited for problems where data volume, continuity, and correctness matter more than request latency. Typical examples include:

- Event and telemetry processing (IoT, logs, metrics)

- Stream and batch analytics over large datasets

- Data enrichment and transformation pipelines

- Reprocessing and backfills over historical data

- Systems where failures and retries must be handled transparently

Beam excels when computation must scale horizontally and remain deterministic under partial failures. Its model is particularly effective when the same logic needs to be applied consistently to both historical and real-time data, without duplicating implementation across separate systems.

In these cases, Beam’s declarative pipeline model provides clarity, portability, and operational robustness that are difficult to achieve with ad-hoc services or scripts.

7.2 Anti-patterns and common misuse cases

Despite its power, Apache Beam is not a general-purpose replacement for backend services. It is a poor fit for:

- Low-latency request/response APIs

- Interactive user-driven workflows

- CRUD-style business logic

- Tightly coupled transactional systems

Common misuse patterns include:

- Treating pipelines as long-running services with mutable state

- Embedding orchestration or scheduling logic inside transforms

- Relying on external side effects without idempotency guarantees

- Overusing Beam for problems better solved with simple batch jobs

These approaches conflict with Beam’s execution model and often lead to fragile, expensive, or hard-to-debug systems.

Conclusion: Moving from Services to Dataflows

Apache Beam requires a shift in how engineers think about computation. Instead of services reacting to individual requests, Beam encourages designing systems that continuously transform data flows under explicit correctness guarantees.

For engineers coming from a REST API background, this shift can be nontrivial. However, once the execution model is understood—particularly how runners, serialization, and orchestration work together—Beam becomes a powerful tool for building scalable and reliable data platforms.

In cloud environments such as Google Cloud, this approach integrates naturally with managed execution, orchestration, and infrastructure tooling. The result is not just better performance, but a more disciplined way of reasoning about large-scale data processing systems.