On October 16, the starry skies of the Canary Islands were illuminated by a spectacular fireball that crossed the sky from south to north. It was not a meteorite, it was a Chinese satellite that until a few days ago had been a complete mystery.

A mystery called XJY-7. Since its launch in December 2020, as part of the maiden flight of the Long March 8 rocket, the Xinjishu Yanzheng-7 had been an unknown. China officially described it as a “new technology verification satellite.”

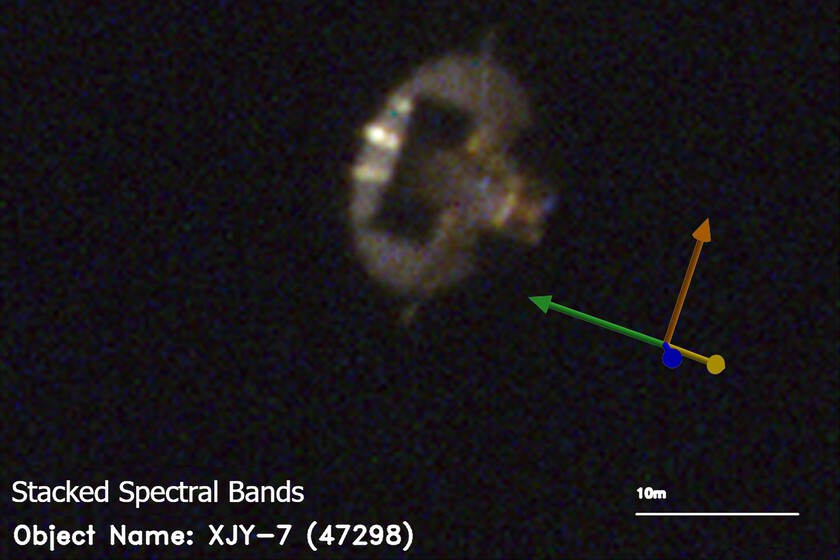

Aside from a blurry render, the world knew almost nothing about its configuration, purpose, or capabilities. And although its re-entry was news in itself, the real news is that, just before it disintegrated, an Australian company managed to photograph it in orbit, finally solving the mystery of what it was and what it was doing up there.

Counterespionage in orbit. Using its network of satellites to photograph other objects in orbit, the Australian company HEO achieved what ground-based radars could not: take photos of the XJY-7 up close.

The images and the 3D model that HEO built from them revealed features that China had neglected to mention. As the company stated to SpaceNews, the satellite was not a simple test platform; It was equipped with “a large radar antenna” and, most tellingly, a Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) antenna.

It was a spy satellite. SAR is an advanced remote sensing technology that allows high-resolution images of the Earth’s surface to be obtained in any weather conditions, day or night. The “mysterious” test satellite was, in reality, an advanced surveillance and remote sensing satellite.

The HEO observations also revealed a fascinating detail about its design: the satellite had fixed solar panels. This forced it to “rotate its entire body” to maintain power generation, a behavior that the Australian company was able to verify through multiple simultaneous observations from different angles.

Satellites that monitor satellites. Traditional monitoring methods (ground-based radars and telescopes) are no longer sufficient to monitor the activity of other nations in orbit. HEO uses a network of more than 40 in-flight sensors to take satellite-to-satellite images for its customers.

When one of its associated satellites passes near a target, it takes a photo of it. It is a “non-invasive flyby method” that offers real photographs where you can see antennas, panels, thrusters and payloads. With this technique, HEO has managed to identify more than 80 space objects before they appeared in any public catalogue.

In an environment where satellite constellations are deployed by the dozens, knowing whether an object is an operational satellite, a piece of space junk, or what type of antenna it carries is crucial for intelligence and defense.

Mysterious until his re-entry. Ironically, the mystery that surrounded XJY-7 in its useful life also accompanied it in its death, as the United States Space Command never issued a reentry alert.

This is “strange” for an object of this size, says expert Marco Langbroek. It is estimated that XJY-7 had a mass of between 3,000 and 5,000 kg. That an object weighing more than three tons bypassed re-entry warning systems highlights the gaps in conventional space tracking. Even worse when it comes to a satellite with secret capabilities.

Image | H.E.O.

In WorldOfSoftware | Two Chinese satellites have found themselves in space. For the US, things are clear: they are a direct threat