In 2019 researchers at Berlin’s Computer Games Museum made an extraordinary discovery: a rudimentary Pong console, made from salvaged electronics and plastic soap-box enclosures for joysticks. The beige rectangular tupperware that contained its wires would, when connected to a TV by the aerial, bring a serviceable Pong copy to the screen.

At the time, they thought the home-brewed device was a singular example of ingenuity behind the iron curtain. But earlier this year they found another Seifendosen-Pong (“soap-box Pong”), along with a copy of a state-produced magazine called FunkAmateur containing schematics for a DIY variety of Atari’s 1970s gaming sensation.

The discovery rubbed up against received wisdom that the dawn of computer gaming had at best been tolerated and at worst suppressed by socialist East Germany. Instead, here was evidence that gaming enjoyed a level of official support, including from the regime’s notorious secret service.

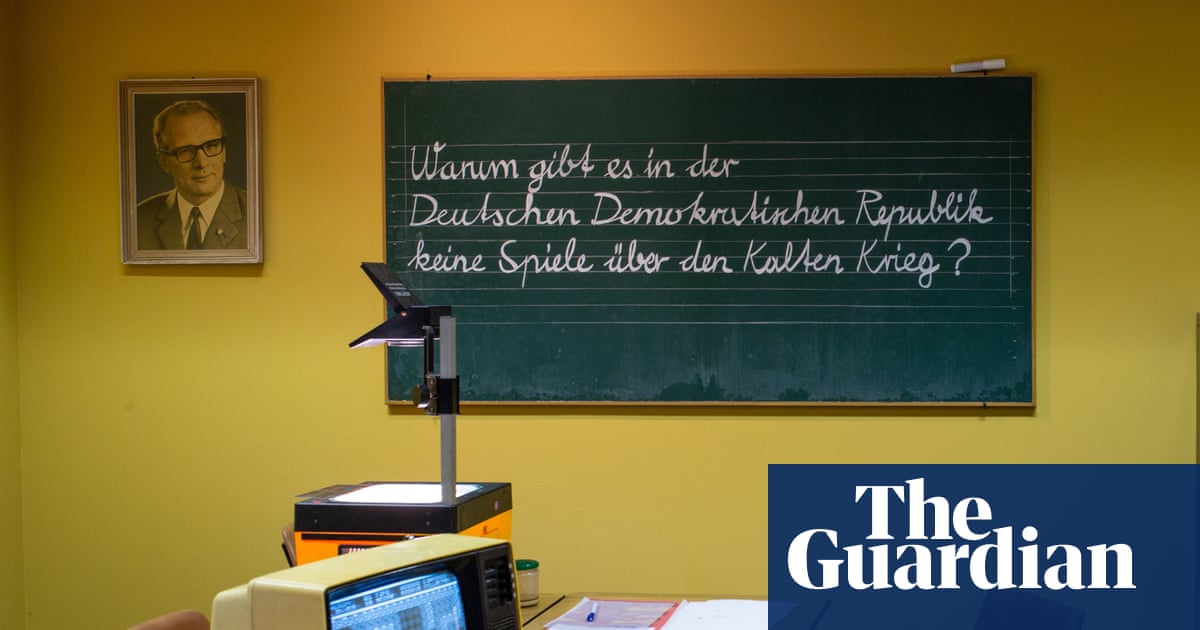

A new joint exhibit from the Allied Museum and the Computer Games Museum in Berlin brings cold war gaming curios from both sides of the iron curtain to light, including East Germany’s only arcade cabinet, the Poly-Play, which visitors can try out. With honey-coloured wooden panels and a brightly lit typeface, only 2,000 of the machines were made. In the late 80s, adolescents would crowd the cabinets at youth clubs and holiday retreats, to the extent they were available, where they could play a number of games cloned from western originals.

But the Poly-Play “was only possible with help from state security,” says Veit Lehmann of the Allied Museum. Lacking programming expertise and manpower, manufacturer VEB Polytechnick turned to the Stasi for help. They were the ones with “the experts and the computing capability” to code the games.

Instead of Pac–Man, there was Hase and Wolf , a canine-dodging hare swapped for Namco’s famous cheese-wheel-shaped ghost-evader. There was Hirschjagd (“Deer Hunt”), a repackaged take on the sci-fi shooter Robotron: 2084, There was Schießbude, a copy of a carnival shooting game; a butterfly-collecting title called Schmetterling, a memory puzzler; a skiing game and a racing game among the rest.

The Poly-Play was many East Germans’ first encounter with computers, and it “opened up a completely different world for them”, says Regina Seiwald at the University of Birmingham. “The Poly-Play was seen as a machine for the whole family, who’d enjoy a weekend, go for a walk and then jointly play on one. It was seen as an innocent pastime, but with a bit of technical skills training added in.”

But, as arcade-goers in the west commandeered tanks in Battlezone or blasted dragons from jetpack-propelled gunners in Space Harrier, the Poly-Play had all notions of violence removed. The GDR liked to present itself as an idyllic, peace-loving state, and its media law deemed all forms of “calls to violence” unconstitutional. “The GDR’s attitude toward computers was an idea of a harmonic self-image and a fear of the unknown,” Seiwald says.

Yet, away from the Poly-Play and its PG approach to gaming, self-described “freaks” gathered at computer clubs to test the tolerance of the police state. The east declared technology an economic priority in the late 1970s but, with the CoCom trade embargo blocking exports to the socialist bloc, western technology was only available through smuggling. routes, with ZX Spectrums sewn into car seats or hidden in chocolate boxes for cross-border journeys.

State factories did produce their own machines – such as the Bildschimmerspiel 01 pong clone and the VEB Robotron series of microcomputers – but only in small numbers. High price tags made them unattainable for most.

As early enthusiasts began to establish clubs at universities and youth centers from Berlin to Dresden and Leipzig, the state wondered if this youthful interest could help carve a path out of its technical quandary. “They thought if young people spent their time with games and computers, they might develop something better,” says Lehmann. Perhaps, the state thought, this interest could stir new generations into careers in microelectronics, where they might develop much-needed homegrown chips.

An oft-repeated phrase among GDR officials, adds Martin Görlich, managing director of the Computer Games Museum, was that “learning from the Soviet Union means learning how to win”. So embracing computing echoed the position of the USSR, which also had arcade games – Frankenstein-like hybrids that blended physical action with screens – and ran its own computer clubs.

Of course, the USSR also gave birth to Tetris, the fast-paced puzzler designed by software engineer Alexey Pajitnov to test a new computer. (The game was initially traded between engineers, but led to a dramatic race to secure distribution rights from the Soviet Union between Dutch-born game designer Henk Rogers and Kevin Maxwell, son of disgraced media mogul Robert Maxwell.)

Over in East Germany, citizens often relied on bootlegs to get around restrictions or shortages. Would-be fashionistas stitched their own clothes, musicians cobbled together audio equipment, and enterprising sorts of hand-painted banned board games such as Monopoly, with Mayfair swapped for Karl-Marx-Allee and a party conference square taking the place of jail.

A DIY approach to computing was thus in keeping with the state’s policy of self-reliance, where civilians were encouraged to knit, build, tinker and repair all they could. Official magazines such as FunkAmateur and Jugend und Technik responded by promoting games – which they called “computer sports” – and publishing programming code. “The GDR was very aware of the constraints it had in technology,” says Seiwald. “People educating themselves in technology, or pushing the boundaries of what was available, was viewed positively.”

Tantalizingly for young hobbyists, some of the domestic computer clubs, such as the House of Young Talents in ast Berlin, possessed much-desired Commodore 64 machines, which were far superior to the GDR’s equivalents. Most club attendees were young and male and, unsurprisingly, interested in games above all else.

Some learned to code their own games on state computers such as the KC 85 by VEB Mikroelektronik, while others played them, such as René Meyer, who was 16 when he was introduced to a computer club at the University of Leipzig.

“The GDR’s home computers were not compatible with other systems, creating a unique ecosystem for computing in the east,” says Meyer, whose favorite game was Bennion Geppy, its hero tasked with traversing dungeon rooms, dodging monsters and collecting keys.

Paradoxically, while the state seemed to support these groups – club-goers were sometimes rewarded with fast-tracked routes to engineering colleges – they were also infiltrated by Stasi informants and closely monitored, their computing activities regarded with suspicion. One report from the Stasi archive lists all the games in circulation at the House of Young Talent. Next to acceptable titles such as Superbowl and Samantha Fox Strip Poker, games such as Rambo and Stryker were singled out for their glorification of violence.

Later, as internal conflicts within East German society intensified, the Stasi grew more paranoid about war-themed games, computer viruses and anti-socialist messaging in software. Perhaps their fears weren’t unfounded: in neighboring Czechoslovakia, underground gamers programmed titles such as The Adventures of Indiana Jones in Wenceslas Square, a text adventure where the The fedora-decked explorer could meet a grisly fate at the hands of bloodthirsty police officers.

The east wasn’t alone in its mistrust of technology. In 1984, West Germany banned children from playing arcade games, concerned that they encouraged gambling. Then, it introduced strict age-gating for supposedly violent games, such as the Activision title, River Raid. This suspicion around gaming extends well into the 21st century: publishers have had to alter the content of their titles to get around censor boards. Players of the German version of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, for example, were punished with failure if they shot civilians in its notorious ‘No Russian’ mission, where terrorists massacred travelers at a Moscow airport.

While East Germany promoted decentralized computing, over in the west, the state held a firm monopoly on telecoms, criminalizing home networking and especially hacking. In the 1980s, activists in West Germany responded by founding the Chaos Computer Club, which continues to this day, even creating a DIY modem from toilet pipes in protest: the Datenklo (“dataloo”).

“The West was very harsh in punishing hackers and crackers,” says Seiwald. “That the GDR was more permissive surprises a lot of people.”