Transcript

Jade Abbott: My name is Jade. I’m the CTO of Lelapa AI. We are an African language AI startup. Been around for around two years. Just getting towards the end of our seed funding and busy raising a Series A. Also, in 2018 or so, started a research foundation called Masakhane. I say research foundation, but back then it was just a vagabond group of researchers from across the African continent. We came together because we realized that none of the language tools, even back then, were supporting our languages.

By day, at least for many years, I was an ML engineer. Been doing it for over a decade. I’ve been putting in machine learning models into production like pre-TensorFlow. I can’t even remember. It was like a Stanford library that they had built, trying to ship that to production was one of the most horrifying things. As you know, we’ve actually had language models since the ’80s. We’ve just been iterating on them and making them bigger and stranger and more powerful.

Where do I come from? I am South African. I come from the majority world, which is where the majority of the population lives, aka the global south. Particularly, I’m from Africa. There are over a billion people. What’s really interesting is it is the youngest population in the world. By 2050, I think a third of the world is going to be African. What’s also interesting about Africa is it has over 2,000 languages, many of these spoken by millions of people. For maybe some of the countries you might know of quite well, South Africans, 9 out of 10 of them do not speak English at home. Nine out of 10 Nigerians do not speak English at home. Over 250 million people speak Swahili as their primary language. The numbers we’re talking about are actually quite massive here.

Another thing about where I come from is, in Africa, we’ve got a mobile penetration rate of 82%. It’s surprisingly, in some of the countries, some of the highest in the world. The way that many countries in the west have gone through the phases of first, you get a computer. Then eventually, there was a laptop. Eventually, it came to a phone. A lot of the people went straight into getting affordable phones, affordable smartphones, in many cases. Counter to that, 43% of the continent actually lacks consistent access to electricity. Immediately, we’re here with a huge major constraint. Up until quite recently, there were only three data centers or publicly available data centers that anyone could access, with GPUs, on the continent. As we all know GPUs are the power. If we don’t have that, what are we meant to do?

Can ChatGPT Speak isiZulu?

A couple years ago, to really contextualize the problem is isiZulu is a language spoken by 11 million people in South Africa. It’s got a whole bunch of related languages, also spoken by millions of people across. You don’t even have to know anything about Zulu to know this is probably wrong. We asked it to count from 1 to 10. It went Ku-one, Ku-two, Ku-three, Ku-four. We made a big public fuss about it. This has since been fixed. I think they got a bit embarrassed that Zulu is doing substantially better. This one I also thought was really fun. Here we’ve got an original sentence, which usually I like to say and embarrass myself with my terrible Zulu. Yes, you guys wouldn’t know, probably. I’ll skip that. Instead, just focus on the target translation. This is what a human translated it at. I feel like there could be more to help people with this industry. Very standard. M2M100, which is an open-source model trained by Masakhane, focused on centering African data, centering African models, said, “I see there’s a lot you can do to help people at this establishment”. That seems pretty equivalent. I’d be happy with that as a translation.

Then, GPT-3.5, back in the day, said, “I skipped around trying to use as much plant material as I could”. I think it’s probably my favorite genre of anything related to LLMs is actually when it does very strange things like this. isiZulu being spoken by 11 million people and being quite well supported in South Africa, it’s actually one of the languages that has more resources than maybe some of the others. It doesn’t quite reach the level of data that we’ve got. It never will. Eighty-nine percent of the internet is in English, and usually white, most of them male. Where exactly are we getting our data to train all our cool language technologies?

Sustainability

This talk is really about sustainability. A lot of what we do is really framed around the idea of sustainability. What’s interesting is different parts of the world and different people have different perspective of what sustainability is. I think one that we are all very aware of is the environmental sustainability. That is the one we’re probably talking about most often. Something that’s really relevant in the majority world is something called economic sustainability, which is being able to be robust to the global market forces and not be reliant on them. Because they can devastate nations.

Then, lastly, cultural sustainability. In the UK, it’s one of the most prevalent cultures in the world, abiding by many Western narratives. We’ve got over 2,000 languages that could be conceptually over 2,000 ways of thinking. How are we enabling those diverse ways of thinking, those diverse ways of approaching problems to flourish? I’m going to go through each of these and just talk about some of the issues that arise doing AI in these areas. At the end, I’ll come together and we’ll talk about how we can make it better.

Environmental Sustainability in AI

Environmental sustainability. Everyone got on this trend. How many people made a Ghibli version of their whatever it was? This was really cute. They butchered our logo. We took a photo. We showed it. This is the founders of the organization at Lelapa. Everyone was like, cute, cute, cute. Then I saw this really fun tweet. I love watching Sam Altman these days. I resonate a lot with what he’s going through. He says, love seeing people put images into ChatGPT, but our GPUs are melting. They had to basically put on some rate limits. I really want to hone in on, our GPUs are melting. We are just essentially messing around, having fun, doing something silly, and we’re literally just burning energy. Thankfully, there are a lot of wonderful researchers who have been working on this topic for quite a while, even pre-LLM era, and been evaluating the environmental impact of AI models. I might start with some of the obvious things. It’s like, when something’s running, how much energy is it taking? That’s your most basic one.

Then also when it’s not running, when it was training, how much did it take to train? What we also failed to encounter is all those failed training attempts. Anyone who’s trained an AI model knows you never do it once. You start it, you realize halfway through something’s wrong, and then you stop it. Or it crashes and you’ve spent three days training it and now you have to retrain it again. Or you train it completely and at the end of it you look at it and it’s simply not good enough, and you have to go and redo the entire thing due to some small processing error. The amount of failures that happen is very high. This just digs back even deeper actually to the entire pipeline. What we realize is that pretty much the entire pipeline of AI is riddled with a whole bunch of climate issues and environmental issues.

I come from Johannesburg, which is one of the big cities in South Africa. We have a problem in South Africa where we cannot match our electricity supply. We have lots of people, very fast-growing population, and we just haven’t been able to keep up and maintain our electricity. What this means is we have this really cute thing called load shedding, which means we know at certain hours in different regions, they’ve even built a little app for it, you get a notification saying you will not have electricity for 4 hours because there’s less load available. There could be many reasons. Some generator’s gone down. You get quite specific notifications about what’s going on. I say it’s cute because we see it as sharing. You get to have some electricity and then the next suburb next to you gets some electricity and the next suburb next to you. Given we’re talking about places that can’t sustain their own electricity, how many Johannesburg homes could one training of a GPT-3 model power for a month? Isn’t that depressing?

Then we think about ourselves and every single person and their neighbor wants to train their own version of this. It just at some stage became this peacocking of how big a model we could run on our cluster and how advanced we could get it. More than electricity is cooling data centers takes a lot of water. Ten to 50 queries on GPT-3, once again, these are a bit older. What we really don’t have numbers on is whether they got more or less efficient. No one’s reporting on it, or detailed reporting on it yet. They’ve estimated that it uses half a liter of water for every 10 to 50 queries. I myself use 10 to 50 queries on GPT models every day. I imagine a lot of us who are quite active in our use of these tools are doing so. That doesn’t even account for all the other things that we’re not looking at.

I think one that really touches close to home and we’ll come back to in this conversation a bit later is the minerals that go into building the GPUs. A lot of these are what we call conflict minerals. They’re rare minerals that only occur in certain regions on the continent or certain regions in the world. What happens is war builds up around those minerals because they’re so hard to access. They’re so valuable. DRC Congo is a really terrifying example of what happens with conflict minerals. Many of these things that are used to build GPUs, to build our phones, are involved in those pipelines. You can see some of the GPU providers, they have some attempt to try vet their procurement pipeline to figure out if they are getting them sustainably. We know those processes are often riddled with issues.

Economic Sustainability in AI

We’ve covered a little bit of how AI can completely, potentially wreck sustainable ecologies. Now we’ll move on to the economic sustainability question. This became really stark very recently. I think we all know about this particular issue, where the USA dropped funding. This is a very recent survey from a month ago. It had a number of stats, but I actually found some of the reports from some of the people who were working on the ground. This is due to the fact that a lot of aid in the world is not built sustainably. The models in which we use, even to help other nations or to have nations help us, sustainability actually isn’t part of the question. What happens is there’s some political something or another, and countries just decide to cut off that funding.

That cuts off basic access to health care, basic access to food, basic access to support for mothers, to support for people who are subjected to violence. This is very tangible. We are feeling it very real at this moment. I’ve got many friends who work in such spaces where there has been funding cuts, and they are affected. They are working aligned to governments and really helping to aid them. This idea of, how can we make these more sustainable when 90% of African NGOs rely on international funding? For me, you can’t actually rely on NGOs for funding. I think there’s a big perception of as soon as you’re talking about Africa or the majority world, you’re talking about a place that needs donations, a place that needs giving. We need to figure out what we’re deciding to give it to, our cause, and how it’s going to work.

Actually, that’s completely unsustainable. Because right now, a whole number of countries are retracting their development funding that they were sending to parts of the world. What we actually need is a sustainable business. That’s a very different approach. It’s really thinking more in our product minds of, how are we actually long-term solving a need? Thinking about this initial money that comes in from an NGO as an investment to a sustainable process. I don’t think many organizations have done that. I mentioned earlier how I helped found Masakhane Research Foundation. I found the process of funding that so painful that a group of us decided to actually make a startup because it moved faster. That’s the reality we live in. We need sustainable business.

Then we go into the economics of language itself. I said there are over 2,000 languages in Africa. There are over 6,000 languages in the world. We have a couple of concepts which are very interesting. One of them is the concept of linguistic justice. If an organization is deciding what tools they’re going to build, the number of people speaking your language, or even not just the number of people, but their economic situation dictates whether they’ll get tools built for them. Arguably, we’re talking about all these generative tools as a means to say, let’s build things for education. It’s got to solve education. It’s got to solve health care in all these parts of the world. It’s going to transform everything. It’s not going to do it if we’re actually not able to communicate with people in their own language. We’ve got all these really high expectations. We need to really consider what linguistic justice means and achieving that means.

As soon as you have this issue where services aren’t provided in those languages, it results in this massive digital divide. The digital divide here is people don’t have access to not even the new LLMs, they don’t have access to some of the basic services. They don’t have access to the basic business. There’s this really strange thing that happens in trade. If you don’t speak the same language, they call it a border effect. It’s almost as if there is an artificial border between these nations because they’re not speaking the same languages. You get this idea of the smaller languages or the ones that bring in less money get left behind. Typically, when you look at the AI startups of the world, is they’re really focusing on that 1%. It’s a large amount of population. It’s probably around five or six languages. It covers a large percent of the population. It’s still only half. To get to the other half, there’s a lot more work that needs to be done and a lot more changes in the way we need to think about it. Some organizations have done a lot better, at least thinking more broadly. Often, they’re not solving the solution.

My last thing on this economic thing, again, is coming back. I’ve got the same picture for a very good reason. I was talking about conflict minerals. It’s often due to this process of being on the continent. What we see is a lot of extraction of raw minerals. We’ve seen it for decades, longer. Extraction of raw minerals, of gold, of platinum, of cobalt, all these really important minerals, they get extracted and then they get refined elsewhere and built into products and then sold back to Africa. The people who are really profiting, getting the biggest markups, are the external organizations from other parts of the world rather than the African countries themselves.

This idea of data as being like a raw material, data is a mineral in many ways, the thing we build our AI upon, most of AI has really seen it as this extractive process. It’s, there is data, we will find it and we will take it. Sometimes we will make a big fuss about making sure that we’re on the right side of the law and we’ll get all these lawyers to back it up, and we’ll create motivations and they’ll have all these crazy cases. There’ve been a number, if you’ve been following, with OpenAI and a number of other organizations, whether it be stealing art, whether it be stealing literature to actually do this. We’ve been trying to move away from extraction. If you look at the majority world, a lot of them are bringing those refining processes back closer to the mine so that the populations here can benefit. Similarly, we need to think of something around data like that.

Cultural Sustainability of AI

My last point is cultural sustainability of AI. A language dies approximately every two weeks and with it dies a way of thinking. What this slide spoke to is that different languages have different ways of talking about things. They’ve got different levels of depth. They’ve got different levels of something as simple as time. Time gets perceived from a left to right sense in English. In Hebrew, it’s a right to left sense based on their reading.

In Chinese, it’s actually down to up. We have different breakdowns of that, for example. In South Africa, we’ve got this really cute thing where we say now, and now-now, and just now. Those are three different meanings. If you know any, you might have experienced it. Now means now. Now-now means like maybe next 5 to 15 minutes. Just now could be anything from 5 minutes to the next 4 hours, we don’t know. When you have the tangible words for something, you can explore concepts in a completely different way. This value of having these different ways of thinking really allows a greater collective intelligence to emerge. There’s this massive study from McKinsey many years ago that said diversity breeds better solutions and better productivity by quite a significant percent. This is really talking to that, like the value of preserving culture. What AI does is it creates a hegemonic society. It’s basically taking what’s already available, which is already biased by the powers that be in the world.

As I said, over 89% of the world speaks English, and it’s usually white male and American who are participating in that discourse. It creates an average over all of those. That’s essentially, we’re just making an average machine. They might improve in certain ways and we can bias them and we can curate them. At the end of the day, they’re still representing a hegemonic view. They’re still representing a major viewpoint. That’s something to keep in mind is that AI is not actually just a science, it’s a social science. I think that, at least, discussion is becoming more prevalent over time.

What Does a More Sustainable World Look Like?

I’ve listed a lot of problems. Hopefully we can now see these three different types of sustainability and how they might fit in. What does a more sustainable world look like? One of the big things, and we’ve started to see this trend happening, is instead of making them larger, we make them littler. You can see this with many processes. Initially, there’s a big thing, it becomes really inefficient, but it needs to solve the problem. Over time, we need to start drilling out those inefficiencies. Instead of LLMs, we have big L, some people say SLMs, small language models, which is all relative. We like to call it little LMs, so with a small l. Is bigger always better? The answer is now astoundingly or resoundingly coming out as very clearly no. We don’t have to use more resources. We don’t have to make the models bigger to make them better. In fact, we can get so many gains by making them smaller. Your size of your bubbles is the size of your models. You can start to see that up your y-axis, you’ve got performance on a particular dataset called MMLU. It’s one of the math reasoning ones. You can see that the models are starting to get smaller and are starting to beat the performance of some of the bigger models.

For us on the continent, while a lot of the organizations building these LLMs were growing exponentially to get these tiny improvements, I think that’s something that’s also quite clear, is even if you’re making it bigger, you’re not necessarily getting large performance gains anymore. Lelapa we’re really focused on, how can we make something as small as possible? We trained a Little LM, we called it Inkuba. Inkuba is the Zulu word for dung beetle. A dung beetle is a really cool animal in that it’s really small. It can move up to 100 times its weight. From this little bug, it moves this really large ball. That’s the idea and the metaphor we wanted to go with. Here we really focused on, we only have so much data. We only have so much compute. What is the most efficient way we can train a model?

On a number of tasks, we found that despite it being an order of magnitude smaller almost, we were able to perform comparatively well on some tasks. This is kind of people are following with us. Aidan Gomez, who’s CEO of Cohere, they’re another one of the big LLM companies, along with Anthropic and OpenAI, says it’s not about unlimited resources, but smart, efficient solutions. I’m talking a lot about the majority world, and I’m talking a lot about Africa here, but anyone who’s tried to run an LLM in production or train one themselves knows the amount of cost that goes into actually doing it, and knows the amount of cost it takes to actually run that, even if you’re optimizing everything to run as efficiently as possible. This doesn’t just benefit us, but it actually benefits the whole world to know how to do this better.

A lot of the things that I’ve mentioned, as we can see, they’re actually outside of the code themselves. It’s outside of what we might see as the things we can champion within our organizations. Still, we should take that step back to say, how can we work on the greater picture, and what can we do? While we’re doing that, we know that people, this is a much slower process to move than code. What are the things we can do to make it littler? One of the most successful things of recent time is called model distillation.

The idea, you have a teacher or an oracle, and that’s your big model. Could be any one of the pre-trained ones that already exists. We’re not adding extra training, we’re not using extra compute, we’re using something that someone has very cleverly made open source for the rest of us. You can train a student model. The student model is much smaller. That means it uses less memory. That means it uses less energy to run. This means it can run on smaller devices and ultimately makes it more accessible. Model distillation is quite like an extremely successful approach. It’s one of the things that really gave DeepSeek the boost was they just distilled the model against, there were arguments about whether it was OpenAI or not. Things like that have happened. Yes, it is what it is.

The other one, and this is also once more on the inference side, is about making it littler to run. Because the training is a lot, but running them is a lot, particularly at scale. The silliest way you can do is something called quantization, and it’s really astounding that this works, is it turns out if you just chop a bunch of the bits off, when you do a little small transformation to make sure that actually, instead of fitting into 32-bit floating point and fitting it into like an 8-bit int, you actually can still retain a lot of the power. The difference in actual ability and performance from an accuracy perspective and from a quality perspective doesn’t drop that much. What you do get is substantial speed, performance, memory gains, which means we can start running these on less intensive hardware. We also get the side benefit is that it runs a lot faster.

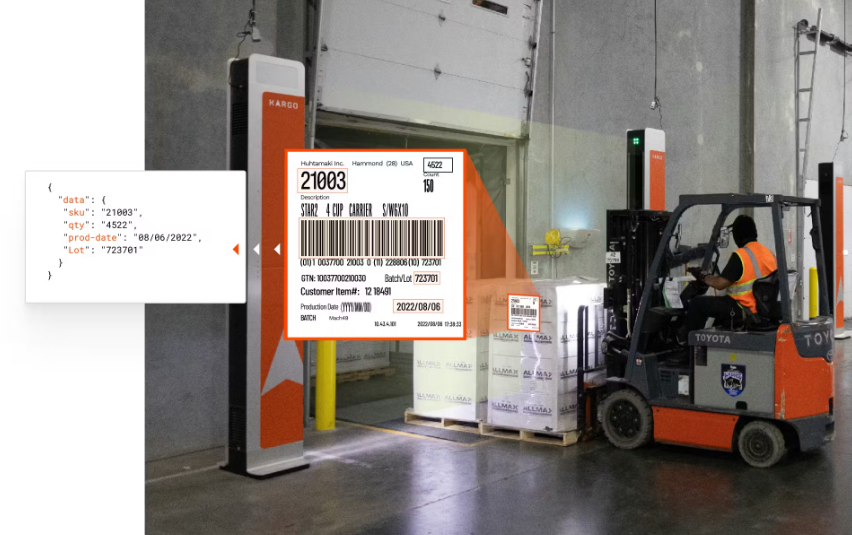

This, at many organizations, has become standard practice. It’s part of the process. If you’ve trained an AI model that’s in the deep learning space, you quantize it before you deploy it. It must be done. It’s a step in the process of quantize, check if the performance is within range, and then deploy it, because you’re just going to get something that works a lot better. Just for some people who want to see some code, that’s five lines of Hugging Face. It’s nothing. That will quantize it pretty well. There’s even faster ones to do it, even less lines of code. Not that we care too much about that. What I’m saying is that this has been built into the framework because it is so useful and it’s something we should use.

When it comes to training, training with memory, we know the machines get really big. If you have less memory, you can also fit more into the GPU, which means you can train it faster, which means you can get it out the way, and the training done quicker, which ultimately means we spend less. There’s a technique called LoRA. What this does is it actually looks a bit deeper at how we’re doing weight updates on our models. LLMs are just basically a collection of matrices, gigantic 3 and D vectors which we multiply together. If you remember anything from back in the day when we might have been doing some math, you can do a bunch of things by actually decreasing the dimensionality cleverly of a single matrix into two smaller matrices. By doing that, you’re updating a lot less parameters. This allows you to train with a lot less memory and a lot faster.

Then, the last innovation that’s happened quite recently is GRPO, which is Group Relative Policy Optimization. Also, once again, this is one of the big revolutions of DeepSeek. This comes from reinforcement learning. It is quite a complex process. To boil it down is, back in reinforcement learning, you used to have two versions of a model. You had the actor and the critic. The critic was the one that decides how well the policy that was applied by the actor was done. Typically, it’s the same size as the actor model. What you’re doing is decreasing your memory and compute by almost half.

Additionally, what it does is it allows you to evaluate without target data. For each input, what they do is they generate a set of responses, then they, instead of evaluating it against an external critic model that’s meant to come and evaluate these, they self-evaluate within that little set of responses. This evaluation is done relative to each other, and that feeds back into the training of the model. Just by doing this critic-free optimization, not only can we reduce the compute and memory by a half, we can also really improve the data usage and data needs that they need to have. This was one of the really impressive optimizations that they did in DeepSeek.

A Focus on Human Centricity

I think this is a key thing in my life is this focus on human centricity. We know that code is actually people. We know that AI is actually people, maybe even more so because of the data that gets used to train it. What does human centricity mean beyond just the code that we’re writing and the bias and the things that we need to be taking care of? This is talking to the sustainable economics, is instead of this data extraction process which I referred to earlier, this raw material we’re extracting from people and selling them back the finished product, how are we developing a sustainable ecosystem around creating data? Instead of scraping it, let’s make it. What’s nice about when you make it, you make it fit for purpose. You create it for the population that will use it and not try to adjust what’s already there to malfit it. What happens with the LLMs is that they take whatever is available, we shove that in, and then we hope it doesn’t say horrible things. When it does, we try to put blockers against that. We might try to curate the data. Some people have had really good progress on that.

For us, what we see is, let’s focus on data creation. How are we funding organizations, people creating these organizations that become data creators? Because unlike minerals, we are the creators of data. How can we build sustainable economies and businesses around that? We recently published something called the Esethu Framework, which is a set of sustainable governance frameworks for curation and low resource languages. Out of it came a couple of things. One of them was this very basic process of just this idea of creation. Pay someone to create for the need. What are we solving for? We are solving for health care in this region for these people. Let’s go speak to them, create an organization around them which can sustainably fund the creation of more data. What was really cool in this experiment is we started with a very small dataset, that was paid for by us. It was actually something that we collectively worked together on.

Then showed how well just 10 hours of data, so this is for a speech model, 10 hours of data could significantly improve the model. As people then licensed that data for a small fee, we were able to show that if you reinvest those funds, you can start hiring people full time to start creating that data. What this picture shows is that after a couple of months, we’re able to hire a full-time transcriber. We’ve captured 100 voices. After a couple more months, we’re able to hire two transcribers. After even more months, we’re able to hire four transcribers. What’s also really interesting is that there’s a big push for open source. Open data comes with a little bit more constraints, because then who owns that data? Open source, we knew who created it, they get attribution. Open data, there were lots of people who went into creating it, not just the people who put it together. With this particular study, we decided to do something quite lovely, I like it, is we amended a license. We say it’s open source for research, this is one of the Creative Commons licenses.

Then amended it with a particular clause, that said, for African institutions, we’ll grant it for commercial license for free. For non-African institutions, we require a commercial license. Then we refer people to the commercial license. What this does is really help the ecosystem. One of the fears a lot of people have is, is this actually going to be used to benefit me? Is it an extractive to sell the product back to me? This is how we make sure it stays within the context and the continent and the ecosystem that we care about. We want everyone to benefit from what we build, the same way that we do with open source. We know that there are many people who have a lot more power and a lot more compute and a lot more energy. If they decided that they wanted to come and invade Africa and take everything we’ve got and sell it back to us, they would. Just like they’ve done for thousands of years.

Last one, and this is easy but so surprisingly important, is transparency. If you are in the model building game or you’re in the model selecting procurement game, you want to be talking about model cards. Model cards are a transparency mechanism invented by Timnit Gebru and Margaret Mitchell. What they basically said is that each time you’re running something, you should know what it is you’re running. By that you should know what data it was trained on, at least a general description. It should outline its uses, what was it trained for. It should outline cases where it should not be used. It should outline what the process was for curating the data that went into it. It should outline a whole bunch of things which help you evaluate better if this model should be used in the place that it should be.

Additionally, in reporting that, it also creates a perfect space to start reporting on your climate impacts. There’s a number of emissions calculators. I quite like this one. It allows you to specify exactly what cloud you’re working on, because they obviously have their own green capabilities. How many hours of compute, what device it was, and then it gives you an estimate of what your impact was. That is something that you can include in your model cards. Additionally, when you’re evaluating models and what to use, you can ask them for these model cards and you can ask them for these metrics. They often have teams working on them, but they’re not necessarily publishing them. It’s up to us to really ask our providers to supply these things.

Then, lastly, it’s a big call to never stop envisioning the future we want. We are moving, flailing, driving, speeding, sprinting towards our dystopian cyberpunk nightmare. Every day it feels a little bit more and more like that. Cyberpunk is this high tech, low life, is that we have technology to do wonderful things, but actually we lead a very low quality of life. Whereas actually what we want is high tech, high life. What does that look like? I think one of the problems we have is when we’re in the space, we know we’re trying to improve our metrics, we’re trying to do this, we’re trying to do that, but we’re not necessarily united by what it is we’re building. Like, where are we going? This we call to artists, we call to the sci-fi writers who build these things, to say, what is the future we actually want to build? Because then we can start crafting it. We worked on a little zine, which you can access at the link there, https://lelapa.ai/lelapa-ai-zines/. It’s just on the Lelapa website, where we propose UBUNTU PUNK. Ubuntu is a philosophy from Africa, which states that I am through you.

My identity is through the people around me. Instead of individualism, which is what a lot of the West bases its philosophies on, and you can see this in the way that we work with money, we can see it in the way that we form societies, the way we form unit families, the way we distance ourselves into this epidemic of not being connected with people. It proposes relationality. How is its value determined through its impact on others? In UBUNTU PUNK, we want to talk about high tech, high life. We want to talk about how we are building something which focuses on compassion and reciprocity, which focuses on co-responsibility. Imagine a technology built from that assumption. I think a lot of what we’ve seen is this weird cyberpunk imagining of these shining buildings with things that do things, with no real consideration of how this impacts people outside of our bubble, and how it would be sustainable or practical for them to access those technologies. Under this philosophy, we might think towards UBUNTU PUNK.

Main Takeaways

The things I’d like you to take away are, bigger is not always better. Find the right size model that will do the task. You don’t always need the biggest one. Let’s focus on techniques that are littler and more efficient. Business models are sustainable. I think this is really important. OpenAI have another tweet from Sam Altman, where they’ve actually got a number of their plans that they’re offering, which aren’t even sustainable for their business. They’re making a loss on it already. If the people who are allegedly the best at what they do, and you’d hope they’d be the most efficient, are very unable to actually make the AI business work, we need to be very focused on how we’re making it sustainable. Because at this rate, it might just die out and not be useful to anyone.

Questions and Answers

Participant 1: I worked a little bit with a literacy group in Cameroon. They were helping to create a written language for a language that does not exist, which is purely spoken for hundreds of years. What are your thoughts in terms of using AI to help with just literacy in general? If there are opportunities for languages that are not spoken, most of the languages in Africa are not written language, they’re just spoken language. There’s no written record of anything, so you’re just training on pretty much audio and voice. There’s a lot of people on that. I just want to hear your thoughts about it.

Jade Abbott: I think because we’re English, and text is prevalent, we understand things to only exist that everything has to become text. A lot of the things that we think about at Lelapa, actually, our main technologies are not LLMs. Our main technologies are transcription and translation tools, sometimes avoiding going to text. Text is a nice, useful intermediate. It’s a lossy compression. Actually, why do we need to have things in text? Do we need to have things in text? What is the value of having things in text? Is there a speed thing? What are we optimizing for when we want to make things literate? Why are we creating written versions of languages that are primarily spoken? Really tearing apart what that means to us has been really important.

Like I said, a lot of our work really is focused on speech. We’ve seen this rise of speech in communication and teaching and things like that. For us, a challenge is like, yes, maybe we do need to use these tools to do that. We’ve come up with a number of them of like, if you create a model that is able to do that, it can spit out the text, and then maybe they can be helped to learn back. There are thousands of ways of thinking about it. I think the first challenge is, do I really need that to learn? Which parts of it do I need? Do I need the full language? Do I just need something that can do the mathematical symbols? Is that maybe the priority? That’s just a different angle on it is, do we really need written text in the way that we’re aware of it? We have digital tools, can we leapfrog that in some way?

Participant 2: You were talking about the more efficient ways of producing LLMs and the impacts of stuff, quantization and stuff, all sorts of numbers go down, and actually the output still seems pretty good. I just wonder if you could talk maybe a little bit of the experience of, in what way is it degraded? The current LLMs are so broad. Is it that these smaller ones, if you’re focused on a narrower problem domain, you won’t see a degradation, or does it decrease in breadth or sharpness?

Jade Abbott: I was particularly focused on fit for purpose. That’s the other way you can make the thing smaller, is by just making it fit for purpose. I think people keep doing lots of really interesting research studies in what the quality of these things are. I frankly don’t think we’ve got a good standard. In our organization, we have an entire team that’s just focused on quality and how we’re monitoring that over time. I don’t think we have an answer to that. For me, the big one is just make it fit for purpose. You can scale down your model much smaller.

One of the things we do is with a smaller model and very high-quality data, you can get very far. There was a paper published by Masakhane a couple years ago, it was called, A Few Thousand Sentences Can Go a Long Way. It was with regards to translation models. Translation models, you traditionally need 100,000 parallel sentences upwards. It said, but if you curate those sentences, and you make them high quality, and you make the model actually smaller, not necessarily the biggest one, one that’s fit for the size of the data, it can improve the performance. Then it becomes less about what the metrics are, it becomes more about how are we evaluating quality in terms of the use case.

Quality of the use case is, is it helping people do the thing? I don’t need something to be perfect if it helps me do the thing. I don’t need it to be perfectly transcribed as long as I can get it across. We’ve experienced this by using translation apps in our day to day. When you go to a new country and you speak, it doesn’t have to be a perfect thing to add value. I always sit there and I’m like, it’s great we’re pushing all these arbitrary benchmarks that we’ve decided as a society are the ones that decide on performance. Are they? Internally, even when they’re running them, it’s more based on their usage. They’re adapting as they go. Once again, fit for purpose. You can make it so much smaller. You can make your data smaller. You can make everything smaller. Just being like, I’m building for that. I don’t need to build for everything. In fact, what does everything mean? What does performance for everything mean? A general for whom, is always my question. Because it isn’t for everyone. It’s general, which is just the hegemonic view.

Participant 3: I particularly like the bit about data creation. I just thought that’s such a great idea. Obviously, there are some people in the world who are more focused on their finances rather than making things a bit more sustainable. I’m just wondering, how do you think we can push that idea further forward? Is it actually more financially beneficial, just based on only getting data that you need, rather than extracting things that are actually pointless, or does it need to be a more policy-driven thing?

Jade Abbott: Focusing on the, is it economically better? I have two things. At least for us, we had no choice. There was no data. There is no African data online. Even if you go find it, none of it’s digitized. Half of it’s sitting in the British Museum, which we have a project on someday, if anyone wants to come help gorillas scan books of African texts in our languages and send it back to us. We don’t have the data. For us, there is no choice. It was, we have to do this.

The thing that I find also very interesting is that what’s actually behind the scenes is that we know that they’re scraping data that they’re not meant to. We also know they’ve got deals with people. I know from being in this field, we have deals where we’re like, ok, we’ll have access to your data, and then you get reduced rates, or we’ll compensate you in some way. Often, it is monetary. I often look at the quality of what we’re getting out of different open-source models, and I can be like, why is the quality better on this one? Is it because there was some curation process, or is it because they went and made a deal with someone who’s now getting benefits in this? Really, there is a data economy happening, and no one’s talking about it, which is why no one’s reporting on what they’re training on. High suspicions that it’s already there. Number one, I think a policy push, at the end of the day, that’s one of the main reasons you can do it.

The other way is if you can make that more transparent and be like, there is a data economy. What do those models look like? For me, it’s that process of experimentation. As for us, we know we can get less high-quality data at a particular cost, and we can build self-funding models that grow the data over time. Eventually, they’re going to run out of content, so they’re going to have to do that if they want to get the models better. Generation, I think, yes, the creation of data becomes a necessity rather than just anything else. Because we’re not generating data at the rate we used to, because now it’s just being produced for us.

I always think of Stack Overflow and how no one posts on there anymore. I’m like, cool, that’s a whole bunch of problems we’re not solving. Thankfully, the computer can probably figure out the code. How many answers are not going to get answered in the long run? Policy is the way you can kick it, or advocacy is the other way you can kick it, is just being like, this is not going to work. Investors want sustainable. They don’t want the thing that’s going to burn out. Investors panic every time something like this comes out. They’re like, they’re going to regulate it. They’re already going to have to answer to that. The third one is when they just have a bunch of lawyers and they back it, I don’t know how we fight that. I think we can do it internally just by focusing on building the smaller models that work for us and not relying on them as much, I suppose.

See more presentations with transcripts